Читать книгу They Were Just Skulls - John Johnson-Allen - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 ‘We weren’t let off the hook’

ОглавлениеIf you live in, or visit, the south-east coast of England on either side of the Thames Estuary, you may see and admire Thames barges, either under way or tied up at a jetty. These days they are used as houseboats or barge yachts, or for training purposes, the latter two types often manned by a large crew, to handle the huge sails and heavy gear. There are few of these barges left.

But in 1937 when Fred Henley joined his uncle as mate – at the age of just 14 – on the barge Derby, there were huge numbers of Thames barges. At that time they were all cargo carriers, manned by a crew normally of just two, who sailed (they had no engines then) these barges up and down the Thames Estuary, and mainly along the coasts of Suffolk, Essex and Kent, and up their rivers and estuaries.

The Thames barge was the most common of all the barge types, although there were other barges of different designs which had developed in different ways to suit the area in which they sailed. Thames barges were about 80–90 feet (25–27 metres) long and they could carry about 100 tons of cargo. They were all fairly similar in their rig. They had a large mainmast, which carried the mainsail, whose upper, outer corner was supported by a long spar called the sprit, which crossed the sail diagonally and was secured to the bottom of the mast. The sail was controlled by ropes running from mast and sprit that enabled the sail to be brailed (reduced in size), or stored. Because of this, the Thames barge was often called a spritsail barge. In addition to the mainsail, a foresail was set on the forward side of the main mast. A smaller mast, known as the mizzen mast, was stepped at the stern of the barge and carried the mizzen sail. The traditional colour of all Thames barge sails was a deep reddish brown, which came from a dressing of oil and ochre; it never totally dried out, and transferred itself to the hands and clothes of the crew.

These barges had developed over a long period to suit their use, and the waters in which they sailed, and to carry the maximum load for their size. They were flat-bottomed, which enabled them to go into rivers where, when the tide went out, they could take the ground and stay upright. This flat-bottomed design also allowed them to sail, when they were without a cargo, without taking on ballast.

The design of a barge’s gear and her ability to manoeuvre under a small amount of sail, as well as full sail, had a great bearing on her ability to be handled by a very small crew. The barge skippers, like Fred’s uncle Alfred Reid, were superb seamen. They knew the rivers and the tides, and they knew their craft and what they could do.

The sailing rig, that is, mast and sprit, were made to lower so they could go under low bridges including Rochester bridge. The barges which regularly used the Medway, like the Derby and the Leslie, were so well practised in this that they could lower the gear, go through, as Fred describes, using sweeps or oars, and then raise the gear on the other side without stopping. They carried all sorts of cargoes, from corn and hay to cement and bricks. It was mainly these that the Derby and the Leslie carried, as they belonged to the fleet which, operating through subsidiaries, was owned by Associated Portland Cement, which registered over 100 barges. Both the Derby and Leslie were built in Murston in Kent which is on Milton Creek, off the River Swale. Although a small port, it was active in barge building. In 1886 there were 334 barges registered as Milton built. The biggest of the barge builders was George Smeed, who built his barges at Murston, where 79 were built. In the 1930s, when Fred joined his uncle, the Smeed yard had passed to the ownership of Associated Portland Cement. The Derby had been built in 1878 and the Leslie in 1894, both registered in Rochester. The Derby was a ‘stumpy’; this meant her mast was only tall enough to carry the mainsail and support the sprit. The Leslie was, however, fully rigged: she had a topmast which was an additional mast which projected above the mainmast so a further sail, the topsail, could be set above the mainsail. Both barges were about 80 feet long and had a beam of approximately 18 feet. As they were flat-bottomed, in order to improve their sailing abilities a lee board was fitted on either side, which would could be raised or lowered using a small winch. Another, larger, winch was used to raise the anchor. The lee boards and the anchor were all very heavy, and even with a winch to assist it was heavy work. Raising and lowering the lee boards had to be done quickly, when the barge altered course onto a different tack. It was not possible to raise the board until the sideways pressure on it came off while the barge was altering course. Once the board on one side had been lifted, then the opposite board was lowered, which also took skill as the board had to be lowered quickly, but under control.

Raising the mast on a Thames barge in 2017. Eighty years earlier on the Leslie it was done by Alfred Reid, the skipper, and Fred, the mate (Author’s collection)

The winches were heavy for an adult to operate. Fred was small in stature and at 14 the effort involved would have taxed him to the very limit. It was a hard life he was about to enter.

I was at Byron Road Elementary School. School was all right, but there were a few instances where I got the cane. When I first left school I was working in a metal factory, which I detested. I was always interested in the sea; I used to go down to Chatham and look at the ships there. There were a lot of ships laid up from the First World War. I didn’t think, as a small kid, I would join the Navy. My uncle was a barge skipper; he had the Derby and then the Leslie. His name was Alfred Reid. He asked my mum could he take me, as his mate had just retired and he couldn’t find anybody. He knew I was interested in the sea, so reluctantly my mother said yes. That’s when he was in charge of the Derby.

Most of our trade was from London Surrey Commercial Docks, loading from ships – cement, wood and stuff like that – which we would take round to Whitstable, and up the River Medway. We used to go up to Walden in Kent, which was near Maidstone. We had to lower all the gear to go under Rochester bridge, then you had big sweeps to pull yourself along.

At that stage I was 14 or 15 years old. It was a life that took strength, although I’m not very tall – only about 5 feet 6 inches. A lot of the rigging was hand-operated, although we did have a winch for the mainsail and for the lee boards. One incident we had was when we were anchored in Long Reach for the night; when it came to get the anchor up we could hardly move it. We had a hell of a job to get it up with the winch, and when it was clear of the waterline we could see we had a big cable stuck in the flukes. It was probably the telephone cable from Kent to Essex! We put a rope around the other fluke, made it fast, and then lowered the anchor so it [the cable] tipped off. We got the anchor up quite close, so we could make it fast without going over the side.

Life on board was pretty basic. There was one cabin with two bunks and a cooking stove. The heads [toilet] was a bucket up forward. We took turns to do the cooking; it wasn’t very cordon bleu – baked beans and bacon or something like that. The trips varied in length; we did one trip up to Maldon, which took about two or three days, but normally it was about one to two days on the Thames. Of course we had no engine – it was purely under sail. I took the wheel several times. Once my uncle became ill. He had stomach trouble. He curled up on the deck, and I was a bit frightened. I was steering and we were doing about 5 knots. I could see the bank coming up – we were on Gravesend Reach where it turns into Short Reach, so I had to do the turn until he came round. I had to go and fasten the foresail – when you swing over onto the new tack you have to go back and release it. The lee boards were up, so I didn’t have to do those.

I managed to get home about every one or two weeks. I liked the sea, but I couldn’t swim. I became very, very muscular at that time. I was on her for about nine months, and then I went, with my uncle, to the Leslie. We left the Derby because we went onto a full-rigged barge; the Derby was a stumpy. We picked the Leslie up in Milton Creek near Sittingbourne, which is quite near the River Swale. We were carrying the same sort of cargoes, because she belonged to the same firm. Because she was a full-rigged barge she was a bit more work, because she had a topsail – not like the Derby, which had an ordinary mainsail, with mizzen and foresail. We had to haul the topsail up by hand, so it was set all the time we were sailing. I was on her for a good year.

Fred applied to join the Navy whilst he was on the barge Leslie, at the age of 15. The standard length of service at that time was 12 years, starting on his 18th birthday. On joining, he would be attached to one of the main naval bases: Plymouth (Devonport), Portsmouth or Chatham. In Fred’s case, as he lived close to Chatham it was to that base that he was attached.

Training of boy entrants was undertaken at HMS Ganges, which took boy entrants from the Chatham area and the south-east of England. It had been established in the 19th century, initially based on retired warships moored in the River Stour, which runs between Suffolk and Essex, but in the early part of the 20th century had become a shore establishment. It was located at the end of the Shotley peninsula, on high ground overlooking the confluence of the Rivers Stour and Orwell, and Harwich harbour. Ganges had jetties on the Stour side, at which the launches that brought trainees from the railway station at Harwich, Parkeston Quay, would arrive.

Ganges had a fierce reputation for harsh training. In Hostilities Only, Brian Lavery quotes the writer and explorer Tristan Jones:

since I left Ganges I have been in many hellish places, including a couple of French Foreign Legion barracks and 15 prisons in 12 countries. None of them were nearly so menacing as HMS Ganges as a brain-twisting body-racking ground of mental bullying and physical strain.

He had been at Ganges at about the same time as Fred. The Admiralty’s description was different, noting that life compared favourably with that of any good school.

The Annexe, in which Fred was to be housed, was described as ‘depressing, ugly and utilitarian’. The uniform with which all boy entrants were issued was comprehensive and complicated. Also in Hostilities Only, Ken Kimberley noted:

two jumpers, two pairs of bell bottom trousers, two collars, two shirt fronts, one black ribbon, two pairs of socks, one pair of boots, one cap and one cap band, one oil skin, one overcoat, one pair of overalls, one housewife [husif] (a sewing kit), one lanyard and one Seaman’s Manual.

The bell bottom trousers were particularly complicated, as they had six buttons to fasten, three of which were vertical as a waistband and three horizontal as a flap to cover the waistband.

Fred joined Ganges in December 1939. Despite the comments about the harsh regime at Ganges, Fred seemed to have escaped the majority of it. Possibly two years on Thames barges may have made him tougher than some of his contemporaries, who may have come straight from school.

I got my call-up papers before the war started, but we were told we had to hang on until December because they were dealing with the reservists that had been called up. I had applied to join at the back end of 1938, when I was 15. I was given a date, when I was called up, to go to Whitehall in London with a rail warrant that they sent us, and we went to a part of the Admiralty building. There were a couple of dozen of us, shipped to Liverpool Street by lorry. We had a petty officer who came with us to Liverpool Street. He saw us onto the train at Liverpool Street, and then we were met at Harwich by a petty officer in a launch, who then took us across the river from Parkeston Quay.

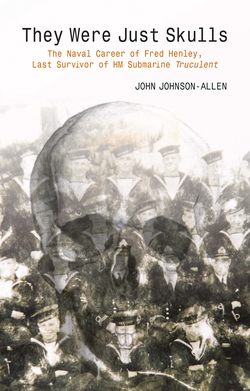

Fred’s term at HMS Ganges [photograph recovered from Truculent] (by permission F. Henley)

I was wondering what was going on. It wasn’t too official until we got there, and then it was a different story. They took us to an annexe to the main building across the road – they were Nissen huts. We trained there, drilling and being familiarised with the Navy and the regulations. We didn’t do any practical seamanship there: we spent a lot of time sewing our names into our clothing and our hammock. We got given all of our kit, kit bags and hammock – although we didn’t sleep in hammocks at Ganges; we slept in beds. We used our hammocks as bedding, as well as a blanket. They had racks to put your hammocks in.

Reveille was at 05:30, when you had a big cup of cocoa – well they called it cocoa. Then you did chores, mostly cleaning, and then you went to breakfast. After breakfast it was instruction through until lunchtime. You finished dinner, then you had an afternoon session of instruction. We had a meal about six o’clock, and then it was chores or something; we weren’t let off the hook. Pipe down was at nine o’clock.

The food was fairly good, better than the barge – it was more varied. We did some boat work at Ganges. We used to go quite a long way up the River Orwell in pulling boats –cutters – and we did some sailing in whalers, which were rigged with lugsails, which was quite similar to the way the barges were rigged. My instructor, who was a leading seaman, was an old chap from the First World War. His name was Percy Humphreys, and he found out that I knew how to sail. He was a nice, very amiable, chap, and he treated us quite well, not like the main instructor Chief Petty Officer McIntyre. He was a hard taskmaster – he could use his fists. I had a few slaps around the ears. If you made a mistake in drill he used to come up to you and then glare at you – and then bump! It wouldn’t be allowed these days. I had some home leave at Easter. I was at Ganges for about three months.

In May 1940 all boy entrant training was moved from Ganges to a new naval base, HMS St George in the Isle of Man, which had been set up at Cunningham Camp, a former holiday camp on the island. When Fred went there it would have been at the beginning of that move.

Fred’s move with the rest of his class to the Isle of Man was one of the results of the necessarily rapid expansion of the Navy with the outbreak of war.

Prior to hostilities the number of volunteers joining had increased year on year, but now many more were urgently needed. In its early estimates the Admiralty considered that it needed to expand by 75,000 men in the first stage of the war. This number was easily reached with the aid of conscription, as there was still a large number of men unemployed in 1939. This took the Navy to 310,000 men – but the early events of the naval war had generated the need for many more ships than had been anticipated. Some of these had been taken over from the French, and 50 old four-funnel destroyers had been acquired from the United States Navy. In addition, a number of cargo passenger liners from the Merchant Navy had been converted into armed merchant cruisers. So a further 40,000 men were needed to help man the extra ships.

The numbers of men that needed to be trained, therefore, escalated at a huge rate. The existing bases for the training of boys, HMS St Vincent at Portsmouth, HMS Caledonia at Rosyth and HMS Ganges, all became training bases for conscripted men, known as Hostilities Only (H.O.) ratings, and this was why the training for the boy entrants was moved to the Isle of Man.

The Navy required all boy entrants to be literate, and 9 of the 26 weeks of training were given over to normal education. At St George the teachers were former civilian schoolmasters who had been called up to serve. The standard of education there was considered to be better than was the case at Ganges. Some of the instructors for the practical subjects were retired petty officers who had returned to the Navy. Although they were out of touch with the modern Navy of the day, their knowledge was adequate for basic training for boys. Their methods of instruction varied from the authoritarian to the academic, with more of a tendency to the former.

In April 1940 I went to HMS St George on the Isle of Man. We took a bus to Ipswich and then the train all the way across to Liverpool. Then we caught the ferry to the Isle of Man, escorted by two destroyers. There must have been 300 or 400 of us who went across in that draft.

When we got the Isle of Man they split us up; some went to an old camp in Douglas but we were sent up to Onchan, a bit out of Douglas. It was a hotel called St George. There was another camp for signalmen, up at Peel. It was a lot pleasanter there. There were four to a room – at Ganges there were two or three dozen in a room. The training was more or less the same as at Ganges: seamanship and gunnery. They had an old 4-inch, a very old gun, to train on. We did more sailing; we used to go down to Douglas to the boats. We sailed straight out into the Irish Sea. Some people were seasick, although I was never seasick – and wasn’t seasick in all my time at sea. They would let us go out if it was a bit choppy, but not if it was really rough. The instructors were the same ones who came with us, including Chief Petty Officer McIntyre, and he brought his wife as well. He was a bit more amiable with his wife there. She used to come and watch whatever activity we were on; she would be in the background. I was there until October 1940.

Training was now over for Fred. He was ready to join his first ship. After his leave at home in Gillingham with his family, he went the few miles to Chatham Royal Naval Barracks. By the end of 1940 Chatham was being heavily bombed, and on 3 December the dockyard was the target, the sky over Chatham glowing red from the fires. On the 14th a land mine fell on Ordnance Street, Chatham, causing huge damage. The dockyard was always a major target; during the war it had over 1,300 air raid alerts, and 92 bombs fell on the dockyard alone. Despite this, the number of ships refitted there was about the same as the number of air raid alerts.

Fred’s draft to join HMS London came amongst all this.

After that, I had about 10 days’ leave and then reported to Chatham, where they sent us up to Borstal, the young offenders’ institution in Rochester. It was a big establishment, and they divided the place so there were prisoners one side, and we were on the other. We slept in the cells; the only difference was that the doors were open. I suppose we had the same food as the prisoners. I was there until about December, when I was drafted to HMS London.