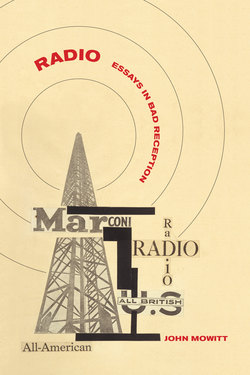

Читать книгу Radio - John Mowitt - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

On the Air

Simon Winchester, in his witty, informative, and hopelessly balanced history of the Oxford English Dictionary, archly draws attention to a detail so obvious that it might otherwise escape notice. It appears in a footnote to chapter 4, where, in commenting on the Herculean labors of Frederick Furnivall (an early editor), he points out that at a certain moment one can detect, and detect with certainty, a change in the daily paper read by Furnivall. How? All of a sudden his quotations establishing current usage of word entries shift from the Daily News to the Daily Chronicle. This anecdote, coupled with the many pages Winchester devotes to documenting the precarious history of the quotation slips gathered by the OED’s volunteer readers, casts an immediate shadow on the reliability of the dating that appears in every entry of the dictionary. Is this truly the first recorded use of a certain word, or is it the one to have survived, the one to have ended up in the right pigeonhole, as the boxes in the dictionary’s filing mechanism were called? Or is a dictionary, maybe even “the” dictionary (in the Anglophone world), structured like a language, defined, as Roman Jakobson might have put it, by the twin axes of selection and combination, where both activities, at best, cut through an unwieldy, even impossible dispersion? With such precautions taken, note that the first appearance of air used as it is used in the title of this chapter, as part of the phrase “on the air,” occurs in 1927, the year when, among other things, Heidegger’s Being and Time first appeared. According to the anonymous volunteer reader, the phrase is to be found in the British newspaper the Observer. The quotation reads: “The only New York church that is ‘on the air.’” The sense that this quotation bears witness to is one in which air is, in effect (the point, yes, of the scare quotes?), a synonym for radio, drawing attention to how in 1927 a certain metonymic perplexity characterized thought about the radiophonic medium. Was the medium of transmission part of the device, or was the device part of the medium of transmission? Put differently, where is/was the radio, and where is one when one is “on” it? Moreover, given the essayistic use of on (for example, “On Friendship”), do not these perplexities redouble when we ask where or what an essay is when it is “on” the radio, especially when—and this will be one of the core concerns in this chapter—essays, or other philosophical texts, are delivered over the radio? Is one here not faced with the anxious prepositional spiral of the on on the on? Indeed, but with what consequence?

To pursue this I concentrate here on two engagements with radio: those of Jean-Paul Sartre and Walter Benjamin. As Benjamin’s radio work was deeply entangled with his friendship with Bertolt Brecht, the latter’s writings will also be taken up. My concern will be to track how each figure thinks the relation between radio and philosophy (or perhaps thought more generally) in terms of the politics of using radio as a means by which to disseminate ideas—in effect, as a teaching machine. Two complications are stressed. First, these figures struggle instructively with the fact that philosophy is not simply radiophonic content. Instead, in ways that invite us to think twice about radio itself, Sartre and Benjamin (and Brecht for that matter) all urge us to recognize that radio is intimately caught up in the enunciation of philosophical self-reflection. Second, and this follows from the preceding, the political use of radio does not come to the medium from the outside. It is not a matter of discovering the tendency that finds expression in a given appropriation of the medium; rather, of interest here is the way the radiophonic enunciation of philosophy raises urgent questions about the very nature of the political as articulated in the cultural sphere. Not surprisingly, given the figures in play, the question of politics bears decisively on the status of Marxism, and in particular on the status of Marxism as the sublation of Western philosophy. I turn first, then, to Sartre’s Critique of Dialectical Reason, for which the fiftieth-year anniversary of publication has just been celebrated.

Although not separated out in the French text (as it is in the Sheridan translation), the discussion of the radio broadcast marks an important development in the section of the Critique devoted to the concept of “collectivities.” As such, it represents a comparatively rare engagement with what Adorno and Horkheimer had called the “culture industry” in the context of Sartre’s Herculean struggle to reconcile the account of the subject to be found in existentialism with the account of the object to be found in Marxism, the “unsurpassable philosophy” (as he called it) of his present. As the first section of the text, detached in English as Search for a Method (in French, and the rejoinder to Descartes could not be more obvious, Question de méthode), makes clear, Sartre’s ears are still ringing from Lukács’s boisterous attack on him (and Heidegger) from 1949, “Existentialism,” or, in the original German, “Zwei europaische Philosophien (Marxismus und Existentialismus),” an essay written in the wake of his return to Hungary and on the very cusp of his disillusionment with Stalinization in the emerging East Bloc. Indeed, the title of the first section of Search is a direct citation, “Marxism and Existentialism,” with the significant exception that the homonymic pun on the French et (est) provocatively, even heretically, equates Marxism with existentialism. Eager to defend existentialism from the charge of solipsism and bourgeois decadence, Sartre moves to challenge both Lukács’s sociology (if existentialism is determined by a particular class’s experience of the “collapse” of social democracy, how do we account for Jaspers’s and Heidegger’s quite different reactions to National Socialism?) and his anthropology (what precisely remains of the concept of human freedom in historical determinism?). Sartre’s ultimate concession that existentialism is to be metabolized by a thus reinvigorated (i.e., post-Stalinist) Marxism should not be understood to vitiate the importance he attaches to fleshing out his theory of the subject. Indeed, this is precisely what compels the attention to collectivities and groups where the question of the radio broadcast arises.

As if to underscore the importance of the question of collectivities, Sartre announces his turn to it thus: “We can now elucidate [éclairer] the meaning of serial structure and the possibility of applying this knowledge [connaissance] to the study of the dialectical intelligibility of the social” (Critique 269). Both serial structure and dialectical intelligibility are essential concepts of the Critique. That they are “now” in a position to be clarified marks an important, perhaps even decisive moment in the text.

Immediately prior to the discussion of the radio broadcast is Sartre’s startlingly evocative analysis of riders waiting at a bus stop in Paris. Using a distinction between “series” and “group” (as well as between praxis and the practico-inert), he demonstrates how something, some agency, external to the riders organizes them as a unity in isolation from one another: the bus, its route (indeed, urban space as a whole), and even more fundamentally the ticket that, by virtue of its articulation of an arithmetical series determining the boarding sequence (clearly a bygone procedure), is interiorized by the riders as a version of what Marx in volume 1 of Capital called the commodity, that is, as an object producing in its circulation the occulted system of their social relations. To thus restate what Marx understood by “fetishism,” Sartre invokes the concept of the series, that is, an unintelligible ordering out of which a group, through a concerted praxis of dialectical intelligibility, might emerge. Key here is the structure of seriality, the now familiar—given the enduring, if erratic, relevance of Debord and the Situationist International—motif of separation, or, more specifically, the fully interiorized sense of being alone together. This insight is crucial to Sartre’s project in the Critique because, as he says plainly at one point, he is concerned to identify how human freedom is constrained, not by the deliberate pursuit of conflicting interests, but by the interiorized forms of exteriority that render humanity, as he says in an evocative footnote, a race haunted by robots of their own making. Aware that the gathering at the bus stop lacks sufficient explanatory scope, Sartre reaches for the radio dial, or, as he says, the communication through alterity that characterizes “all mass media” (Critique 271).

Here one is brought directly to the highly charged humanistic motif of presence. This most phenomenological of concepts is deployed by Sartre to restate the relation between the bus stop and the radio in terms of direct (the bus stop) and indirect (the radio) gatherings. Both, to be sure, exhibit the structure of seriality, but in a manner clarified by an inflection of the present/absent variety. What, then, does Sartre mean by presence? He writes: “Presence will be defined as the maximum distance permitting the immediate establishment of relations of reciprocity between two individuals, given the society’s techniques and tools” (Critique 270). He offers the telephone and the two-way radio on an airplane as examples—both importantly acousmatic—as if to make sure that “distance” is not construed too narrowly. In then turning to absence—“the impossibility of individuals establishing relations of reciprocity between themselves” (270–71)—he establishes the full significance of distance. It is a way to represent the space that contains what Sartre understands, following Hegel, reciprocity. This last is more than a mere affirmation of cooperation or mutuality. It refers to the ontological work of recognition and thus undergirds what Marxism understands by “solidarity.” In Sartre’s hands reciprocity stands opposite alterity, that is, the form of social mediation premised on a passive interiorization of the “given,” the so-called nature of things. Presence names the limit of reciprocity and thus also of alterity. It is not about the face to face but about the anthro-technological conditions of a totalizing proximity. It is about the Near that may also be far, the distance that is not distant, in effect, the essence of humanity such that that essence might express itself in common with others concerned to wrest praxis from the robotic grasp of the practico-inert, or what Marx called dead labor.

How, then, does this bear on the two radios: the ground-to-air or two-way radio and the broadcast radio? The latter, by virtue of exemplifying an indirect or absent seriality, would appear to fall squarely into the experience of alterity, that is, a distance that in compromising the conditions of reciprocity would appear to fall beyond the far into the purely remote. Does this not undercut presence as the conceptual link between Heidegger and Sartre on the radio? Actually, no, but to understand why one needs to trace attentively the political dimension of Sartre’s analysis, a dimension that has direct and sustained recourse to the concept of voice (la voix).