Читать книгу I Have Come a Long Way - John W. de Gruchy - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

Who do I think I am?

Is it vanity to write the story of one’s life? Partly, no doubt.

But partly not. For it is also the story of millions of people, and they are my countrymen and women.

(Alan Paton)1

Isobel and I were waiting for our flight from Cape Town to London. It was January 1993. An Anglican priest and activist friend, Clive McBride, greeted us in the waiting lounge and asked where we were going.

“To Oxford for a sabbatical,” we replied, “and to explore family roots in Cornwall and on Jersey Island. And you?”

“I am going to Indonesia for the same reason,” he said to our surprise, given his surname.

The changes taking place in South Africa were sending us in opposite directions in search of our ancestral roots. For whereas our grandparents arrived in South Africa as European settlers in the nineteenth century, Clive’s maternal forbear was brought here as a slave. As a result, we were classified “white” and he “coloured” under apartheid laws. This made a huge difference to our status and prevented us from knowing much about each other’s story. Racial identity either opened doors to privilege or slammed them shut in servitude. Ours meant opportunity and possibility; that is why our grandparents came to South Africa. In doing so, they needed neither visas nor the approval of the people of the land, for the Cape colony was part of their empire. In our recent past, the question “Who do you think you are?” was a challenge to such racial arrogance. Today it also motivates a quest for an identity that might bind us together, prompting self-reflection about what I am doing here.

I cannot understand my story apart from that of the many others I have met on my journey. My life is inseparable from family, friends and fellow travellers to whom I am variously connected. For that reason their names recur in telling my story, though I cannot mention them all. I would also not be who I am if I had not been born and brought up in South Africa in the mid-twentieth century. So in telling my story I have to locate it in the country’s narrative as well. But my story also goes well beyond these shores, for it is entwined with many others in faith, action and mutual interests the world over.

Much of my life has been spent in writing, but this book is presumptuous by its very nature and different from anything I have written before. An autobiography is, after all, about the person writing it; a story constructed by the author even if based on fact. The challenge is to tell it with due humility but not false modesty, suitable honesty yet appropriate reserve, and in a way that makes it worth reading. I can only hope I have succeeded.

What has spurred me on in this quixotic task has been the fact that, for the past few years, I have often been asked to speak about my life and have been interviewed for oral history projects and the like. I have also received some unexpected honours. I presume that is because my life and experience is of some interest. But if it is, it is chiefly so because I have lived through interesting times in an interesting country, travelled to many interesting places, and been accompanied along the way by interesting folk.

The latter inevitably leads to name dropping. I make no apology for having some well-known friends and excellent mentors, and for rubbing shoulders with celebrated people. In group photographs there is always someone partly hidden in the background or sitting at the feet of others more illustrious. That is often me, but at least I am in the picture, if not the most prominent. So it gives me pleasure to acknowledge all who have been within the frame of my life, and I apologise in advance for inadvertently or out of necessity leaving some out of the narrative.

Looking back, I have often thought about my own role in the struggle against apartheid. Too often, when introduced as a speaker or being awarded some prize, I have been embarrassingly described in terms that exceed what I actually did. In honestly trying to understand who I am, it does not help to believe everything that others say about me – except acknowledging criticism and accepting affirmation where appropriate.

My children might well have asked, “What did you do in the struggle, Dad?”

Their mother provided the words for my reply:

I added my stitch or two and the tapestry

would not be diminished if I had not.

But I would. And as the work was hung

for all to see, I was glad that my few stitches

were part of the whole.2

I was not a radical activist fighting in the trenches. Compared to those who were banned, detained, tortured, exiled and murdered, most of us should remain silent. Yet I can at least say that, from the 1960s through to the end of apartheid, I added my voice in support of those who were leading the fight. I suppose I was, as has been said of me, “a leading voice in the church struggle against apartheid”. But I have no right to claim more, or look back to the past with nostalgic satisfaction. The struggle continues, and a new generation is rightly challenging the adequacy of what some of us tried to do.

Writing an autobiography is a risky undertaking, which requires self-examination filtered through hindsight; much must remain unrecorded and some purposively hidden. It is not only impossible to tell everything; it is also unwise. I owe it to family and friends to respect their privacy, revealing chiefly that which helps document my life as I have come to own it in relation to them. You can be certain that they are somewhere on most pages, even if not always mentioned. This is especially true of Isobel, to whom I have now been married for fifty-five years and whose poetry frequently finds a place in these pages.

Carl Jung described his outer life as “hollow and insubstantial”, and tells us he could only understand himself “in the light of inner happenings”.3 But there can be no separation of the inner and outer journey; they belong together, informing and feeding each other. My “soul” is who I am in my body, in relationship to others and the world in which I live with them. My greatest struggle through the years has been to ensure that the inner and outer, the emotional and the cerebral, are creatively meshed. And nothing has more traumatically galvanised me in doing so than Steve’s tragic death in 2010 – something that pervades my story as I now tell it. I would have told it differently otherwise, if I had told it at all.

I sometimes wonder how it would have been if, at some critical junctures, I had chosen differently. It is not good to brood over what might have been, though. The truth is I don’t regret the choices I made, am grateful for the many doors that opened, and even for some that slammed shut in my face. Not everything that has happened to me, however, has been the result of my choosing. I did not choose grief and deep darkness; that comes uninvited. But what I have done with such experiences has depended on choices I have made.

I have long moved away from academic writing in which the subject is “we”, a device that has enabled me to hide behind scholarly pretension. I have written many articles in scholarly journals that have conformed to such conventions, but about fifteen years ago I was encouraged to break with tradition and rid myself of the habit. Despite the dangers of egocentricity, I wrote myself into the text, blending the academic with the personal, enclosing my reflections within the narrative of my life. I began to find my voice especially in Being Human: Confessions of a Christian Humanist (2006), and most notably in Led into Mystery (2013) in which I owned my grief over the death of Steve.

Those who are interested to know more about what I personally believe as a Christian should read these books in particular. But it was, in part, the reader response to them that encouraged me to tell my story less constrained by the need for peer reviews. This led me to write two semi-autobiographical books during 2014. The first was A Theological Odyssey: My Life in Writing, published in conjunction with a conference hosted by Stellenbosch University honouring my seventy-fifth birthday. The second was Sawdust and Soul: A Conversation about Woodworking and Spirituality. Co-authored with Bill Everett, a friend of many years, the book tells my story through the lens of my working with wood.

As writing books and essays has been so much a part of my life, I cannot avoid referring to these in passing, so I suggest that those who would like more information should consult A Theological Odyssey. My life-long engagement with the legacy of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German theologian and martyr, is also a strong thread running through my story, so I cannot refrain from mentioning conferences, lectures and books related to my journey in dialogue with him. The details can be found elsewhere.

Life’s complexity refuses to be condensed into the framework that literary convention requires, but its telling needs to be anchored within a manageable timeline. I have divided my story into four chronologically determined sections. In the first part, I trace my ancestry and formative years from my birth in 1939 to my years as a young pastor in Durban, and then to my time as an ecumenical activist working for the South African Council of Churches (SACC). In the second part, I tell the story of how I became an academic at the University of Cape Town, starting in 1973. I conclude this part in 1990 when Mandela was released and South Africa emerged from the dark night of apartheid into a new day of hope and possibility. In the third part, my story is set within the context of a country in transition and a rapidly changing global society, ending with the birth of a new millennium and my formal retirement from the university in 2003. In the fourth part, I recount the last twelve years spent as a member of the Volmoed community and draw a line at the end of my seventy-fifth year.

There is a mixture of ways in which I tell my story. There are the anecdotes of age that have come to mind as I have remembered the past. I have not found the need to search for illustrations; I have more than enough stories of my own residing in what Dante called my “cargo of experience”.4 Then there are what I think of as snapshots: events that I have tried to capture as though I was still operating the Brownie camera I got as a teenager, pointing at and shooting things that were interesting and important in passing.

Insofar as an autobiography – perhaps especially one of an academic – recounts the history of ideas as they have evolved in the mind, I cannot but share reflections along the way about concerns and issues that have shaped my journey. In order to give each chapter some coherence and direction, I have highlighted these in the title and in a quotation that leads into the text. But the chapters proceed chronologically, giving an account of the passing years and using dates as signposts.

Lapse of memory is undoubtedly a problem in writing one’s autobiography at the end of a long journey. Fortunately I have considerable data at my disposal, which I have accumulated over the years and Isobel has kept detailed diaries, photo albums and journals of our travels and family life. With her scientific eye for detail, I have been kept on my toes. We also have comprehensive family archives; in fact, the De Gruchy side has a complete genealogy from the fourteenth to the present century.

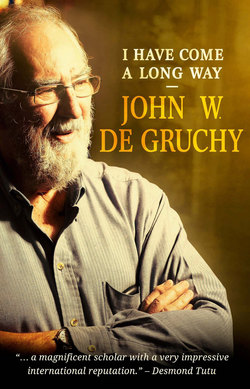

It is impossible to thank everyone by name who has helped to write my story over the past seventy-five years, among them many colleagues and students, but I can and must thank those who have helped me bring it together between the two covers of this book. I am most grateful to Rosemary Townsend and Mary Bock whose language and literary skills helped fine-tune what I had written; Susan Jordaan, the commissioning editor at Lux Verbi, who did not hesitate to support the project and guide me through it; and Isobel above all, for coming this long way with me, and making sure that I got the details right in committing the story to print. Archbishop Desmond Tutu readily agreed to write the foreword despite his many commitments, even though he has retired several times. He has been a remarkable friend over many years, and has never declined a request to commend my work. Then there is the Volmoed community, especially Bernhard and Jane Turkstra, Mike and Alyson Guy, Barry and Molly Wood, Penny Pelders and the amazing maintenance staff led by Andries Hendricks, whose care and support Isobel and I have deeply appreciated during the past twelve years.

Cape Town is very different today from when my grandfather arrived or I grew up. But for Capetonians it is always the same place, if only because Table Mountain majestically towers above it and Table Bay stretches out before it. Much of my story is based somewhere between those slopes and the sea. No matter where I have travelled or lived for a while, this is where I belong. My life has not been parochial, however, and as my story unfolds it will soon become evident that, while I am proudly South African, I am also a global citizen. I have travelled across continents, visited cities from Monrovia to Melbourne, from Beijing to Berlin, and traversed the Atlantic more times than I care to remember. I think I inherited my travelling genes from my paternal grandfather, whose story I will soon tell. But he was glad to make Cape Town his home, and it is on these shores that I know I belong, even if I go in search of my ancestors in distant places. In more ways than one, I have come a long way.

Volmoed

Easter 2015