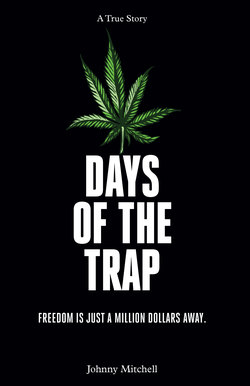

Читать книгу Days of the Trap - Johnny Mitchell - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Connect

Оглавление“Lift your shirts up for me please,” he says, the twang in his voice like an old guitar string.

They stare at us, unflinching — two hillbillies in overalls with shotguns resting over their shoulders — and suddenly, I’m reminded of the movie Deliverance. I glance at CJ. Surely, he looks more like a pig than me, right?

We’re hours away from anything, deep in the Klamath National Forest at the southernmost tip of the state. Down the hill and across a small valley, we see California. Beneath our feet is God’s country, the center of the Universe, the nucleus around which all life revolves. This is the northern tip of the Golden Triangle, the region where nine out of every ten pounds of domestic marijuana distributed throughout the nation originates.

We shrug, then lift up our shirts. No police wires — just pale, hairy beer bellies. The polite man nods and spits a gooey load of chew into the dirt.

“Whaddaya say, Ralph? These boys good?” he asks the officer leaning against his cruiser.

He nods.

“Followed them up from the five. They’re alone.”

These bumpkins mean business alright. We’d been directed to meet at a bar on the outskirts of Ashland, a small border town three hours south of Eugene off of Interstate 5. Almost shit my pants when a local pig in uniform was there to meet us.

“You must be Johnny and CJ,” he said, sidling up next to us at the bar. “Shot of whiskey,” he muttered to the barkeep. He tossed it down the hatch, wiped his mouth, then turned to us.

“Follow me.”

Making sure we didn’t have a tail, he proceeded to escort us out of town and deep into the backcountry, almost two hours up winding, unpaved roads that nearly ruined my 1990 Acura Legend.

Now, finally — we stood at the gates of Rome.

The polite man nods, smiling at us through tobacco-stained teeth.

“Very well, then. My name’s Kenny, and this here’s my brother Walt,” he beckons to the squat, pugnacious man standing next to him.

Walt nods and tips his John Deere hat, a chew the size of a golf ball jutting from his lower lip. There’s something frightening about him but I can’t quite make out what it is. Then I see it — he’s got a glass eye, sans pupil, sticking out of his head like a cue ball.

“This way, fellas,” he says.

After 1980, imported Colombian marijuana — which until then had supplied most of the American market — was put out to pasture by the Mexican cartels, who could grow it better and move it faster. Over the next thirty years, Mexican pot would itself die a slow death, this time at the hands of domestic growers like Kenny and Walt from Southern Oregon and Northern California. Not that the Mexicans gave up, they simply migrated north, setting up shop in the new Golden Triangle.

Now, an ideal climate and thousands of acres of public and private land was being exploited by growers of all stripes, with large criminal syndicates like the Sinaloa Cartel churning out thousands of pounds a year, down to the family-owned outfits producing a few hundred. This is the source, the supply — as high up the chain as a dealer could go. In the days of the Trap, it was every pusher’s dream to meet a grower, for just one of these connections could elevate him from hand-to-hand sales to weight-supplier overnight. It was like being admitted to an exclusive club, one with high membership dues — five thousand dollars to be exact — financed by CJ’s student loan check. That was the cost of the introduction to Kenny and Walt, brokered by a family friend of Kenny’s whom I’d met at a party in Eugene. It was winter of ’06, a year and a half after CJ and I began the search for a new supplier. We were living in a small apartment off campus and still nickel-and-diming Sweet Tea’s overpriced product.

“We’re gonna make this back tenfold,” I promised CJ. “This is the connect. No more small-timing. We’re about to become the man.”

The middleman, that is — the modern mercantilist tasked with moving goods from supplier to consumer. Only a handful of dealers in Eugene have connections with the growers in Southern Oregon. Every week, they make the drive south on I-5 and return north the same day with their trunks loaded. This return trip north is where the arbitrage happens, where prison time is risked, and where the real money is made. It’s time to start making real money.

We follow Kenny through a passage of trees and down a steep trail toward an old barn sitting at the base of the property. We pass a burnt-out Volkswagen bug parked on the side of the trail, so old it seems like a natural feature of the landscape.

“Take no offense at the security measures,” Kenny says. “Standard procedure.”

Walt flanks us from the rear, his shotgun at the ready, as though CJ and I are court martialed soldiers being paraded to the gallows.

“We’ve had some issues lately,” Kenny says. “Trusted friends who broke the code, chose to work for the other side.”

We hear a helicopter flying low in the distance.

“Feds,” he mutters, not bothering to look up.

“Plus, the Spics… ever since they come north from Sinaloa to set up grows, this area’s been hot. A few of those bastards even tried robbing us, but — I s’pose that’s the beauty of owning all this land,” he pauses, gazing out over the expanse of the countryside. “Easy to make a fellow disappear.”

He spits tobacco juice into the dirt and glances over at Walt, who grins for the first time.

I should’ve been frightened, but instead I just got more excited, like Karen in “Goodfellas” after seeing Henry Hill pistol whip her neighbor — a real whore for the rush. Besides, a man serious enough to kill is a man serious enough to do business with, and we’re in no position to take the moral high ground — not after two years of scaping by selling twenty-dollar pops.

We reach the barn, which looks ready to fall over any minute. Kenny flips a switch and the lights come on, revealing the reason for our visit. Hanging end to end from the ceiling are rows of fully mature, fifteen-foot-high weed plants with buds the size of cow dung sagging off of them.

“Harvest came early this year,” Kenny says, touching one of the plants lovingly. “Reckon we’ll get close to five hundred pounds once it’s all finished drying.”

“We’ll take it,” I say, only half kidding.

“Works for me,” he smiles. “I can sell these in Ashland for three grand all day, but for friends of Chris, I can go as low as, say, twenty-eight?”

“What are you, nuts?” CJ blurts out. “We could pay three thousand in Eugene and save ourselves the trip.”

The sack on this guy! He fancies himself a regular Tony Montana, negotiating with Sosa at his Bolivian hacienda.

“You want the merchandise to move fast, right?” CJ continues. “It’s better for everyone that way. But things aren’t how they used to be, ya know? Nowadays, everyone and their mother is sitting on weight. Plus, we’re the ones who gotta drive that shit up the interstate — that puts us at risk.”

Kenny smirks, impressed by the audacity. CJ, that motherfucker — he’s always found a way to get what he wants. He’s likeable and well-respected, and he’s got an intangible air of authority that draws people to him — qualities I don’t possess. Indeed, I can’t do this without him.

Kenny turns to look at his brother Walt, whose glass eye is twitching excitedly. He nods.

“Well,” Kenny says, looking back at us. “I reckon we can work something out.”

We wave goodbye now as I pull the Acura out of the driveway and proceed down the mountainside with the cop car trailing behind us.

At $2,300 a pound for top-quality commercial product, we can’t lose. We’ll become the dealers’ dealers’ dealer. It was that simple — just one little favor on behalf of the Universe, and now things will never be the same.

“Just one problem,” I say to CJ as we lumber down the bumpy dirt road. “Where are we gonna get an extra thirteen grand?”

“Not sure yet. I didn’t think that far ahead.”

Kenny and Walt had agreed to a sale price of $2,300 per pound, but on the condition that we buy ten pounds or more at a time. After all our scrimping and saving, CJ and I had only $10,000 in the operating account, leaving us well short of the $23,000 needed for the first purchase. They’d told us to return in three weeks, after the weed had been dried and trimmed and ready to move.

There’s no time to waste. Growers like Kenny and Walt have wholesalers driving in from all over the country to pick up merchandise. I’d even heard of dealers from out-of-state descending onto the Triangle during harvest season and buying up a grower’s entire yield in one trip. In the days of the Trap, when the supply of marijuana on the market was still finite — once a grower sold out of his stock — it meant just that, no mas . Then, his wholesalers would be left scrambling to find other growers. After all, a dope dealer ain’t much good to nobody without any dope to sell.

“I’ve got an idea,” I say to CJ, though I don’t speak it aloud. It’s the only thing that comes to mind for a pusher in need of a quick cash injection. The old-fashioned way. The ski mask way.