Читать книгу Return of the Dambusters: What 617 Squadron Did Next - John Nichol - Страница 9

CHAPTER 1 The Dams

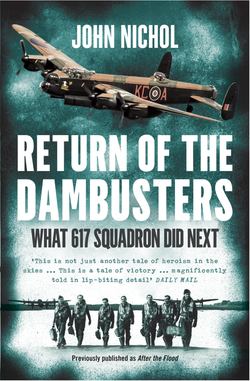

ОглавлениеA 617 Squadron Lancaster takes off for the iconic raid on the German dams

During the dark days of 1940, 1941 and the early part of 1942, when the British public had been forced to swallow an unremitting diet of blood, sweat, tears, toil and gloom, the RAF and Bomber Command had offered almost the only glimmers of hope. Despite the propaganda spin, while the evacuation of Dunkirk reduced the scale of disaster, it was a disaster nonetheless. British defeats by the Afrika Korps on the battlefields of North Africa and by the Japanese in the Far East – where the surrender at Singapore on 15 February 1942 was not just the greatest humiliation in Britain’s military history, but the moment from which the end of Empire could be said to have begun – continued the string of military reverses. Only in the air, where RAF Spitfires and Hurricanes had defeated the German bombers in the Battle of Britain and Bomber Command was relentlessly taking the war to Germany’s industrial cities, could Britain be said to be on the offensive.

In late 1942, the victory at the Second Battle of El Alamein ending on 3 November, and the lifting of the Siege of Malta on 11 December, coupled with new tactics at sea which were reducing, though not eliminating, the U-boat menace, suggested the military tide might finally be beginning to turn, but Britain’s commanders and people still looked to the air for proof that Germany was paying the price for its aggression.

A four-month bombing campaign against the cities of the Ruhr, aiming to pulverise and paralyse the heavy industries based there and so to disrupt Germany’s war production, had begun on 5 February 1943 with the bombing of Essen. But arguably, the most crucial targets were the string of dams in the hills flanking the Ruhr. They not only generated some of the power the heavy industries required, but also supplied drinking water to the population, pure water for steel-making and other industrial processes, and the water that fed the canal system on which the Ruhr depended, both to move raw materials to the factories and to carry finished products – aircraft parts, tanks, guns and munitions – away from them.

However, attempts by Main Force – as the squadrons carrying out mass bombing raids in Bomber Command were known – to attack small targets with the required accuracy had so far proved ineffective. Where the requirement was for saturation bombing over a broad area, Main Force could be brutally effective, as the thousand-bomber raid that devastated Cologne at the end of May 1942 had already demonstrated. But regular success in bombing individual targets – particularly if they were as difficult to access and as ferociously defended as the dams – had proved elusive.

Attacks by torpedo bombers like the Bristol Beaufort and the Fairey Swordfish were foiled by a lack of suitable weapons and by heavy steel anti-torpedo nets strung across the waters of the dams to protect them. A more radical solution was needed and the British engineering genius Barnes Wallis supplied it: the Upkeep ‘bouncing bomb’, a cylindrical weapon like a heavyweight depth charge, imparted with backspin to rotate it at 500 revs a minute. If dropped at the right height and distance from the dam, the bomb would skim like a pebble thrown across the surface of the water, bounce over the top of the torpedo nets and strike the dam wall. The backspin would then hold it against the face of the dam as it sank below the water before detonating to blow, it was hoped, the dam apart.

Having demonstrated the theoretical effectiveness of the bomb, all that was needed was a squadron of bomber crews capable of delivering it with sufficient accuracy. Since no such squadron existed, it became necessary to create one – 617 Squadron – and at the end of March 1943 recruitment of suitably skilled and experienced crews began under the leadership of Wing Commander Guy Penrose Gibson. He was a man with a glowing reputation as a fearless pilot, willing to take off in even the most marginal weather and attack the most heavily defended targets, whether capital ships or military or economic targets. The head of Bomber Command, Air Marshal Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris, later described Gibson as ‘the most full-out fighting pilot’ under his command and ‘as great a warrior as this island ever bred’.

Gibson had flown two full tours on bombers and one on night-fighters, completing the astonishing total of 172 sorties even before joining the new 617 Squadron. As a Squadron Leader and then a Wing Commander, he was as ruthless in screening his crews as he was aggressive in facing the enemy. That ruthlessness and an often abrasive and patrician manner, particularly with NCOs and ‘other ranks’, made him enemies – some of his ground crews nicknamed him ‘The Boy Emperor’ – but none could deny his courage or skill as a pilot, which were reflected by the Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar and Distinguished Service Order and Bar he had already been awarded prior to joining 617 Squadron.

Gibson was given a free hand in choosing men – all volunteers – from among crews who had already completed, or nearly completed, two tours of operations. The screening process continued even after they were chosen; Gibson posted two crews away from the squadron after deciding they were not up to the task and a third crew chose to leave after their navigator was also deemed unsatisfactory by Gibson. Intensive training of the remainder lasted for several weeks. In April 1943 alone, his crews completed over 1,000 flying hours, and at the end of that time Gibson reported that they could fly from pinpoint to pinpoint at low level in total darkness, fly over water at an altitude as low as 60 feet and carry out precision bombing with remarkable accuracy. They practised the raid itself using reservoirs in the Peak District and Rutland as substitutes for the Ruhr dams, and after a full-scale dress rehearsal on 14 May 1943, simulating the routes, topography and targets of the actual raid, Gibson pronounced it ‘completely successful’. The Dambusters – though no one yet called them that – were ready to take flight.

They had been training for six weeks in the utmost secrecy for a low-level bombing mission, but none of them knew the actual targets until the final briefing on the day the raid was to be launched. When they were told, every man in the room felt a stab of fear, ‘and if they said any different,’ says air gunner Fred Sutherland, ‘they’d be lying, because it looked like a real suicide run.’1

They were to target three dams – the Möhne, Eder and Sorpe – and their destruction would cause catastrophic flooding in the Ruhr valley and massive disruption to power generation, water supply, canal transport, agriculture, coal-mining, steel-making and arms manufacturing. If the raid successful.

* * *

On the nights she was not on duty, telephone operator Gwyn Johnson would often lie in bed, waiting in vain for sleep to come. She could sometimes hear the low, grumbling engine note of the bombers of 617 Squadron on their nearby base breaking the stillness of the night as, one by one, each pilot fired up his Lancaster’s four Rolls-Royce Merlin engines and began to taxi from the dispersal areas to the end of the runway. She could picture them waiting until a green light flashed from the runway controller’s caravan, when each pilot in turn pushed the throttles to the stops and his heavy-laden bomber began rumbling slowly down the runway. The noise swelled as one by one they lumbered into the air before finally disappearing into the night, the roar of the engines fading again to a sound like the distant rumble of thunder from a summer storm.

Not knowing whether her husband, Bomb Aimer Sergeant George ‘Johnny’ Johnson, was flying with them on any particular night, she often fell into an uneasy, fitful sleep, and a few hours later, as dawn approached, would wake again as she heard the aircraft return, no longer in a compact formation, but spread across the sky.

Hours later – if he had time – she might meet her husband for a snatched cup of tea in a cafe. He’d tell her if he’d been flying the night before and, though he gave her only the sketchiest details of the mission he’d flown, the look on his face was enough to tell her whether his comrades had returned safely or, more often than not, when one or more aircraft would have failed to return.

Yet, says Johnson, recalling those events seventy years later, ‘Gwyn had the same confidence as me that I would always come back. We both had an absolute belief we would survive.’2 Johnson, a country boy from a small Lincolnshire village with a habit of talking out of the side of his mouth as if all his conversation was ‘hush-hush’ and on a ‘need to know’ basis, was the bomb-aimer in American pilot Joe McCarthy’s crew.

Johnson and the rest of Joe McCarthy’s crew had all finished their thirty-op tour of duty with their previous squadron, 97, two months before the Dams raid, when they took part in a mass raid on the docks at St-Nazaire. ‘I could have called it a day after my thirty ops,’ Johnson says, ‘but I wanted to go on.’ After completing a tour, it was standard practice to be given a week’s leave before returning to duty, and Johnson and his fiancée, Gwyn, had arranged to get married on 3 April 1943, during his leave. They’d met when he was at the aircrew receiving centre at Babbacombe in 1941. He was walking down the street with his mate when they saw two young ladies walking towards them, and Johnson recalls coming up with ‘the corniest chat-up line. I said, “Are you going our way?” to which one of them replied, “That depends on which your way is!” That was Gwyn, that was the start and I never looked back!’

However, the week before the wedding, McCarthy, now the proud holder of a DFC, called the crew together and told them that Wing Commander Guy Gibson had asked him to join a special squadron being formed for a single operation. His crew at once volunteered to go with him for that one trip. The first thing most of the aircrew noticed when they joined 617 Squadron was how experienced most of their fellows were – ‘lots of gongs on chests’ as Johnny Johnson recalls. ‘With all this experience, we were obviously up for something special.’ But he had ‘no idea what 617 Squadron was going to do,’ he says, ‘not a clue,’ but when he wrote to Gwyn and told her he was going on another op, he added, ‘Don’t worry, it’s just one trip. I’ll be there for the wedding.’

Her reply was brief and to the point: ‘If you’re not there on April the third, don’t bother.’

He thought that it would still be fine until they arrived at the new squadron’s base, Scampton, where one of the first things they were told was that there would be no leave for anyone until after the operation. However, McCarthy then marched his entire crew into Guy Gibson’s office and told him, ‘We’ve just finished our first tour; we’re entitled to a week’s leave. My bomb-aimer’s supposed to be getting married on the third of April and he’s gonna get married on the third of April.’

The patrician Guy Gibson didn’t like being told what to do by anyone, least of all an NCO, and an American to boot, but in the end he granted them four days’ leave and Johnson’s wedding went ahead. Wives of married aircrew weren’t allowed to live on base, but Gwyn, a military telephone operator, was posted to Hemswell, eight miles from Scampton, and she and Johnny could meet in Lincoln on their days or evenings off. The last buses for Hemswell and Scampton both left Lincoln at nine o’clock, and Johnson invariably ended up on the Hemswell bus and then had to walk the eight miles back to Scampton. ‘I was one of the few who had a wife close by,’ he says, ‘and it was important for me to get away from the squadron atmosphere to “normal” married life. We never talked about the war and certainly not about any fears or concerns for the future. Our time together was time away from the war.’3

Johnny and Gwyn Johnson on their wedding day

* * *

Johnny Johnson and the rest of Joe McCarthy’s crew were one of nineteen Lancaster crews from 617 Squadron, a total of 133 airmen, who set out for Germany on that ‘one special op’ on the evening of 16 May 1943. At 9.28 that evening, a few minutes before the sun set over the airfield, the runway controller at RAF Scampton flashed a green Aldis lamp. The four Merlin engines of the Lancaster bomber, already lined up on the grass runway, roared up to maximum power and the aircraft thundered into the sky. 617 Squadron was on its way to Germany, and though none of the participants knew it at the time, into the history books.

Two of the nineteen crews turned back even before reaching the enemy coast; one accidentally losing their bomb over the North Sea, another with a flak-damaged radio. Another Lancaster was lost altogether after its pilot, Flight Lieutenant Bill Astell, who like his peers was flying at extreme low level, flew straight into an electricity pylon, killing himself and his entire crew. Sixteen aircraft now remained.

617 Squadron’s leader, Wing Commander Guy Gibson, led the remainder of the first wave to their first target, the Möhne dam. Each crew would have to drop their bomb with total precision, flying at a speed of 232 mph, exactly 60 feet above the surface of the dam. There was no margin of error – dropped from too low an altitude, any water splash might damage the aircraft; too high and the bomb might simply sink or shatter. If dropped too far away, it could sink before reaching the dam; too close, and it might bounce over the parapet.

While the remainder circled at the eastern end of the lake, Gibson began his bomb-run, swooping down over the forested hillside and roaring across the water towards the dam, its twin towers deeper black outlines against the darkness of the night sky. The Upkeep bomb was already spinning at 500 rpm, sending juddering vibrations through the whole aircraft – ‘like driving on a cobbled road’ as one crewman described it.4 Gibson had just fourteen seconds to adjust his height, track and speed before the moment of bomb-release. Alerted by the thunder of the Lancaster’s engines, the German gun-crews of the flak batteries sited in the two towers of the dam scrambled to their battle stations and opened fire. Not a trace of breeze ruffled the surface of the black water, which was so still that it reflected the streams of tracer from the anti-aircraft guns like a mirror, leading Gibson and the pilots making the first bomb-runs to believe there were not three but six anti-aircraft guns firing at them.

At 0.28 on the morning of 17 May 1943 Guy Gibson’s bomb-aimer released his bomb. Gibson banked round in time to see the yellow flash beneath the surface of the water and subsequent waterspout, but as the water splashed down and the smoke dispersed, it was clear that his bomb had failed to breach the dam. He then circled and called in the next pilot, John ‘Hoppy’ Hopgood, nonchalantly describing the task as ‘a piece of cake’. It was anything but. Hopgood’s Lancaster had already been hit by flak as they flew across Germany towards the target, wounding several of his crew and giving him a serious facial wound, but he flew on, pressing a handkerchief against the wound to staunch the flow of blood. Turning to evade the probing searchlight beams, he flew so low that he even passed beneath the high-tension cables of a power line stretching across a landscape as dark as the night sky above them.

As he made his bomb-run, Hopgood’s aircraft was again hit by flak and burst into flames. Although his bomb was released, it was dropped too close and bounced clean over the dam wall. Although it destroyed the electricity power station at its foot, sending a column of thick, black smoke high into the air, it did no damage to the dam itself. Hopgood managed to coax his stricken and burning aircraft up to 500 feet, giving his crew a slim chance of survival, but as he shouted ‘For Christ’s sake, get out!’5 the flames reached the main wing fuel tank, which exploded. Two crewmen did manage to bale out, and survived, to see out the war as PoWs. His badly wounded wireless operator also baled out, but his parachute did not open in time. Hopgood and the other three members of his crew were trapped in the aircraft as it crashed in flames, and all were killed instantly.

The twenty-five-year-old Australian pilot Harold ‘Mick’ Martin was next to make a bomb-run, with Gibson now bravely flying almost alongside him to distract the flak gunners and draw their fire. Martin’s bomb was released successfully, but two flak shells had struck a petrol tank in his starboard wing and, though it was empty of fuel and there was no explosion, the impact may have thrown their bomb off course. As Martin flew on between the stone towers of the dam, the bomb hit the water at an angle and bounced away to the left side of the dam, before detonating in the mud at the water’s edge. However, the force of the mud and water thrown up by the blast dislodged one of the flak guns on the southern tower from its mounting and the gun-crew of the battery in the northern tower were now also forced to change their red-hot gun-barrels.

In the lull in the firing, Melvin ‘Dinghy’ Young – so named after surviving two ditchings at sea – made his bomb-run. His Upkeep was released perfectly, bouncing in smooth parabolas along the surface of the water. It struck the exact centre of the dam and sank deep below the surface before detonating against the dam wall. The explosion sent up another huge waterspout, but once more it appeared to have failed to breach the dam.

The op looked to be heading for a disastrous failure, and the bouncing bombs’ designer, Barnes Wallis, waiting in the operations room back in England – the basement of a large house on the outskirts of Grantham – was almost beside himself as the succession of coded signals came through, announcing the failure of each bomb-run. He had tested his original concept by bouncing his daughter’s marbles across a tub of water, and had endured obstruction and ridicule before his ideas were accepted, but three bombs had already failed, and now the fourth bomb had also been dropped, once more without apparent effect.

Gibson now called up David Maltby, just twenty-three and, like Mick Martin, already the holder of the DFC and DSO. He was the fifth to make his approach, flying in at 60 feet above the water, with Gibson and Martin both acting as decoys to draw off some of the anti-aircraft fire. They even switched on their navigation lights to distract the flak-gunners, while their own forward gunners poured fire into the enemy positions, but although the raiders did not know this, all the anti-aircraft guns had now been put out of action and the gunners could only fire rifles at the Lancaster roaring across the lake towards them.

As he skimmed the surface of the water, his attention focused on the massive grey wall spanning the gap between the two towers, Maltby suddenly realised that the crest of the parapet was beginning to change shape. A crack had appeared, growing wider and deeper by the second as a section of masonry began to crumble and pieces of debris tumbled into the water. Close to his own bomb-release point, Maltby realised that Dinghy Young’s bomb had made a small breach in the dam which was already beginning to fail.

As a result, Maltby veered slightly to port to target a different section of the dam just as his bomb-aimer dropped the Upkeep bomb. It was released perfectly, bouncing four times, before striking the dam wall and then sinking below the surface right against the dam face. Moments after Maltby’s aircraft passed over the parapet, the bomb erupted in a huge column of water mixed with silt and fragments of rock.

It was still not clear at first if even this bomb had actually breached the dam, and, moments later, Barnes Wallis and the others listening in the operations room in England heard the terse radio signal: ‘Goner 78A’. ‘Goner’ meant a successful attack, ‘7’ signified an explosion in contact with the dam, ‘8’ no apparent breach, and ‘A’ showed the target was the Möhne dam.

However, as the debris from the waterspout spattered down, Maltby could see that the dam – its masonry fatally weakened by the repeated bomb-blasts – was now crumbling under the monstrous weight of water it held, and as the raiders watched, the breach gaped wider. The torrent pouring through the ever-growing gap, dragging the anti-torpedo nets with it, hastened the Möhne dam’s complete destruction. As it collapsed, widening into a breach almost 250 feet across, a wall of water began roaring down the valley, a tide of destruction sweeping away villages and towns in its path. Tragically, among the countless buildings destroyed were the wooden barrack blocks housing hundreds of East European women that the Nazis had compelled to work as forced labourers. Almost all of them were drowned, and they formed by far the largest part of the 1,249 people killed by the raid, one of the highest death tolls from a Bomber Command operation at that time.

Maltby sent a one-word radio transmission: the name of Gibson’s black Labrador dog, which told all those waiting in the operations room that the Möhne dam was no more. Air Marshal Arthur Harris, the head of Bomber Command, turned to Barnes Wallis, shook his hand and said, ‘Wallis, I didn’t believe a word you said when you came to see me. But now you could sell me a pink elephant.’6

Gibson told Maltby and Martin, who had both used their bombs and sustained flak damage, to turn for home, while he, old Etonian Henry Maudslay, the baby-faced Australian David Shannon – only twenty, but another pilot who was already the holder of the DSO and DFC – and yet another Australian, twenty-two-year-old Les Knight, who ‘never smoked, drank or chased girls’,7 making him practically unique in 617 Squadron on all three counts, flew on to attack the next target, the Eder dam. Thirteen storeys high, it was virtually unprotected by flak batteries, since the Germans believed that its position in a narrow, precipitous and twisting valley made it invulnerable to attack.

The approach was terrifying, a gut-wrenching plunge down the steep rocky walls of the valley to reach the surface of the lake, leaving just seven seconds to level out and adjust height, track and speed before releasing the bomb. Shannon and Maudslay made repeated aborted approaches to the dam before, at 01.39 that morning, Shannon’s bomb-aimer finally released the Upkeep bomb. Shannon’s angle of approach sent the bomb well to the right of the centre of the dam wall, but it detonated successfully and he was convinced that a small breach had been made.

Maudslay was next. Guy Gibson later described him pulling up sharply and then resuming his bomb-run, and other witnesses spoke of something projecting from the bottom of his aircraft, suggesting either flak damage or debris from a collision with the tops of the trees on the lake shore. Whatever the cause, Maudslay’s bomb was released so late that it struck the dam wall without touching the water and detonated immediately, just as Maudslay was overflying the parapet. The blast wave battered the aircraft, and although Maudslay managed to give the coded message that his bomb had been dropped, nothing more was heard from him or his crew. He attempted to nurse his crippled aircraft back to England but was shot down by flak batteries on the banks of the Rhine near the German-Dutch border. The Lancaster crashed in flames in a meadow, killing Maudslay and all the other members of his crew.

Knight now began his bomb-run. Like Shannon, he made his approach over the shoulder of a hill, then made a sharp turn to port, diving down to 60 feet above the water, counted down by his navigator who was watching the twin discs of light thrown onto the black water by spotlights fitted beneath the fuselage, waiting until they converged into a figure ‘8’ that showed they were at exactly the right height. Knight’s bomb – the third to be dropped, and the last one the first wave possessed – released perfectly, hit the dam wall and sank before detonating. The blast drilled a hole straight through the dam wall, marked at once by a ferocious jet of water bursting from the downstream face of the dam. A moment later the masonry above it crumbled and collapsed, causing a deep V-shaped breach that released a tsunami-like wall of 200 million tons of water.

The remaining aircraft of the second and third waves were now making for the third and last target of the night, the Sorpe dam. It was of different construction from the other two – a massive, sloping earth and clay mound with a thin concrete core, rather than a sheer masonry wall – making it a much less suitable target for Wallis’s bouncing bombs. Pilot Officer Joe McCarthy, a twenty-three-year-old New Yorker, was the only pilot of the second wave of five aircraft to reach the dam. Pilot Officer Geoff Rice had hit the sea near Vlieland, tearing his Upkeep bomb from its mounting and forcing him to abort the op and return to base. Like Astell, Flight Lieutenant Bob Barlow had collided with some electricity pylons, killing himself and all his crew, and Pilot Officer Vernon Byers had been hit by flak over the Dutch island of Texel. His aircraft crashed in flames, killing all seven men aboard.

New Zealander Les Munro was also hit by flak as he crossed the Dutch coast. As he reached his turning point approaching the island of Vlieland, he could see the breakers ahead and the sand dunes rising above the level of the sea, and gained a little height to clear them. He was, he recalled, flying ‘pretty low, about thirty or forty feet, and I had actually cleared the top of the dunes and was losing height on the other side when a line of tracer appeared on the port side and we were hit by one shell amidships. It cut all the communication and electrical systems and everything went dead. The flak was only momentary, we were past it in seconds, but one lucky or unlucky hit – lucky it didn’t kill anyone, or do any fatal damage to us or the aircraft, but unlucky that one shot ensured we couldn’t complete the op we’d trained so long for’ – had forced them to abort the op and turn for home.

For those who did make it to the target, the steep terrain and dangerous obstacles close to the Sorpe dam – tall trees on one side and a church steeple on the other – made it difficult to get low enough over the water for a successful bomb-drop. ‘All that bombing training we’d done,’ McCarthy’s bomb-aimer, Johnny Johnson, recalls, ‘we couldn’t use because, as the Sorpe had no towers, we had nothing to sight on. Also, it was so placed within the hills that you couldn’t make a head-on attack anyway. So we had to fly down one side of the hills, level out with the port outer engine over the dam itself so that we were just on the water side of the dam, and estimate as nearly as we could to the centre of the dam to drop the bomb. We weren’t spinning the bomb at all, it was an inert drop.’

McCarthy made no fewer than nine unsuccessful runs before Johnson, to the clear relief of the rest of the crew, was finally able to release their bomb. Had the dam been as well defended by flak batteries as the other dams, it would have been suicidal to make so many passes over the target, but at the Sorpe, the main threat was the precipitous, near-impossible terrain surrounding it. It was an accurate drop and the bomb detonated right at the centre of the dam, blasting a waterspout so high that water hit the rear gun turret of the Lancaster as it banked away, provoking a shocked cry of ‘God Almighty!’ from the rear gunner.8 McCarthy circled back but, although there was some damage to the top of the dam, there was no tell-tale rush of water that would have signalled a breach.

Two of the five aircraft from the third wave had already been shot down on their way to the target. Pilot Officer Lewis Burpee, whose pregnant wife was waiting for him at home, was hit by flak after straying too close to a heavily defended German night-fighter base and then hit the trees. His bomb detonated as the Lancaster hit the ground with a flash that his horrified comrades described as ‘a rising sun that lit up the landscape like day’.9 All seven members of the crew were killed instantly. Bill Ottley’s Lancaster also crashed in flames after being hit by flak near Hamm. Ottley and five of his crew were killed, but by a miracle, his rear gunner, Fred Tees, although severely burned and wounded by shrapnel, survived and became a prisoner of war.

Ground mist spreading along the river valleys as dawn approached was now making the task of identifying and then bombing their target even more difficult, and the third aircraft of the third wave, flown by Flight Sergeant Cyril Anderson, was eventually forced to abort the op and return to base without even sighting the target.

Flight Sergeant Ken Brown, leading an all-NCO crew, did find the Sorpe, and after dropping flares to illuminate the dam they succeeded in dropping their bomb, once more after nine unsuccessful runs. Like McCarthy’s, the Upkeep struck the dam wall accurately and also appeared to cause some crumbling of its crest, but the dam held.

Although the Sorpe still remained intact, for some reason the last aircraft, piloted by Bill Townsend, was directed to attack yet another dam, the Ennepe. Although he dropped his bomb, it bounced twice and then sank and detonated well short of the dam wall. Townsend’s was the last Lancaster to attack the dams, and consequently so late in turning for home that dawn was already beginning to break, making him a very visible target for the flak batteries. A superb pilot – on his way to the target he had dodged flak by flying along a forest firebreak below the level of the treetops – he was at such a low level as he crossed the Dutch coast and flew out over the North Sea that coastal gun batteries targeting him had the barrels of their guns depressed so far that shells were bouncing off the surface of the sea, and some actually bounced over the top of the aircraft.10

Although the Sorpe dam remained intact, the destruction of the Möhne and Eder dams had already ensured that Operation Chastise was a tremendous success, but it had been achieved at a terrible cost. Dinghy Young’s crew became the last of the night’s victims. An unusual character with an interest in yoga, who used to ‘spend much of his time during beer-drinking sessions, sitting cross-legged on tables with a tankard in his hand’,11 Young had reached the Dutch coast on his way back to base when he was shot down with the loss of all seven crew. His was the eighth aircraft to be lost that night, with a total of fifty-six crewmen killed or missing in action. Those waiting back in Lincolnshire for news, including Gwyn Johnson in her fitful sleep at her billet, faced a further anxious wait before the surviving Lancasters made it back. Townsend, the last to return, eventually touched down back at 617’s base at Scampton at a quarter past six that morning, almost nine hours after the first of the Dambusters had taken off.

As usual, Gwyn Johnson had heard the aircraft taking off before she went to sleep the previous night and had woken up again as they were coming back. For reasons of security – and for Gwyn’s peace of mind – Johnny hadn’t told her about the op before taking off, and he didn’t tell her he’d been part of the Dams raid at all until months after the event. ‘I didn’t really want to tell her I’d been on that particular op,’ he says, ‘as I suspected she might be annoyed I’d never mentioned it previously. Sure enough, when she did find out, she gave me an earful for not telling her in the first place!’

On the night of the raid, there had been ‘no sleep for anyone’ waiting back at Scampton as the hours ticked by. ‘Our hearts and minds were in those planes,’ said one of the WAAFs who were waiting to serve them a hot meal on their return. As the night wore on, twice they heard aircraft returning and rushed outside to greet crews who had been forced to turn back before reaching the target and were nursing their damaged aircraft home.

When they again heard engines in the far distance, the WAAFs were ordered back to the Sergeants’ Mess to start serving food to the first arrivals. They waited and waited, but no aircrew came in. Two hours later, their WAAF sergeant called them together to tell them the heartbreaking news that out of nineteen aircraft that had taken off that night, only eleven had returned, with the presumed loss of fifty-six lives. (In fact fifty-three men had died; the other three had been taken prisoner after baling out of their doomed aircraft.)

‘We all burst into tears. We looked around the Aircrews’ Mess. The tables we had so hopefully laid out for the safe return of our comrades looked empty and pathetic.’ Over the next few days, the squadron routine slowly reasserted itself and the pain of those losses began to diminish, but ‘things would never, ever be the same again’.12

The ground crews shared their sense of loss. ‘The ground crews didn’t get the recognition they deserved,’ one of 617’s aircrew says. ‘Without them we were nothing. They were out in rain, snow and sun, making sure the aircraft was always ready, always waiting for us to come back. And when one didn’t come back, it was their loss as much as anyone’s.’13

The aircrews of 617 felt the deaths of their comrades and friends as keenly as anyone, of course. ‘We had lost a lot of colleagues that night and there was a real sense of loss,’ Johnny Johnson says. ‘There were so many who didn’t make it home – just a mixture of skill and sheer luck that it didn’t happen to us as well.’ However, most of the aircrews were veterans of many previous ops and, if not on this scale, had experienced the loss of friends a number of times before and developed ways of coping. It wasn’t callousness, far from it, but with deaths occurring on almost every op they flew, men who dwelt on the deaths of comrades would not survive long themselves.

Losses of crewmates and friends were never discussed. ‘It just never came up,’ Johnny Johnson says:

though I did think about death when my roommate on 97 Squadron, Bernie May, was killed. We were on the same op together when his pilot overshot the runway on landing, went through a hedge and smashed the nose up. Bernie was still in the bomb-aimer’s position and was killed outright. By the time I got back, all his gear had been cleared away from our room. It affected me that one minute he was there, and the next minute, no trace of him. Just bad luck really, but you just had to go on and find another friend. That was how it was then.

‘The hardest part was writing to the relatives of those that didn’t make it,’ front gunner Fred Sutherland says. ‘Trying to write to a mother, and all you could say was how sorry you were and what a good friend their son had been to you.’

‘I’d lost friends and colleagues,’ Johnson adds:

but never thought it would happen to me, and I had total trust in Joe McCarthy. He was a big man – six feet six – with a big personality, but also big in ability. He was strong on the ground and in the air, which gave the rest of the crew a tremendous boost. Joe had a toy panda doll called Chuck-Chuck, and we had a picture of it painted on the front of all the aircraft we flew. Other than that, I didn’t believe in lucky charms – you made your own luck – but we had such confidence in Joe that it welded us together. We all gave him the best we could and trusted him with our lives and I never, ever, thought he’d not bring me back home.

McCarthy was a genial giant who had spent some of his youth working as a lifeguard at Coney Island. After three failed attempts to join the US Army Air Corps, he crossed the border and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force instead. He came to England in January 1942 and flew on operations to the Ruhr even before he’d completed his advanced training. He then joined 97 Squadron in September 1942, where Johnny Johnston became his bomb-aimer. Most of the ops they flew together were to the ironically named ‘Happy Valley’ – the Ruhr, which had such formidable air defences that bombing there was anything but a happy experience, and many of their fellow aircrews lost their lives.

McCarthy led a multinational crew. He was from the Bronx in New York, his navigator Don McLean, rear gunner Dave Rodger, and flight engineer Bill Radcliffe were all Canadians, and the three Englishmen – Johnny Johnson, Ron Batson, the mid-upper gunner, and Len Eaton, the wireless operator – were NCOs.

The mixture of rank and nationalities, Johnson says, ‘had no significance whatsoever to any of us. We were all on Christian-name terms, including Joe, and we all got on well. There was no stand-offishness, nothing to suggest any difference between any of us.’ By contrast their first meeting with their new commanding officer had been chilly, but Gibson was already known to get on much better with men of his own class and background than with ‘other ranks and colonials’. When Gibson was on 106 Squadron, Johnson says:

he was known as the ‘Arch-Bastard’ because of his strict discipline, and one thing he didn’t have was much of an ability to mix with the lower ranks; he wasn’t able to bring himself to talk with the NCOs, and certainly not with the ground crews. He was a little man and he was arrogant, bombastic, and a strict disciplinarian, but he was one of the most experienced bomber pilots in Bomber Command, so he had something to be bombastic about. He spoke to us all at briefings, but he never spoke to me on a one-to-one basis, or ever shook my hand, or even acknowledged me. But that’s just the way he was and he was a true leader in the operational sense, his courage at the dams showed that. 14

Gibson expected others to show no less courage and dedication, and he could be abrupt, even merciless, with those whom he decided had failed to meet his exacting standards. One of the reserve crews on the Dams raid, piloted by Yorkshireman Cyril Anderson, had been redirected to the Sorpe dam from their original target, but failed to find it. After searching for forty minutes, suffering a mechanical problem, and with dawn already beginning to lighten the eastern sky, Anderson aborted the op and returned to base with his Upkeep bomb still on board. Whether or not Anderson’s humble Yorkshire origins played a part in Gibson’s decision, he showed his displeasure by immediately posting Anderson and his crew back to 49 Squadron. In any event, the commander of that squadron did not share Gibson’s opinion of Anderson, and in fact recommended him for a commission as an officer shortly after he rejoined the squadron.15

However, others, even among the ‘other ranks’, found Gibson easier to deal with. He and his beer-drinking black Labrador – sadly run over outside Scampton the night before the Dams raid – were regulars in the Officers’ Mess, and wireless operator Larry Curtis, whose Black Country origins and rise from the ranks would not have made him a natural soulmate for Gibson, said of him: ‘I know some people said he was a bit hard, but I got on well with him … I found him hard but very just, you couldn’t ask any more than that. When it was time for business he was very businesslike, when it was time to relax, he relaxed with the best of them. I only regret I never had a chance to fly with him, because he was a wonderful pilot.’16 Gibson had demonstrated his skill and bravery as both a pilot and a leader many times, but the Dams raid was to be his crowning achievement.

Bomber Command C-in-C Arthur Harris had argued forcefully against the raid beforehand, describing the idea as ‘tripe of the wildest description’,17 but he and Air Vice Marshal The Honourable Ralph Cochrane, commander of 5 Group, of which 617 Squadron formed a part, had hurried from Grantham to Scampton to congratulate the returning heroes. For them, as for the government, the press and the nation, starved for so long of good news about the war, any reservations about the aircrew losses were swept away in the jubilation about the Dams raid’s success. 617 Squadron had shown Hitler and his Nazi hierarchy that the RAF could get through and destroy targets they had previously thought invulnerable. They had dealt a severe blow – albeit a short-term one, since the dams were repaired within months – to German arms production. They had forced the Germans to divert skilled workmen from constructing the Atlantic Wall to repair the dams, and that might well have a significant impact on the chances of success of an Allied invasion of France when it eventually came.

Even those successes paled beside the huge impact the raid had on the morale of the people of Britain, and on public opinion around the world, particularly that of our sometimes reluctant and grudging ally, the United States. ‘I don’t think we appreciated how important the raid was in that respect,’ Johnny Johnson says, ‘until we saw the papers the next morning, when it was plastered all over the headlines. There had been the victory at El Alamein a few months before and now this, and it was a big, big change in what had been a bloody awful war for us until then.’18

Ironically, Cochrane, a severe-looking man with a high forehead and a piercing stare, had warned the crews at their final briefing that the Dams raid might be ‘a secret until after the war. So don’t think that you are going to get your pictures in the papers.’19 Security before the raid had been so tight that one of the local barmaids in Lincoln was sent on holiday, not because she was suspected of treachery but because she had such a remarkable memory and such a keen interest in the aircrews that it was feared she might inadvertently say something that would compromise the op.

However, once the raid was over, any considerations of the need for secrecy were swept away like the dams, by the propaganda value of publicising the raid. The Dams raid chimed perfectly with the narrative created by British propagandists: the plucky but overwhelmingly outnumbered underdog fighting alone, and through expertise, ingenuity, courage and daring, breaching the defences of the monolithic enemy.

The Daily Telegraph exulted on its front page that ‘With one single blow, the RAF has precipitated what may prove to be the greatest industrial disaster yet inflicted on Germany in this war,’20 and the other newspapers were equally triumphant in tone. Guy Gibson was awarded a Victoria Cross for his leadership of the raid and more than half the surviving members of the squadron were also decorated, but Air Marshal Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris’s euphoria in the immediate aftermath of the raid soon gave way to pessimism. In a letter to the Assistant Chief of Air Staff he said he had ‘seen nothing … to show that the effort was worthwhile, except as a spectacular operation’,21 and although he often appeared unmoved by aircrew losses on Main Force – the major part of Bomber Command which carried out the near-nightly area bombing of German cities – he later remarked that missions where Victoria Crosses went along with high losses should not be repeated.

However, the damage to German industry and infrastructure was undoubtedly considerable. Thousands of acres of farmland and crops were buried by silt, and the land could not be tilled for several years. Food production, output from the coal mines and steel and arms manufacture were all badly hit. The destruction of power stations further reduced industrial output, and the disruption to water supplies caused by wrecked pumping stations and treatment plants not only deprived factories of water but left firemen in the industrial towns unable to extinguish the incendiaries dropped by RAF bombers. The destruction of 2,000 buildings in Dortmund was directly attributed to this.22

Nonetheless, when Barnes Wallis, who had also hurried to Scampton to add his congratulations, was told of the deaths of so many airmen, he cried. ‘I have killed all those young men,’ he said. His wife wrote to a friend the next day: ‘Poor B didn’t get home till 5 to 12 last night … and was awake till 2.30 this morning telling me all about it … He woke at six feeling absolutely awful; he’d killed so many people.’23 Although Guy Gibson and the others did their best to reassure him, according to his daughter Mary, Wallis lived with the thought of those deaths throughout the rest of his life.24

The Australian pilot Mick Martin’s opinion was that most of the casualties on the Dams raid had been caused because their navigation had been ‘a bit astray’ and, more importantly, because pilots didn’t keep below 200 feet on their way to the target. ‘Of course,’ said his rear gunner, who shared Martin’s views, ‘it’s easy to criticise when you’re sitting down at the back, arse about face, instead of up front where you see things rushing at you head-on, and even though it is moonlight, which can be almost as bright as day, there is a great risk of miscalculation of height, and objects such as power lines don’t show up like the Boston Stump’25 – the remarkably tall tower of St Botolph’s church in Boston, rising over 270 feet above the Lincolnshire fens, and visible from miles away.

The surviving aircrews washed away the bad memories of the night and toasted their success with a few beers. The Mess bars were reopened and drink was taken in considerable quantities. Some of the aircrews had ‘a mug of beer in each hand’, according to the Squadron Adjutant, Harry ‘Humph’ Humphries. ‘I could hardly keep my eyes open, yet these lads drank away as though they had just finished a good night’s sleep. The only thing that contradicted this was the number of red-rimmed eyes that could be seen peering into full beer mugs.’26 ‘The celebrations were in full swing,’ Les Munro says, ‘and I wondered if I really deserved to be part of it all. Should I be taking part in this when I hadn’t reached the target? All that training, preparation had been for nothing. But no one ever made any comment about us not getting to the target.’

The celebrations ended with a conga line of inebriated airmen visiting Station Commander Group Captain Charles Whitworth’s house and then departing again, having deprived the sleeping Whitworth of his pyjamas as a trophy. But while the crews had been celebrating or drowning their sorrows, Harry Humphries had the painful task as Squadron Adjutant of composing fifty-six telegrams and then fifty-six personal letters to wives and families, telling them that their loved ones would not be coming home.

Once the initial euphoria had passed, reactions within the squadron to the success of the Dams raid tended to be more muted. Some were elated but for most, ‘we were satisfied in doing the Dams raid,’ Johnson says, ‘but nothing more really. It was just another job we had to do. I had no sense of triumphalism or excitement, we realised what we had done, and were very satisfied, but that was all.’27 However, in a public demonstration of the importance of the raid to British morale, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth paid a visit to the squadron on 28 May 1943, with all the aircrews lined up, standing to attention and with their toecaps touching a white line that had been specially painted on the grass. They spent five hours there, though ‘naturally, of course, neither the King nor Queen visited the Sergeants’ Mess’.28

The gallantry awards for the raid – one Victoria Cross, five DSOs, fourteen DFCs, eleven DFMs and two Conspicuous Gallantry medals – were then awarded by the Queen in an investiture at Buckingham Palace on 22 June. Johnny Johnson hadn’t ‘the foggiest idea’ what the Queen said to him. ‘I was so bloody nervous. All I can remember saying is “Thank you, Ma’am” and that was it.’29 Although he was a teetotaller – ‘I couldn’t even stand the smell of beer,’ he says, ‘so I never went into the bars apart from a quick dash at lunchtime to pick up cigarettes’30 – he was in a minority of close to one on the squadron, and his fellows more than made up for him, with the investiture the trigger for a marathon booze-up. They were given a special carriage on the train taking them to London, where they had ‘a high old time’, and after chatting to the driver and his fireman during a stop at Grantham, Mick Martin’s crew made the next stage of the journey down to Peterborough on the footplate of the engine. They each threw a few shovelsful of coal into the firebox and took turns to operate the regulator under the supervision of the driver and ‘gave the old steam chugger full bore’. The driver offered to stand them a drink at any pub of their choice in London, and they duly obliged him at the appropriately named Coal Hole in the Strand.

The more well-to-do of the aircrews stayed at the Mayfair Hotel, while the less affluent settled for the Strand, and in the words of one of the Australians, ‘for twenty-four hours there was a real whoopee beat-up’.31 As a result none of them were looking at their best on the morning of the investiture. Mick Martin’s braces had disappeared somewhere along the line, but his resourceful crewmates ‘scrounged a couple of ties and trussed him up like a chicken, sufficient to get him onto the dais at Buckingham Palace, down the steps and off again’.

The squadron’s resourcefulness was also demonstrated by one of Mick Martin’s crewmen, Toby Foxlee, who, as petrol was strictly rationed, obtained a regular supply of fuel for his MG by ‘a reduction process’ which involved pouring high-octane aircraft fuel through respirator canisters he had scrounged; ‘the little MG certainly used to purr along pretty sweetly’.32

On the evening of the investiture, A. V. Roe, the manufacturers of the Lancaster, threw a lavish dinner party at the Hungaria restaurant in Regent Street for the ‘Damn [sic] Busters following their gallant effort on the Rhur [sic] Dams’33 – the budget for the dinner clearly didn’t extend to a proofreader for the menu! Given the austerity of wartime rationing, a menu including ‘Crabe Cocktail, Caneton Farci a l’Anglaise, Asperges Vertes, Sauce Hollandaise, and Fraises au Marasquin’, washed down with cocktails and ample quantities of 1929 Riesling, 1930 Burgundy and vintage port, was an astonishing banquet.

As the heroes of 617 Squadron celebrated their awards that night, Bomber Command’s war against Germany ploughed on with a raid by nearly 600 aircraft against the city of Mulheim, north of Düsseldorf. The city’s own records describe the accuracy of the bombing and the ferocity of the fires. Roads into and out of the area were cut and the only means of escape was on foot. The rescue services were overwhelmed, resulting in terrible destruction. Five hundred and seventy-eight people were killed and another 1,174 injured. Public buildings, schools, hospitals and churches were all hit. The German civilian population was paying a high price for Nazi aggression.34

Churchill’s War Cabinet were quick to use the success of the Dams raid in the propaganda war against the enemy, and some of 617’s aircrews were sent on publicity tours that spanned the globe, spreading the message about how good the RAF’s premier squadron was through the world’s press, radio stations and cinema newsreels. The main attraction was of course the leader of the raid, Guy Gibson, who was taken off ops, stood down as commander of the squadron, and sent on a near-permanent flag-waving tour, though before he left he managed to fit in a last trip to see ‘one of the local women, a nurse, with whom he had been involved while his wife was in London’.35 Gibson also ‘wrote’ (it is possible that Roald Dahl, working as an air attaché at the British Embassy in Washington, was the actual author) a series of articles, and a draft script for a movie of the Dams raid that director Howard Hawks was contemplating, then settled down to write his account of the Dams raid and his RAF career: Enemy Coast Ahead.

Mick Martin was by now widely recognised as the finest pilot on the squadron and had a wealth of operational experience behind him, but either his relatively lowly rank of Flight Lieutenant, requiring a double promotion to get him to the rank of Wing Commander – ‘it was considered not the done thing for him to jump two ranks’36 – or a belief among his superiors that he was a lax disciplinarian had counted against him – or perhaps the RAF ‘brass’ just didn’t want an Australian as CO. In any case, after just six weeks, he was replaced by Squadron Leader George Holden, who had taken over Guy Gibson’s crew following his departure. If Holden shared something of Gibson’s arrogance and his coolness towards NCOs, he lacked the former commander’s charisma and leadership ability, and was not generally popular with his men.

His reign as commander of 617 was not to prove a long one, and in the perhaps biased opinion of Mick Martin’s rear gunner, ‘somebody made a bad mistake’ in appointing Holden at all, since his knowledge of low flying was ‘practically nil’.37 Martin, by contrast, was ‘superb, a complete master of the low-flying technique’, and so dedicated that he continued to practise his skills every day. One new recruit to the squadron was given Martin’s formula for success at low level: ‘Don’t, if you can help it, fly over trees or haystacks, fly alongside them!’38 His bomb-aimer, Bob Hay, was also the Squadron Bombing Leader, charged with ensuring his peers achieved the highest possible degree of accuracy.

In this, he was encouraged by Air Vice Marshal Ralph Cochrane, who on one celebrated occasion even flew as bomb-aimer with Mick Martin’s crew on a practice bombing detail. Cochrane arrived ‘all spick and span in a white flying suit’, took the bomb-aimer’s post and achieved remarkable accuracy. The results were shown to the other crews, with the implicit message that if an unpractised bomb-aimer like Cochrane could achieve such results, the full-time men on 617 Squadron should be doing a lot better themselves.

While Martin was in temporary charge, his crew had put their enforced spare time to good use by creating a garden in front of ‘the Flights’ – the place where they spent their time before training flights or ops, often hanging around waiting for the weather to clear. Having found a pile of elm branches, they erected a rustic fence with an arch at the front and the squadron number at its apex, picked out in odd-shaped pieces of wood. They scavenged, dug up and, in cases of dire necessity, bought plants and shrubs, creating a peaceful haven. Sitting there in the sunshine, inhaling the scents of flowers and listening to the birdsong and the drowsy sound of bees, they could imagine themselves far from the war … until the spell was broken as the Merlin engines of one of the squadron’s Lancasters roared into life.

As the euphoria of the Dams raid faded, the remaining men of 617 and the new arrivals brought in to replace the crews lost on the raid settled down to a period of training which extended, almost unbroken, for four months. ‘There was quite a gap between ops after the dams,’ Fred Sutherland says, ‘though I must say, I wasn’t that bothered, and in no hurry to get back on ops.’ Not all of the replacements were as experienced as the original crews. When Larry Curtis first reported to his commander, Gibson looked him over and then said, ‘I see you haven’t got any decorations, which surprises me.’

‘The day after I joined, I was on operations,’ Curtis said, with a grin, ‘which surprised me!’39

Born at Wednesbury in 1921, Curtis joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve from Technical College in November 1939. After training as a wireless operator/air gunner, he was posted to 149 Squadron, flying Wellingtons, and took part in the attack on the German battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau at Brest. After completing thirty ops, Curtis was sent to a bomber training unit as a wireless instructor, but still flew on the first thousand-bomber raid to Cologne. Commissioned in January 1943, he converted to the Halifax and joined 158 Squadron. During a raid on Berlin in March 1943 his aircraft was hit by flak over the target and all four engines stopped. As the aircraft spiralled towards the ground, the crew were about to bale out, when one engine picked up and the pilot was then able to recover and start the remaining three. Having already completed two bomber tours, Curtis joined Mick Martin’s crew on 617 Squadron in July 1943 as one of the replacements for the men lost on the Dams raid.40

One of the main attractions for a lot of the aircrew joining 617 Squadron was the chance to fly low level. After flying at 10,000 to 15,000 feet on his previous ops, the thought of operating at 100 feet or even less was thrilling for Johnny Johnson. ‘I thought, Wahey! Before I had been sitting on top of those bloody clouds and you could see nothing until you got to the target and then all you saw was rubbish. So it was absolutely exhilarating, just lying there and watching the ground going Woooof! Woooof! Wooooof! underneath me!’ Against the regulations, he always took off and landed from his position in the nose. ‘I didn’t see the point of trying to stagger back and forwards to the normal position by the spar. So I could see the runway rushing beneath my nose every time we took off, and as we landed, the runway raced up to meet me – I loved that!’41 One of their practice routes was over the Spalding tulip fields, and Johnson remembers a guilty feeling as they flew over the fields at low level, leaving a snowstorm of multi-coloured, shredded blooms and petals in their wake, torn up by the slipstream.42

In some ways the tail gunners had the worst job, with the greatest amount of time to ponder their fate. One rear gunner found it:

a very lonely job, cold and lonely, stuck out at the back of the aircraft with no one to glance at for reassurance or a little comfort. The first op was the worst; the only person who knew what it would be like was the skipper, because he had been on one op before with another crew. And he wouldn’t tell us what it was going to be like; he didn’t want to put the wind up us. We were naive and quite happy to trust to luck. Oh, I was afraid, especially of what was to come, the unknown, but you just couldn’t show it.

The odds were stacked against us, we knew that at the time, knew that the losses were huge. It’s not a particularly nice thought, but once you were in that situation you just had to carry on and do the job you were trained for, and you just blotted out everything else. You ignored the flak, ignored the aircraft going down around you. What else could you do? In many ways you were stuck in the middle of that horror, those losses. You don’t ‘cope’ with it, do you? You just do it. 43

Having been specifically formed for that single op against the dams, it now appeared to pilots like Les ‘Happy’ Munro (also known as ‘Smiler’ – both nicknames were sarcastic, because he was famed for his dour demeanour) that ‘nobody knew what to do with us. There was a hiatus, a sense of frustration. What was 617 Squadron for? The powers that be couldn’t seem to make up their minds about what to do with this special squadron they’d created.’ Munro was a New Zealander, but had enlisted because of:

a general feeling that we were part of the British Empire, and had an allegiance to King and Country. We were really aware, through radio broadcasts and cinema newsreels, of what Britain was facing and what they were being subjected to: the air attacks, the Blitz. It was a sense of duty for most of us young men in New Zealand to fight for ‘the old country’ against the Nazis, but of course I had no idea at all of what would happen to me or what was to come: the devastation, the dangers, the losses I’d see and experience. Nor that seventy years on I’d still be talking about it!

‘Being on 617 meant that there could be quite a long gap between ops,’ another crewman says.

I remember going on leave and meeting friends from my engineers’ course who had nearly finished their thirty-op tour whilst I’d only done three or four. That’s when you began to understand how different 617 was. My friends said I was a ‘lucky bastard’ for being on 617 and not Main Force, and they were probably right – I wouldn’t have liked to be on MF from all the stories I heard and read afterwards. 44

617’s lack of ops led aircrew from 57 Squadron, also based at Scampton, to shower them with jibes and insults and give them the sardonic nickname ‘The One-op Squadron’. The men of 617 retaliated by ‘debagging many of the Fifty-Seven men in a scragging session in the Officers’ Mess’,45 but they also ruefully acknowledged their reputation in their own squadron song, which they sang to the tune of a hymn written in 1899, ‘Come and Join Our Happy Throng’:

The Möhne and Eder dams were standing in the Ruhr,

617 Squadron bombed them to the floor.

Since that operation the squadron’s been a flop,

And we’ve got the reputation of the squadron with one op.

Come and join us,

Come and join us,

Come and join our happy throng.

Selected for the squadron with the finest crews,

But the only thing they’re good for is drinking all the booze.

They’re not afraid of Jerry and they don’t care for the Wops,

Cos they only go to Boston to do their bloody ops.

Come and join us …

To all you budding aircrew who want to go to heaven,

Come join the forces of good old 617.

The Main Force go to Berlin and are fighting their way back,

But we only go to Wainfleet where there isn’t any flak.

Come and join us …

Come and join our happy throng. 46