Читать книгу I Have Come a Long Way - John W. de Gruchy - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

From whom I have sprung

The Viking name de Gruchy is already mentioned in a 9th century Norman marriage contract. Two de Gruchys were knights on the First Crusade in 1096, and another was in England in 1100 AD. When the French kings re-conquered Normandy in 1204 the de Gruchys scattered. Jean de Gruchy, the son of Hugh, a royal official, fled to Jersey, a small island off the coast of Normandy. All the de Gruchys who come from Jersey are descendants of Jean who lived at La Chasse in Trinity Parish.

(Walter J. Le Quesne and Guy M. Dixon)2

“Grouchy” is an Old Norse word which means “spear-wolf”. A ninth-century Viking contract confirms that the first Grouchys settled in Normandy (“men from the North”) in what is now France. From there, the crusader knights Nicolas and Guillaume de Grouchy rode off to participate in the Siege of Jerusalem in 1099. My father always wore a gold signet ring with their coat of arms engraved on it. Both my sister and I received such rings on our twenty-first birthdays, as was then the custom in our extended family. I still have the metal stamp used for this purpose.

There is a hamlet in Normandy named Gruchy. It is portrayed in paintings by the impressionist Millet. There is also a De Gruchy chateau nearby, which briefly appeared in the film The Da Vinci Code. But by the end of the thirteenth century, long before either the hamlet or chateau existed, our branch of the family had settled in Trinity Parish on Jersey Island, eleven kilometres off the coast of France. There they dropped the “o” in Grouchy to distinguish themselves from their mainland relations.

In the documents of the Jersey Assizes for 1299, we are told that Jean de Barentin was accused of beating Richard, son of the priest De Gruchy. This is the first mention of a small handful of priests in our family tree, which includes many more soldiers and sailors.

In Trinity churchyard there are dozens of De Gruchy tombstones, many bearing the name Jean or John. I am related to them all, even if only distantly. The original Jean was the son of Hugh, a Norman nobleman, who fled to Jersey at the end of the thirteenth century when the Frankish kings invaded the territory. The control of Jersey fluctuated between the French and the English as fortunes in war waxed and waned during the Middle Ages. But by the end of the fourteenth century, Jersey was finally brought under the reign of the English monarch, and remains so to this day. From then on, it has been governed by its own parliament or states and by the councils of the twelve parishes into which it is divided. At the time of the Reformation, the island’s allegiance switched from Rome to Canterbury.

My branch of the De Gruchy clan starts with Jean’s descendant Robin (c. 1362), who lived at La Chasse on La Profonde Rue in Trinity Parish. The farmhouse still stands, now much enlarged and no longer in the family. It was there, following the custom of their cousins in Normandy, that some of the family dropped the “de”. Our branch kept it, but our most illustrious ancestor on the mainland, Marshall Emmanuel de Grouchy, dropped the “de” after the French Revolution, but kept the “o”.

My father was the first to introduce me to Emmanuel Grouchy and gave me his portrait, which still hangs in our house. Historians blame him for losing the Battle of Waterloo. The truth is more complex, but if he had not arrived too late on the battlefield to save the day for France, the Cape of Good Hope might not have become a British colony, my grandparents would not have settled there, and I would not exist.

Emmanuel’s sister, Sophie, was absent from the family story as told to me. She was a celebrated poet and painter, whose Parisian salon attracted distinguished Enlightenment thinkers. Both siblings miraculously survived the French Revolution and lived long lives.

Emmanuel visited Jersey in 1836, when he acknowledged all the descendants of Jean as his relatives, irrespective of how they spelt their name. My great-grandfather Jean, who was sixteen at the time, must surely have seen the distinguished visitor.

Jean became a farmer and married Caroline de Quetteville in May 1842, and ten years later my grandfather Frederic Abram was born on 27 August 1852. Like all Jersey school children, he spoke French, English and Norman, but his formal education went no further than primary school. At thirteen he bade farewell to his parents and left Jersey to go to sea. There was no future for him in milking Jersey cows, growing Jersey royal potatoes, or building sailing ships at one of the island’s harbours, even though there were several shipbuilders with the name De Gruchy.

Records in the Jersey Maritime Museum document my grandfather’s early years as a sailor. But the story goes blank around the 1870s when he sailed out of Southampton rather than Jersey’s chief port, St. Helier. Sometime during the late 1880s he became the captain of a tea-trading clipper, which regularly sailed around the Cape to China. His days as a seafarer came to a dramatic end in 1883, however, as recounted in our family records:

His clipper Velocity and two other vessels were sunk during a tropical storm … Frédéric and crew took to lifeboats in the turbulent sea. To add to their plight, after the storm abated they were pursued by Chinese pirates for two days and nights. Fortunately during the third night the pirates went ahead of their lifeboat and de Gruchy, by changing direction, was able to elude them. Frédéric, with 14 sailors aboard, spent a total of nine days short of food and drinking water, before being sighted and rescued by a passing ship bound for New Zealand.3

My grandfather continued on the ship when it began its return journey to England, but disembarked in Cape Town. On the Sunday after his arrival, he attended worship at the Metropolitan Methodist Church in Greenmarket Square, where he met Mary Irish, a striking young woman who had recently arrived from England. Within a few weeks they were engaged, and were married in the same church on 18 December 1883.

Mary was born in March 1862 in Climping, Sussex, a hamlet on the Duke of Norfolk’s Arundel estate where her grandfather was bailiff. Her mother died when she was young, and there is no reference to her father in the baptismal register of the parish church in Climping; so she was brought up by her grandparents, kept their name, and her paternity was wrapped in secrecy. When she turned twenty-one, she was sent to the Cape Colony in the care of the Garlick family, friends of the Norfolks’, and wealthy shop owners in Cape Town. There exists an intriguing story that Mary received a diamond ring, sent to her from England, on each of her birthdays for several years thereafter. While the story cannot be verified, my mother believed it was true. If it was, then my paternal grandmother might well have been an illegitimate daughter of the Duke of Norfolk. For who else in the county could have afforded such a ring, and would have reason to keep the scandal a secret? It would also explain why my grandmother was sent to the colonies in the custody of the Garlicks.

Frederic Abram and Mary had nine children, of which my father, Harold, born in November 1902, was the second youngest. He and his siblings grew up in Cape Town in the Seaman’s Home on Dock Road, of which my grandfather was the director. I remember seeing it years later near the grand old Alhambra cinema, but both buildings were demolished when the Foreshore was redeveloped. Some old photographs of the waterfront and the pier in front of the Seaman’s Home show young children playing on the beach among the rowing boats. I can imagine my father being one of them.

My grandmother Mary died in 1927, twelve years before I was born, but I was told that I had met my grandfather when I was three. I have very vague memories of that occasion, but I know his bearded face from family photographs. I also remember visiting their graves with my parents in Woltemade Cemetery outside Cape Town once long ago; but I have never returned and wonder whether anyone now knows where they are located. How different their final resting place is to Trinity Parish cemetery on Jersey Island.

My father, Harold, went to the South African College (SACS) Junior and High Schools, as did some of my uncles and male cousins. After matriculation, Harold studied at the Technical College, and then became a telephone technician working for the government. He became an expert in setting up communications networks, and later pioneered the first telephone connection between South Africa and the United States. I was at the Cape Town telephone exchange on the night the first phone call was made between the two countries. But that was still some years away.

In his early twenties, Harold was transferred to Port Elizabeth where he met my mother, Mabel, the daughter of Herbert and Lily Hurd, both devout Methodists. Herbert came from London, and Lily’s parents had come to Port Elizabeth from Hull in Yorkshire. They were married in the St. John’s Methodist Church in Havelock Street in November 1896. Within ten years they had seven children, of whom my mother was the third eldest. They lived in Walmer, then a town separate from Port Elizabeth, in a rambling Victorian house I remember well.

By all accounts my grandparents Hurd were down-to-earth, generous people. On occasion they entertained visiting royalty when, during the First World War, Herbert became the mayor of Walmer. He was also the founder of the Methodist Church in Walmer. Much later, one of the high schools in Port Elizabeth was named after him.

Lily, a formidable, small woman who drove an Oldsmobile into her late eighties and sometimes drove the fear of hell into me in doing so, was also a founder of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. I really liked her.

My mother, Mabel, was born in 1900. She often told me that at that time there were no motor cars in Port Elizabeth, the Anglo-Boer War was in its second year, Queen Victoria was on the throne, there was no South Africa, and the Wright brothers had yet to fly the first aeroplane. Mabel had the honour of switching on the electricity when it finally reached Walmer, but she had little schooling or opportunities to develop her innate abilities. Instead she helped bring up her siblings and served as a nurse aid during the great flu epidemic.

When Harold came courting, Mabel’s parents insisted that they could not marry until he had sufficient income and a house. So he set to, built a house in Walmer, and made all the furniture for it, too. I still have some of the tools he used for this task.

Harold and Mabel were married in St. John’s Methodist Church on 2 August 1928. Four years later my sister, Rozelle, was born. She was named after a small fishing village in Trinity Parish, Jersey.

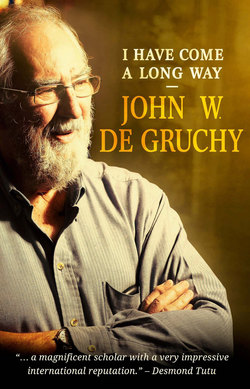

In 1938 Harold was transferred to Pretoria, where I was born on 18 March 1939. My names, given at birth, were Cedric Walter, but shortly before my baptism they were changed. I only discovered this later when I got married and my parents sent me my birth certificate, accompanied by other documents that registered the change to John Wesley. The reasons for the change are a little unclear, but it seems Cedric Walter was not a name my Hurd grandparents thought I should be burdened with. And so I was baptised John Wesley in the Hatfield Methodist Church in Pretoria on 9 April 1939. Later in life, in order to avoid denominational confusion, I began to refer to myself as John W. de Gruchy – something that our son Steve would poke fun at, especially when George W. Bush was president of the United States.

By the time I was born, my parents were already touching forty and Rozelle was six years old. Her relationship with my parents was firmly established. I was a laatlammetjie (late lamb) as the Afrikaans has it – an unexpected arrival, if not a mistake. But I had no intention of taking the backseat. On the contrary, my earliest memory is of me, probably aged three, wandering away from our house in Hatfield and ending up on the railway station nearby, watching the trains go by. My mother was understandably frantic, but she found me talking happily to a stranger.

In 1942 my father was transferred back to Cape Town. He had not been called up for overseas service in the army, because his communications job was deemed essential for homeland security. So we all caught the train to the Mother City, and it was there that I grew up.

My life would have turned out very differently if we had stayed in Pretoria and I was known as Cedric Walter.