Читать книгу Origami Animal Sculpture - John Szinger - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMy Origami Journey

Origami is an endlessly fascinating and rewarding art form. It combines sculpture, mathematics, and creative expression in a unique way. Although its roots and traditions go back as far as the invention of paper, origami in the twenty-first century is exploding with creativity like never before, and finally coming into its own as a legitimate sculptural art form.

I've been folding paper most of my life, starting with paper airplanes at a young age. As I matured, I devoured all the origami books at my local library. I even experimented with my own designs. Life is full of many roads, and around the year 2000 I came back to origami after a long hiatus. I started attending conventions. I met an excellent community of folders and was inspired to really work at designing my own original models.

I began creating original origami purely for personal enjoyment. I undertook the task of diagramming my models for the OrigamiUSA annual collection as a way to share with fellow folders. As my repertoire grew, the idea for a book gradually began to take shape. Along the way I've developed a folding style that works for me and seems to produce nice results. I've spent the last couple of years focused on designing new models and making lots and lots of diagrams. I'm happy that it has all come together in the form you see here.

The range of models presented here is intended for intermediate to advanced folders who are looking to tackle some deeper and more challenging models. An intermediate folder can expect to advance as he or she takes on the more complex projects. The chapters generally progress from less complex to more complex, as do the models in each chapter. A good gauge for model complexity is the size of paper that I recommend (larger generally means greater complexity). The number of steps needed to complete the project is another good way to quickly size up the relative difficulty involved in folding a given model.

ON ORIGAMI DESIGN

If you're a folder you already understand the essential appeal of origami. If you're new to origami, jump in and discover the joy of creating something out of almost nothing; just a piece of paper and some creases. This minimal starting point marvelously gives rise to almost limitless possibilities. Like music, origami has a deep basis in mathematics, particularly geometry and ratios, and from this arises higher levels of expression. Unlike most art forms, which are either additive or subtractive with their media and materials, origami is purely transformative; nothing is added or removed.

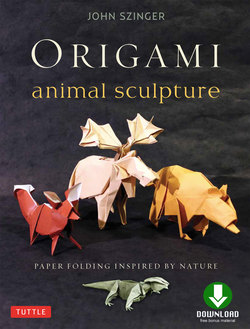

This book is mainly about animals. Although many subjects—both representational and abstract—can make good fodder for origami, animals are among the most fun to design and fold. They have broad appeal, and can be as simple or challenging as you want them to get. Even exotic animals are somehow familiar in essence, and touch on something deep within the human psyche.

My design process begins with meditation on the subject to see if I have anything to say or an approach that looks promising. Which aspects of the subject to emphasize? What should be minimized or left out entirely? Should it have claws? Does it even need legs at all, or is a mere suggestion enough? The balance between simplicity and complexity is a central concern in the creative process. While I enjoy complex models, I don't like complexity for its own sake. It's only justified if it expresses something essential. This first phase, before the folder folds anything, is perhaps the most important. Every artist will answer the question differently, and that is one of the things that makes our art compelling.

Capturing something about the posture and attitude of the subject is important. Animals are lively: they move around and do things and are not in the same position all the time. Although a finished origami sculpture is (usually) still, I strive to capture something about the subject's style of moment. Is it strong or quick or fast or slow? The stance communicates much of this. One important area to concentrate on in almost any model is the shoulders and neck; the connection between the head and the body. This often speaks much more about the subject than making detailed and anatomically correct appendages.

The level of detail and realism I'm going for informs the kind of base I need to develop. I may not always think in terms of a traditional base, but I do think in terms of what features will develop from what part of the paper and how. Developing points is one consideration, and indeed technical knowledge of how to create the points needed for legs, tentacles, claws, and antlers, etc., is essential. But that is only one aspect. Equally important is how to develop the form of the body, to control where paper is concentrated in the model, where the weight and the thickness lie. Every point generates an equal or greater amount of paper that needs to be tucked inside the model or used somehow. My tendency is to create points where needed, usually from the edges of the sheet. In fact, many of my models are just one layer of paper thick for the greater part of the body. This helps me maximize the size of the model and avoid thick masses of folds that are hard to deal with. Thickness at the edges is good for strength, and weight can be used for balance. It also allows for more freedom to sculpt the model when the finishing stage is reached.

One endlessly fascinating question in origami is symmetry. Most traditional models use 22.5-degree symmetry, which is easy to develop and fine as far as it goes. But why can't the paper also waltz? One feature of my work is the use of alternate geometries, one-sixth and one-fifth, and polar or rotational-based symmetries. Models made with these alternate geometries can have a grace that the traditional symmetries lack. Of course it's always a question of what is appropriate to the subject.

ON FOLDING

All models in this book can be folded from a single square, most from a six- or ten-inch sheet. Kami or foil will work for pretty much all of them, but for the more complex ones, or if you want to fold an exhibit-quality model, you'll want to take some care to select the right paper.

For complex models, my preference as a sculptor is towards larger sheets—12, 15, or even 19 inch. Many advanced folders prefer thin papers, but for my models that will often be too floppy. I tend to get the best results from thicker papers. Most of models in the book will work quite well folded out of papers like Canson, Wyndstone, or Tant. These papers are quite attractive and available in a variety of colors in larger sizes. As a go-to paper for advanced models, Marble Wyndstone, also known as Elephant Hide, can't be beat. Of course, it's not cheap, so I don't recommend using it for a first attempt.

Finding good two-colored paper for complex color change models can be a concern. I sometimes use scrapbook paper, although finding the right sheet for a particular subject can be hit-or-miss. I prepare my own paper from time to time. One method is to paint a sheet of paper on one side. Another is to create tissue foil. This is done by taking a piece of foil and laminating a sheet of tissue paper of the desired color to one or both sides. You can also laminate a sheet of tissue paper to one side of a paper such as Wyndstone.

Mastering a complex model is similar to mastering a complex piece of music. You may not get it perfect on the first read-through. Instead, take the opportunity to learn to model. This means working through any difficult sequences until you understand them well, and also looking for opportunities to maximize expressiveness inherent in the model. Repeatability is the important quality in the first phase, and individuality in the second. I've been folding some of these models for years and I'm still finding new ways to bring out the subject in the finishing phase.

As for understanding the diagrams, try not to worry too much if you encounter a difficult step or sequence. Understanding comes with experience. Working through a challenge makes you a better folder. Always look at the next step to see how the current fold is supposedto turn out. When you come across a complex collapsing step that involves multiple creases, it always comes down to just letting the paper do what it wants to do. In this book, the most onerous collapses are hidden once the model is finished, so just do your best to do it neatly and move on.

For complex models I oft en do a thing I call "putting it in the oven." I fold up to just before the point where the model becomes three-dimensional, and then stop to press the model flat by putting it under a pile of books overnight. This helps to really make the creases permanent so they tend not to unfold over time.

If you wish to wet-fold, save it for the final sculpting. Once you've finished the model, let it sit a day or two to see where wet-folding might be needed. I typically just wet-fold the thickest parts. A dab of water on the inner (non-visible) side of the crease will do. Once it's wet, pinch it flat with a paper clip or binder clip. Leave it dry overnight and remove the restraint the next day.

So here it is, my new collection of models. Happy folding!

JOHN SZINGER

www.zingorigami.com