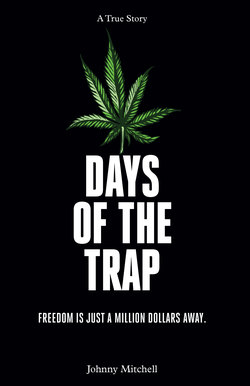

Читать книгу Days of the Trap - Johnny Mitchell - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Turf

ОглавлениеI’m shivering, the back of my palms itch and there’s a glean in my eye. I’m dope sick alright, and only one way I know to get well.

Fall of ’04 at the University of Oregon, and CJ and I are open for business. Ever the underachiever, I’d just managed to matriculate here by the skin of my nuts. Good thing I did — Eugene is a gold mine.

This isn’t a town, or a campus, or an institution of higher learning. This is a territory, a market — a faceless, bottomless organism that gobbles up the product and spits out cash.

Like any business, the dope game is structured like a two-lane highway running up the side of a pyramid — shit travels downhill while the money moves up it. CJ and I started in the bottom of the shit.

The name of the game is clientele. Any wannabe can go and cop a pack — all that matters is if he can move it.

Distribution is a fascinating thing. How does every product of earth move from raw material to factory floor to supplier and finally, get swallowed up by an invisible consumer? And what if that product is outlawed? How does one scale a business that isn’t allowed to exist? It all depends on the turf.

On the corners of west Baltimore and the favelas of Rio, crack and smack are sold in the open-air by crews of lookouts and runners, usually on consignment from older dealers who claim dominion over the corner and enforce it through economic power and violence. It is the most archaic, dangerous, and undemocratic way of selling drugs. In America, the open-air model is all but dead except for the most blighted areas, like the Tenderloin of San Francisco — places so densely populated and teeming with junkies that it makes sense for pushers to loiter at all hours of the day, as the traffic of fiends seeking out their fix is virtually nonstop.

The second model is the d-spot, or dope spot, invented in South Central during the crack explosion of the ’80s after Reagan turned the heat up on street dealing. Instead of exposing oneself to the elements, better to barricade the business indoors and have the customers come inside to score. Every ghetto in America during the ’80s and ’90s had at least one crack house on every block. The d-spot style of slinging is still employed in government housing all over America. Like church or 7-Eleven, it is a reliable landmark of every impoverished neighborhood, open twenty-four hours a day for the dope fiends’ convenience.

But by far the most civilized and ubiquitous means of distribution is curb-serving — or delivery. Technology and the advent of the cell phone opened a lane for middle-class dealers like CJ and I. No need to kill a man for his corner or stay up all night in a dirty trap house. Cell phones removed the need for brick-and-mortar institutions and democratized the buying and selling of narcotics. No more mafia-controlled monopolies, cheese lines, or bloody turf wars. The product is the advertisement — and may the best product win. Finally, a truly free market.

As it turns out, Eugene is the ideal place to get my dick wet. A major college campus is fertile turf for retail distribution. High density, trafficked with thousands of newly liberated young people — their pockets brimming with Mommy and Daddy and Uncle Sammy’s money —looking to get lost in a nihilistic fog of weed, booze, and fat white pussy.

CJ’s phone buzzes.

“It’s my professor again. Fucking guy is my best customer,” he says, pulling out two dub sacks from the shoebox below his bed. He grabs his skateboard and heads for the door.

“Hurry back so I can finish whooping your ass,” I say, pausing Madden on the PlayStation.

Our dorm room serves as the headquarters of our fledgling little empire, still a pipe-dream no doubt. Pre-paid phones chirping steadily, day and night we traverse campus, trading dope for dollars. Sweet Tea’s product is one helluva salesman, and it isn’t long before we have to start making weekly visits back to Portland for the re-up.

From the jump, our strategy has been to undercut.

“I want all the clientele,” I’d told CJ when we first set up shop. Like a sick junkie needs a soothing dose of heroin to ease his ills, so too do I need the reassuring feel of legal tender against my skin before I can rest well at night.

“You know how I can tell you’re gonna go far in this business?” CJ said to me one day after watching me count out a stack for the third time in a row. “You love money more than drugs.”

Indeed, a good drug dealer is far more addicted to the rush of quick cash than his customers are to his product. But it goes deeper than money alright — for the pusher, it’s the game itself that holds an irresistible allure. With each sale, each re-up, each pack that gets swallowed up by the earth, for a brief moment in time it makes him all-powerful — God-like, even — for he has stood up to the omnipotent power of society and all the resources aimed at stopping him, and triumphed. He is an outlaw, a free bird. No surprise that the public at large is privately enamored of the outlaw. The average citizen — condemned to life in a cubicle — admires him, in fact, for it is he who has taken a good look at the world and the way things are and politely declined. “I think I’ll do this my way,” he says.

But it ain’t all sweet — not by a long shot.

“There’s a problem,” CJ tells me one day after we’d finished off a pack.

Always a problem with him, but he’s got a crooked eye by nature. He lives in reality, and I’m a dreamer.

“We’re not making any money. We sell two ounces a week in twenty and forty bags, and we’re lucky if we pocket two hundred bucks a piece.”

He’s quite right. It’s the summer of ’05, and my plan to undercut worked — almost too well.

You see, Oregon has always been flooded with the cheapest, highest quality marijuana in the country. Only a bad motherfucker can turn a profit here. Two classes of dealers exist in this era: premium pushers who sell top-shelf, indoor-grown pot at the highest prices, and commercial pushers who deal in mass-produced outdoor pot to be sold at lower prices.

Trouble with our business model is, we’ve combined the two. We’re giving Sweet Tea $250 an ounce for drop dead, top-of-the-line indoor fire, but then turning around and retailing it at commercial prices. Now, our transaction rate to profit margin is laughably lopsided. In my lust to acquire clientele, I’d reduced our take to beer and sneaker money.

“It goes against the laws of economics, and logic,” CJ says. “We’ve got champagne and we’re giving it away like malt liquor.”

“I know, but now we’ve got the customers,” I say. “What we need to do now is level up. No more hand-to-hand sales. We become the dealers’ dealer and start wholesaling our packs.”

“We’re gonna need a bigger supply and a lower price — a lot lower. And we ain’t gonna get that from Sweet Tea.”

“Nope,” I say, shaking my head. We’ve outgrown the old pimp. Time to get to the source. “We need to find a grower.”