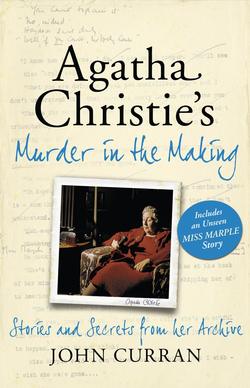

Читать книгу Agatha Christie’s Murder in the Making: Stories and Secrets from Her Archive - includes an unseen Miss Marple Story - John Curran - Страница 12

The Mysterious Affair at Styles

ОглавлениеThe story so far …

When wealthy Emily Inglethorp, owner of Styles Court, remarries, her new husband Alfred is viewed by her stepsons, John and Lawrence, and her faithful retainer, Evelyn Howard, as a fortune-hunter. John’s wife, Mary, is perceived as being over-friendly with the enigmatic Dr Bauerstein, a German and an expert on poisons. Also staying at Styles Court, while working in the dispensary of the local hospital, is Emily’s protégée Cynthia Murdoch. Then Evelyn walks out after a bitter row. On the night of 17 July Emily dies from strychnine poisoning while her family watches helplessly. Hercule Poirot, called in by his friend Arthur Hastings, agrees to investigate and pays close attention to Emily’s bedroom. And then John Cavendish is arrested …

Poirot returned late that night.3 I did not see him until the following morning. He was beaming and greeted me with the utmost affection.

‘Ah, my friend – all is well – all will now march.’

Notebook 37 showing the beginning of the deleted chapter from The Mysterious Affair at Styles.

‘Why,’ I exclaimed, ‘You don’t mean to say you have got—’

‘Yes, Hastings, yes – I have found the missing link.4 Hush …’

On Monday the hearing was resumed5 and Sir E.H.W. [Ernest Heavywether] opened the case for the defence. Never, he said, in the course of his experience had a murder charge rested on slighter evidence. Let them take the evidence against John Cavendish and sift it impartially.

What was the main thing against him? That the powdered strychnine had been found in his drawer. But that drawer was an unlocked one and he submitted that there was no evidence to show that it was the prisoner who placed it there. It was, in fact, a wicked and malicious effort on the part of some other person to bring the crime home to the prisoner. He went on to state that the Prosecution had been unable to prove to any degree that it was the prisoner who had ordered the beard from Messrs Parksons. As for the quarrel with his mother and his financial constraints – both had been most grossly exaggerated.

His learned friend had stated that if [the] prisoner had been an honest man he would have come forward at the inquest and explained that it was he and not his step-father who had been the participator in that quarrel. That view was based upon a misapprehension. The prisoner, on returning to the house in the evening, had been told at once6 that his mother had now had a violent dispute with her husband. Was it likely, was it probable, he asked the jury, that he should connect the two? It would never enter his head that anyone could ever mistake his voice for that of Mr. A[lfred] Inglethorp. As for the construction that [the] prisoner had destroyed a will – this mere idea was absurd. [The] prisoner had presented at the Bar and, being well versed in legal matters, knew that the will formerly made in his favour was revoked automatically. He had never heard a more ridiculous suggestion! He would, however, call evidence which would show who did destroy the will, and with what motive.

Finally, he would point out to the jury that there was evidence against other persons besides John Cavendish. He did not wish to accuse Mr. Lawrence Cavendish in any way; nevertheless, the evidence against him was quite as strong – if not stronger – than that against his brother.

Just at that point, a note was handed to him. As he read it, his eyes brightened, his burly figure seemed to swell and double its size.

‘Gentlemen of the jury,’ he said, and there was a new ring in his voice, ‘this has been a murder of peculiar cunning and complexity. I will first call the prisoner. He shall tell you his own story and I am sure you will agree with me that he cannot be guilty. Then I will call a Belgian gentleman, a very famous member of the Belgian police force in past years, who has interested himself in the case and who has important proofs that it was not the prisoner who committed this crime. I call the prisoner.’

John in the box acquitted himself well. His manner, quiet and direct, was all in his favour.7 At the end of his examination he paused and said, ‘I should like to say one thing. I utterly refute and disapprove of Sir Ernest Heavywether’s insinuation about my brother Lawrence. My brother, I am convinced, had no more to do with this crime than I had.’

Sir Ernest, remaining seated, noted with a sharp eye that John’s protest had made a favourable effect upon the jury. Mr Bunthorne cross-examined.8

‘You say that you never thought it possible that your quarrel with your mother was identical with the one spoken of at the inquest – is not that very surprising?’

‘No, I do not think so – I knew that my mother and Mr Inglethorp had quarrelled. It never occurred to me that they had mistaken my voice for his.’

‘Not even when the servant Dorcas repeated certain fragments of this conversation which you must have recognised?’

‘No, we were both angry and said many things in the heat of the moment which we did not really mean and which we did not recollect afterwards. I could not have told you which exact words I used.’

Mr Bunthorne sniffed incredulously.

‘About this note which you have produced so opportunely, is the handwriting not familiar to you?’

‘No.’

‘Do you not think it bears a marked resemblance to your own handwriting?’

‘No – I don’t think so.’

‘I put it to you that it is your own handwriting.’

‘No.’

‘I put it to you that, anxious to prove an alibi, you conceived the idea of a fictitious appointment and wrote this note to yourself in order to bear out your statement.’

‘No.’

‘I put it to you that at the time you claim to have been waiting about in Marldon Wood,9 you were really in Styles St Mary, in the chemist’s shop, buying strychnine in the name of Alfred Inglethorp.’

‘No – that is a lie.’

That completed Mr Bunthorne’s CE [cross examination]. He sat down and Sir Ernest, rising, announced that his next witness would be M. Hercule Poirot.

Poirot strutted into the witness box like a bantam cock.10 The little man was transformed; he was foppishly attired and his face beamed with self confidence and complacency. After a few preliminaries Sir Ernest asked: ‘Having been called in by Mr. Cavendish what was your first procedure?’

‘I examined Mrs Inglethorp’s bedroom and found certain …?’

‘Will you tell us what these were?’

‘Yes.’

With a flourish Poirot drew out his little notebook.

‘Voila,’ he announced, ‘There were in the room five points of importance.11 I discovered, amongst other things, a brown stain on the carpet near the window and a fragment of green material which was caught on the bolt of the communicating door between that room and the room adjoining, which was occupied by Miss Cynthia Paton.’12

‘What did you do with the fragment of green material?’

‘I handed it over to the police, who, however, did not consider it of importance.’

‘Do you agree?’

‘I disagree with that most utterly.’

‘You consider the fragment important?’

‘Of the first importance.’

‘But I believe,’ interposed the judge, ‘that no-one in the house had a green garment in their possession.’

‘I believe so, Mr Le Juge,’ agreed Poirot facing in his direction. ‘And so at first, I confess, that disconcerted me – until I hit upon the explanation.’

Everybody was listening eagerly.

‘What is your explanation?’

‘That fragment of green was torn from the sleeve of a member of the household.’

‘But no-one had a green dress.’

‘No, Mr Le Juge, this fragment is a fragment torn from a green land armlet.’

With a frown the judge turned to Sir Ernest.

‘Did anyone in that house wear an armlet?’

‘Yes, my lord. Mrs Cavendish, the prisoner’s wife.’

There was a sudden exclamation and the judge commented sharply that unless there was absolute silence he would have the court cleared. He then leaned forward to the witness.

‘Am I to understand that you allege Mrs Cavendish to have entered the room?’

‘Yes, Mr Le Juge.’

‘But the door was bolted on the inside.’

‘Pardon, Mr Le Juge, we have only one person’s word for that – that of Mrs Cavendish herself. You will remember that it was Mrs Cavendish who had tried that door and found it locked.’

‘Was not her door locked when you examined the room?’

‘Yes, but during the afternoon she would have had ample opportunity to draw the bolt.’13

‘But Mr Lawrence Cavendish has claimed that he saw it.’

There was a momentary hesitation on Poirot’s part before he replied.

‘Mr. Lawrence Cavendish was mistaken.’

Poirot continued calmly:

‘I found, on the floor, a large splash of candle grease, which upon questioning the servants, I found had not been there the day before. The presence of the candle grease on the floor, the fact that the door opened quite noiselessly (a proof that it had recently been oiled) and the fragment of the green armlet in the door led me at once to the conclusion that the room had been entered through that door and that Mrs Cavendish was the person who had done so. Moreover, at the inquest Mrs Cavendish declared that she had heard the fall of the table in her own room. I took an early opportunity of testing that statement by stationing my friend Mr Hastings14 in the left wing just outside Mrs Cavendish’s door. I myself, in company with the police, went to [the] deceased’s room and whilst there I, apparently accidentally, knocked over the table in question but found, as I had suspected, that [it made] no sound at all. This confirmed my view that Mrs Cavendish was not speaking the truth when she declared that she had been in her room at the time of the tragedy. In fact, I was more than ever convinced that, far from being in her own room, Mrs Cavendish was actually in the deceased’s room when the table fell. I found that no one had actually seen her leave her room. The first that anyone could tell me was that she was in Miss Paton’s room shaking her awake. Everyone presumed that she had come from her own room – but I can find no one who saw her do so.’

The judge was much interested. ‘I understand. Then your explanation is that it was Mrs Cavendish and not the prisoner who destroyed the will.’

Poirot shook his head.

‘No,’ he said quickly, ‘That was not the reason for Mrs Cavendish’s presence. There is only one person who could have destroyed the will.’

‘And that is?’

‘Mrs Inglethorp herself.’

‘What? The will she had made that very afternoon?’

‘Yes – it must have been her. Because by no other means can you account for the fact that on the hottest day of the year [Mrs Inglethorp] ordered a fire to be lighted in her room.’

The judge objected. ‘She was feeling ill …’

‘Mr Le Juge, the temperature that day was 86 in the shade. There was only one reason for which Mrs Inglethorp could want a fire – namely to destroy some document. You will remember that in consequence of the war economies practised at Styles, no waste paper was thrown away and that the kitchen fire was allowed to go out after lunch. There was, consequently, no means at hand for the destroying of bulky documents such as a will. This confirms to me at once that there was some paper which Mrs Inglethorp was anxious to destroy and it must necessarily be of a bulk which made it difficult to destroy by merely setting a match to it. The idea of a will had occurred to me before I set foot in the house, so papers burned in the grate did not surprise me. I did not, of course, at that time know that the will in question had only been made the previous afternoon and I will admit that when I learnt this fact, I fell into a grievous error. I deduced that Mrs Inglethorp’s determination to destroy this will came as a direct consequence of the quarrel and that consequently the quarrel took place, contrary to belief, after the making of the will.

‘When, however, I was forced to reluctantly abandon this hypothesis – since the various interviews were absolutely steady on the question of time – I was obliged to cast around for another. And I found it in the form of the letter which Dorcas describes her mistress as holding in her hand. Also you will notice the difference of attitude. At 3.30 Dorcas overhears her mistress saying angrily that “scandal will not deter her.” “You have brought it on yourself” were her words. But at 4.30, when Dorcas brings in the tea, although the actual words she used were almost the same, the meaning is quite different. Mrs Inglethorp is now in a clearly distressed condition. She is wondering what to do. She speaks with dread of the scandal and publicity. Her outlook is quite different. We can only explain this psychologically by presuming [that] her first sentiments applied to the scandal between John Cavendish and his wife and did not in any way touch herself – but that in the second case the scandal affected herself.

‘This, then, is the position: At 3.30 she quarrels with her son and threatens to denounce him to his wife who, although they neither of them realise it, overhears part of the conversation. At 4 o’clock, in consequence of a conversation at lunch time on the making of wills by marriage, Mrs Inglethorp makes a will in favour of her husband, witnessed by her gardener. At 4.30 Dorcas finds her mistress in a terrible state, a slip of paper in her hand. And she then orders the fire in her room to be lighted in order that she can destroy the will she only made half an hour ago. Later she writes to Mr Wells, her lawyer, asking him to call on her tomorrow as she has some important business to transact.

Now what occurred between 4 o’clock and 4.3015 to cause such a complete revolution of sentiments? As far as we know, she was quite alone during the time. Nobody entered or left the boudoir. What happened then? One can only guess but I have an idea that my guess is fairly correct.

‘Late in the evening Mrs Inglethorp asked Dorcas for some stamps and my thinking is this. Finding she had no stamps in her desk she went along to that of her husband which stood at the opposite corner. The desk was locked but one of the keys on her bunch fitted it. She accordingly opened the desk and searched for stamps – it was then she found the slip of paper which wreaked such havoc! On the other hand Mrs Cavendish believed that the slip of paper to which her mother [in-law] clung so tenaciously was a written proof of her husband’s infidelity. She demanded it. These were Mrs Inglethorp’s words in reply:

‘“No, [it is out of the] question.” We know that she was speaking the truth. Mrs Cavendish however, believed she was merely shielding her step-son. She is a very resolute woman and she was wildly jealous of her husband and she determined to get hold of that paper at all costs and made her plans accordingly. She had chanced to find the key of Mrs Inglethorp’s dispatch case which had been lost that morning. She had meant to return it but it had probably slipped her memory. Now, however, she deliberately retained it since she knew Mrs Inglethorp kept all important papers in that particular case. Therefore, rising about 4 o’clock she made her way through Miss Paton’s room, which she had previously unlocked on the other side.’

‘But Miss Paton would surely have been awakened by anyone passing through her room.’

‘Not if she were drugged.’

‘Drugged?’

‘Yes – for Miss Paton to have slept through all the turmoil in that next room was incredible. Two things were possible: either she was lying (which I did not believe) or her sleep was not a natural one. With this idea in view I examined all the coffee cups most carefully, taking a sample from each and analysing. But, to my disappointment, they yielded no result. Six persons had taken coffee and six cups were found. But I had been guilty of a very grave oversight. I had overlooked the fact that Dr Bauerstein had been there that night. That changed the face of the whole affair. Seven, not six people had taken coffee. There was, then, a cup missing. The servants would not observe this since it was the housemaid Annie who had taken the coffee tray in and she had brought in seven cups, unaware that Mr Inglethorp never took coffee. Dorcas who cleared them away found five cups and she suspected the sixth [of] being Mrs Inglethorp’s. One cup, then, had disappeared and it was Mademoiselle Cynthia’s, I knew, because she did not take sugar in her coffee, whereas all the others did and the cups I had found had all contained sugar. My attention was attracted by the maid Annie’s story about some “salt” on the cocoa tray which she took nightly into Mrs Inglethorp’s room. I accordingly took a sample of that cocoa and sent it to be analysed.’

‘But,’ objected the judge, ‘this has already been done by Dr Bauerstein – with a negative result – and the analysis reported no strychnine present.’

‘There was no strychnine present. The analysts were simply asked to report whether the contents showed if there were or were not strychnine present and they reported accordingly. But I had it tested for a narcotic.’

‘For a narcotic?’

‘Yes, Mr Le Juge. You will remember that Dr Bauerstein was unable to account for the delay before the symptoms manifested themselves. But a narcotic, taken with strychnine, will delay the symptoms some hours. Here is the analyst’s report proving beyond a doubt that a narcotic was present.’

The report was handed to the judge who read it with great interest and it was then passed on to the jury.

‘We congratulate you on your acumen. The case is becoming much clearer. The drugged cocoa, taken on top of the poisoned coffee, amply accounts for the delay which puzzled the doctor.’

‘Exactly, Mr Le Juge. Although you have made one little error; the coffee, to the best of my belief was not poisoned.’

‘What proof have you of that?’

‘None whatever. But I can prove this – that poisoned or not, Mrs Inglethorp never drank it.’

‘Explain yourself.’

‘You remember that I referred to a brown stain on the carpet near the window? It remained in my mind, that stain, for it was still damp. Something had been spilt there, therefore, not more than twelve hours ago. Moreover there was a distinct odour of coffee clinging to the nap of the carpet and I found there two long splinters of china. I later reconstructed what had happened perfectly, for, not two minutes before I had laid down my small despatch case on the little table by the window and, the top of the table being loose, the case had been toppled off onto the floor onto the exact spot where the stain was. This, then, was what had happened. Mrs Inglethorp, on coming up to bed had laid her untasted coffee down on the table – the table had tipped up and [precipitated] the coffee onto the floor – spilling it and smashing the cup. What had Mrs Inglethorp done? She had picked up the pieces and laid them on the table beside her bed and, feeling in need of a stimulant of some kind, had heated up her cocoa16 and drank it off before going to bed. Now, I was in a dilemma. The cocoa contained no strychnine. The coffee had not been drunk. Yet Mrs Inglethorp had been poisoned and the poison must have been administered sometime between the hours of seven and nine. But what else had Mrs Inglethorp taken which would have effectively masked the taste of the poison?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Yes – Mr Le Juge – she had taken her medicine.’

‘Her medicine – but …’

‘One moment – the medicine, by a [coincidence] already contained strychnine and had a bitter taste in consequence. The poison might have been introduced into the medicine. But I had my reasons for believing that it was done another way. I will recall to your memory that I also discovered a box which had at one time contained bromide powders. Also, if you will permit it, I will read out to you an extract – marked in pencil – out of a book on dispensing which I noticed at the dispensary of the Red Cross Hospital at Tadminster. The following is the extract …’17

‘But, surely a bromide was not prescribed with the tonic?’

‘No, Mr Le Juge. But you will recall that I mentioned an empty box of bromide powders. One of the powders introduced into the full bottle of medicine would effectively precipitate the strychnine and cause it to be taken in the last dose. You may observe that the “Shake the bottle” label always found on bottles containing poison has been removed. Now, the person who usually poured out the medicine was extremely careful to leave the sediment at the bottom undisturbed.’

A fresh buzz of excitement broke out and was sternly silenced by the judge.

‘I can produce a rather important piece of evidence in support of that contention, because on reviewing the case, I came to the conclusion18 that the murder had been intended to take place the night before. For in the natural course of events Mrs I[nglethorp] would have taken the last dose on the previous evening but, being in a hurry to see to the Fashion Fete she was arranging, she omitted to do so. The following day she went out to luncheon, so that she took the actual last dose 24 hours later than had been anticipated by the murderer. As a proof that it was expected the night before, I will mention that the bell in Mrs Inglethorp’s room was found cut on Monday evening, this being when Miss Paton was spending the night with friends. Consequently Mrs Inglethorp would be quite cut off from the rest of the house and would have been unable to arouse them, thereby making sure that medical aid would not reach her until too late.’

‘Ingenious theory – but have you no proof?’

Poirot smiled curiously.

‘Yes, Mr Le Juge – I have a proof. I admit that up to some hours ago, I merely knew what I have just said, without being able to prove it. But in the last few hours I have obtained a sure and certain proof, the missing link in the chain, a link in the murderer’s own hand, the one slip he made. You will remember the slip of paper held in Mrs Inglethorp’s hand? That slip of paper has been found. For on the morning of the tragedy the murderer entered the dead woman’s room and forced the lock of the despatch case. Its importance can be guessed at from the immense risks the murderer took. There was one risk he did not take – and that was the risk of keeping it on his own person – he had no time or opportunity to destroy it. There was only one thing left for him to do.’

Notebook 37 showing the end of the deleted chapter from The Mysterious Affair at Styles. See Footnote 19.

‘What was that?’

‘To hide it. He did hide it and so cleverly that, though I have searched for two months it is not until today that I found it. Voila, ici le prize.’

With a flourish Poirot drew out three long slips of paper.

‘It has been torn – but it can easily be pieced together. It is a complete and damning proof.19 Had it been a little clearer in its terms it is possible that Mrs Inglethorp would not have died. But as it was, while opening her eyes to who, it left her in the dark as to how. Read it, Mr Le Juge. For it is an unfinished letter from the murderer, Alfred Inglethorp, to his lover and accomplice, Evelyn Howard.’

And there, like Alfred Inglethorp’s pieced-together letter at the end of Chapter 12, Notebook 37 breaks off, despite the fact that the following pages are blank. We know from the published version that Alfred Inglethorp and Evelyn Howard are subsequently arrested for the murder, John and Mary Cavendish are reconciled, Cynthia and Lawrence announce their engagement, while Dr Bauerstein is shown to be more interested in spying than in poisoning. The book closes with Poirot’s hope that this investigation will not be his last with ‘mon ami’ Hastings.

The reviews on publication were as enthusiastic as the pre-publication reports for John Lane. The Times called it ‘a brilliant story’ and the Sunday Times found it ‘very well contrived’. The Daily News considered it ‘a skilful tale and a talented first book’, while the Evening News thought it ‘a wonderful triumph’ and described Christie as ‘a distinguished addition to the list of writers in this [genre]’. ‘Well written, well proportioned and full of surprises’ was the verdict of The British Weekly.

Poirot’s dramatic evidence in the course of the trial resembles a similar scene at the denouement of Leroux’s The Mystery of the Yellow Room (1907), where the detective, Rouletabille, gives his remarkable and conclusive evidence from the witness box. Had John Lane but known it, in demanding the alteration to the denouement of the novel he unwittingly paved the way for a half century of drawing-room elucidations stage-managed by both Poirot and Miss Marple. And although this explanation, in both courtroom and drawing room, is essentially the same, the unlikelihood of a witness being allowed to give evidence in this manner is self-evident. In other ways also The Mysterious Affair at Styles presaged what was to become typical Christie territory – an extended family, a country house, a poisoning drama, a twisting plot, and a dramatic and unexpected final revelation.

It is not a very extended family, however. Of Mrs Inglethorp’s family, there is a husband, two stepsons, one daughter-in-law, a family friend, a companion and a visiting doctor; there is the usual domestic staff although none of them is ever a serious consideration as a suspect. In other words, there are only seven suspects, which makes the disclosure of a surprise murderer more difficult. This very limited circle makes Christie’s achievement in her first novel even more impressive. The usual clichéd view of Christie is that all of her novels are set in country houses and/or country villages. Statistically, this is inaccurate. Less than 30 (i.e. little over a third) of her titles are set in such surroundings, and the figure drops dramatically if you discount those set completely in a country house, as distinct from a village. But as Christie herself said, you have to set a book where people live.

Some ideas that feature in The Mysterious Affair at Styles would appear again throughout Christie’s career. The dying Emily Inglethorp calls out the name of her husband, ‘Alfred … Alfred’, before she finally succumbs. Is the use of his name an accusation, an invocation, a plea, a farewell; or is it entirely meaningless? Similar situations occur in several novels over the next 30 years. One novel, Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?, is built entirely around the dying words of the man found at the foot of the cliffs. In Death Comes as the End, the dying Satipy calls the name of the earlier victim, ‘Nofret’; as John Christow lies dying at the edge of the Angkatells’ swimming pool, in The Hollow, he calls out the name of his lover, ‘Henrietta.’ An extended version of the idea is found in A Murder is Announced when the last words of the soon-to-be-murdered Amy Murgatroyd, ‘she wasn’t there’, contain a vital clue and are subjected to close examination by Miss Marple. Both Murder in Mesopotamia – ‘the window’ – and Ordeal by Innocence – ‘the cup was empty’ and ‘the dove on the mast’ – give clues to the method of murder. And the agent Carmichael utters the enigmatic ‘Lucifer … Basrah’ before he expires in Victoria’s room in They Came to Baghdad.

The idea of a character looking over a shoulder and seeing someone or something significant makes its first appearance in Christie’s work when Lawrence looks horrified at something he notices in Mrs Inglethorp’s room on the night of her death. The alert reader should be able to tell what it is. This ploy is a Christie favourite and she enjoyed ringing the changes on the possible explanations. She predicated at least two novels – The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side and A Caribbean Mystery – almost entirely on this, and it makes noteworthy appearances in The Man in the Brown Suit, Appointment with Death and Death Comes as the End, as well as a handful of short stories.

In the 1930 stage play Black Coffee,20 the only original script to feature Hercule Poirot, the hiding-place of the papers containing the missing formula is the same as the one devised by Alfred Inglethorp. And in an exchange very reminiscent of a similar one in The Mysterious Affair at Styles, it is a chance remark by Hastings that leads Poirot to this realisation.

In common with many crime stories of the period there are two floor-plans and no less than three reproductions of handwriting. Each has a part to play in the eventual solution. And here also we see for the first time Poirot’s remedy for steadying his nerves and encouraging precision in thought: the building of card-houses. At crucial points in both Lord Edgware Dies and Three Act Tragedy he adopts a similar strategy, each time with equally triumphant results. The important argument overheard by Mary Cavendish through an open window in Chapter 6 foreshadows a similar and equally important case of eavesdropping in Five Little Pigs.

In his 1953 survey of detective fiction, Blood in their Ink, Sutherland Scott describes The Mysterious Affair at Styles as ‘one of the finest “firsts” ever written’. Countless Christie readers over almost a century would enthusiastically agree.

The Secret of Chimneys

12 June 1925

A shooting party weekend at the country house Chimneys conceals the presence of international diplomats negotiating lucrative oil concessions with the kingdom of Herzoslovakia. When a dead body is found, Superintendent Battle’s subsequent investigation uncovers international jewel thieves, impersonation and kidnapping as well as murder.

‘These were easy to write, not requiring too much plotting or planning.’ In her Autobiography, Agatha Christie makes only this fleeting reference to The Secret of Chimneys, first published in the summer of 1925 as the last of the six books she had contracted to produce for John Lane when they accepted The Mysterious Affair at Styles. In this ‘easy to write’ category she also included The Seven Dials Mystery, published in 1929, and, indeed, the later title features many of the same characters as the earlier.

The Secret of Chimneys is not a formal detective story but a light-hearted thriller, a form to which she returned throughout her writing career with The Man in the Brown Suit, The Seven Dials Mystery, Why Didn’t they ask Evans? and They Came to Baghdad. The Secret of Chimneys has all the ingredients of a good thriller of the period – missing jewels, a mysterious manuscript, compromising letters, oil concessions, a foreign throne, villains, heroes, and mysterious and beautiful women. It has distinct echoes of The Prisoner of Zenda, Anthony Hope’s immortal swashbuckling novel that Tuppence recalls with affection in Chapter 2 of Postern of Fate – ‘one’s first introduction, really, to the romantic novel. The romance of Prince Flavia. The King of Ruritania, Rudolph Rassendyll …’ Christie organised these classic elements into a labyrinthine plot and also managed to incorporate a whodunit element.

The story begins in Africa, a country Christie had recently visited on her world tour in the company of her husband Archie. The protagonist, the somewhat mysterious Anthony Cade, undertakes to deliver a package to an address in London. This seemingly straightforward mission proves difficult and dangerous and before he can complete it he meets the beautiful Virginia Revel, who also has a commission for him – to dispose of the inconveniently dead body of her blackmailer. This achieved, they meet again at Chimneys, the country estate of Lord Caterham and his daughter Lady Eileen ‘Bundle’ Brent. From this point on, we are in more ‘normal’ Christie territory, the country house with a group of temporarily isolated characters – and one of them a murderer.

That said, it must be admitted that a hefty suspension of disbelief is called for if some aspects of the plot are to be accepted. We are asked to believe that a young woman will pay a blackmailer a large sum of money (£40 in 1930 has the purchasing power today of roughly £1,500) for an indiscretion that she did not commit, just for the experience of being blackmailed (Chapter 7), and that two chapters later when the blackmailer is found inconveniently, and unconvincingly, dead in her sitting room, she asks the first person who turns up on her doorstep (literally) to dispose of the body, while she blithely goes away for the weekend. By its nature this type of thriller is light-hearted, but The Secret of Chimneys demands much indulgence on the part of the reader.

The hand of Christie the detective novelist is evident in elements of the narration. Throughout the book the reliability of Anthony Cade is constantly in doubt and as early as Chapter 1 he jokes with his tourist group (and, by extension, the reader) about his real name. This is taken as part of his general banter but, as events unfold, he is revealed to be speaking nothing less than the truth. For the rest of the book Christie makes vague statements about Cade and when we are given his thoughts they are, in retrospect, ambiguous.

Anthony looked up sharply.

‘Herzoslovakia?’ he said with a curious ring in his voice. [Chapter 1]

‘… was it likely that any of them would recognise him now if they were to meet him face to face?’ [Chapter 5]

‘No connexion with Prince Michael’s death, is there?’

His hand was quite steady. So were his eyes. [Chapter 18]

‘The part of Prince Nicholas of Herzoslovakia.’

The matchbox fell from Anthony’s hand, but his amazement was fully equalled by that of Battle. [Chapter 19]

‘I’m really a king in disguise, you know’ [Chapter 23]

And how many readers will wonder about the curious scene at the end of Chapter 16 when Anchoukoff, the manservant, tells him he ‘will serve him to the death’ and Anthony ponders on ‘the instincts these fellows have’? Anthony’s motives remain unclear until the final chapter, and the reader, despite the hints contained in the above quotations, is unlikely to divine his true identity and purpose.

There are references, unconscious or otherwise, to other Christie titles. The rueful comments in Chapter 5 when Anthony remarks, ‘I know all about publishers – they sit on manuscripts and hatch ’em like eggs. It will be at least a year before the thing is published,’ echo Christie’s own experiences with John Lane and the publication of The Mysterious Affair at Styles five years earlier. The ploy of leaving a dead body in a railway left-luggage office, adopted by Cade in Chapter 9, was used in the 1923 Poirot short story ‘The Adventure of the Clapham Cook’. Lord Caterham’s description of the finding of the body in Chapter 10 distinctly foreshadows a similar scene almost 20 years later in The Body in the Library when Colonel Bantry shares his unwelcome experience. And Virginia Revel’s throwaway comments about governesses and companions in Chapter 22 – ‘It’s awful but I never really look at them properly. Do you?’ – would become the basis of more than a few future Christie plots, among them Death in the Clouds, After the Funeral and Appointment with Death. The same chapter is called ‘The Red Signal’, also the title of a short story from The Hound of Death (see Chapter 3). Both this chapter and the short story share a common theme.

There are a dozen pages of notes in Notebook 65 for the novel, consisting mainly of a list of chapters and their possible content with no surprises or plot variations. But the other incarnation of The Secret of Chimneys makes for more interesting reading. Until recently this title was one of the few Christies not adapted for stage, screen or radio. Or so it was thought, until it emerged that the novel was actually, very early in her career, Christie’s first stage adaptation. The history of the play is, appropriately, mysterious. It was scheduled to appear at the Embassy Theatre in London in December 1931 but was replaced at the last moment by a play called Mary Broome, a twenty-year-old comedy by one Allan Monkhouse. The Embassy Theatre no longer exists and research has failed to discover a definitive reason for the last-minute cancellation and substitution. Almost a year before the proposed staging of Chimneys, Christie was writing from Ashfield in Torquay to her new husband, Max Mallowan, who was on an archaeological dig. Rather than clarifying the sequence of events, these letters make the cancellation of the play even more mystifying:

Tuesday [16 December 1930] Very exciting – I heard this morning an aged play of mine is going to be done at the Embassy Theatre for a fortnight with a chance of being given West End production by the Reandco [the production company]. Of course nothing may come of it but it’s exciting anyway. Shall have to go to town for a rehearsal or two end of November.

Dec. 23rd [1930] Chimneys is coming on here but nobody will say when. I fancy they want something in Act I altered and didn’t wish to do it themselves.

Dec. 31st [1930] If Chimneys is put on 23rd I shall stay for the first night. If it’s a week later I shan’t wait for it. I don’t want to miss Nineveh and I shall have seen rehearsals, I suppose.

A copy of the script was lodged with the Lord Chamberlain on 19 November 1931 and approved within the week, and rehearsals were under way. But it was discovered that, due possibly to an administrative oversight, the licence to produce the play had expired on 10 October 1931. Why it was not simply renewed in order to allow the play to proceed is not clear but it may have been due to financial considerations, because at the end of February 1932 the theatre closed, to reopen two months later under new management, the former company Reandco (Alec Rea and Co.) having sold its interest. But it must be admitted that this theory is speculative.

Whatever happened during the final preparations, Christie herself was clearly unaware of any problems and was as surprised and as puzzled as anyone at the outcome. The last two references to the play appear in letters written during her journey home, via the Orient Express, in late 1931 from visiting Max in Nineveh. The dating of the letters is tentative, for she was as slipshod about dating letters as she was about dating Notebooks.

[Mid November 1931] I am horribly disappointed. Just seen in the Times that Chimneys begins Dec. 1st so I shall just miss it. Really is disappointing

[Early December 1931] Am now at the Tokatlian [Hotel in Istanbul] and have looked at Times of Dec 7th. And ‘Mary Broome’ is at the Embassy!! So perhaps I shall see Chimneys after all? Or did it go off after a week?

And that was the last that was heard of Chimneys for over 70 years, until a copy of the manuscript appeared, equally mysteriously, on the desk of the Artistic Director of the Vertigo Theatre in Calgary, Canada. So, almost three-quarters of a century after its projected debut, the premiere of Chimneys took place on 11 October 2003. And in June 2006, UK audiences had the opportunity to see this ‘lost’ Agatha Christie play, when it was presented at the Pitlochry Theatre Festival.

It is not known when exactly or, indeed, why Christie decided to adapt this novel for the stage. The use of the word ‘aged’ in the first letter quoted above would seem to indicate that it was undertaken long before interest was shown in staging it. The adaptation was probably done during late 1927/early 1928; a surviving typescript is dated July 1928. This would tally with the notes for the play; they are contained in the Notebook that has very brief, cryptic notes for some of the stories in The Thirteen Problems, the first of which appeared in December 1927. Nor does The Secret of Chimneys lend itself easily, or, it must be said, convincingly, to adaptation. If Christie decided in the late 1920s to dramatise one of her titles, one possible reason for choosing The Secret of Chimneys may have been her reluctance to put Poirot on the stage. She dropped him from four adaptations in later years – Murder on the Nile, Appointment with Death, The Hollow and Go Back for Murder (Five Little Pigs). The only play thus far to feature him was the original script, Black Coffee, staged the year before the proposed presentation of Chimneys. Yet, if she had wanted to adapt an earlier title, surely The Mysterious Affair at Styles or even The Murder on the Links would have been easier, set as they are largely in a single location and therefore requiring only one stage setting?

Perhaps with this in mind, the adaptation of The Secret of Chimneys is set entirely in Chimneys. This necessitated dropping large swathes of the novel (including the early scenes in Africa and the disposal, by Anthony, of Virginia’s blackmailer) or redrafting these scenes for delivery as speeches by various characters. This tends to make for a clumsy Act I, demanding much concentration from the audience as they are made aware of the back-story; but it is necessary in order to retain the plot. The second and third Acts are more smooth-running and, at times, quite sinister, with the stage in darkness and a figure with a torch making his way quietly across the set. There are also sly references, to be picked up by alert Christie aficionados, to ‘retiring and growing vegetable marrows’ and to the local town of Market Basing, a recurrent Christie location.

The solution propounded in the stage version is the earliest example of Christie altering her own earlier explanation. She was to do this throughout her career. On the stage she gave extra twists to And Then There Were None, Appointment with Death and Witness for the Prosecution; on the page, to ‘The Incident of the Dog’s Ball’/Dumb Witness, ‘Yellow Iris’/Sparkling Cyanide and ‘The Second Gong’/‘Dead Man’s Mirror’. In Chimneys she makes even more drastic alterations to the solution of the original; the character unmasked as the villain at the end of the novel does not even appear in the stage adaptation.

Some correspondence between Christie and Edmund Cork, her agent, in the summer of 1951 would seem to indicate that there were hopes of a revival, or to be strictly accurate, a debut of the play, due to the topicality of ‘recent developments in the oil business’; this is a reference to one of the elements of the plot, the question of oil concessions. But further developments in connection with a staging of the play, if any, remain unknown and it is clear that until Calgary in 2003 the script remained an ‘unknown’ Christie. The remote possibility that the script preceded the novel, which might have explained the unlikely choice of title for adaptation, is refuted by the reference in the opening pages of notes by the use of the phrase ‘Incidents likely to retain’.

There are amendments to the original novel in view of the fact that the entire play is set in Chimneys. As the play opens a weekend house party, arranged in order to conceal a more important international meeting, is about to begin, and by the opening of Act I, Scene ii the murder has been committed. And, in a major change from the novel, Anthony Cade and Virginia Revel are the ones to find the body, although they say nothing and allow the discovery to be made the following morning. In a scene very reminiscent of a similar one in Spider’s Web, Cade and Virginia examine the dead body and find the gun with Virginia’s name; in view of the danger in which this would place her, they agree to remain quiet about their discovery. In effect, Act II opens at Chapter 10 of the book and from there on both follow much the same plan.

A major divergence is the omission of the scenes involving the discovery and disposal, by Cade, of the blackmailer’s body. In fact, the entire blackmail scenario is substantially different. But whether written or staged, it is an unconvincing red herring and it could have been omitted entirely from the script without any loss. Other changes incorporated into the stage version include the fact that Virginia has no previous connection with Herzoslovakia, an aspect of the book that signally fails to convince. The secret passage from Chimneys to Wyvern Abbey is not mentioned, the character Hiram Fish has been dropped and the hiding place of the jewels is different from, and not as well clued as, that in the novel.

The Cast of Characters and Scenes of the Play from a 1928 script of Chimneys.

The notes for Chimneys are all contained in Notebook 67. It is a tiny, pocket-diary sized notebook and the handwriting is correspondingly small and frequently illegible. In addition to the very rough notes for some of The Thirteen Problems the Notebook contains sketches of some Mr Quin short stories, as well as notes for a dramatisation of the Quin story ‘The Dead Harlequin’. Overall, the notes for Chimneys do not differ greatly from the final version of the play, but substantial changes have been made from the original novel.

The first page reads:

People

Lord Caterham

Bundle

Lomax

Bill

Virginia

Tredwell

Antony

Prince Michael

Now what happens?

Incidents likely to retain – V[irginia] blackmailed

Idea of play

Crown jewels of Herzoslovakia stolen from assassinated King and Queen during house party at Chimneys – hidden there.

And twenty-five pages later she is amending her cast of characters:

Lord C

George

Bill

Tredwell

Battle

Inspector

Isaacstein

Bundle

Virginia

Antony

Lemaitre

Boris

The entire action of the play moves between the Library and the Council Chamber of Chimneys. The opening scene, which does not have an exact equivalent in the novel, introduces us to Lord Caterham, Bundle and George Lomax, the immensely discreet civil servant, arranging a top-level meeting that is to masquerade as a weekend shooting party. Chapter 16 of the novel has a brief reference to visitors being shown over the house and it is with such a brief scene that the play opens, as outlined below:

Act I Scene I – The Council Chamber

Lord C[aterham] in shabby clothes – Tredwell showing party over. ‘This is the ….’ A guest comes back for his hat tips Lord C. Bundle comes – ‘First bit [of honest money] ever earned by the Brents.’ She and Lord C – he complains of political party Lomax has dragged him into. Bundle says why does he do it? George arrives and B goes. Explanation etc. about Cade – the Memoirs – Streptiltich … the Press – the strain of public life etc. Mention of diamond – King Victor – stolen by the Queen, 3rd rate actress – more like a comic opera – she killed in revolution