Читать книгу The Russians Are Coming, Again - John Marciano - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

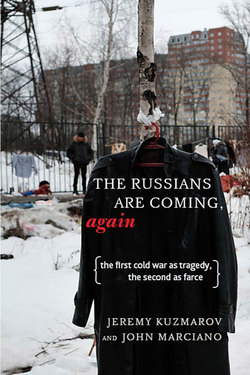

The Russians Are Coming, Again

The 1966 Academy Award–winning film The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming, directed by Norman Jewison, parodies the Cold War paranoia pervading the United States as the war in Vietnam was heating up, depicting chaos that seizes a small coastal New England town after a Soviet submarine runs aground.

Half a century later, U.S. citizens are again being warned daily of the Russian menace, with persistent accusations of Russian aggression, lies, violations of international law, and cyber-attacks on U.S. elections, as reported in leading outlets such as the New York Times and the Washington Post.

The charges are many and relentless: the Russians invaded neighboring Georgia; the Russians attempted to subvert and overthrow the Ukrainian government; the Russians shot down Malaysian Flight MH17 in July 2014 over eastern Ukraine or supported rebel forces that did so; the Russians annexed Crimea in 2014 in an aggressive move reminiscent of the Soviet Union’s postwar actions in Eastern Europe; the Russians have threatened smaller NATO nations in that region; and, most recently, the Russians engaged in cyber warfare by attempting to interfere in the U.S. presidential election and then tried to manipulate the president through connection to key figures in his inner circle.

A prime example of the new Russian hysteria comes from a 2016 report in the New York Times by national security correspondents David Sanger, Eric Schmitt, and Michael R. Gordon:

For his part, Mr. Putin is counting the days until Mr. Trump is in the Oval Office. Despite a failing economy, the Russian president has been pursuing for the past four years what most Western analysts see as a plan to reassert Russian power throughout the region. First came the annexation of Crimea and the shadow war in eastern Ukraine. Then came the deployment of nuclear-capable forces to the border of NATO countries, as Moscow, working to fracture the power structures in Germany and France and promote right-wing parties, sent a reinvigorated military force on patrol off the coasts of the Baltics and Western European nations.1

Possessing some unproven assertions masquerading as fact, such as that Putin was working to fracture the power structures in France and Germany and promote right-wing parties, the article fails to acknowledge that a verbal agreement was made in late 1990 between Mikhail Gorbachev and U.S. Secretary of State James Baker. According to the Russians, whose version is corroborated by hundreds of memos and transcripts at the George H. W. Bush Presidential Library, Baker made a pledge to Gorbachev that NATO would not expand east toward their border, in return for Russian support for German reunification.2 Since then, of course, the United States has armed and funded NATO’s eastward advance to include states that share common borders with Russia.

The United States also provocatively increased its naval presence in the Black Sea, carried out military exercises in former Warsaw Pact countries, forged ties with former Soviet republics like Azerbaijan, built oil pipelines to bypass Russia with the involvement of major Western oil companies, and covertly supported Putin’s opponents through the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) along with Islamic terrorists in Chechnya as the British had done a century and a half earlier.3

In 2014, the State Department fanned protests that led to the overthrow of Ukraine’s semi-autocratic but democratically elected pro-Russian government, prompting the Russian annexation of Crimea, which was voted on by a 95 percent majority of Crimeans. The United States then provided over a billion dollars in security assistance to a newly installed Western-friendly right-wing regime that suppressed a pro-Russian uprising in the eastern Donbass region.4

By omitting these aggressive U.S. actions, the New York Times and other media sources failed to provide proper context for many of Putin’s policies, hence furthering the impression that he alone is a major danger to world peace.

In summer 2016, the Obama administration announced the construction of a future U.S. missile defense site in Poland and the activation of a missile defense system in Romania.5 This came on top of a previously announced trillion-dollar nuclear modernization program, prompted in part by lobbying undertaken by the Bechtel Corporation, that includes the development of new nuclear-tipped weapons whose size and “smart” technology, according to a leading general, ensures that the use of nuclear arms is “no longer unthinkable.”6

Russia, not surprisingly, has viewed these policies with alarm, putting five new strategic nuclear missile regiments into service in 2016, intensifying development of long-range precision-guided weapons and a galaxy of surveillance drones, and stepping up support for the Bashar al-Assad government in Syria. Former secretary of defense William J. Perry is among those who believe that the danger of nuclear catastrophe stemming from the renewed arms race is “greater today than during the Cold War.”7

As during the original Cold War, U.S. arms manufacturers have fueled the escalation by lobbying Washington and NATO to maintain high levels of military spending, aided by hired-gun think tanks and professional experts. As retired Army General Richard Cody, a vice president at L-3 Communications, the seventh-largest U.S. defense contractor, explained to shareholders in December 2015, the industry faces a historic opportunity. Following the end of the Cold War, peace had “pretty much broken out all over the world,” with Russia in decline and NATO nations celebrating. “The Wall came down,” he said, and “all defense budgets went south.”8

Reversing this slide toward peace required the creation of new foreign enemies including the perception of a revived Russian imperialism, even though U.S. military spending, totaling $609 billion in 2016, dwarfs that of Russia, which spent $65 billion that year.9

TRAGEDY, THEN FARCE

Karl Marx famously wrote in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte that history repeats itself “first as tragedy, then as farce.”10 If the First Cold War (1917–1991) was a tragedy, the Second Cold War is playing out as Marx predicted: a farce. During the First Cold War, there was at least some semblance of legitimacy in that the Soviets had infiltrated at least one verifiable spy in the Manhattan Project (Klaus Fuchs) even if the fear of domestic subversion was ultimately grossly overblown, and some aspects of the “evil empire” lived up to this moniker. However, in the New Cold War, the Democrats, backed by most of the media have accused Donald Trump, a U.S. capitalist original and an arch-imperialist, of being a “Manchurian Candidate” surrounded by disloyal agents, which is preposterous. The agents include Trump’s wealthy son-in-law and his attorney general, who is a living monument to the Confederacy.

The charge of election interference has been accepted by most of the media even though intelligence agencies—whose legitimacy was already at a low point following the Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) debacle in Iraq—released a report so bereft of actual evidence they could only make an “assessment.” Forensic specialists working with dissenting intelligence veterans asserted that the hack on the email server of the Democratic National Committee chairman was the result of a leak by someone on the inside carried out in the eastern time zone.11

The greatest irony of the Second Cold War is surely the importance of former Communist Party USA leader Earl Browder’s grandson, William, a hedge fund manager in Russia sentenced in absentia to nine years in prison for failing to pay 552 million rubles in taxes ($16 million), in leading the lobby for economic sanctions. Browder has spread what appears to be a misleading story about a man he said was his lawyer, Sergey Magnitsky, who was actually an accountant, dying suspiciously after exposing a $230 million Russian government tax scam (the first blacklisted film of the Second Cold War, a documentary blocked from commercial distribution, has unearthed evidence that Browder made up the Magnitsky story to cover up his own orchestration of the scam).12 To make matters worse, one of the primary villains of the new Cold War, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, is an Australian national, so no one can accuse him of treason like the Rosenbergs or Alger Hiss. And there is no Whittaker Chambers who has emerged with a hidden cache of documents to aid the government’s case or savvy political opportunists like Richard Nixon to exploit the situation. All we have now is the childish Trump-Comey (former FBI director) standoff and a Senate investigation seizing on any connection between Trump supporters and the Russian government as a sign of disloyalty, which has exposed almost nothing.13

No figure has driven the new Cold War frenzy more than Russia’s ex-KGB president, Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin, who earned the ire of the American establishment with his dreams of restoring Russia’s great-power status. Putin, however, is unlikely to be hiding any gulags or show trials that could inspire moral purpose behind U.S. foreign policy at a time when the post–Second World War victory culture has receded. Furthermore, Putin is a conservative traditionalist who improved Russia’s economy from the damage done by the “Harvard Boys” and other shock therapists in the 1990s and reasserted Russian power without the bloodshed of Stalin.14 Public opprobrium may thus be hard to sustain this time around, though the scapegoating of Russia functions as a distraction for a ruling class that has otherwise lost its legitimacy. THE RUSSIANS ARE COMING, AGAIN provides a historical perspective on contemporary U.S.-Russian relations that emphasizes how the absence of historical consciousness has resulted in a repetition of past follies. The first chapter discusses the new Cold War, with a focus on the Russophobic discourse and demonization of Putin in the New York Times and its political implications. The second chapter goes back in history to uncover the forgotten U.S. invasion of Soviet Russia in 1918–1920, which was carried out without the consent of Congress, and was opposed by the military commander in Siberia, William S. Graves, who considered it a violation of Russia’s sovereignty.

The next four chapters provide a panoramic history of the Cold War, showing how it was an avoidable tragedy. Included in our discussion are the imperatives of class rule that drove the United States to expand its hegemony worldwide, the warping of the American political economy through excessive military spending, the purges and witchhunts, and the Cold War’s adverse effect on the black community and unions. The final chapter delves into the Cold War’s effect on Third World nations, which suffered from proxy wars and ill-conceived regime change operations. We also spotlight the era’s victims and dissidents, whose wisdom and courage may yet inspire a new generation of radicals.

The alarmism about Russia today has served to reinvigorate a traditional Soviet-phobia that draws on a deeper European tradition in which Russian perfidy and aggression have been used to rationalize imperialistic policies.15 Bill Browder, a key figure lobbying for the new Cold War, depicts Russia in his book Red Notice: A True Story of High-Finance, Murder and One Man’s Fight for Justice as a hopelessly corrupt, violent, and lawless country that supposedly enlightened Western entrepreneurs like himself could not save and now had to punish.16 Two generations earlier, President Harry S. Truman explained Stalin by referring to a forged document purporting to show that Russian tsar Peter the Great had developed a blueprint for conquering Europe.17 The “Father of Containment” doctrine, George F. Kennan, argued that those who wanted to extend goodwill to the Soviets had no real understanding of the malicious Russian character, which he said had been shaped by geography and a history of invasion by “Asian hordes.” According to Kennan, the “return of Stalin, a native of the Asiatic country of Georgia holding court in the barbaric splendor of the Moscow Kremlin,” confirmed that the “Bolshevik revolution had stripped Russia of its brittle veneer of European culture,” embraced since the reign of Peter the Great. “The technique of Russian diplomacy,” adopted by Stalin, “like that of the Orient … is concentrated in impressing an adversary with the terrifying strength of Russian power while keeping him uncertain and confused as to the exact channels of most of its applications.”18

This prejudicial attitude and suspicion made peaceful cooperation impossible then as now. Stalin, like Putin, did not actually act too aggressively or irrationally if we consider the history of U.S. invasion, coupled with the Soviet experience in the Second World War, and the fact that the United States virtually encircled the Soviet Union with military bases after the war. In the late 1940s, CIA director Walter Bedell Smith was so confident that the Soviets would not “undertake a deliberate military attack on … our concentrations of aircraft at Wiesbaden [Germany]” that he would “not hesitate to go there and sit on the field myself.”19

Following the 1917 Russian Revolution, U.S. congressional hearings first helped create the impression that “Soviet Russia was a kind of bedlam inhabited by abject slaves completely at the mercy of an organization of homicidal maniacs whose purpose was to destroy all traces of civilization and carry the nation back to barbarism”—a depiction that was repeated after the Second World War.20 Almost no publicity was given to atrocities committed by Admiral Kolchak, a key U.S. ally in Soviet Russia’s civil war, whose men burned villages and, according to U.S. intelligence, executed 30,000 people in one year in Siberia as part of actions that would have been considered “shameful in the Middle Ages.”21 Atrocities perpetrated by American-backed regimes like the Nazi-tainted government in Greece, Guomindang in China, or Latin American national security states were similarly sugarcoated or ignored by the “patriotic press,” whose foreign correspondents maintained symbiotic relations with the State Department and CIA.22

The media’s role in hyping the Soviet threat was epitomized by a 1951 Collier’s magazine special issue that fantasized about the U.S. overthrow of the Soviet government after the Soviets attacked U.S. cities with atomic weapons. Arthur Koestler, author of Darkness at Noon, wrote in one of the Collier’s essays that “in the Soviet slave state, human evolution” had “touched the bottom.”23 This prejudicial assessment ignored some of the major accomplishments of the Communist revolution, including its facilitation of greater economic independence, industrial growth, social equality, cultural brilliance as seen in Sergei Eisenstein’s films, Dmitri Shostakovich’s music, Boris Pasternak and Andrei Voznesensky’s poetry, and “the slave state’s” total mobilization to defeat Nazi Germany.

The Woodrow Wilson Foundation and the National Planning Association were perceptive in describing the actual threat of Communism to U.S. political and economic elites as being “the economic transformation of the communist power in ways which reduce their willingness and ability to complement the industrial economies of the West … their refusal to play the game of comparative advantage and to rely primarily on foreign investment for development.”24 General Douglas MacArthur, of all people, asserted that to sustain the Cold War the

[United States] government has kept us in a perpetual state of fear—kept us in a perpetual stampede of patriotic fervor—with the cry of a grave national emergency. Always there has been some terrible evil at home or some monstrous foreign power [Russia or China] that was going to gobble us up if we did not blindly rally behind it by furnishing the exorbitant funds demanded. Yet, in retrospect, these disasters seem never to have happened, seem never to have been quite real.25

Social conditioning combined with Russophobic prejudice thus enabled the skewed priorities in which the federal government spent an estimated $904 billion, or 57 percent of its budget, for military power from 1946 to 1967, and only $96 billion, or 6 percent, for social functions such as education, health, labor, and welfare programs. Congress rubber-stamped an arsenal of horror that included multi-megaton hydrogen bombs, intercontinental bombers with unmanned missiles, and chemical and biological weapons that had to be made operational to justify taxpayer expense.26 To contain Soviet Russian power, the U.S. further waged “limited wars” in Korea and Vietnam where it splashed oceans of napalm, defoliated the landscape, killed millions of civilians, supported drug trafficking proxies in Southeast Asia and Latin America, and unleashed chemical and likely biological warfare, while training repressive police forces in dozens of countries. The Cold War also devastated communities of leftists and activists in the United States as a result of McCarthyite witchhunts, eroding the prospects for social democracy.27

Suppressing the truth, popular commemorations of the Cold War have fixated almost exclusively on the crimes of Communism. In 1993, a bipartisan bill was passed by Congress and signed into law by Bill Clinton establishing a foundation to educate the public about the crimes of Communism and honor its victims.28 In 2007, Senator Hillary Clinton introduced legislation to establish the Cold War Medal Act to honor Cold War military veterans. Her speech referenced “our [great] victory in the Cold War” and ability to “defeat the threat from the Iron Curtain.”29 Clinton, not coincidentally, has been at the forefront promoting a confrontational policy and demonized view of Putin and Russia, and, in the style of the First Cold War, redbaited Bernie Sanders during the 2016 Democratic Party primary. She in turn is a key figure epitomizing how the distortion of public memory surrounding the first Cold War is fueling its reinvigoration today, a story this book aims to tell.