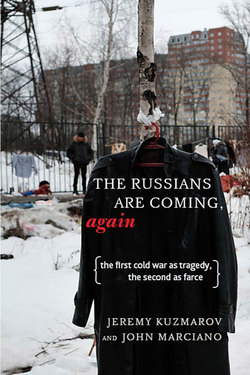

Читать книгу The Russians Are Coming, Again - John Marciano - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

“The Time You Sent Troops to Quell the Revolution”: The True Origins of the Cold War

Did we declare war upon Russia

when we took a hand in the game

I know that we hopped onto Prussia

And Austria got the same.

But still I have no recollection

Of breaking with Russia, I swear

And cannot help making objection,

To having our boys over there

What quarrel have we with that nation?

Just how did it tread on our toes?

—GEORGE SMITH, “What About Bringing Them Home,” 1919

Why are you fighting us, American? We are all brothers. We are all working men. You American boys are shedding your blood away up here in Russia and I ask you for what reason? My friends, and comrades, you should be back home for the war with Germany is over and you have no war with us. The co-workers of the world are uniting against capitalism: Why are you being kept here, can you answer that question? No. We don’t want to fight you. But we do want to fight the capitalists and your officers are capitalists.

—BOLSHEVIK ORATOR, near Kadish in northern Russia, January 1919

As a new Cold War heats up today, it is no surprise that the history of the First Cold War has been distorted to fit a triumphalist narrative about U.S. policy, its adverse consequences predominantly overlooked.1 President Barack Obama, a key architect of the Second Cold War, in his book The Audacity of Hope (2006), praised the postwar leadership of President Harry S. Truman, Secretaries of State Dean Acheson and George Marshall, and State Department diplomat George Kennan for responding to the Soviet threat and “crafting the architecture of a new postwar order that married [Woodrow] Wilson’s idealism to hard-headed realism.” This, Obama says, led to a “successful outcome to the Cold War”: an avoidance of nuclear catastrophe; the effective end of conflict between the world’s great military powers; and an “era of unprecedented economic growth at home and abroad.” While acknowledging some excesses, including the toleration and even aid to “thieves like Mobutu and Noriega so long as they opposed communism,” Obama went on to praise Ronald Reagan’s arms buildup in the 1980s when he himself came of political age, saying that when the “Berlin Wall came tumbling down, I had to give the old man his due, even if I never gave him the vote.”2

Obama’s remarks reflect a strong element of wishful thinking echoed in academic studies that blame Joseph Stalin principally for the outbreak of the Cold War and praise the visionary quality of America’s “wise men” in saving the world from Communism.3 Left out is how U.S. policymakers constantly exaggerated the Soviet threat to justify expanding a U.S. overseas network of military bases, caused serious economic problems through excessive military spending, waged violently destructive wars in Korea and Vietnam, and led the world close to the nuclear brink during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Obama and others advancing a similar worldview meanwhile neglect the real reason the Cold War started and when it actually broke out, which was at the dawn of the November 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

Showing what Wilsonian idealism was really all about, President Wilson deployed over ten thousand American troops to the European theater of the First World War, alongside British, French, Canadian, and Japanese troops, in support of White Army counterrevolutionary generals implicated in wide-scale atrocities, including pogroms against Jews. This “Midnight War” was carried out illegally, without the consent of Congress, and was opposed by the U.S. War Department and commander in Siberia, William S. Graves. He expressed “doubt if history will record in the past century a more flagrant case of flouting the well-known and approved practice in states in their international relations, and using instead of the accepted principles of international law, the principle of might makes right.”4

The atrocities associated with this war and the trampling on Soviet Russia’s sovereignty would remain seared in its people’s memory, shaping a deep sense of mistrust that carries over into the present day. For Americans, the “Midnight War” is a non-event, however, because it does not fit the dominant triumphalist narrative of the Cold War or reflect well on a liberal icon and the tradition he invented.

As historian D. F. Fleming wrote:

For the American people, the cosmic tragedy of the intervention in Russia does not exist, or it was an unimportant incident, long forgotten. But for the Soviet people and their leaders the period was a time of endless killing, of looting and raping, of plague and famine, of measureless suffering for scores of millions—an experience burned into the very soul of the nation, not to be forgotten for many generations, if ever. Also, for many years, the harsh Soviet regimentation could all be justified by fear that the Capitalist power would be back to finish the job. It is not strange that in an address in New York, September 17, 1959, Premier Khrushchev should remind us of the interventions, “the time you sent the troops to quell the revolution,” as he put it.5

These comments suggest that the U.S. invasion helped poison U.S.-Russian/Soviet relations and contributed significantly to the outbreak of Cold War hostilities. It laid the seeds, furthermore, for all the destructive policies that were to come—including executive secrecy, the eschewing of diplomacy, burning of peasant villages, and arming of violent right-wing forces—which in turn mark the Cold War as a dark chapter in our history.

DURING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, the Franklin Pierce administration sent a military delegation to assist Russia during the Crimean War, and Russia returned the favor by sending a naval fleet as a signal to the British and French to desist from their plans to intervene militarily on behalf of the Confederacy in the U.S. Civil War.6 Popular stereotypes about Russia pervaded nevertheless, exemplified in Theodore Roosevelt’s characterization of Russians as “utterly insincere and treacherous … [without] conception of the truth … and no regard for others.” He and his contemporaries feared that an independent Russia could not be counted on to acquiesce to American control in Southeast Asia and designs of opening up the fabled China market.7

The Bolshevik drive to nationalize industry and seize foreign assets was ideologically and economically anathema to the United States, which in 1917 held investments of over $658.9 million in the country, up from $26.5 million in 1913. Historian William Appleman Williams noted that almost all products of American industry were sold in Russia. Baldwin locomotives and U.S. Steel enabled the Trans-Siberian railway and Chinese eastern railways to run smoothly. International Harvester, which controlled the Russian market for agricultural machinery, even requested through the U.S. ambassador an intervention by the tsarist government to break a strike in Russia. The House of J. P. Morgan had given “great impetus to the rise of direct investments” after helping set up the American-Russian Chamber of Commerce in 1916. On the eve of the Revolution, Dean E. F. Gray of the Harvard Business School considered “Russia an inviting field for American business enterprise,” that the Bolshevik takeover threatened.8

The Russian Revolution unfolded in two phases. In February 1917, the tsar was overthrown and Aleksander Kerensky established a liberal provisional revolutionary government. It was deeply unpopular because Kerensky kept Russian forces fighting in the Great War on the side of the Allies when they had begun to mutiny, and he refused to meet the demand for land and wealth redistribution. Following a counterrevolutionary putsch by Lavr Kornilov, whom the New York Times heralded as “the strong man who would deliver Russia from her tribulations,” the Bolsheviks seized the Winter Palace in November 1917, led by Leon Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin, who envisioned the creation of a classless utopian society.9

Horrified by the Bolsheviks, American liberals, as Christopher Lasch detailed in The American Liberals and the Russian Revolution (1962), were enthusiastic about Kerensky’s bourgeois revolution because it removed a stumbling block to Russia’s effective participation in the Great War on the side of the Allies. The February revolution, Lasch notes, “purified the allied cause,” making it easier for its supporters to conceive of it as a “conflict between the principle of democracy and the principle of autocracy,” as the Springfield, Missouri Republican declared.10

To keep Russia in the war, the Wilson administration extended tens of millions in credits for armaments and military supplies to Kerensky’s government, with J. P. Morgan also raising money in direct support of Kerensky’s cause. The influential diplomat George Kennan Sr., author of an exposé of the tsarist criminal justice system that depicted Russia as an embodiment of Dante’s Inferno, lost patience with Kerensky because of his unwillingness to undertake a thorough purge of the opposition. Kennan hoped for the emergence of a strongman who would forcibly suppress every trace of radicalism in Russia. He lamented the Bolsheviks’ strong urging for peace, fearing they would use their popularity in ending the war to proceed with their “crazy plan” for “turning Russia upside down with the proletariat on top.”11

Secretary of State Robert Lansing, a corporate lawyer married to the daughter of Secretary of State John Foster (making him the uncle of John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles) was similarly skeptical of Kerensky, not because he was “incompetent, inefficient and worthless” as British General Alfred Knox considered him, or failed to “reach down roots into the life of Russia,” as Raymond Robins, director of a Red Cross mission, recognized, but because he “compromised too much with the radical element of the revolution.” Like Kennan Sr., Lansing considered Bolshevism a “despotism [born] of ignorance,” that is, of the mob, and a menace that could trigger social unrest “throughout the world.” Lansing asked: “Because wealth unavoidably gravitates toward men who are intellectually superior and more ready to grasp opportunities than their fellows, is that a reason for taking it away from them or for forcing them to divide with the improvident, the mentally inferior and the indolent?”12

Lansing’s viewpoint reflected an engrained class prejudice among America’s foreign policy elite that drove conservative, anti-radical policies. Charles S. Crane, another influential adviser to President Wilson, and who later urged FDR to support Nazi Germany as a “bulwark of Christian culture,” spoke of the “futility of revolution as a means of progressing and the fearful disaster that may overtake a state and all of its citizens if it does not progress in orderly fashion.”13

Releasing its decision to the press weeks after the fact, the Wilson administration initially justified sending troops from the European theater of the First World War into Russia as an extension of the war against Germany. Edgar Sisson, the Petrograd representative of the Committee on Public Information, a propaganda agency set up to promote U.S. involvement in the war, produced a series of sixty-eight documents purporting to prove that Lenin and Trotsky were German agents. Later, however, these were proven to have been fabrications. When the Bolsheviks withdrew from the war, the military campaigns continued with backing from prominent intellectuals, moderate labor leaders like Samuel Gompers, who considered the Bolsheviks to have “used every means to throttle freedom by joining Germany in its efforts to enslave the world,” and business executives like R. D. McCarter, president of Westinghouse and a later associate of President Herbert Hoover who considered armed intervention in Russia “absolutely necessary … as a prerequisite for building grain elevators … refrigerator plants and cars … railway improvements and new railways.”14

Raymond Robins, chairman of the Progressive Party Convention in 1916, became a dissenting voice urging accommodation alongside State Department envoys William Bullitt and William Buckler, who reported the Soviets’ willingness to compromise on foreign debt and protection of existing enterprise and to offer amnesty to Whites and cease foreign propaganda if peace were to be secured. Recognizing that “revolutions never go backward,” Robins proposed an economic program designed to tie the Soviet economy to that of the United States, persuading Lenin to exempt the International Harvester Company, Singer Sewing Machine Company, and Westinghouse Brake Company from his nationalization decree. For these efforts, he was recalled and shadowed by agents of the Bureau of Investigation (later the FBI), a victim of the mounting anti-communist hysteria of the first Red Scare.15

Robins nevertheless influenced congressional anti-imperialists such as Senators William Borah (R-ID), Robert La Follette (R-WI), and Hiram Johnson (R-CA), who wondered whether in attempting to destroy Bolshevism the Wilson administration was bent on putting “the Romanovs [back] on the throne? Do we seek a dictator for this starved land?” Johnson continued: “I warn you of the policy, which God forbid this nation should ever enter upon, of endeavoring to impose by military force upon the various peoples of the earth the kind of government we desire for them and they do not desire for themselves.”16

President Wilson had long believed in a strong executive, which he considered the only bulwark against the “clumsy misrule of Congress.”17 He was also a vigorous proponent of U.S. expansion, having previously sent forces to help suppress revolution in Mexico. At one point, he acknowledged that the October Revolution was a “desperate attempt on the part of the dispossessed to share in the bounty of industrial civilization” and that the Russian people had grown impatient with the slow pace of reform, though he fretted about the revolutionary effort to “make the ignorant and incapable mass dominant in the world.” The only remedy for “class despotism in Petrograd,” as Wilson and Lansing saw it, was for a “strong commanding personality to arise … and gather a disciplined military force [capable of] restoring order and maintaining a new government.”18 Great hope in fulfilling this role was placed with Admiral Aleksandr Vasilevich Kolchak, a famed Arctic explorer and commander of the Russian Black Sea Fleet. Kolchak was known for a rash temper that often led him “beyond the limits of the law.” James Landfield of the State Department was among those “greatly heartened” by the November 1918 coup Kolchak launched, with British backing, in Omsk, Siberia, believing that at last real military power might emerge in Russia that could “restore orderly existence.”19 Wilds P. Richardson, commander in northern Russia, claimed that “the Russian mind generally speaking [was] several hundred years behind the mind of Western Europe and the United States in the matter of free or democratic government and that [it would] take some generations to develop it.”20

Declaring himself “Supreme Ruler of Russia,” Kolchak received thousands of machine guns, hand grenades, and explosives from the Allied stock. His cause was championed by, among others, Winston Churchill, the New York Times, the U.S. consul general in Irkutsk, and J. P. Morgan.21 The Omsk group, however, represented the “minority and ancient imperialists who were obstinately impervious to the new Russia flaming in revolution against age-long abuses and tyrannies,” as a lieutenant in the 339th Infantry put it. According to General Graves, “Kolchak did not possess sufficient strength to exercise sovereign powers without the support of foreign troops.”22

The American ambassador to Japan, Rowland Morris, reported that all over Siberia under Kolchak’s rule, there was an “orgy of arrests without charges; of executions without even the pretense of a trial; and of confiscations without the color of authority. Panic and fear has seized everyone. Men support each other and live in constant terror that some spy or enemy will cry ‘Bolshevik’ and condemn them to instant death.” Among those killed were former members of the constituent assembly, and railroad workers who had struck for higher wages. In Ekaterinburg, where the Bolsheviks executed Tsar Nicholas II and his family, Kolchak allowed Cossacks to massacre at least two thousand Jews, part of a larger wave of pogroms.23

Unconcerned about these atrocities, President Wilson set up a “little war board” to expedite arms shipments to Admiral Kolchak. He provided military support without congressional sanction through Kerensky’s former ambassador to the United States, Boris Bakhmetev, who controlled over $200 million in assets. Historian Robert Maddox wrote that “by conserving and augmenting the embassy’s resources, the Wilson administration established what amounted to an independent treasury for use in Russia … [which was] immune from prying congressmen. The ambassador of the Russian people had now become the quartermaster for the Kolchak regime.”24 In short, the “Midnight War” was waged by executive power, setting an early precedent for today’s imperial presidency.

To keep the Bolsheviks at bay, the State Department established an intelligence apparatus, headed by an American businessman of Greek-Russian extraction, Xenophon Kalamitiano, which infiltrated Soviet-controlled territory and promoted anti-Bolshevik propaganda. Under future president Herbert Hoover, head of the American Relief Administration (ARA), humanitarian aid was positioned to assist the anti-Bolshevik cause.25

The intervention in Russia was formative in the development of covert action. Two major figures in the history of American intelligence, “Wild” Bill Donovan, a Wall Street lawyer and future director of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and John Foster Dulles, whose brother Allen later headed the Central Intelligence Agency, served as military intelligence officers, with Donovan undertaking undisclosed missions in Siberia. He concluded that the “time for intervention had past [as] we were a year too late,” though “we [could] prevent a shooting war [next time] if we take the initiative to win the subversive war.”26

One of Donovan’s colleagues, Major David P. Barrows, who went on to become president of the University of California, cultivated close relations with a Manchurian detachment headed by Cossack Ataman Gregori Semonoff, who according to Barrows “was capable of great severity” toward the Bolsheviks, whom he had “devoted his life to destroying.”27 A decorated veteran of the tsarist and Kerensky armies nicknamed “the Destroyer,” Semonoff allegedly set up “killing stations,” boasting that he could not sleep at night if he did not kill somebody that day. In Trans-Baikal, according to General Graves, his men shot the men, women, and children of an entire village as if they were hunting rabbits. U.S. Army intelligence estimated that Semonoff was responsible for 30,000 executions in one year, which earned him promotion by Kolchak to the rank of major general.28

Another Kolchak deputy, Ataman Ivan Kalmykoff, roamed the Amur territory robbing, burning, raping, and executing hundreds of Russian peasants without trial, including two Red Cross representatives and sixteen Austrian musicians who allegedly housed a Bolshevik one night. Lt. Col. Robert Eichelberger said Kalmykoff’s “actions would have been considered shameful in the Middle Ages.”29 Graves referred to Kalmykoff as a “notorious murderer” and “the worst scoundrel” he had ever seen. He compared him unfavorably with Semonoff since he “murdered with his own hands,” whereas Semonoff “ordered others to kill.”30 Third on the brutality scale was General S. N. Rozanoff, who would execute the male population and burn down villages that resisted Kolchak incursions.31

Congressional hearings ignored the White Terror, which General Graves predicted would “be remembered by, and recounted to, the Russian people for [the next] fifty years.” Instead, as historian Frederick Schuman summarized, they depicted “Soviet Russia as a kind of bedlam inhabited by abject slaves completely at the mercy of an organization of homicidal maniacs [the Bolsheviks] whose purpose was to destroy all traces of civilization and carry the nation back to barbarism.” Drawing from these hearings, the press became filled with screaming headlines, claiming the Bolsheviks had even nationalized women. Graves, however, wrote in his memoirs that he was “well on the side of safety” in saying that “the anti-Bolsheviks killed 100 people in Eastern Siberia to everyone killed by the Bolsheviks.”32

A Texan with experience fighting in the Philippines and with the Pershing mission in Mexico, Graves had gone into Siberia believing his mission was to uphold Soviet Russia’s neutrality and protect the Trans-Siberian railway. He became disheartened at how America’s allies applied the word Bolshevik to “most of the Russian people,” including peasants opposed to the Kolchak coup who were “kicked, beaten and murdered in cold blood by the thousands.” This damaged the prestige of the “foreigner intervening” while serving as a “great handicap to the faction the foreigner was trying to assist.”33 Turning against the war, Graves was hounded by the Bureau of Investigation as a security risk when he came back. According to historian Benson Bobrick, “in the whole sad debacle, he may have been the only honorable man.”34

Graves had conducted an investigation which found that Kolchak would force young men into the army. If any resisted, he would send troops into their village to torture men beyond military age through methods like pulling out their fingernails, knocking out their teeth, breaking their legs, and then murdering them.35 Ralph Albertson, the Young Men’s Christian Association secretary with the army in Archangel, said that wide-scale executions by Kolchak’s forces created “Bolsheviks right and left.… When night after night, the firing squad took out its batches of victims, it mattered not that no civilians were permitted on the streets as thousands of listening ears [could] hear the rat-tat-tat of the machine guns, and every victim had friends who were rapidly made enemies of the military intervention.”36

Albertson wrote that though he had heard many stories of alleged Bolshevik atrocities that told of rape, torture, and the murder of priests, the only Bolshevik atrocity about which he had any authentic information through the entire expedition was “the mutilation of the bodies of some of our men who had been killed in the early days of Ust-Padenga”—where an entire U.S. platoon was wiped out. U.S. prisoners of war were well treated and released, with the exception of two men who died in a Soviet hospital. Sgt. Glenn Leitzell described how he was allowed to walk around the nearest city dressed in a Russian overcoat and fur cap and encouraged to attend a club where he was “harangued in English on Marxist doctrine and the evils of capitalism,” and then rewarded with plates of hot soups and horsemeat steak.”37

Referring to them as “John bolo” or “bolos,” a euphemism for wild men, American and British troops pioneered the use of nerve gas designed to incapacitate and demoralize the Red Army, and, according to Albertson, “fixed all the devil traps we could think of for them when we evacuated villages.” He noted that we “shot more than thirty prisoners in our determination to punish these murderers. And when we caught the Commissioner of Borok, a sergeant tells me, we left his body in the street, stripped, with sixteen bayonet wounds.”38

According to Lt. John Cudahy, U.S. soldiers let loose their firepower upon the “massed Bolsheviks, felling them like cattle in a slaughter pen.” On the day of the First World War armistice, Toulgas, on the Northern Dvina river, where Leon Trotsky led the Bolshevik defense, was turned into a “smoking, dirty smudge upon the plain,” as Capt. Joel Moore, Lt. Harry Meade, and Lt. Lewis H. Jahns described it in an eyewitness account.

Given three hours to vacate, the authors describe a “pitiful sight” in which the inhabitants of Toulgas turned “out of the dwellings where most had spent their whole simple, not unhappy lives, their meagre possessions scattered awry on the grounds.” With their houses engulfed by roaring flames, “the women sat upon hand-fashioned crates wherein were all their most prized household goods, and abandoned themselves to a paroxysm of weeping despair, while the children shrieked stridently, victim of all the realistic horrors that only childhood can conjure.” Sad as the situation was, the authors wrote, when “we thought of the brave chaps whose lives had been taken from those flaming homes, for our casualties had been very heavy, nearly one hundred men killed and wounded, we stifled our compassion and looked on the blazing scene as a jubilant bonfire.”39

Such dehumanization in war and desire for revenge would go on to spawn the ‘atrocity producing environment” that characterized the war in Vietnam and other Cold War conflicts.40 Moore, Meade, and Jahns’s history spotlights the “enormous” and “terrific” Red Army losses under bursts of “murderous” shelling and “dreadful trench mortars” that could shower the enemy at eight hundred yards with a “new kind of hell.” The British contingent had many First World War vets who had been gassed or wounded and were prone to “homicidal excesses,” as were the Japanese.41 A Canadian platoon from rural Saskatchewan included “unpremeditated murderers who had learned well the nice lessons of war and looked upon killing as the climax of a day’s adventure.” They committed gratuitous acts with Americans such as closing a school for the storage of whiskey, and threw peasants out of their homes, looted personal property, stole rubles from dead Bolsheviks, and ransacked churches.42

British General Edmund Ironside said he was “overpowered by the smell” upon visiting the Archangel prison; suspected Bolsheviks were crowded into dank cells sometimes sixty to a room, with the windows sealed and baths closed.43 Ralph Albertson concluded that the

spoliation of scores of Russian villages and thousands of little farms and the utter disorganization of the life and industry of a great section of the country with the attendant wanderings and sufferings of thousands of peasant folk who had lost everything but life, was but the natural and necessary results of an especially weak and unsuccessful military operation such as this one was.44

In southern Soviet Russia, the British deployed tanks and bombed enemy transport vehicles, bridges, towns, and villages. For the first time, they deployed gas bombs that caused respiratory illnesses (one victim had his eyes and mouth turn yellow and then died). The British were supporting viciously anti-Semitic White Russians under the command of General Anton Denikin. Winston Churchill, then a minister in Lloyd George’s government, urged Denikin to prevent the massacre of Jews in “liberated” districts—not out of concern for the Jews but because they were powerful in England and could impinge on his political career. He stated in 1953 that the day would yet come when “it will be recognized … throughout the civilized world that the strangling of bolshevism at birth would have been an untold blessing to the human race.”45

Historian John T. Smith reports on the bombing of Grozny on February 5, 1919, with incendiaries that ignited a large fire. He later discusses the RAF’s bombing of Tsaritsyn (Stalingrad) on the Volga, which had been defended by a Soviet committee led by the future dictator Joseph Stalin and Marshal Georgy Zhukov, deputy supreme commander during the Second World War. Allegedly a British DH9 dropped a huge missile on a building where eighty Soviet commissars were meeting, all of whom were killed.46 Such incidents would remain seared in the minds of Soviet leaders, shaping a deep distrust for the West as the Cold War developed.

Coming mostly from Michigan (“Detroit’s Own”) and rural Wisconsin, American soldiers had to fight in frigid temperatures (40 below zero) without proper clothing or boots and against a motivated and disciplined enemy that adopted effective camouflages in the snow. Over four hundred “doughboys” died, hundreds more were wounded, and one committed suicide. Most U.S. forces were disdainful of Soviet society and culture. They considered Soviet Russia a “great international dump” and “land of infernal order … and national smell.” One wrote that he would “rather be quartered in hell.”47

Tommy Thompson told a reporter in the 1950s that he remembered Siberia as a cold and dirty place where he did not know whom to trust.48 Capt. Joel Moore stated that “every peasant could be a Bolshevik. Who knew? In fact, we had reason to believe that many of them were Bolshevik in sympathy.”49 Lt. Montgomery Rice pointed out that the Bolsheviks were “inspired men even if their rifles were foul with rust, their clothing worn to rags, their bodies sour with filth, or their cheeks sunken from malnutrition.”50 Fighting with U.S. munitions captured from the tsar’s armies, they adopted guerrilla methods centered on disrupting the local infrastructure and cultivating popular support in villages, from which guerrillas could carry out ambushes and sneak attacks on invading forces at night.51 According to Moore, the Bolsheviks were assisted by “a system of espionage of which we could never hope to cope.”52

“The Battle Hymn of the Republic” sung by U.S. troops, adapted to the Russian conflict, made a joke of the quagmire:

“We came from Vladivostok, to catch the Bolshevik; We chased them o’er the mountains and we chased them through the creek; We chased them every Sunday and we chased them through the week; But we couldn’t catch a gosh darn one.” The song continued: “The bullets may whistle, the cannons may roar, don’t want to go to the trenches no more. Take me over the sea, where the Bolsheviks can’t get me, Oh my, I don’t want to die, I want to go home.”53

Another poem, “In Russia’s Fields,” was modeled after the famous First World War poem “Flanders Field”:

In Russia’s fields, no poppies grow

There are no crosses row on row

To mark the places where we lie

No larks so grayly singing fly

As in the fields of Flanders.

We are the dead. Not long ago

We fought beside you in the snow

And gave our lives, and here we lie

Though scarcely knowing reason why

Like those who died in Flanders.54

At least fifty American soldiers deserted, including Anton Karachun, a coal miner originally from Minsk who had emigrated to the United States. After he deserted, he took up a post with the Red Army in Sunchon.55 A Judge Advocate General report cited by Albertson specified that an unusually large number American soldiers were convicted by court-martial of having been guilty of self-inflicted wounds.56 Lt. John Cudahy of the 339th regiment noted: “War shears from a people much that is gross in nature, as the merciless test of war exposes naked, virtues and weaknesses alike. But the American war with Russia had no idealism. It was not a war at all. It was a freebooter’s excursion, depraved and lawless. A felonious undertaking for it had not the sanction of the American people.”57

In February 1919, the British 13th Yorkshire Regiment under a Colonel Lavoi refused orders to fight, which inspired mutiny in a French company in Archangel. On March 30, I-Company in the 339th American infantry followed suit in refusing orders, asserting they had accomplished their mission defeating Germany and were by now “interfering in the affairs of the Russian people with whom we have no quarrel.” Col. George Stewart allegedly responded that he had “never been supplied with an answer as to why they were there himself, but that the reds were trying to push them into the white sea and that they were hence fighting for their lives.”58 Though apparently satisfying, this response ran counter to the lies of the Wilson administration that the United States was only in Soviet Russia for defensive purposes and to safeguard war material and property.

Peter Kropotkin, the celebrated Russian writer, told a British labor delegation that progressive elements in the “civilized nations” should “bring an end to support given to the adversaries of the revolution” and refuse to continue playing the “shameful role to which England, Prussia, Austria and Russia sank during the Russian Revolution.” Kropotkin was an anarchist opposed to the Soviet undermining of the worker and peasant councils that initially supported the revolution, but noted that “all armed intervention by a foreign power necessarily results in an increase in the dictatorial tendencies of the rulers.… The natural evils of state communism have been multiplied tenfold under the pretext that the distress of our existence is due to the intervention of foreigners.”59

In the United States, critics of the intervention were prosecuted under the Alien and Sedition Acts passed under the Wilson administration that made it a crime to “willfully utter, print, write or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous or abusive language about the U.S. form of government, constitution, military or naval force or flag.” Radical journalist John Reed and New York State Assemblyman Abraham Shiplacoff (the “Jewish Eugene V. Debs”), who said American troops were perceived by Russians as “hired murderers and Hessians,” were among those jailed. Also imprisoned were six Socialist-anarchist activists—Jacob Abrams, Jacob Schwartz, Hyman Rosansky, Samuel Lipman, Mollie Steimer, and Hyman Lachowsky—who were beaten, given long sentences, and deported for distributing antiwar leaflets condemning Wilson’s hypocrisy and urging strikes in munitions plants. The jailings and deportations were upheld in a Supreme Court ruling.60 This case shows how intervention in Soviet Russia not only helped sow conflict abroad, but also resulted in the suppression of domestic civil liberties in a pattern that would extend through the Cold War.

It is ironic that we in the United States have always been led to fear a Russian invasion when Americans were in fact the original invaders. In May 1972 on a visit to the Soviet Union promoting détente, President Richard Nixon boasted to his hosts about having never fought one another in a war, a line repeated by Ronald Reagan in his 1984 State of the Union address. A New York Times poll the next year found that only 14 percent of Americans said they were aware that in 1918 the United States had landed troops in northern and eastern Soviet Russia, a percentage probably even lower today.61

James Loewen in Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong found that none of twelve high school history textbooks he surveyed mentioned the “Midnight War.” In two cases, the U.S. troop presence in Russia was mentioned but only as part of U.S. war strategy and not as an effort to roll back the Russian Revolution. The National World War I Museum in Kansas City meanwhile has only a tiny backroom display, which claims that U.S. soldiers in Archangel “found themselves fighting the Bolshevik Red Guards as well as the anti-Bolshevists,” which is inaccurate. A separate discussion of Siberia claims that U.S. soldiers performed guard duty and protected the railways from Bolshevik forces and that they “followed Wilson’s policy of non-aggression closely, only fighting when provoked small-scale but fierce actions resulting in 170 American dead.” These comments do not properly capture the nature of the war, with no mention at all of atrocities, the soldiers’ poems, mutiny, nor General Graves’s dissent.62

Deeper public awareness of history in the United States might force us to rethink the direction of our policies and the current slide toward renewed confrontation with Russia, and could enable us to see the world from Russia’s perspective, potentially opening possibilities for engagement. During the Second World War conferences, Stalin is said to have referred to the Wilson administration’s intervention.63 His policies were not consequently based on paranoia, but a real security threat. George F. Kennan, the Father of the Containment Doctrine, was one of the few policymakers to acknowledge the importance of the “Midnight War,” though it was after he had been removed from any position of power. In 1960, Kennan wrote:

Until I read the accounts of what transpired during these episodes, I never fully realized the reasons for the contempt and resentment borne by the early Bolsheviki towards the Western powers. Never surely have countries contrived to show themselves so much at their worst as did the allies in Russia from 1917–1920. Among other things, their efforts served everywhere to compromise the enemies of the Bolsheviki and to strengthen the communists themselves [thus] aiding the Bolshevik’s progress to power. Wilson said, “I cannot but feel that Bolshevism would have burned out long ago if let alone.”64

These latter comments remain dubious. However, it is clear that after sending troops to quell the revolution, the Soviets would never again trust the United States, predominantly for good reasons, as later history would prove.