Читать книгу They Were Just Skulls - John Johnson-Allen - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

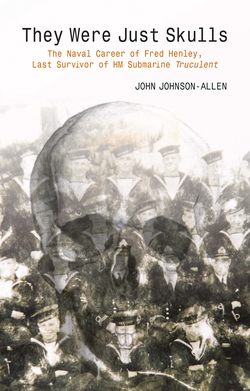

Introduction

ОглавлениеI was introduced to Fred by a mutual acquaintance in April 2017. At the time he was a very sprightly 95-year-old. I had been given some clues as to the bare outlines of his naval service. The shortest time he spent on any one ship was the two and a half months he spent on Truculent, which was to end in her tragic sinking.

He had had an early start to a seagoing life, sailing as mate at the age of only 14 on a Thames barge, skippered by his uncle.

His wartime service was remarkably eventful. As a boy seaman on HMS London, he visited Archangel, sailed on Arctic convoys and was on a boarding party to capture a German supply ship.

He followed this by three years in the Mediterranean on a motor launch, ML 463, where the small crew made the necessity to work as a team even more vital than on a bigger ship. He was involved in actions in the western Mediterranean as part of Operation Torch, the landings in North Africa. He saw the eruption of Vesuvius in 1944 whilst at Naples, and when, towards the end of the war, ML 463 was based in the eastern Mediterranean she was operating around the Greek islands as the Germans were retreating. Because of his early experience on a sailing barge, he spent some time on a captured Italian sailing vessel, sailing under the Greek flag with a Royal Naval crew.

The loss of Truculent in 1950 was a major tragedy, with only 15 survivors from the crew and the additional civilian personnel from Chatham Dockyard who had been on board as she returned from trials after her refit. In Chapters 6 and 7 the loss is discussed in detail, using the original documents from the Naval Court of Inquiry following her loss, and from the Swedish Court of Inquiry concerning the actions of Davina, the ship that hit her, quoting witnesses from both ships.

Within a handwritten Admiralty minute tucked away at the back of the file at the Royal Naval Submarine Museum archive is the following comment:

I agree with the first part of paragraph 11, i.e. that it was the initial error of altering to port that started the chain of events leading to the collision and that the correct action should have been to hold one’s course, alter to starboard or stop. There seems no escape from the fact that Truculent was to blame in this respect.

That there was an unforgivable lack of knowledge of the lights prescribed for use at night by the International Regulations for the Prevention of Collision at Sea by the officers on the bridge of the Truculent cannot be argued. All the other events of that night followed from that lack of knowledge.

I spent about eight hours with Fred, recording his memories. I have changed very little of what he said, only smoothing out the transition from the spoken word to the written. Once or twice I queried as to whether what he was saying would shock his grandchildren, although I suspect they probably already knew. He was unconcerned. All his words and reminiscences are inset.