Читать книгу Radio - John Mowitt - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAcknowledgments

Near the core of Carl Sagan’s Contact stands an episode, perhaps even an event, pertinent to the genre of which this is an example: acknowledgments. As those familiar with either the novel or the film will remember, the eponymous “contact” is discovered when the protagonist detects an electromagnetic signal repeating in what might otherwise pass as the noise of interstellar space. In time this signal is recognized as a broadcast, in fact, the televised broadcast of Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. This leads not only to the onto-theological crisis of contact itself but—and Sagan’s shrewdness shines through here—to panicked speculations regarding intentions, speculations that quickly include the conspiratorial question of hoaxes and the like. In the end, the novel itself succumbs to this hermeneutical panic, but not before reminding us that the question of where any text comes from is of fundamental, because elusive, import.

If I emphasize this instance of scientist fiction, it is because it has long been my impression that this text—Radio: Essays in Bad Reception—has been approaching for some time. If you will, it came to me (“the seeds were planted in my brain”) while I was teaching a graduate seminar in the nineties at the University of Minnesota, “Radio and the Politics of Mass Culture,” where, among other things, I was interested in crossing the analytical “pessimism” so frequently ascribed to the Frankfurt School with radio as opposed to literature, film, and television—the more typical roster of “bad objects.” Or so it seems now. At the time, the students present queried me early and often about “my objectives,” and it seems fitting here to thank them for underscoring the flawed character of the reception that I was struggling to improve in the seminar.

In a sense, this situation has repeated itself throughout the duration of this project, but in configurations as distinctive as they are worthy of grateful acknowledgment. For the sake of exposition I will distinguish among hosts, curators, and enablers, that is, colleagues and friends who have—both at length and in passing—helped me figure out what this text is trying to tell me.

Chief among the hosts who deserve acknowledgment are Joan Scott and her colleagues (the late) Clifford Geertz, Eric Maskin, and Michael Walser, who invited me to join the School of Social Science at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton for the academic year 2004–5. Joan in particular allowed me to recognize that the object of radio was transmitting to me from deep within the recesses of my earlier thinking on antidisciplinarity. She also brought me into association with an extraordinary group of scholars from whom this project has benefited in incalculable ways. I want to thank especially Caroline Arni, Mark Beissinger, Matteo Casini, Patricia Clough, Paulla Ebron, Duana Full-wiley, Bruce Grant, Sarah Igo, John Meyer, Kenda Mutongi, Helen Tilley, and Marek Wieczorek. Patricia, in particular, emerged as a consistently provocative interlocutor, and Caroline’s paleographic talents proved indispensable.

In the course of researching and writing Radio, I was invited to present it as a work in progress in various venues. I am especially grateful to the following (in the order of invitation from earliest to most recent): Negar Mottahedeh for inviting me to give one of the humanities lectures at the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University; Tina Mai Chen for including me on her Canadian Council of Areas Studies and Learned Society panel, “Culture and Globalization”; Lars Iyer and Richard Middleton at Newcastle-on-Tyne University for inviting me to participate in “Versions of the Popular;” Barbara Engh, Eric Prenowitz, and Ashley Thompson at the University of Leeds for inviting me to address the “Voice” seminar; Ika Willis at Bristol University for inviting me to inaugurate the “Beyond the Text” lecture series; Joshua Lund for including me on the Latin American Studies Association panel “After the Washington Consensus”; Meredith McGill at Rutgers for inviting me to speak at “Sound Effects”; Donna Haraway for inviting me to present my work to her colleagues (faculty and students) at the University of California, Santa Cruz; and Martin Harries for including me on the “Radio” panel at the American Comparative Literature Association’s annual meeting. As is customary, in several of these venues particular people took it upon themselves to respond or otherwise formally comment on my work, and I want to acknowledge and thank for their effort and insight Nicole Archer, Roman de la Campa, Patrick Madden, and Barry Parsons.

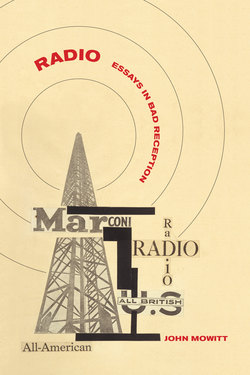

When I arrived at the Institute in September of 2004, I appeared before Joan and her colleagues with a broken left wrist from a car accident (pace Virilio). Being unable to type, that is, write (at least for me), I was hurled into the world of the archive, where I met the first in a long list of librarians, curators, and archivists without whose help this transmission would have remained unsent. I want especially to thank Momota Ganguli and Marcia Tucker, both Institute librarians; Dan Linke and Susan White, both librarians and reference specialists at the Mudd Library at Princeton University; Tara Craig, a rare books and manuscripts archivist in the Butler Library at Columbia University; Angela Carreno, a manuscript archivist at the New York Public Library; Susan Irving, a reference specialist for the John Marshall papers at the Rockefeller Foundation; Marie Walsh, a reference specialist in the Department of Sociology at the University of Birmingham; Ike Egbetola and Rod Hamilton, both archivists in the British Library for the BBC Sound Archive; Paul Spencer-Thompson, an editorial assistant at Tribune; Alena Bártová, a curator at the Prague Museum of Decorative Arts (my cover is indebted to her); and last, but certainly not least, Elissa Guralnick, who kindly shared with me her transcript of the radio program “Radio: Imaginary Visions.” With the likely exception of Elissa, I am virtually certain that none of these people will remember me, but if I have remembered them it is because they helped me tune in something faint but in the end crucial to the nebulous text I described when first contacting them. This said, now is the appropriate time to thank the late Phyllis Franklin, who, several years ago, spent a good hour with me on the phone discussing What’s the Word? That she cannot remember me is all the more reason to remember her generous spirit and commitment to the humanities “in dark times.”

Which leaves the enablers. The list is long, but it ought properly to begin with Michelle Koerner, who, over the years, has given me extensive feedback and wise counsel but who has also, when necessary, reminded me what thinking is for. Among other students (former and current), I want especially to acknowledge Ebony Adams, Nick de Villiers, Lindsey Green-Simms, Doug Julien, Andrew Knighton, Jovan Knutson, Niki Korth, Erin Labbie, Amy Levine, Roni Shapira-Ben Yoseph, Julietta Singh, Michelle Stewart (my DJ), Paige Sweet, Mousa Traoré, and Rachel “Raysh” Weiss—all of whom, in ways big and small, helped turn my receiver in the right direction. Among faculty both here and elsewhere, special, and in several cases very special, thanks are due to Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Hisham Bizri, Paul Bowman, Polly Carl, Cesare Casarino, Paula Chakravartty, Chris Chiappari, Lisa Disch, Frieda Ekotto, Barbara Engh, Jarrod Fowler, Andreas Gailus, Daniel Gifillan, Michael Hardt, Jennifer Horne, Rembert Hueser, Bob Hulot-Kentor, Qadri Ismail, Dave Jenemann, Jonathan Kahana, Doug Kahn, Michal Kobialka, Kiarina Kordela, Liz Kotz, Premesh Lalu, Richard Leppert, Silvia López, Alice Lovejoy, Julia McEvoy, Ed Miller, Andy Parker, Thomas Pepper, Victoria Pitts-Taylor, Jochen Schulte-Sasse, Adam Sitze, Ajay Skaria, Laura Smith, Richard Stamp, Jonathan Sterne, and Charlie Sugnet.

Three other more formal, but no less essential, acknowledgments are due: to Anthony Alessandrini, whose anthology, Frantz Fanon: Critical Perspecitives, provided me with an early occasion for publishing on What’s the Word?; to the University of Minnesota and specifically its College of Liberal Arts for providing research support—in various forms—for key aspects of the project; and to Mary Francis, my editor at University of California Press, who convinced me early on that she knew what this text was about and where it needed to go.

Last, I want to thank—and it always feels like such a meager gesture—my daughter Rosalind, who, when she hung stubbornly onto the weird little transistor radio that we received from our car dealer, got me thinking, and my wife, Jeanine, who in the midst of her struggle with cancer still found the energy to draw vital signs to my attention, confer about much-needed support, and be profoundly “there” in the nothing that connects everything.