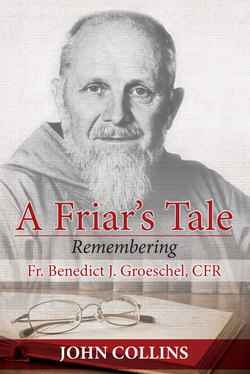

Читать книгу A Friar's Tale - John Collins - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

Looking at the Sunset

September 2012

The Tale As Father Told It

I am in a hospital with frustratingly little to do. Apparently I’ve had an infection for quite a while, but somehow failed to notice it. Despite my lack of awareness, the bacteria that have been using my body as a playground for weeks have done their work and I’m flat on my back. Antibiotics drip into my veins from a little plastic bag which is attached to a device that beeps annoyingly from time to time. I don’t know what the beeps mean, and I must confess that I don’t really care. Fr. Fidelis, one of our best young friars, is with me almost all the time, and I leave such things to him. He takes excellent care of me; in fact, his care is almost too good. Despite my best intentions, I think I am too demanding, and I fear I am exhausting him. He is very dedicated, a fine young man—a fine young priest. I hope I was half as good a friar and a priest when I was his age.

Yesterday I had a skin graft to my knee, which I injured in a fall some weeks ago. The knee, incidentally, was the port of entry for the bacteria, and it is still sore. As a result of the surgery, Fr. Fidelis and all my visitors, as well as the nurses and doctors, must wear special sterile gowns when they come near me. All the gowns are yellow, and I must say they’re rather cheerful looking. Whether the purpose of the gowns is to keep my germs from them or theirs from me is still unclear to me. They all seem to be doing well, so I assume I have infected nobody. I’m glad; I would not like to be known as the “typhoid friar.”

My room is on the fifth floor, facing west. This is a stroke of very good luck, because it lets me watch the sunset every day. I have learned, by the way, that the sunset is something you can look forward to when you have nothing to do and are too weak to do it even if you did have something to do. It is September and the weather is very clear, so the sunsets are beautiful and brilliant and, I find, very consoling. I am beginning to see them as a gift and also am beginning to realize that I have been ignoring this gift for decades. Perhaps I have ignored much that is important. I pray that I have not.

Tonight the sky is blazing red, but right now the red is beginning to give way to darkness. The light will last only a short time longer, but it is intensely lovely. As I let myself become engrossed in the fiery sky—in God’s secret gift to me—I am able to forget about being in a hospital room, about the pain in my knee, about the dripping of antibiotics, about many things that have come to burden me. I permit my mind to drift, knowing what will happen. These days my thoughts turn to the past, which is rather odd for me. During most of my nearly eighty years I have faced the future—run toward it. But lately that’s changed, and I now take a kind of pleasant refuge in the past, in thoughts of my childhood and my life as a young friar—in thoughts of a time that I believe was better for us all. Memories of people I once knew but who have left this earth long ago come to me in no particular order. These people are still very real to me, and I feel as if I will soon be in their presence again. I look forward to that; the thought is a source of joy.

Scenes from my very early life fill my mind, and they come as welcome guests. The feel and sounds and smells of our home in Jersey City—a house I haven’t entered in decades—are real to me again, as is the sound of my mother’s voice, the taste of her cooking, the touch of her soft hand. These memories are another of God’s secret gifts to me in my old age. When I am immersed in them I become free like the child I once was, rather than the old and crippled man I have become. “I dwell in possibility,” wrote Emily Dickinson over a century ago, and I always thought that she must have been thinking of a child. Like all children, I once dwelled in a special kind of possibility. For a child who has not yet been hurt by the world, as we all must eventually be, everything is bright and filled with unending wonder, limitless possibility.

It seems that God has given me the ability to dwell in possibility again, to return to those days long gone. As the sunset fades I become five years old, a little boy with his dad. My father is tall and strong, and I am absolutely confident that he can do anything. I am fiercely proud of him and hope that one day I will be just like him. He is an engineer and leaves our home every day to build buildings in other places, places that seem far away and mysterious to me. We are walking, father and son, and this walking is becoming difficult for me. My father’s legs are too long, and I can’t keep up. We are going somewhere important, and we must not be late, so I do my best. I am almost running, but I still fall behind. I feel that I am failing, but my wonderful father does not let me fail; he swoops down like a big, strong bird and in an instant I am held high in his arms. He doesn’t even break his stride to pick me up, and he carries me easily through the crowded streets. He runs up the steps of Corpus Christi Church in Hasbrouck Heights, New Jersey, as if I weigh nothing. Just before we go in, as he pulls the hat off his head, he reminds me to be good, not to speak, to pay attention, to pray to Jesus. He calls me “Peter,” as does everyone in my family, everyone I know. I was just Peter then; Benedict Joseph did not yet exist. We arrive just in time for Mass; my father carries me into a pew and deposits me on the seat.

I still remember the name of the priest. It was Fr. Fitzpatrick, and I tried to pay attention, to understand what this man in his golden vestments was doing at the marble altar. I couldn’t, for he spoke a strange language and did many strange things. In fact, at times it seemed as if he wasn’t doing much at all. But I knew differently because my father and my mother had told me that something wonderful happened when priests like Fr. Fitzpatrick were at the altar. They told me that Jesus was also there, that He comes to be with us because He loves us.

My attention wandered from Fr. Fitzpatrick and became fixed on the tabernacle—although I don’t think I knew that word then. It was a gleaming gold box at the center of the altar, and I knew it was very important because my father had told me so. He told me that in this tabernacle dwells Jesus himself. I tried to understand how this could be so, but I couldn’t—the box looked too small and not at all like a home. But I knew my father would never lie to me, and so I believed. Mostly during the Mass the tabernacle remained closed. But occasionally Fr. Fitzpatrick opened it, and each time he did I strained, trying to make myself tall enough to get a good look at what was inside. I could never quite manage it, and that was frustrating because I wanted very much to see Jesus’ house.

I thought very hard, trying to understand how Jesus could be in this box. I couldn’t figure it out. The best I could do was to think of my last visit to my cousin Julie’s home. She was a couple of years older than I, and she had a dollhouse. It was fitted out with a kitchen, a living room, a dining room, and a couple of bedrooms. Could it be that inside the tabernacle Jesus was living in something like that? To my five-year-old mind it seemed almost reasonable, and I began to wonder if Jesus had a bed in there, or a lamp. Did He even need a lamp? I was dying to know these things and so much more. I craved a glance inside the tabernacle. I was sure that if I could see inside even for an instant all my theological questions would be answered. I believed that if I could just be tall enough I would see the Jesus to whom I prayed every night. I was nowhere near tall enough, and I went home unsatisfied. But my desire to see Jesus remained with me for the whole day, and it even came back over and over again in the days that followed. It returned intensely every time my parents took me to Mass, until finally it became something that simply would not leave.

Perhaps this was a beginning.