Читать книгу Return of the Dambusters: What 617 Squadron Did Next - John Nichol - Страница 11

CHAPTER 3 Press On, Regardless

ОглавлениеBomber Command’s Main Force had continued to pound Germany during the autumn and early winter of 1943, including a raid on Kassel on 22/23 October that caused a week-long firestorm in the town and killed 10,000 people, and the launch of the ‘Battle of Berlin’, a six-month bombing campaign against the German capital, beginning on 18/19 November. Over the course of the campaign some 9,000 sorties would be flown and almost 30,000 tons of bombs dropped. Bomber Harris’s claim that though ‘it will cost us between 400–500 aircraft. It will cost Germany the war’1 proved optimistic; the aircraft losses were over twice as heavy and the bombing campaign did not destroy the city, nor the morale of its population, nor the Nazis’ willingness to continue the war. In contrast, the heavy losses sustained by Main Force during this period undoubtedly had an effect on morale.

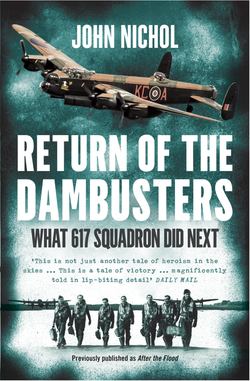

Following George Holden’s death at Dortmund–Ems, Mick Martin had been put in temporary charge of 617 Squadron, but because he had jumped two ranks from Flight Lieutenant direct to Wing Commander, some felt his face still did not fit, and on 10 November 1943 he was replaced by a new commander, a tall, dark-haired and gaunt-faced figure: Wing Commander Leonard Cheshire. Still only twenty-six, Cheshire was one of the RAF’s most decorated pilots and its youngest Group Captain, who had taken a drop in rank in order to command 617.

Cheshire made a dramatic entrance to his new squadron. Gunner Chan Chandler was in his room at the Petwood Hotel when there was a shot directly outside his window. ‘I looked out and saw this chap with a revolver in his hand, called him a bloody lunatic and asked what the hell he thought he was doing. He replied that he thought the place needed waking up! It turned out he was the new CO and my first words to him were to call him a bloody lunatic! However, we got on famously after that.’2

Leonard Cheshire

At his first squadron meeting Cheshire told his men that ‘If you get into trouble when you’re off duty, I will do what I can to help you. If you get into trouble on duty, I’ll make life a hell of a lot worse for you.’

‘So we all knew where we stood from the start,’ Johnny Johnson says. Far more approachable and friendly than Guy Gibson, Cheshire was soon highly thought of by all. ‘He developed the techniques for marking, for instance,’ Johnson says, ‘so the efficiency of the squadron was improved. That was always his objective: to get things absolutely right.’

Larry Curtis found Cheshire ‘very quiet, very relaxed, but at the same time, you did what you were told; he just approached it in a different way.’3 Malcolm ‘Mac’ Hamilton witnessed this new approach when he joined the squadron. His crew had achieved an impressive bombing accuracy of 70 yards before joining 617, and when he met Cheshire for the first time, Cheshire said, ‘Oh, Hamilton, I see your crew have won the 5 Group bombing trophy three months running.’

Hamilton acknowledged this, ‘putting my chest out, because I was quite proud’.

Cheshire frowned. ‘Well, I tell you what I’ll do. I’ll give you six weeks to get your accuracy down to twenty-seven yards, or you’re off the squadron.’4

He was only half-joking. On 617 Squadron, everything revolved around accuracy in bombing. Before they were allowed on ops, every new crew was required to carry out at least three six-bomb practice drops on the ranges at Wainfleet on the Wash in Lincolnshire. The crew’s accuracy was assessed and the results added to the Bombing Error Ladder kept by the Bombing Leader. Crews with the highest accuracy – and the results of even the most experienced crews were continually updated – were assigned the most ops and the most important roles on those ops, and those with poorer records would find themselves left out, or even transferred off the squadron altogether, if their results did not improve. Cheshire was relentless in raising standards, but he set himself the highest standards of all, and was universally admired and even loved by the men under his command. ‘He was a great man,’ Johnny Johnson says, ‘and the finest commander I served under.’5

* * *

In the autumn of 1943, during the continuing lull in ops that followed the disaster of Dortmund–Ems, 617 had been practising high-level bombing with new 12,000-pound ‘Blockbuster’ HC bombs – the equivalent of three 4,000-pound ‘cookies’ bolted together.

One of the squadron’s rear gunners, Tom Simpson, was lugging his Browning machine guns to the firing range one morning with 400 rounds of ammunition draped around his neck, when a ‘silver-haired, mature gentleman’ approached. A civilian on the base was an unusual sight, but the man seemed to know his way around. He asked if he could walk with Simpson and helped to carry one of the guns. After Simpson had installed the guns in the practice turret and fired off a few bursts himself, he noticed the stranger’s ‘deep blue eyes gleaming’ and asked, ‘Would you like to sit in here and have a little dab yourself?’

The man didn’t need a second invitation. Having watched him fire both guns singly, Simpson invited him to fire off the last hundred rounds using both guns together. After doing so, he was ‘trembling with excitement and pleasure’ as he climbed out of the turret. ‘That was really fantastic,’ he said. ‘I had no idea of the magnitude and firepower a rear gunner has at his disposal.’ Only later did Simpson realise that the silver-haired, mature gentleman was Barnes Wallis.6 When he mentioned the incident to Mick Martin, he told him that Wallis was developing even bigger and better bombs for the squadron. Within a few months they would all have the proof of that.

Barnes Wallis

Wallis, whose wife’s sister and brother-in-law had been killed by a German bomb in 1940, had already devised Upkeep – the ‘bouncing bomb’ used on the Dams raid. Forever innovative and forward-looking, he had never believed that carpet bombing could break German resolve, any more than the Blitz had broken Britain’s will to fight. Instead, he had argued from the start for precision bombing of high-value economic, military and infrastructure targets, and designed a series of weapons capable of doing so. He had been given the task of creating newer, ever more destructive weapons that could penetrate and destroy heavily fortified concrete bunkers and other targets, previously invulnerable to conventional attack.

A vegetarian non-smoker, Barnes Wallis came from a respectable middle-class background – his father was a doctor and his grandfather a priest – yet at sixteen years old, he had set his face against the advice of his parents and teachers and left school to take up an apprenticeship as an engineer. In later years, his daughter Mary attributed that decision to an experience when he was very young and his mother had taken him to a foundry to see the men and machinery at work. ‘The size, power, the noise of machinery in the light of the flames from the foundry furnace’ may have made a lasting impression on him.

Whatever the reasons, Wallis’s career path was set, though at first he showed more interest in the sea than in the air, training as a marine engineer, before being recruited by Vickers to work on airship design. An engineering genius, he worked as the chief designer on the R100 airship, ‘a perfect silver fish gliding through the air … a luxury liner compared with the sardine-tin passenger aircraft of today’. Having pioneered the geodetic system of construction in airships (more commonly called geodesic) – a latticework system of construction that produced a very light metal structure that nonetheless possessed great strength – he went on to apply it to military aircraft too, first using it on the airframe of the Wellington bomber. Despite his considerable achievements, he was a warm, humane and profoundly modest man. ‘We technical men like to keep in the background,’7 he said, and a friend and work colleague remarked that: ‘He would sooner talk about his garden than himself.’

Although he had designed aircraft, Wallis knew very little about bomb construction, but right from the outset of the war he resolved to put that right as quickly as possible. One of his early discoveries was that the explosive power of a bomb is proportional to the cube of the weight of the charge it carries, so that, for example, a 2,000-pound bomb would have eight times the impact of a bomb half its weight. He also learned that the pressure wave from an explosion is transmitted far more efficiently through the ground or through water than it is through air. Both of those discoveries were reflected in the design of the ‘Upkeep’, ‘Tallboy’ and ‘Grand Slam’ bombs he subsequently produced.

In addition to the new bombs Barnes Wallis was producing, 617 Squadron were now using a new and far more accurate bombsight. Shortly before Leonard Cheshire’s arrival, 617 had begun training with the sophisticated new SABS. Its only major drawback was that it required a long, straight and level run to the dropping point, reducing the pilots’ ability to make evasive manoeuvres and increasing their vulnerability to flak and fighter attack.

Wireless operator Larry Curtis always dreaded that vulnerable time, flying straight and level with the bomb-aimer in virtual control of the aircraft:

As long as you were busy, you never thought about anything except the job you were doing. But when it came to the bombing run, and to a great extent your duties were finished, it was then that you became aware that you were very vulnerable and people were actually trying to kill you. In the radio operator’s cabin there was a steel pole – some sort of support – and I used to hang on to it like grim death. I’ve always said if anyone could find that steel pole, they’d find my fingerprints embedded in it – and I’m not joking. It did come home very forcefully; I’m sure everyone would agree that was the time you dreaded. 8

There was no man on the squadron who did not feel fear at times, but, says one of the squadron’s wireless operators, ‘it was all about pushing fears to one side. I think if anyone said they were never afraid, I’d say they were either not there, or they’re lying. There was no possibility you couldn’t be scared at some points.’9

Even the squadron’s greatest heroes were not immune to fear. Wilfred Bickley, an air gunner who joined 617 at the same time as the great Leonard Cheshire, VC, once asked him, ‘Do you ever get scared?’

‘Of course I get scared,’ Cheshire said.

Bickley broke into a broad grin. ‘Thanks for that, you’ve made my day.’10

At a reunion after the war, Cheshire also said to one of his former men on 617 Squadron: ‘I could have been a pilot or at a pinch a navigator, but could never have done the other crew jobs; there was too much time to think, to be isolated, to dwell on what was going on around you. I never felt fear as a pilot, but as a passenger, I certainly felt it!’11

* * *

The use of the new SABS bombsights in training on the ranges at Wainfleet had led to a huge improvement in accuracy, but the first real chance to assess their effectiveness under operational conditions came in raids against Hitler’s new ‘V-weapons’. ‘V’ stood for Vergeltungswaffen (‘vengeance weapons’), and these ‘terror weapons’ were the Nazis’ chosen method of retaliation for the relentless Allied bombing of German cities. Lacking the heavy bombers and air superiority required to inflict similar damage on Britain, Hitler had authorised the development of three V-weapons: the V-1 ‘flying bombs’ – an early forerunner of modern-day Cruise missiles, christened ‘buzz-bombs’ or ‘doodlebugs’ by Londoners – the V-2 Feuerteufel (‘Fire Devil’) rocket, and the V-3 ‘Supergun’. Reinforced underground sites were being constructed in the Pas de Calais, in occupied France, where the weapons could be assembled and then launched against Britain. Most of the work was carried out by the forced labour of concentration camp inmates, PoWs, Germans rejected for military service and men and women from the Nazi-occupied countries. They were slave labourers, worked round the clock and fed near-starvation rations, and many did not survive.

Destruction of the plants where the V-1s were being manufactured and the ramps from which they were to be launched had become an increasingly urgent priority. 617’s aircrews were briefed about the sites and what they meant. ‘We were trying to obliterate them before they were even made.’

Intelligence on the German V-weapon sites came both from reports by French Resistance members of unusual building activity, and from RAF large-scale photographic reconnaissance missions, which covered the entire northern French coast for up to 50 kilometres inland. Sporadic attacks were launched by Main Force squadrons but inflicted only superficial damage.

The task of finding and eliminating the V-weapon sites was made harder by the camouflage used by the Germans – some nets covering buildings were ‘painted to look like roads and small buildings’.12 The wooded terrain in which most of the weapons were sited also hindered attacks, but the biggest problem was the poor visibility and persistent fogs that shrouded the Channel coast of Occupied France for many winter weeks.

On the night of 16/17 December, 617 Squadron joined the assault on Hitler’s vengeance weapons, with a raid on a site at Flixecourt, south of Abbeville, where they were led into battle for the first time by Leonard Cheshire. A system of markers was use to aid accuracy in navigation and bombing. Parachute markers that floated slowly down were used to mark both turning points on the route to the target and the target itself, and target indicators, burning in different colours, were also utilised. On this op, a Mosquito from Pathfinder Force – the specialist squadrons that carried out target marking for Main Force ops – was marking the target from high level using Oboe (the ground-controlled, blind-bombing system that directed a narrow radio beam towards the target). However, the target indicators it dropped were 350 yards from the centre of the target, and such was 617 Squadron’s accuracy with their new SABS – their average error was less than 100 yards – that, although they peppered the markers with their 12,000-pound bombs, none of them hit the target.

Although unsuccessful, the failure in target marking at Flixecourt did have positive consequences, for it served as the catalyst for Cheshire and his 617 Squadron crews to begin lobbying for a change in the marking system. Deeply frustrated by the failure of the raid, despite the phenomenal accuracy of their bombing, Mick Martin argued vehemently that it was pointless for the squadron to be dependent on markers dropped from height when flying missions that risked, and often cost, the lives of 617’s aircrews. Far better, he said, for himself or somebody else in the squadron to take on the responsibility of marking the target at low level, but at first ‘Nobody seemed to listen,’ one of his crewmates recalled, ‘and I think Mick got sick of volunteering and making his suggestions.’13

However, Leonard Cheshire may already have been thinking along similar lines, and he became an equally fervent advocate of low-level marking. The 5 Group commander, Air Vice Marshal Ralph Cochrane, lent his support to the idea, driven in part at least by his intense personal rivalry with Air Vice Marshal Don Bennett, the commander of 8 Group, which included the Pathfinder Force. Cochrane lobbied hard for a trial of the low-level system and also argued forcibly that ‘his’ 617 Squadron could mark and destroy targets that were beyond the capabilities of 8 Group and its Pathfinders. Cochrane’s lobbying eventually proved successful, but if it was to be anything more than a short-term experiment, 617 would have to back up his words with actions.

Attempts to follow up the Flixecourt raid with a series of further attacks on V-weapon sites that December were aborted because of bad weather and poor visibility, but such conditions were, of course, no deterrent to the construction of the unmanned V-1 flying bombs that would eventually strike London.

The squadron strength for the ongoing war against the V-weapon sites was boosted in January 1944 by the arrival of several new crews. Among them was one lead by an Irish-American pilot, christened Hubert Knilans but always known as Nick, and so inevitably nicknamed ‘Nicky Nylons’ by his crewmates (nylon stockings, obtainable only across the Atlantic, were a rare commodity during the war, and a welcome gift for women); his good looks and American accent made him a magnet for the English girls. He came from a farming family in Wisconsin, but in 1941 was drafted for US military service. He wanted to be a pilot, not a soldier, but knew that the USAAF required all pilots to have a college degree, so, without telling his parents, he packed a small bag and set off for Canada. He arrived there literally penniless, having spent his last ten cents on a bus ticket from Detroit to the border, but he was following such a well-trodden path that the Canadian immigration officer merely greeted him with ‘I suppose you’ve come to join the Air Force?’ and directed him to the RCAF recruiting office, where he signed on to train as a pilot.14

He soon developed a taste for the practical jokes that all aircrew seemed to share. In the depths of the bitter Canadian winter, Knilans and a friend would slip out of their barracks at night, sneak up on their comrades pacing up and down on guard duty and, at risk of being shot by trigger-happy or nervous ones, they then let fly with snowballs. The sudden shock caused some of the more nervous to drop their rifles in the snow, and one even collapsed as he whirled round to face his attacker.

After completing his flying training, he sailed for England with thousands of other recruits on board the liner Queen Elizabeth. So eager was Britain to receive these volunteers that the medical and other checks they went through were often rudimentary. One New Zealander boarding his ship passed ‘a friendly chap at the gangway asking him how he was as he passed by’.15 The ‘friendly chap’ turned out to be the medical officer giving each man boarding the ship his final medical examination!

After a bomber conversion course, Knilans joined 619 Squadron at Woodhall Spa in June 1943. He flew his first operational mission on the night of 24 July 1943 as Bomber Command launched the Battle of Hamburg, including the first-ever use of ‘Window’ – bundles of thin strips of aluminium foil now called ‘chaff’. Window was dropped in flight to disrupt enemy radar by reflecting the signal and turning their screens to blizzards of ‘snow’.

Informed in October 1943 that he was to be transferred to the USAAF, Knilans refused, insisting on remaining with 619 to complete his tour. His eagerness to fly almost cost him his life later that month when his aircraft was targeted by a night-fighter during a raid on Kassel. A stream of tracer shattered the mid-upper turret, temporarily blinding the gunner with shards of Perspex, and another burst fatally wounded the rear gunner, leaving the Lancaster defenceless. Both wings were also hit, but Knilans threw the aircraft into a vicious ‘corkscrew’ that shook off the fighter. It was a heart-stopping, gut-wrenching manoeuvre, especially for rear gunners who, facing backwards, were thrown upwards as if on an out-of-control rollercoaster as the Lancaster dived and then plunged back down as the pilot hauled on the controls to climb again.

Despite the damage to his aircraft, the loss of his gunners, and damage to one engine, Knilans insisted on pressing on to bomb the target, before sending some of his crew back to help the wounded gunner. ‘I knew that in an infantry attack, you could not stop to help a fallen comrade,’ he said. ‘You had to complete your charge first. Bomber Command called it “Press on, regardless”.’

Despite damage to his undercarriage, including a flat tyre on the port side, Knilans eventually made a safe landing back at Woodhall Spa, using brakes, throttles, rudders and stick as he battled to keep the aircraft on the runway. He then helped the ambulance crew to remove the blood-soaked body of his rear gunner from the rear turret. He had almost been cut in half by the cannon shells that killed him. The squadron doctor issued Knilans with two heavy-duty sleeping pills so that his sleep would not be disturbed by those horrific memories, but he gave them instead to the WAAF transport driver, a good friend of the dead gunner, who was overcome with grief and unable to drive.

Awarded the DSO for his courage, Knilans wore that medal ribbon on his uniform, but not the other British, Canadian and American medals to which he was entitled. ‘I thought it would antagonise others on the same squadron,’ he said, ‘or confirm their prejudices about bragging Yanks.’

Although he had pressed on to the target on that occasion, on another, while flying through a ‘box barrage’ from heavy anti-aircraft gun batteries over Berlin, with flak bursting all around them and fragments from near-misses rattling against the fuselage, his bomb-aimer told him, ‘Sorry Skip, the flare’s dropped into the clouds. We’ll have to go round again.’

‘You can still see the lousy flare,’ Knilans angrily replied. ‘Now drop the bombs!’ The bomb-aimer got the message, ‘saw’ the flare and dropped the bombs, and they then ‘departed in haste’.

Knilans was a popular figure on his squadron, even though he had made a deliberate decision not to become too closely involved with his crewmates. ‘I would have liked to have met their families, but I decided against it. If the crew members became too close to me, it would interfere with my life or death decisions concerning them. A kind welcome by their families would add to my mental burden. It could lead to my crew thinking of me as unfriendly, but it could lead to their lives being saved too.’

By January 1944, Knilans had decided:

I did not want to go on bombing civilian populations. There were few front-line soldiers and the flak-battery operators were women, young boys and old men. The cities were filled with workers, their wives and children … This type of bombing had weakened my reliance on my original ideal of restoring happiness to the children of Europe. Here I was going out and killing many of them on each bombing raid … It was an evil deed to drop bombs on them, I thought. It was a necessary evil, though, to overcome the greater evil of Nazism and Fascism.

However, keen to remain on ops, he volunteered for 617 Squadron, which instead bombed ‘only single factories, submarine pens and other military targets’, and persuaded his crew to join with him. Two other squadron leaders promptly put the wind up some of them by telling them that 617 was ‘a low-level flying suicide squadron’, but Knilans merely shrugged and told them that he wasn’t concerned about that, since ‘nobody had managed to live long enough to finish a tour’ on their present squadron either.

The RAF regarded a loss of around 5 per cent of the aircrews on each combat trip as acceptable and sustainable. After a quick mental calculation, Nick Knilans had ‘figured it out that by the end of a first tour of thirty trips, it would mean 150 per cent of the crews would be lost. Suicide or slow death, it did not make much difference at that stage of the war.’

Two other pilots and their crews from 619 Squadron, Bob Knights and Mac Hamilton, followed his lead, telling him that ‘they did not like bombing cities indiscriminately either’. It was a short move over to 617 Squadron, as it was in the process of transferring to Woodhall Spa, ensuring that Knilans could continue to enjoy the comforts of the Petwood Hotel Officers’ Mess: ‘the best damn foxhole I would ever find for shelter’.

Knilans and his crew were allocated Lancaster R-Roger as their regular aircraft while on 617 Squadron. The ground crew thought it should be called ‘The Jolly Roger’ and wanted to paint a scantily dressed pirate girl ‘wearing a skull and cross bones on her hat’, but Knilans refused. ‘I did not want a scantily clad girl or a humorous name painted on the aircraft assigned to me. This flying into combat night after night, to me, was not very funny. It was a cold-blooded battle to kill or be killed.’

Knilans did not lack a sense of humour, however, and ‘carried away one day with the exhilaration of flying at treetop level at 200 mph’, he could not resist buzzing the Petwood Hotel. ‘We roared over the roof two feet above the tiles. It must have shook from end to end.’ It was teatime and a WAAF was just carrying a tray of tea and cakes to the Station Commander’s table. ‘The sudden thunderous roar and rattle caused her to throw the tray into the air. It crashed beside the Group Captain, my Commanding Officer. He was not amused. Wingco Cheshire told me later that he had quite a time keeping me from being court-martialled by my irate CO.’

* * *

On Boxing Day 1943 the last great battle of the sea war ended with the sinking of the German battleship Scharnhorst, but in terms of the final outcome of the war, an event had taken place a month earlier that, though known to only a handful of people at the time, was to prove far more decisive. At the Tehran Conference of 28 November, Roosevelt and Churchill had at last agreed to meet Stalin’s constant demands that a second front should be opened in the land war against Germany, and the invasion of France, code-named Operation Overlord, was set to begin in six months’ time, in June 1944.

617 Squadron’s transfer to their new home, Woodhall Spa, took place in early January 1944. A former out-station of RAF Coningsby, it was now a permanent base in its own right for 617’s crews and their thirty-four Lancasters. If the new base’s prefab buildings were less solid than the brick-built facilities at Scampton and Coningsby, their new airfield at least had three concrete runways and thirty-six heavy-bomber hard-standings, with three hangars, a bomb dump on the northern edge of the airfield and the control tower on the south-eastern side. The roads crossing the Lincolnshire flatlands around the base were all but deserted – petrol was strictly rationed and few had any to spare – but the skies overhead were always busy with aircraft, black as rooks against the sky, though, unlike rooks, the aircraft usually left their roosts at sunset and returned to them at dawn.

Officers based at Woodhall Spa were billeted in some style in the Petwood Hotel, originally a furniture magnate’s mansion and built in a half-timbered mock-Tudor style with a massive oak front door, windows with leaded lights and acres of oak panelling. The grounds included majestic elms, rhododendron-lined avenues, manicured lawns, sunken gardens and a magnificent lily pond. There was also an outdoor swimming pool, tennis courts, a golf course, and even a cinema – The Kinema in the Woods, or ‘The Flicks in the Sticks’ as it was christened by 617’s irreverent crews – in a converted sports pavilion on the far side of the Petwood’s grounds. The most highly prized – and highly priced – seats were the front six rows, where you sat in deckchairs instead of conventional cinema seats. The Petwood’s beautiful grounds and timeless feel could almost have made the aircrews forget the war altogether, had ugly reality not intruded so often. As Nick Knilans remarked, ‘One day I would be strolling about in this idyllic setting with a friend and the next day he would be dead.’

Inside the hotel there was a high-ceilinged, wood-panelled room adapted for use as a bar, a billiard room and two lounge areas with roaring log fires, though other parts of the building were sealed off and the most valuable paintings and furniture removed – a wise precaution given the boisterous nature of most off-duty aircrews’ recreations.

The Petwood provided the aircrew with a comfortable base to escape the rigours of the war – a luxury the men of Bomber Command held dear. On a visit to one bomber base, the great American correspondent Martha Gellhorn described their preparations for an approaching operation:

A few talked, their voices rarely rising above a murmur, but most remained silent, withdrawing into themselves, writing letters, reading pulp novels, or staring into space. Though they were probably reading detective stories or any of the much-used third-rate books that are in their library, they seem to be studying. Because if you read hard enough, you can get away from yourself and everyone else and from thinking about the night ahead. 16

Cheshire himself almost became the squadron’s first casualty at Woodhall Spa while carrying out an air test on 13 January 1944. Just after take-off, he flew into a dense flock of plovers and hit several of the birds. One smashed through the cockpit windscreen, narrowly missing Cheshire, while another struck and injured the flight engineer who was the only other person on board. Cheshire made a low-level circuit and managed to land his damaged aircraft safely. 617 Squadron mythology claims that at least twenty plovers were on the menu at the Petwood Hotel that night!17

The thin Perspex of the canopy and the bomb-aimer’s ‘fish-bowl’ in the nose were very vulnerable. ‘The last thing you want as you are tearing down the runway at a hundred-plus and about to lift off is a flaming bird exploding through the canopy; for one thing it makes a hell of a bang, and sudden loud noises are not popular in an aircraft, especially in the middle of a take-off.’ If they did hit a bird, the bomb-aimer and the flight engineer were ‘liable to get a faceful of jagged bits of Perspex and a filthy mess of blood, guts and feathers to clear up’, said Gunner Chan Chandler.18 Bird-strikes were a serious problem and at Scampton, Coningsby and Woodhall Spa there were scarecrows, bird-scarers and regular shooting parties with half a dozen shotgun-toting aircrew touring the perimeter of the base in a van and shooting every bird they saw. ‘There were no rules about it being unsporting to shoot sitting birds – slaughter was the order of the day, and slaughter it was.’19

Members of 617 Squadron also relieved the boredom of noflying days with games and pranks that showcased their endless – if pointless – ingenuity. One much-prized skill was the ability to put a postage stamp, sticky side up, on top of a two-shilling piece and then flip the coin so that the stamp finished up stuck to the ceiling. Those with a good sense of balance could attempt to do a hand-stand, balance on their head, and in that position drink a pint of beer without spilling a drop. A trick with an even higher tariff required them to stand upright with a full pint on their forehead, slowly recline until they were flat on the floor and then get back to their feet, once more without spilling a drop of beer.

Team games included Mess Rugby, played with a stuffed forage cap for a ball and armchairs as additional opponents to be avoided while sprinting across the Mess. There was also the ascent of ‘Mount Everest’, which involved piling chairs one on top of each other with ‘the odd bod perched in them’. The ‘mountaineer’ would then climb the heap bare-footed and clutching a plateful of green jelly. When he reached the top of the stack, he placed his bare feet one at a time firmly in the jelly, and then, holding himself upside down, left the imprints of his bare feet on the ceiling. Once the stack of chairs had been removed, newcomers were left to ponder how on earth someone had managed to walk across the ceiling 15 feet above the floor.

Such mountaineering exploits did not always end well. One Canadian pilot on another squadron, Tommy Thompson, covered his bare foot with black ink, but, having successfully made his footprint on the ceiling, lost his balance, fell and broke his leg. He ‘played the role of wounded hero quite well’ in the Boston and Lincoln pubs, and never told those who bought him a drink why he was on crutches.

The Boston pubs were always packed with aircrew from the surrounding RAF bases, and for those without cars, the scramble to get aboard the last buses that all left from the Market Place at 10.15 every night was, said one airman, ‘a sight which had to be seen to be believed’. Most of them just drank beer, and it was ‘rather innocuous’ because, by government decree, beer was no more than 2 per cent alcohol – less than half pre-war strength – and, says Larry Curtis, ‘you had to drink an awful lot of it before you got merry.’ There were regular sessions in the Mess, but the aircrew also ‘really needed a place away from the station where we could go to forget about the war for a while; we had a lot to be grateful for in the English pub,’ Curtis says.20

While the officers were enjoying a life of relative luxury at the Petwood Hotel, the NCOs found they had been allocated some rather less salubrious accommodation: a row of Nissen huts and wooden huts erected just outside the airfield’s perimeter fence at the side of the B1192 road. Roofed with corrugated iron, they were bone-chillingly cold in winter. One of the NCOs recalled, ‘One of the things we had to be careful about, living in Nissen huts in England in the winter, was that if you put your hand against the wall or the roof, it stuck there [because it froze to the metal]. I’ve seen a few hands with palms left behind.’21 There was one other peril for crewmen living in the Nissen huts: the trees around them were home to a colony of woodpeckers that drove them mad and disturbed their sleep after night ops with their endless, dawn-to-dusk drilling into the trees with their beaks.

Amidst the camaraderie, the dangers and the tedium of RAF life, the war ground on, and as the Christmas festivities of 1943 faded from their memories, the men of 617 Squadron began to wonder just how long the fight would last.