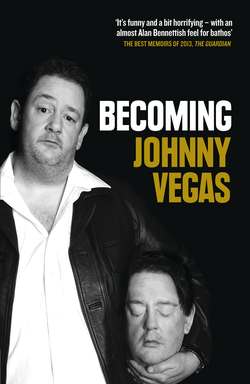

Читать книгу Becoming Johnny Vegas - Johnny Vegas - Страница 8

2. THE WHITE FATHER

ОглавлениеI made a decision at the age of ten that I truly believe changed everything, for ever. If you think I’m being dramatic, just ask yourself, did you leave home and loved ones at the age of eleven to go and train to become a priest?

No, thought not.

If you did, or if you experienced something even more detrimental, then I’m sorry for lecturing. I just need to make it clear that this book really begins with the planting of the seed of Johnny Vegas.

I should understand Johnny better than anyone: I created him, for fuck’s sake. Or so I thought. But in fact he was never a character. He was a stockpile of subconscious anger. He was the Midas touch to transform everything that might otherwise have crushed me.

Something had to trigger it. The subconscious is like a shit safari park on a rainy day: you need something big to come along to tempt the beast out and make it play. That’s why my story only really starts at the age of 10 – not at the very beginning, but in 1980.

Everything up to that point was more of a hugely contented false start. But it was from around this time that my feeling of displacement really kicked in – the genesis of what would prove to be an odd lifetime’s out-of-body experience. It sounds daft, I know, but the more I retreated inwards, the stronger the feeling of being alienated from myself would become. And the more at odds I’d feel with life’s expectations of me.

As a kid, I’d always said that I was going to be a priest when I grew up, but in truth I had never given it much serious thought. I reckon it was down to the positive reaction I’d get from people when I told them that I wanted to go into the Church as a career, or that I had ‘a calling’, as most believers referred to it.

I’d always felt a little guilty that God had never actually spoken to me directly and asked me to join his team. (Although I’d later learn that presuming an intimate acquaintance with the big man’s intentions was a necessary tool for keeping control within a seminary.) Still, as I grew older I kept saying it, and I remember enjoying the response it would get. You could hold a room full of grown-ups enthralled with talk of becoming a priest, or even maybe a White Father? No, I’m not sure what a White Father is, either, but I think they’re some sort of missionary – and to the good people of our parish, that ambition seemed even more impressive.

A White Father once came and did a sermon in our church. It was pure fire and brimstone stuff. He ranted from the pulpit about how everyone was in very real danger of going to hell – ‘Everyone!’ If St Austin’s had come equipped with a Tudor priest hole then Canon Tickle (only in unfortunate name, not by nature) would’ve been hurling women and children out of the way to get in it. When this guy got up a head of steam, you’d be forgiven for thinking the Pope himself was capable of shoplifting an oven-ready turkey – ‘That’s why John Paul’s gone to Iceland!’

I mean it. It was the Spinal Tap all the way up to 11, the Enola Gay, the head-popping-out-of-the-boat bit in Jaws, the ‘Let’s get rrrrready to rrrrrumble’, the Godzilla, the Star Wars Death Star, the space shuttle Challenger, the Wall Street Crash, the Hanna Barbera ‘Captain CAAAAAAYAYAYAYAAAAVEMAN!’, the first lesbian kiss on Brookside, the Mount St Helens eruption mother of all kick-ass sermons.

‘Stop right now!’ he screamed at the top of his lungs. ‘What are you actually thinking about right now? WHAT ARE YOU THINKING ABOUT!? And don’t lie ... because HE knows!’

I remember my mum, ashen-faced, telling me afterwards that she was doing her maths on the housekeeping and couldn’t remember whether or not she’d paid the pop man (we used to have it delivered, even after the daft rumour – probably spread by Soda Stream ponces – that staff used to pee in the vats at the Barton’s Pop Christmas party). Fizzy drinks were a luxury never denied us, no matter how tight money got. I think because our pop man wasn’t a faceless corporation, I liked him because he looked like Billy Joel from the Piano Man album cover. I’d imagine him playing a small Bontempi organ in his cab on quiet days and writing songs about all the discontented housewives he delivered dandelion and burdock to.

Anyway, in the middle of Mum balancing her books, this furious force of ecclesiastical nature condemned us all to eternal damnation. Had it been him in Footloose, instead of John Lithgow, he’d have broken Kevin Bacon’s legs with his own ghetto-blaster in the opening credits, before pouring quick-setting cement in his ears.

We were used to our local priest’s ‘softly, softly’ approach. But this White Bull in our chaste little china shop was promising us now’t but the fires of hell. There was no carrot at the end of his schtick. According to him, none of us would ever be good enough for heaven – even his own soul was in constant jeopardy. And yet, rather than scare me, he left a great impression. It was the first time I’d seen someone in a pulpit and thought, ‘If he’s that bothered, then he must be on to something.’

It didn’t just feel like he was going through the motions: ‘Let’s get this over with as quickly as possible so you can make the pub, or get yer roasties on!’ The grown-ups were getting it in the neck just as much as us young offenders. Unilateral guilt! Like a controversial but brilliant stand-up he was both shocking and mesmerising, with 100 per cent conviction in what he said. Imagine Sam Kinison in a white cassock and you’re still not quite there. He wasn’t coaxing the crowd, he was tearing ’em apart with his zealous conviction, forcing them to question the pious comfort zone they’d previously taken for granted.

But still, it wasn’t enough to make me take my own self-proclaimed vocation seriously, even though back then in St Helens religion was a massive part of our lives.

We got stick – sometimes at school, but mainly at our local youth club – for going to church. We were called ‘God squadders’, and the fact that my dad wore a crucifix openly around his neck made for even more grief. We even had to go to BENEDICTION. It wasn’t even a proper mass! I understand it’s about the veneration of the host, the body of Christ, but come on! When you’re young and in the middle of a big game of three pops in ... it felt like Lineker being dragged off the pitch by that turnip at the European Championships when my dad announced it was time to go to Benediction.

Lay-kids understood that Sundays involved some form of commitment as a God-botherer. Even glueys sometimes attended midnight mass – pissed, more probably tripping, but present at least. But nobody – no other kids, not even the majority of parishioners – went to Benediction. It was God’s way of screening for any potential Ned Flanders.

I actually liked us being a church-going family. There was a real sense of community. It had all the ambition of the middle classes, but with a god that didn’t abandon you at the first sign of a fiscal fuck-up. You were encouraged to love thy neighbour, not block their extension because you didn’t want your garden overseen.

There was strength to be drawn from faith, which I witnessed first-hand through my parents. The death of my nan, Mary, had a devastating effect on my mum. It’s an awful thing to see the heart of the family suddenly start to falter as Nan’s had. Mum was always the pragmatist who soldiered on no matter what, but for months afterwards the fight had gone, there was no wind in her sails, and she just appeared to be drifting aimlessly from day to day. Grief, depression, apathy, call it what you will, it’s agonising watching someone you love drowning in sadness but not having the strength of will to come up for air.

Every week, she would sit in church after mass staring into space, or sobbing, head in hands, as we looked on helplessly, ’till Dad ushered us outside. She had things to say to God, to her deceased mum, things she perhaps could not articulate to anybody else. When the fog eventually lifted, Mum would always attribute her emotional survival to her faith. That was what saw her through her darkest hours.

When Dad was made unemployed and every penny coming into the house mattered (although my parents did their best to shield us from this fact), it was his faith that stopped the pride-crushing struggle to make ends meet from getting the better of him. One hot summer’s day, when he’d dragged a huge chunk of scrap metal for what felt like miles on the back of a homemade trolley Uncle Joe had built – taking me along for company despite the fact that all I did was obsess over the ice cream he’d promised me from the profits – I could see the soul-sapping anguish as we got to the scrap-metal yard, only to find it was shut.

It was the point where most folk would be forgiven for quitting, for ranting, cursing and shaking their fist at the sky shouting, ‘Why me, eh, why? What more can I do to do right by those I care for? How much more do you need me to suffer before you’ve proved your point, eh?’ That’s definitely my default setting. But as my dad hung his head in what I thought was surrender, he was actually allowing himself a little prayer time. And when he eventually looked up, I could see his cheery determination was still intact, despite my stupid determination to point out the blatantly obvious.

‘It’s shut, Dad!’

‘I know.’

‘So what are we going to do?’

‘Well, I’m not carting it home, that’s for certain.’

‘So you’re just gonna leave it here?’

‘I am.’

‘But won’t someone else cash it in?’

‘Most likely, but who’s to say their needs won’t be greater than ours, eh?’

‘So, no ice cream?’

‘No, not today, kiddo.’

‘Bit of a wasted trip, then?’

‘Do you see that hill over there?’

And Dad walked me home via a massive detour telling story after story about him, my uncles and my aunties growing up. It turned into one of my fondest memories ever, and we still laugh about it to this day whenever we pass that way in the car. It was Dad’s faith that turned the day around, so why wouldn’t I grow up hoping that I’d inherit that same peace and inner strength?

True, a lot of religion was dogma at that stage, but I presumed faith would come through maturity, like a kind of theological puberty, and that one day the once barren landscape of questions would be full of fluffy answers to all of Life’s great mysteries, trials and tribulations sprouting up all over the place.

Making your first Holy Communion was a really big deal. It was taken for granted that I’d follow my brothers in becoming an altar boy afterwards. Which I did. And there’s no denying there were definite perks to the job.

For starters, you got out of school assembly to serve at morning masses and feast days. It was a free pass to wag off school with the added bonus of spiritual kudos, but it came at a cost. The position tended to carry more weight with the adults as eight-year-old lasses didn’t tend to dig altar boys. Any dormant uniform fetishes at that point would’ve been limited to fire-men, policemen, cowboys, astronauts, and maybe the occasional train driver: your basic run-of-the-mill fancy dress stalwarts and stuff of naive junior-school-career fantasies. There were no Pink Ladies, and we sure as shit weren’t no T-Birds. No room for wanna-be young nun equivalents to ‘dig’ where we were coming from.

There were some blokes well into their autumn years still trapped in time as altar ‘men’. They wore red under-cassocks as opposed to our black ones. They’d earned their position in their own quiet way, and deserved our respect, yet they felt more like a cautionary tale instead of aspirational figures – like kids held back at school year after year, until the only job they were capable of was caretaker.

So why do it? Yes, the hours were good, and yes, it meant we got a head start on racking up brownie points with old St Peter sitting up there at those blessed Pearly Gates, but the potential payday from a well-served funeral service was even better!

It’s an unpleasant truth to confess, especially to those of you who’ve buried someone dear via a Catholic service, but funerals were a big potential ‘Ker-ching!’ payday to angelic-looking wee parasites like Simon and me. The passing of a loved one, the distraught anguish, the sombre acceptance of the fragility of human existence, it was money in the bank.

Just as it was for the funeral directors who did this stuff day in, day out, and even the priests who, at times, sounded like they were reading out a shopping list as opposed to the recently deceased’s best qualities, death – or at least the spiritual task of delivering some poor soul unto the hands of their beloved maker – was run-of-the-mill stuff to us. It was a job!

And like any job you had to find the fun in it, whilst still projecting a sense of public dignity for those genuine mourners ‘… gathered here amongst us’. Flashing the reflected sunlight off the big cross we held was a favourite. If you were bold, you might then swish it briefly across the priest’s eyes as he was reading, but Simon was a bugger for highlighting the priest’s genitals – shining a light on his unholy of holys, and it never failed to get me giggling.

Dimon was the grand master of subtle mischief and could set me off so easily. Too much incense on the charcoal was his favourite: the altar would end up looking more like Top of the Pops. And you could sense he was smiling, even when looking straight ahead.

Remember that worst case of giggles you ever had as a kid? Someone sets you off and the severity of the situation just makes it worse, and makes the laugh even harder the more you try to bury it? Imagine that when you’re working the funeral of someone with a grieving family who’s hard as bloody nails, and you know you’ve caught the eye of a nutter sitting at the end of the front bench ...

If Dimon set me off, I’d have no option but to focus on my feet, hold my eyes open as long as possible without blinking till they’d water, and, whilst working the sniggering shudder in my shoulders into the routine as respectful sobbing, hold my head up at just the right moment to let the light catch a false tear running down my cheek in profile. Let me tell you, the young Ricky Schroder bawling his eyes out at the end of The Champ? That kid had nothing on me!

‘It feels forced, Ricky daaahling. Remember, keep it minimal, less is more!’

It sounds utterly disrespectful I know, but messing around with your back to the congregation, I reckon, actually gave me enough guilt to achieve genuine sorrow throughout the final procession out of church. And then a quick sniff of the altar wine to take the edge off the agonising wait to see if the funeral director had any tips to pass on courtesy of the grieving family. I wasn’t on pocket money like some other kids my age, so £1 or £2 was a small fortune.

There were also the rare days when you got a free pass to piss yourself laughing. Like when the priest dropped the burning charcoal on the new altar carpet, and tried, in a blind panic, to pick it up with his bare hands. It was definitely swearing, but edited like you’d see in an in-flight movie. He started off unintentionally shouting but managed to swallow the end of each curse, kind of like a stroke victim with Tourette’s: ‘FUrrrgh, SHIheeaah, WANhugh!’

The inappropriate fun we had might possibly have helped blindside me to the extent of the commitment required from anyone genuinely wanting to enter into the priesthood. The sacrifices required simply didn’t seem all that daunting at the time.

I remember my dad taking me aside after I’d yet again announced I was going to be a priest and saying, ‘Are you serious about the priesthood – about following your vocation?’ I had no idea what a vocation was. To be honest, I was probably as serious as I’d been about joining the Rebel Alliance after seeing Star Wars. In fact, I remember thinking Jedi Knights were basically kick-ass priests, but with swords. With a typical 10-year-old’s disregard for the implications of my answer I simply said, ‘Yes’ and gave no more thought to the wheels that simple little word had set in motion.

My decision to go into the seminary was certainly tough on my family. I knew money was tight, but I now realise the boarding fees must have been a massive burden on my mum and dad. The diocese used to decide what they thought families could afford and, as a result, my parents had to fork out for this endless list of school-sanctioned uniforms and assorted gym kits, which just about bankrupted them.

Family knitted what we couldn’t afford. As a result, I would be permanently posted to the outfield during cricket in case my jumper brought shame on the school. My mum said she’d never spent so much in one shop – not to make me feel guilty, you understand: we just didn’t do sprees in our house. My parents never said, ‘Do you know what this is costing?’ But I had a dawning awareness that they were making huge financial sacrifices, as well as some emotional ones I knew nothing about.

I’d find out later that my mum desperately didn’t want me to go. She said nothing at the time, though – she wanted to support me and kept her fears well hidden, but I suspect that they ran deeper than the normal mothering instincts. I believe she was concerned about the potential for abuse at the seminary. Years earlier, she hadn’t let me join the Cubs because apparently the then troop leader had instructed some boys that in order to get one badge, they had to run around the Scout hut in their undies!

Because I came from a family of practising Catholics, I think a lot of people thought my parents were living vicariously through me, that I was unwittingly fulfilling their dreams by going to the seminary. I know my dad was proud of me and what he thought might be my chosen path in life, but beyond that, other peoples’ criticisms couldn’t have been further from the truth.

The material necessities took a bit of sorting out, but otherwise at home – when I think back – there was almost a unilateral denial that the big day was coming. If anything, it was the parish as a whole that made me feel like I was torch-bearer for their collective ambitions in the build-up to my imminent departure. I remember a dinner lady at my junior school taking me to one side and looking at me with this odd expression of reverence. I thought for a moment she was going to burst into tears. Then she said to me, very earnestly, ‘What you’re doing is a wonderful thing. You know that, don’t you?’ All I can remember thinking is, ‘Well, this is awkward,’ because I didn’t understand what all the fuss was about.

At heart I remained pretty carefree – like most 10-year-old boys – as to me, the prospect of this new school I’d be going to was all just a bit of fun. But when an ordinarily stand-offish dinner lady hugs you like that, you can be forgiven for thinking she knows something you don’t. She made me feel more like a terminally sick kid being given one last treat: ‘Am I ill? Why have you bought me a baseball cap? Why do all the adults keep hugging me?’

When I visited the seminary for my entrance exams/orientation day, the place looked positively idyllic. Near Wigan as it was, it had lakes for canoeing and fishing, two tennis courts, even its own nine-hole golf course! Upholland resembled a posh Butlin’s, but with priests instead of Redcoats; in fact, I was a little disappointed not to see a mono-rail running around the grounds it felt so like going on holiday.

My older brother Mark had become very protective, and spoke his mind about his misgivings in my build-up to leaving. He was worried that I didn’t entirely know what I was getting myself into – and God, he was right. A month earlier, he’d taken me on to the back field by Hankey’s Well and said, ‘You know where you’re going, there’s no sex and no booze, don’t you? It ain’t fuckin’ worth it, if you ask me.’

I’d just shrugged. It was the first time this marvellous decision of mine had been directly challenged. ‘Well, if you are gonna do it, you’re gonna need a vice.’ He’d taken out one of his Benson & Hedges, sparked it up and passed it to me. Teenage boys don’t tend to be big on sharing, whether it’s their B&H or their feelings. Offering me my first full cig, as inappropriate as it might seem, was the nicotine hug he was incapable of giving me himself, and it felt like a monumental gesture at the time.