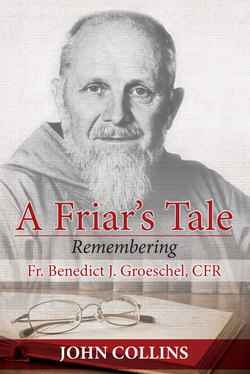

Читать книгу A Friar's Tale - John Collins - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter III

A Difference in Taste

The Tales Father Wasn’t Given the Time to Tell

Peter Groeschel’s future was much discussed among his friends as their high school years drew to a close. Nobody who knew him doubted for a moment that the priesthood was his eventual destination, but many people wondered about, and were even perplexed about, the route he would take to get there. Apparently, he was rather closedmouthed about it, offering few if any real clues; and so speculation at Immaculate Conception High School was rampant. Some claimed his intellectual acumen made it obvious that he would find his eventual home among the Jesuits. Others believed that his talents as a public speaker and his attachment to the Dominican Sisters of Caldwell made it a foregone conclusion that he would join the Order of Preachers. Of course, he entered neither community, but apparently he gave at least some consideration to each.

Concerning the Dominicans, N. John Hall wrote that the young Pete Groeschel was seriously considering becoming a member of the Third Order of St. Dominic while still in high school; that fact certainly can be considered a clue as to the way Pete’s mind was working at the time. Hall also wrote that Pete “lost his interest in the Dominicans when in his senior year he went to see the Dominican Fathers read the Holy Office in a New York City priory. The fathers seemed bored, inattentive, and one of them swatted a fly. Pete, disgusted with the Dominicans, looked around for what he thought was the strictest, most rigorous of the active orders, and settled on the Capuchin Franciscans.”3

It is very probable that Pete Groeschel gave at least some real thought to joining the Order of Preachers, if for no other reason than the one already stated: he had a warm relationship with the Dominican Sisters of Caldwell and was very impressed by them. Marjule once commented that her brother and the superior of that community, Mother Dolorita, were alike in some ways and got along well. Surely those sisters would not have hesitated to suggest their own order to a boy who was considering the priesthood and religious life, especially a boy who showed as much promise as Pete Groeschel did.

Whether the Dominican Fathers’ lack of attention at prayer (or the fact that one of them swatted a fly during it) was the deciding factor in sending Pete into the arms of the Capuchins seems a bit difficult to believe, but is impossible to know. What is possible to know, however, is that Pete’s interest in the Capuchins predated both his senior year in high school, as well as that disappointing visit to a Dominican priory. It is also possible to know that a profound desire to serve the poor lay at the heart of his religious vocation from a very early age. So it is not altogether unexpected that the Capuchins, rather than the Dominicans or any other order, would have appealed to him as he contemplated his future.

By the age of sixteen it seems clear that Pete was already focusing on the Capuchins—even though he had never met or even seen one. In fact, by that point it is likely he was becoming rather determined to cast his lot with them, as the following piece, which was one of the last things he ever wrote, shows.

The Tale As Father Told It

As I work on this little memoir, I discover some odd and interesting things. One of them is that I am able to summon up memories of events and people I haven’t thought about in many years with almost startling clarity. That’s surprising to me, because the recollection of this morning’s breakfast is vague, indeed; and, let me tell you, last night’s dinner has long ago been consigned to the realm of total oblivion. Memories from the distant past, however, seem to be like snapshots in an old, dust-covered album that I haven’t opened in ages. I expect the pictures in it to be dim, faded, and perhaps even unrecognizable. But as soon as I open the book, the past becomes present once again in all its vivid colors and details. Such things remind me of how very wrong we are to think of the past as being over and done with. It is really something that we carry with us at every moment, as an ever-present companion along the way—as an intimate part of us. It is the lens through which we view and make sense of the present. Too often we take memory for granted, as if it were an old file cabinet sitting in the corner of the room. But we should not. I find I forget many things these days, and I won’t say that’s not frightening. At the age of eighty I see that old file cabinet as a treasure, as one of God’s most wonderful gifts to us, and I take pleasure—real delight—in exploring it while I’m still able.

I once attended a memorial service for a non-Catholic friend. Sadly, the man who delivered the eulogy did not believe in life after death in any way. Yet he spoke of “the resurrecting gift of memory.” This is a startling way to put it, so startling that I recall that phrase and nothing else from the eulogy. I have come to understand that those few words contain real truth and real beauty, and perhaps even some unwitting theological insight. I make much use of God’s “resurrecting gift of memory” these days. This little book allows me to do so; it has given me the opportunity to make many moments in my past present to me once again, to make them so real I can almost touch them.

Today an image from the past has leapt into my mind with unexpected vibrancy, as sharp and clear as if it were an actual photograph. It is of my father and me when I was nearly seventeen. In this remembered snapshot I am wearing my best clothes—the same ones that I wear to Mass on Sunday—and my father is wearing a suit as well. His hat is in his hand. We are standing in front of the friary at Mount Carmel Church in Orange, New Jersey. I remember—I can almost see—that my hair is especially carefully combed. That image makes me smile a little, for it sparks another recollection, one of me earlier that day trying to look as serious and mature as possible. As part of my effort to achieve this goal I labored very diligently to get my cowlicks under strict control (anyone who knows me can attest that God has completely spared me this problem in recent decades).

As I think of myself on that day I can almost see or even feel my own eagerness and nervous anticipation, for my father and I had come to this church and this friary for a very important reason. I was to meet a Capuchin friar for the first time, and I was to discuss with him the possibility of my entering his order. As I remember myself standing in front of that friary, I know I thought I looked calm and in control. But even from this great distance I can see that was not the case at all.

The end of high school was in sight, and to my sixteen-year-old mind, that meant that the time for decisions could no longer be postponed. The moment to commit to a course of action had come. So I had searched out the Capuchin church closest to my home and made an appointment. I was growing more and more eager for this next step, and I desperately wanted it to be toward the Capuchins. If you had asked me as I stood waiting in front of that friary why I wanted this, I probably would have given you some sort of reasonably coherent answer. I’m sure I would have told you that I wanted to be of service to the poor, which was the type of work at which the Capuchins excelled.

I probably would have spoken about Padre Pio, the great Capuchin stigmatic, who had become well-known in the Catholic world after the war. He was a charismatic figure to me back then. In fact he seemed larger than life, an almost medieval saint who stood in bold defiance of many of the ideas of the secular world. But if truth be told, I didn’t really know why. It was just a vague but persistent feeling, a yearning. Yet, after all these years, I still know that it was exactly the right thing for me to do. I have no doubt that it was the step God wanted me to take; it was the direction in which He had been gently prodding me for years.

Many thoughts flow through my mind as I remember that long, empty moment before the door opened and my father and I walked into the friary. I have to admit that I recall being aware that my father was disappointed—albeit very mildly so. Although he never said anything to indicate that fact or even to hint at it, I was aware that becoming a follower of St. Francis is not exactly what he would have chosen for me if he could have done the choosing. He actually had his sights set on the Jesuits for his son. Like so many people back then, he greatly admired them. He spoke of the Jesuits in glowing tones, telling me of their greatness, their intellectual acumen, their uniqueness among the orders of the Church, their devotion to the pope. And I have to admit I was impressed by the Society of Jesus.

Several times I even gave serious thought to following my father’s advice. Yet, even though I wanted to please him and make him proud of me, I simply could not do it. I really did admire the Jesuits, and over the years I have been blessed with wonderful Jesuit friends, such as Fr. John Hardon and Avery Cardinal Dulles. But I did not feel drawn toward the Jesuits when I was sixteen nor did I at any other point in my life. The Capuchins, on the other hand, were like some unseen star that exerted a powerful gravitational pull on me. I believed that it was simply my destiny to enter their orbit. I don’t know why, but I did. I know my father accepted that, and I am still grateful to him for his wisdom and love for me, for it took both of those things for him to let me take the path that I believed God had chosen for me.

The door finally opened, and there he was: the first Capuchin I had ever seen. He greeted us warmly but rather formally. That didn’t matter because I barely heard his words. I was far too busy taking inventory of his beard and his habit, the cord around his waist and his rosary. In fact, I think I was trying to commit them to memory. He looked just like the pictures I had seen in books and Catholic magazines, and for some odd reason this pleased me immensely. I guess I thought it proved that we had found the Real McCoy. Maybe I thought it meant I was off to a brilliant start. As we entered, I was struck by the simplicity of the friary. It seemed to me to show very clearly that those who lived in it had no great love for worldly things, no attachment to luxury. On the way home that day I learned that what I saw as simplicity my father had seen as seediness. Each to his own!

I noted every detail: the San Damiano cross on the wall; the small, unobtrusive statue of St. Francis; the picture of St. Clare on a plain wooden table. Yes, I thought, this was exactly the right place. This is going to work out well—perfectly. I was very excited, for I was certain my life as a Capuchin was about to start. There would be no turning back now. My journey into holiness had begun in earnest.

But, in case you don’t know it, God has a sense of humor, one He likes to display at odd moments. Perhaps He especially likes to display it when people (even young people) are taking themselves just a bit too seriously. In other words, things turned out very differently that day from what I expected, so differently that I find myself chuckling as I remember what happened. My father and I were led to a little room that was set aside for interview purposes.

The friar who spoke with me was kindly, but after a short talk about the Capuchin life he started to approach things from an angle that absolutely mystified me. At one point he stroked his beard and looked long and hard at a piece of paper on which was written, among other things, my name. “Groeschel,” he finally said, after what seemed to be a period of inexplicable and rather inappropriately timed meditation. He then looked up at me expectantly. “Yes,” I answered, realizing that some kind of response was needed. “Groeschel,” he repeated more softly, this time while shaking his head almost (but not quite) imperceptibly. He seemed to intone rather than merely say my name, and I realized he had the ability to make it sound like it was comprised of much more than just two short syllables. In fact, he seemed able to make it go on forever.

“This is a German name?” he half asked and half stated. “Alsatian,” my slightly indignant father corrected. The friar smiled apologetically at my dad and then turned to me again. “Do you like spaghetti?” he inquired out of the blue. Was this a trick question? I stared at him blankly for what was probably too long a time. “Ah … no, not really,” I finally responded. He pursed his lips and nodded gravely. “Ravioli?” he asked, making the word sound round and full of vowels. “I … I don’t think so,” I stammered, not willing to admit that I had never actually tasted ravioli. (It may be difficult for people to believe, since Indian and Thai food are commonplace and sushi is consumed by everyone these days, but in the very early fifties in suburban New Jersey ravioli was considered only slightly less exotic than marinated larks’ tongues.) “Lasagna?” he inquired. By now I was a little flustered. “What’s …? I’m not sure I … I … I don’t really know what it is,” I finally admitted.

He raised his rather bushy eyebrows in mild amazement. Apparently my ignorance of the nature of lasagna was the final straw. The friar shook his head vigorously. “You have made a mistake. We are the Italian Capuchins. You must go to the German Capuchins. If you do not, you will starve!”

And that was that. Soon my father and I were on the road home to Caldwell, and I was completely deflated. I had expected to be asked about my spiritual life. I had been ready, willing, and able to expound on my breathtaking understanding of Francis, of Bonaventure, of Clare, of the Franciscan charism. I had been prepared to talk of the spiritual life, of prayer, of my desire to work with the poor. I could even name a decent number of papal encyclicals! But I had never expected to be asked about food. Could my entrance into the Capuchins really have been derailed due to a difference in gastronomic temperament?

“Lasagna,” I kept saying on the ride home. What could it be, and why was it so important?

The Tales Father Wasn’t Given the Time to Tell

God didn’t provide Fr. Benedict enough time to discuss what happened next in his attempt to become a member of the Friars Minor Capuchin, but it is very clear that this first rather disappointing attempt was not his last. He obviously did follow the advice of the friar from the Italian Capuchin province, and he quickly located the German Capuchins. The nearest ones turned out to be not far away at all, which must have been a relief to Pete Groeschel. They were headquartered in New York City, at St. John the Baptist Church, which was on 31st Street virtually across the street from Pennsylvania Station. The location could hardly have been more convenient for a boy from New Jersey. He just had to step off a train and he’d be there. Knowing Fr. Benedict and the determination of which he was capable, I have no doubt that he encountered his second Capuchin within a very few weeks of meeting his first.

Entering a religious order at the time was neither a casual nor slapdash affair. In fact, it could be rather grueling. A young man who had hopes of doing so would have to meet first with the vocation director of the order, whose job was (at least in part) to size him up quite thoroughly. A visit from the vocation director to the candidate’s home to meet the young man’s family was frequently a part of the process. Such visits were often unannounced, catching people off guard, and completely flustering quite a few unprepared families. A candidate would not be considered without a strong recommendation from his pastor and the unqualified support of a spiritual director. In all probability Pete Groeschel’s spiritual director at the time was Fr. McCarthy, the senior curate at Immaculate Conception Church. (It is also probable that Fr. McCarthy was Pete’s informal coach in preparing for public-speaking competitions.) Pete would certainly have been able to attain a glowing recommendation from Fr. McCarthy, who thought highly of him and was doing all he could to further the young man’s vocation. And a recommendation from his pastor would have been just as forthcoming.

A few weekend visits of the candidate to the religious community’s nearest house would be a common part of the process for a potential candidate, as well, and it is almost certain that Pete made these visits to the friary on 31st Street. There he would have gotten his first glimpse of friars in their daily life and began to grasp a bit of what being a Capuchin really meant.

It should be remembered that in the early fifties religious orders could be quite selective. They had many applicants, usually more than they wanted, and they were not slow to send a candidate packing if they deemed him inappropriate. A small misstep made by a candidate or even by a member of his family could result in a polite suggestion to begin investigating another religious community. Apparently Pete Groeschel made no such missteps, and equally apparent the Capuchins he encountered in New York were reasonably sure they had found a good candidate in him. There is neither a record of any problem, nor does anyone who recalls that time in Pete’s life remember any difficulty that he encountered in entering the religious order of his choice.

So it seemed that despite his lack of knowledge of Italian cuisine, Pete Groeschel was on his way to living the life he dreamed of.

3 Hall, Belief, 53