Читать книгу Dominion Built of Praise - Jonathan Decter - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

Poetic Gifts: Maussian Exchange and the Working of Medieval Jewish Culture

The propositions that are known to be true and require no proof for their truthfulness are of four kinds: perceptions, as when we know that this is black, this is white, this is sweet, and this is hot; … conventions, as when we know that uncovering nudity is ugly and that recompensing a benefactor with something of greater honor is beautiful.1

—Maimonides, The Treatise on Logic

The previous chapter discussed issues related to the performance of panegyrics, essentially the Sitz im Leben of the texts, while also making some broad observations about the nature of medieval Jewish culture in Islamic domains. This chapter will delve further into what function panegyrics actually held and why they were so pervasive across relations among poets and patrons, gaons and donors, and between friends. What was it about panegyric that was fitting to all these types of relationships? The answer, in part, can be found by analyzing panegyrics’ metapoetic and self-referential discourse, how authors described them and how readers received them.

The most common terms for describing panegyric writing in medieval Hebrew discourse, apparent in the shirah yetomah that closed the previous chapter, belong to the semantic range of “gifts,” most often in the mundane sense of gifts exchanged among humans and sometimes reaching over into the language of Temple sacrifice, offerings to God. The language of gift giving, and the constitution of panegyrics as gifts, permeates several levels of Jewish social organization in the Islamic Mediterranean, from the relations between geonic academies and satellite communities, to those among poets and patrons in a given locale, to those among intellectuals across and within Mediterranean centers. What these sets of relations among individuals, institutions, and communities shared was a foundation on bonds of loyalty—elements that tied people to one another in relationships that were essentially voluntary, or at least not inviolable.

Referring to the well-known study by Roy Mottahedeh, Loyalty and Leadership in Early Islamic Society, which demonstrates the essentiality of loyalty-based relationships (more than formal legal relationships) for the functioning of Islamic court life, Marina Rustow has investigated patronage and clienthood in various Jewish contexts, including ties between rabbinic leaders and followers and bonds among more humble folk. Rustow shows that “parallels between courtly literature and everyday letters demonstrate how deeply the modes and manners that we ascribe to courtly etiquette permeated other realms of relationships whose stability rested on the binding power of loyalty.”2 In particular, she considers the dynamic of granting benefaction (ni‘ma) and the gratitude (shukr) that such benefaction required, a dynamic that engendered the “continuity and coherence” of life, political and otherwise.

Jewish life in the Islamic Mediterranean may be said to have functioned according to what Marcel Mauss called (in French) a system of prestations and contre-prestations—usually rendered in English as a system of “total services” and “total counter-services”—in which the exchange of gifts provided an essential component of group coherence.3 Mauss’s classic book, The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies, demonstrates that, cross-culturally, the giving of a gift obligates the receiver to reciprocate not only in kind but rather with something of greater value than the original gift (a point also recognized by Rustow in her study). For Mauss, reciprocal relationships need not require exchange between equal parties; in fact, structural inequality is precisely what allows the cycle of benefaction to perpetuate. The ongoing and dynamic process of indebting and repayment is said to give societies their coherence and structure by tying individuals to one another within and beyond their kinship circles. Mauss’s short book has enjoyed a remarkable afterlife, especially in anthropology and sociology but also in history and literary studies, and many elements of this seminal work have been developed, nuanced, or challenged.

I will not attempt here to describe all of the types of loyalty-based exchanges that made up the “continuity and coherence” of Jewish life in the medieval Mediterranean.4 Rather, I wish to reflect upon the metapoetic trope by which medieval Jewish authors referred to their compositions, especially panegyrics, as “gifts,” and upon the use of gift discourse more broadly. The rhetoric of gift giving pervades panegyric letters and poems throughout the region and reveals a great deal about the functions that their authors and readers ascribed them. I will argue that portraying panegyrics as gifts constituted them as material objects whose value either served as or demanded reciprocation, thus initiating or maintaining bonds of loyalty. Toward the end of the chapter, I consider the specific implications of describing such gifts through the language of the sacrificial cult of ancient Israel, as though these gifts were offered not so much for their human recipients as for the divine.

Fortunately, I am preceded in the application of Maussian theory to the study of panegyric by a number of scholars of Greek, Latin, and Arabic poetry.5 For Arabic, Suzanne Pinckney Stetkevych discusses a panegyric by the pre-Islamic poet al-Nābighah intended to negotiate the poet’s reentry into the Lakhmid court. With the qaṣīda, the “poet/negotiator virtually entraps his addressee by engaging him in a ritual exchange that obligates him to respond to the poet’s proffered gift (of submission, allegiance, praise) with a counter-gift (in this case absolution and reinstatement), or else face opprobrium.”6 Beatrice Gruendler also draws Mauss (and Mottahedeh) into the exchange between patron and poet: “The poem is a token of the poet’s ongoing allegiance just as the patron’s gifts and benefits were tokens of his ongoing protection and benevolence. To this end, the poem performs a service and thereby repays the patron’s gifts and relieves the poet of some of his liability. The relationship emerges as a mutual exchange. However, it is not one of discrete transactions of giving and thanking; rather, it represents an ongoing process.”7

Before continuing, I wish to introduce two further concepts of gift exchange. First is the idea that gift exchange generally involves objects that are incommensurate and inter-convertible, at least one of which is more symbolic than material. Thus, I am not discussing the exchange of a stock for cash value or the trade of a quantity of flax for a quantity of silk but rather the exchange of praise for such things as elevation in rank, favors, luxury items, or even money itself. The disparate “goods” generally correspond to the social standings of the two men, each of whom has something to offer the other that he does not already possess. Because there is no exact “exchange rate” between goods, the relationship by which giver and receiver are bound does not dissolve once the transaction is complete but, as Gruendler suggests, remains dynamic. This leads to the second point, the distinction between what has been termed “disembedded” and “embedded” exchange. In the former, the exchange belongs to a sphere that has an independent and discrete economic reality (stock for cash) such that the transaction might be considered “complete”; the relationship dissolves once the transaction has been satisfied. In an embedded exchange, the transaction participates in and supports noneconomic institutions such as friendship, kinship, religious affiliation, and learned societies.8

This is not to say that money cannot be an element of embedded exchange. The matter is similar to what is sometimes said about marriage in our own day: it can involve money; it just can’t be about money. Hence panegyric, even panegyric composed for money, is bound by an ethical structure wherein a strict quid pro quo was considered uncouth, blameworthy, and a violation of an unwritten social code (this will be discussed further in Chapter 5). Embedded exchange was always hailed as an ideal; disembedded exchange was sometimes suspected of being the reality. Jocelyn Sharlet writes that in “medieval Arabic and Persian discourse on patronage, there is widespread concern that the exchange of poetry for pay may have more to do with material wealth and individual ambition than ethical evaluation and communal relationships.”9

Central to the issue is the nature of the institution of patronage (Ar., walā’; lit., “proximity”) in the Islamic world, which has been the subject of a significant amount of scholarship in recent years.10 Apart from the earliest usage of the term in the strict legal sense, referring to the arrangement by which non-Arabs could be grafted into the Muslim umma (nation), it had expanded by the tenth century to encompass a broad range of social relationships. The broad application of patronage is summarized nicely by Rustow, as:

using one’s influence, power, knowledge or financial means on behalf of someone else, with an eye toward benefiting both that person and oneself at the same time. Investments of this type could lead to the production of art, literature, architecture, science, philosophy, or works of public hydraulic engineering. Rulers and their courts used them to advance their claims as the bestowers of material and cultural benefits on their subjects, and thus to achieve legitimacy, and indeed, rulers were in a special position to accumulate (or better: extract) the material resources that allowed them to act as patrons. But others bestowed patronage too: village big-men, long-distance traders, elders of the community, or anyone with wealth or power to redistribute. Patronage also included the formation of narrowly or locally political alliances in which a person of higher rank protected or helped a protégé. To sound more sociological about it, patronage was any investment of resources (material or not) for the purposes of giving benefit and receiving some social benefit in return.11

Viewing the phenomenon of Jewish panegyric within this broad context allows us to link the vast range of bonds considered throughout this book and the use of writing, especially ornate writing, as a binding instrument.12 The term mawlā itself is terribly ambiguous in that it can refer either to the more powerful or the less powerful person in the patronage relationship, the patron or the client. Yet the fluidity of this term, and hence the broadness of the institution, is key for understanding the dual role of a figure such as Hai Gaon, who was at once patron (in that he bestowed intellectual resources and prestige upon satellite communities and leaders) and client (in that he relied upon their largesse and recognition to maintain the academy and his own position). The inclusion of material exchange was permissible within patronage relationships but was not their defining characteristic, either. Failure to recognize this point has led to some of the misperceptions about professional poets and “courtliness” referred to in Chapter 1.

If we consider exchanges of praise for favors, recognition, honor, and protection, we see the dynamics of exchange—and the rhetoric of gift exchange, in particular—pervasively among Jews throughout the Islamic Mediterranean. Similar dynamics are operative in the discourse of the academies and in mercantile relationships, in friendships, in family bonds, and among communal members of equal or disparate social station. Any of these relationships could include exchanges of money, but monetary exchange need not have been part of any single exchange. We will see that the receiving of “gifts,” one of which could be praise, essentially obligated the receiver to reciprocate in some way. Al-Andalus was no exception; although it is famed for the exchange of praise for objects of value, even here we need to conceive of a patronage system that encompassed, but was not limited to, remuneration through money, garments, wine, and the like; just as often, exchanges involved favors, honor, and praise itself.

Gifts in the Discourse of the Academies

The operation of the academies of Sura and Pumbedita, as well as the competing academy of Jerusalem, was dependent upon intellectual and monetary ties with communities throughout the Mediterranean. Satellite communities directed questions on legal and other topics to their gaon of choice, usually including a donation for the academy, and could expect a response in return. At the same time, the gaons had to pursue allegiances actively, especially since communities could turn to another academy if they chose. We therefore find geonim playing several roles simultaneously as respected leaders invested with authority but also as fund-raisers charged with maintaining relations with supporters.

Soon after he had assumed the office of gaon of Sura, Sa‘adia Gaon sent a letter to Fustat in his homeland, Egypt.13 The letter contained teaching about the nature of the Oral Law and promised that another letter containing “warnings and rebukes” (hazharot ve-tokhaḥot) would follow in order to lead the community toward the proper observance of God’s law. Sa‘adia also asks the recipients to “inform us every day of your well-being, for it is the welfare of our soul. Without an army, there is no king, and without students, there is no honor for sages.” Sa‘adia had an intuitive sense for the reciprocal and interdependent nature of even the most hierarchically structured power relationships.

In the second letter, which contains the promised “warnings and rebukes,” Sa‘adia begins by addressing the recipients with various honorific terms and offering greetings from ranks of the academy. In the present letter, Sa‘adia describes the first as an iggeret teshurah, a “gift epistle.” He probably meant that, whereas most epistles by gaons were sent in response to petitions from communities that contained contributions for the academy, this “gift epistle” was unsolicited and was sent gratis. The gaon thus used the “gift” to initiate a cycle of exchange and to promote bonds of loyalty. While calling the letter a “gift” may have suggested that no specific—or, at least, monetary—repayment was expected, Sa‘adia knew that he could essentially impose a debt; following Mauss, we might say that there was no such thing as a “free gift.”14

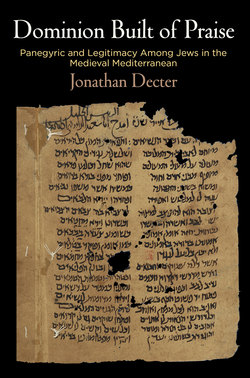

Gaons often refer to letters received from distant communities (especially those that were accompanied by contributions) as gifts.15 What gaons offered their supporters in return was praise itself, which could take on various forms. Most ritually oriented was the mentioning of names during the recitation of the qadish prayer on the Sabbath (a practice that seems to relate to pronouncing the caliph’s name during the Friday khuṭba). Natan ha-Bavli relates, in connection with the installation of the exilarch, that when the cantor recited the qadish, he included the exilarch’s name and then offered separate blessings for the exilarch once again, the heads of the academies, the various cities that sent contributions to the academies, and individual philanthropists.16 One version of a qadish containing praise for an exilarch and gaons has come down to us (ENA 4053; Figure 6) and reveals that the practice involved more than simply citing names but also appending magnifying expressions of blessing and praise.17

Figure 6. Qadish, including praise for an exilarch. ENA 4053.1r. Image provided by the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary.

Returning to the poem by Hai Gaon that opened Chapter 1, we see an obvious reciprocal exchange whereby the monetary gift was exchanged for praise; even if the composition of the panegyric may have been technically voluntary, it was in practice obligatory. Hai assures Yehudah that his monetary gift will gain him favor with God and that the money is being well spent. Yet, instead of offering simple gratitude, Hai composed for Yehudah the extensive and labor-intensive panegyric.18 The exchange between Yehudah and Hai was not (or, at least, not primarily) about the wedding of Yehudah’s son. The wedding served as a pretext for asserting the essential dynamics between the two men and the communities of Baghdad and Qairawan. Yehudah offered allegiance and financial support for the academy, and Hai offered Yehudah recognition and a panegyric that brought him fame among his contemporaries and, it would seem, for posterity. Without the panegyric, the cycle of exchange would have been incomplete, and the incommensurability of the “goods” ensured the cycle’s continuation. Finally, Hai not only improved the reputation of his addressee but also bolstered his own image by presenting himself as the authority of the Exile who possessed the authority to declare a holiday for his students.

Similarly, in a poem addressed to Avraham ha-Kohen ha-Rofe (first half of the eleventh century) that laments the death of the recipient’s father, the author opens: “My poem is set, metered, purified, and also ordered; in an eloquent tongue it is sent to the lord of my soul as a gift and offering (minḥah u-teshurah), to master Avraham ha-Kohen.”19 Although we cannot identify the author with certainty, it is likely that he was an associate of the Palestinian academy, perhaps even a gaon, since Jacob Mann identifies several other texts by prominent figures of this academy praising the recipient.20 The poem was not, of course, a gift for the deceased father but rather for the son, whose own honor was enhanced through the memorialization of his father’s merit and the brief praise included for the son.

Praising affiliates of the academy seems to have been one of the gaon’s many functions. In the following letter, Sherirah Gaon of Pumbedita addresses an aluf in Fustat (possibly Avraham Ben Sahlān) who had praised Shemariah Ben Elḥanan and seemingly sought confirmation from the gaon. Sherirah holds that the praise is justified, reviews Shemariah’s wisdom and rank within the academy, and adds a bit of hyperbole:

We have dwelled upon what you mentioned, aluf, may God preserve you, concerning praise of the magnificent, our esteemed, strong and steadfast Rav Shemariah, head of the Nehardeah row in our academy, may the Holy One give him strength, might, aid, and encourage him, son of Rav Elḥanan, may his memory be for a blessing, for he is the Head of the Order. For it is truly so and we more than anyone know his praiseworthy qualities; for who like him do we have from the East to the West? He is a lion in its pride, a great one of the academy. We know of the wonder of his wisdom and the inner chambers of his knowledge … and his strength in Torah beyond others. Were this not the case, we would not have appointed him to be the mashneh and we would not have made him head of the most honored of the three rows of the academy. To praise him is our first priority (shivḥo ‘adeinu rav min ha-kol).21

Praising affiliates was indeed a priority for the heads of the academies for at least two reasons: 1) in order to garner or reward loyalty among communal figures in satellite communities; and 2) to give communal figures something, an object of sorts, to signify their status as recognized by the gaon and before their communities. In the document above, we witness another dimension of the dynamic, which is the local aluf’s praise of Shemariah, which had to be corroborated by the gaon. Had the aluf praised someone whom the gaon did not deem worthy, it may have amounted to a kind of faux pas in the chain of command.

Not only individuals but also communities are told that they are praised far and wide (indeed, many “community panegyrics” have come down to us). In one letter by Shemuel Ben ‘Eli to the community of al-Kirkānī, we read: “We—whether we are near or far—are with you [pl.] in prayers and good blessings and we praise you and extol your ethical qualities (middot) among the communities. The elder among you we consider like a father, the young we consider like a brother and son, and all of you are most dear to us.”22

Offering and disseminating praise in exchange for loyalty was an expectation, and when the cycle of exchange was broken, it was noteworthy. In a Judeo-Arabic letter, Shemuel Ben ‘Eli writes concerning a community that had “abandoned the paths of our love” (hajaru subūl mawaddatina) by ceasing to send letters and charitable contributions (mabārrahum). Still, Ben ‘Eli writes, “we shall never cease invoking blessings unto God (al-du‘ā’) on their behalf and extending them blessings (muwāṣalatahum bi’l-berakhot) wherever we can. We even follow our courteous practice of spreading their praise (basṭ madḥihim) and commending them (batt shukrihim).”23 The fact that the head of the academy indicated that the praise would continue in the absence of the contribution demonstrates that praise was expected when a contribution was sent. Indeed, praise was a sufficient means of repayment, and Shemuel’s confirmation of ongoing praise may have been enough to persuade (read: “guilt”) the community to reestablish relations.

A letter sent on behalf of the “two congregations” (likely Rabbanite and Karaite) of Alexandria to Ephraim Ben Shemariah, head of the Palestinian academy in Fustat, opens with extensive literary praise for the academy and makes a transition to similarly elaborate praise of Ephraim. Dated 1029, the letter praises the gaon and the academy for assisting previously in a case of freeing captives and asks them to take up the cause again in a similar scenario. Yeshu‘a Kohen Ben Yosef, the author of the letter, describes praising the recipient as the very aim of writing: “The purpose of this letter of ours to your honor, our brother, the man of our redemption, is to complete your praise, to specify your laudation, and to offer glory for the beneficence of your deeds that you performed when you broadened your hearts, opened your hands, and acted with great generosity in order to free your captive brethren.” The author assures the reader that a letter that Ephraim had previously sent had been contemplated “by all of the community” and that the people “praised you for the vastness of your wisdom and the beauty of your rhyme.” Yeshu‘a also writes that his own letter should be read before the entire community of Fustat in order to exemplify proper behavior and to show them that they, too, are compelled to fulfill the commandment of freeing captives.24 Again, we see a type of exchange of incommensurate objects (praise for money) embedded within a broad social relationship preceded by the current correspondence and in which author and recipient were allied by institutional context and common cause, even bound by the same religious obligation. They were part of a discrete group whose conventions of address centered on the offering of praise as an embedded exchange.

Gifts of Praise Among Individuals in the East

We have seen above that praise, especially when laboriously executed, could be constituted as a gift of material and even enduring value. Broadly speaking, poetry was recognized as a type of material object among Jews throughout the Islamic Mediterranean. As Miriam Frenkel points out, poetry was one of the key pursuits of the Alexandrian Jewish elite, all of them merchants, who maintained contact with one another through letters. This group created cohesion through informal yet ritualized bonds of friendship that focused on the profession of covenant and the exchange of favors and goods; the exchange of poems essentially filled the same role as the exchange of other goods and services. In one letter composed in Arabic script, the cantor Avraham Ben Sahlān places poetry (qaṣīda wa-rahuṭ) on the same level as other ḥawā’ij, “necessities,” a term generally reserved for material goods. The author asks that the recipient send him a poem and includes a portion of a Hebrew poem with which “I praised Abū al-Faraj Hibba Ibn Naḥum,” a respected figure in the Alexandrian community.25 Poetic exchange was one factor among several that helped create the group’s boundaries and exclusivity.

One panegyric by El‘azar Ben Ya‘aqov ha-Bavli specifies that the author sent it following a “settling of accounts” (Ar., muḥāsaba) between poet and mamdūḥ. This does not suggest that the poet was paid for the poem but rather that the poet and his mamdūḥ were already bound in some sort of financial relationship. The precise sum of money owed (three dinar and four awqīn) is given in the superscription, and the poem playfully casts the repayment in sacralized terms, “He sanctified himself in all matters so much that he made his payment the weight of the sanctuary weight” (cf. Ex 30:13). With the panegyric, Ben El‘azar not only acknowledged receipt but also perpetuated the relationship.26

An early panegyric by the Eastern poet ‘Alwan Ben Avraham includes a fictionalized dialogue in which he asks passersby about his mamdūḥ. They respond: “Why do you ask about your chief when he is very distant?” The poet replies that his heart has become a laughingstock because of the mamdūḥ’s absence. The dialogue continues, and in the conclusion the poet turns to the mamdūḥ and implores him to fulfill his pledge and respond. Failure to reciprocate in correspondence was tantamount to breaking a pledge.27

A very different dynamic is witnessed in a poem by ‘Eli he-Ḥaver Ben ‘Amram, who requested compensation for poems in more than one instance. In this case, the poet grumbles to Yehudah Ben Menasheh, a bridegroom whom the poet already knew, that he failed to invite ‘Eli to his wedding. After praising Yehudah, ‘Eli concluded the poem: “Read this that is given unto you; I inscribed it in order to testify to your name … and send me a ‘freewill offering’ (nedavah; cf. Ex 35:29) with a generous heart.” Had the poet been invited to the wedding, one imagines, he may still have written a panegyric but not demanded compensation since the exchange of favors would have already been satisfied.28

In short, panegyric was used in the Islamic East as a mediating device within a host of relationships whose dynamics of exchange could be quite diverse. Most often, these involved institutional-communal connections or relations between individuals who already knew each other and were bound within a cycle of exchange.

In al-Andalus

The rhetoric of gift giving permeates the Andalusian panegyric corpus, apparent already in the shirah yetomah discussed in Chapter 1. Earlier than this, a fragmentary panegyric to Ḥasdai Ibn Shaprut by Dunash Ben Labrat recognizes the annual contributions that the mamdūḥ makes to the academies of the East and expresses gratitude for the material items that the poet received personally. Dunash uses the language of gifts throughout:

[Ḥasdai] acquired a good name and built a wall of kindness. Every year he sends an offering (minḥah) to the judges [in Babylonia] …

And to me he sent portions (manot), gave gifts (matanot), and filled vessels with thousands of measures,29

onyx and gold, sealed-up purses, perfect and beautiful garments and wrappings.30

This is the last line of the poem to have reached us, though we know it continued at this point. One would expect, as Shulamit Elizur suggests, that after expressing thanks for the bounty that Dunash received from his patron, the poet would have offered in exchange a dedication in the remaining lines. I would further assume that the conclusion made reference to the poem’s value and possibly described it as a gift (given in exchange for the gifts mentioned above). The ethical nature of the embedded exchange was not undermined by the fact that it included objects of value. The relationship was not predicated on a simple quid pro quo but rather on a deeper and more enduring bond whose cyclical nature would be expected to continue.31

The superscription to a panegyric by Yehudah Halevi to an anonymous recipient states that the poem was sent as “thanks (todah) to someone who had given him a gift.”32 Another addressed to Yosef Ibn Ṣadīq states that the mamdūḥ had sent Halevi “a gift of a poem and a gift” (teshurat shir u-matanah).33 Thus poems could accompany, be given in exchange for, or quite simply be gifts. More elaborately, another poem by Halevi for the same figure was composed upon Halevi’s departure from Córdoba; the poet adjures himself to glean all that he can from Ibn Ṣadīq’s wisdom, which is described as provisions for a journey. The poem is an offering (minḥah) in exchange:

Take delicacies from [Ibn Ṣadīq’s] mouth as a provision,

And his words, behold a cake baked on hot stones!34 Eat and go with the strength of the meal!

Gather for yourself manna today, for tomorrow you will seek it as one who seeks something lost.

In exchange give him (hashev lo) truth, a gift (minḥah) sent forth, pearls of poetry with every precious stone!

Perhaps it will delight him, and perhaps the gift of Yehudah (minḥat Yehudah) will be sweet.35

Here there is no monetary exchange, but there is an intellectual exchange that captures and reinforces the social bond between the two men. The place of panegyric in the mutuality of a relationship is sometimes stated expressly. After pleading with Abū al-Ḥasan Ibn Murīl to send him a letter, Halevi wrote: “Read my poem and forget not my covenant (briti).”36 Failing to recognize the covenant between the two men could lead to the dissolution of the relationship.

A panegyric written during Mosheh Ibn Ezra’s youth to a certain Abū al-Fatḥ Ben Azhar asks the mamdūḥ to intercede with another patron who had looked unfavorably upon the poet, requests a letter from the mamdūḥ, and offers him the poem, “Bind upon your throat a necklace made from the finest of our jacinth and beryl.”37 Here there is no request for money but rather for the performance of a favor.

The very first poem of Ibn Ezra’s collection of homonymic epigrams, Sefer ha-‘anaq (Book of the necklace), dedicated to Avraham Ibn al-Muhājir, refers to poetry as a gift and alludes to the name of the patron (father of many nations, i.e., Abraham; cf. Gn 17:4):

Listen to these [verses], O princes of poetry, singers of the age,

and raise up their preciousness as an offering and gift

to the father of many nations, a prince who holds power38 so much that he struggled with men and with God!39

In all likelihood, Ibn Ezra received financial support from the known courtier though the patron-poet relationship likely extended beyond the dedication of a single book in exchange for pay. We might presume that the intellectual bond preceded the commissioning of the work and that the dedication functioned within a system of embedded exchange.

Gift language also permeates Ibn Ezra’s poems sent to fellow intellectuals from the late stage of his life after he had left al-Andalus; one poem bears the superscription, “He wrote from Castile to the exalted Nasi, his brother, may God have mercy on him, before he met him.” In the poem, Ibn Ezra refers to the “covenant of love” between himself and the mamdūḥ (“should I forget it, may my right hand wither”; cf. Ps 137:5) and concludes with a dedicatory section whereby the poet consecrates the poem to the mamdūḥ as a gift, “Here is a gift of poetry.”40 This subject brings us to the next section of this chapter.

Dedicating Poems

Beatrice Gruendler calls attention to the dedicatory section of Arabic panegyric as a “speech act,” phrasing that combines “action and utterance,” whereby the words of dedication have the effect of constituting the poem as the recipient’s possession (even when delivered orally). Arabic panegyrics sometimes collapse the entire relationship between poet and patron, with the poem as a mediating device, into a single neat word, manaḥtukahā, “[Herewith] I dedicate it to you.” Gruendler stresses the reciprocal nature of the patron-poet relationship, how the “benefits and duties of the patron mesh with the benefits and rights of the poet,” engendered most poignantly in the dedication, “which ties a firm and far-reaching bond between the two.”41

As Dan Pagis notes, Mosheh Ibn Ezra used dedications with great frequency both in poems and in letters, most often using phrases such as “take this poem” or “behold this poem.”42 In a poem appended to a letter for Shelomoh Ibn Ghiyat, itself a response to a poem, Yehudah Halevi includes a dedication that fills eight lines.43 Prior to this, Shemuel ha-Nagid used dedications in the few panegyrics that he composed for others.44 In one, the Nagid praises his mamdūḥ, “I love you, beloved of my soul, as I love my own soul” and stresses the mamdūḥ’s wisdom, knowledge in Talmud, and alacrity in religious observance before concluding: “Take from me words chosen from bdellium, rhymes on a scroll.”45 There is no reason to think that the Nagid was paid for these verses, especially given the intimacy of the language suggesting near social parity.

Again, dedicatory language appears in poems that participated in patronage relationships that included the bestowing of material objects. A poem by Ibn Gabirol begins with a dedication, “Take this poem and its hidden stores, its precision and poetic themes…. Lord of my soul, may his heart and ears be attentive to understand my eloquence, also my poem and its supplications.” The poet thus gives the mamdūḥ the poem and hopes that his pleas will be heard in return. We do not know exactly what these requests entailed; they might have been for something tangible, such as money or a garment, or possibly something more abstract, but the exchange was portrayed as belonging to the world of embedded, rather than disembedded, exchange.46

Dedications seem to have been introduced into Hebrew panegyric in al-Andalus and to have spread from there to authors in the Islamic East. An anonymous panegyric sent to the Yemeni merchant and community leader Maḍmūn II refers both to the gifts given by the mamdūḥ to the community and to the poet’s gift to the mamdūḥ. The poet praises the “nagid of the nation of God” for his valor and kindness and includes, “He succored the whole nation and supported its falling, young and old alike. His generosity is like the rain; those who seek his gifts are glad.” In the lengthy dedication, the poet identifies himself as a Levite (i.e., a singer) and writes, “Hear this, nagid of the wise men of Torah,47 lord of the rulers and glory of the gaons, take this gift that is here presented; I sent it to remove anguish.”48 The poet’s gift was not presented in the hope of specific remuneration but was inscribed within a reciprocal bond between leader and community.

We close this part of the chapter with a translation and discussion of a fascinating epistolographic poem (TS 13 J 19.21; Figure 7) mentioned and transcribed by Goitein and later published by Yehudah Ratzhaby.49 It was sent by the student (talmid) Yiṣḥaq Ibn Nissim Parsi to his peer Abū Zikri Yiḥye Ibn Mevorakh. The author had received a letter from the latter that contained verses based on a famous poem by Ibn Gabirol (“I am the poet and the poem is my slave!”).50 Parsi now responds with a letter of his own, opening with the Jewish version of the basmallah (be-shem ha-raḥman, “in the name of the Merciful”) and two biblical verses, all typical of letter introductions. He then inscribes a poem in the same meter and rhyme as Ibn Gabirol’s and undoubtedly of the poem he had received from Ibn Mevorakh. The metered poem begins in line four:

1. In the name of the Merciful,

2. The meek shall inherit the earth and shall delight (Ps 37:7).

3. Great peace unto them who love your Torah (Ps 119:165).

4. To you, O prince, beloved and friend of my soul! Peace unto you, my people’s lord and confidant

5. whom mountains have raised up as a gift (teshurah)! I have sent you [this poem] to be a mantle.

6. If you please, let it be your mantle veil, wrap yourself and turn to its foundation

7. so that princes will consult you as an oracle (Jb 12:8) and poets will praise you for its splendor.

8. Verily, poetry is your eternal slave but the poems of others you enslave for your use!

9. May my poem be a friend of pure heart to you. Your heart hurt me by leaving;

10. it was connected to my heart all your days like a chain bound to a neck.

11. I delighted in your letter’s arrival; in your kindness you gave me a choice gift.51

12. The poem came and I was in awe of its treasure, and on Shelomoh Ibn Gabirol it was based!

13. I was astounded by your words, my friend, “Write a letter and send it along!”

14. How can I write while my heart is with you? Woe, on the day you left it was taken captive.

15. By departing you seized my innards and so my heart mourns.

16. Behold I cry and do not know if it is for my heart or for you!

17. My heart’s pain has grown with your separation and there is none to help.

18. [I am] tormented and have not found anyone pure of heart, intellect, or wisdom.

19. May God plant you in his garden as a pure seedling and reveal to us his beloved (the Messiah)!

20. May you delight in the knowledge of God and His splendor and enjoy the wisdom of His creation’s52 secret!

21. Then the poem will speak happiness for you, my prince, beloved and friend of my soul.

Following the poem, the letter continues with standard blessings, compliments for the recipient’s writing, and requests for further correspondence; as Goitein points out, the verso contains related content written in Judeo-Arabic.53 The letter is fascinating on a number of levels. First, it attests to the widespread fame of Ibn Gabirol’s poetry and the phenomenon of imitation (mu‘āraḍa, contrafaction), even among students of a young age. Second, it was not composed by a known or professional poet but represents the attempt of an “amateur”; the poem exhibits numerous literary merits (opening and closing with the same phrase, clever plays on biblical verses) but also has its shortcomings (misuse of gender in pronouns and frequent deviations in meter). Third, it demonstrates the clear epistolographic purpose of the poem and is a response to another poem that itself made up part of a letter. Finally, the author refers to his friend as a “gift” (teshurah) offered by the mighty mountains (4). What gift can one offer a “gift”? The answer, of course, is a poem, a panegyric, described here as a “mantle.” The friend’s letter is likewise described as a gift (9); this reference is proximate to the author’s dedication “May my poem be a friend of pure heart to you” (7); that is, the friend is a gift and the poem, the poet’s gift, is a friend. The epistolographic poem thus draws extensively upon the metapoetic discourse of gift exchange, a discourse expressing—indeed, constituting—the mutual bond of the correspondents.

Figure 7. Letter with panegyric by the talmid Yiṣḥaq Ibn Nissim Parsi for Abu Zikri Yiḥye Ibn Mevorakh. TS 13 J 19.21r. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

In short, Jewish culture in the Islamic Mediterranean functioned according to a shared discourse of gift exchange across a range of social relationships—among poetic correspondents, poets receiving material remuneration and their beneficiaries, heads of academies and their communal adherents, among merchants and students. Of course, these relationships were hardly uniform. Some involved financial aspects while others exhibit nonmaterial exchanges of different sorts, but all were premised on reciprocal bonds that were expected to be cyclical and enduring. Although praise was not the only aspect of these relationships, it constituted a “good” of great value, especially insofar as it could extend the mamdūḥ’s reputation before his peers.

The Rhetoric of Sacrifice

For the most part, the “gifts” referred to in the discussion above have been devoid of valences of sacrificial offering. In this concluding section, I consider the phenomenon of sacrificial language in the rhetoric of exchange relationships.54 The central question is whether the introduction of God as a third party and the dynamics of atonement substantially alter the picture we have depicted about the mutuality of human exchange relationships, particularly in light of the Maussian framework.55

In the letter that opened Chapter 1, Hai Gaon describes the contribution from Rav Yehudah Rosh ha-Seder as a “gift [that] will be considered by God an offering and sacrifice (minḥah ve-azkarah). He made it ransom for him for pardoning and atonement.” Play on the language of the sacrificial cult can also be far more extensive, as in the following letter by Shemuel Ben ‘Eli, which deals primarily with the appointment of Zekhariah Ben Barkhael to the rank of av bet din.56 Here the head of the Baghdad academy addresses the community to which Ben Barkhael was being dispatched: “That which arrived to us and him [Ben Barkhael] from you will be considered for you, our brethren, like a whole offering, like incense seasoned with salt, like a burnt offering, like a grain offering…. And when this letter arrives to you, read it in public with a sweet tongue … and a joyous voice.”57 “That which arrived” was, in all likelihood, a monetary contribution. What the community received in exchange, in addition to the presence of the sanctioned av bet din, was the letter itself, which was to be read aloud and intoned with beauty, thereby bringing glory upon the community and reinforcing its tie to the academy.

Did Ben ‘Eli or the recipients of the letter really believe that the monetary donation had expiatory power for the givers? Does using sacrificial language rather than the language of human gift exchange truly alter the way in which the donation was considered? That is, did Ben ‘Eli and the community both recognize that the donations were simply keeping the lights on (or the lamps lit, as it were) and read the language of sacrifice with ironic distance? Was the rhetoric a kind of inside joke among intellectuals, the kind of literary play for which the medieval Hebrew poets are famed (the language of sacrifice is, for example, exploited to describe the garden or the body of the beloved)?58 Or should we view this as a kind of cultural practice that created or reinforced some core value of medieval Jewish society? The answers to these questions are, of course, difficult to glean from the sources, but I will try to evaluate the function of this discursive phenomenon.

There is little doubt that the representation of monetary contributions as sacrifices is on some level rhetorical, but this does not mean that the rhetoric is necessarily empty. It conveys to the reader that giving money to the academy is a type of divine service, and it is arguable that the sacrificial metaphor may have been important for claims of the academy’s legitimacy. At the very least, the rhetoric allows the recipient of the letter to imagine something more complex than a two-party human exchange relationship but instead a three-party dynamic, whereby the academy head acts as a kind of mediator between the donor and God. Rather than participating in mutual back-scratching, both donor and recipient can act as though they are working together in a single cause, likely deepening the sense of embedded exchange. Thus we might ask whether the use of sacrificial language throws a proverbial wrench into the application of the Maussian framework in the study of medieval Jewish exchange practices.

Following a paradigm proposed for Late Antique Jewish culture by Seth Schwartz, Marina Rustow reflects upon medieval Jewish culture under Islam between the poles of “reciprocity” and “solidarity.”59 According to Schwartz’s definitions, a reciprocity-based conception holds that “societies are bound together by densely overlapping networks of relationships of personal dependency constituted and sustained by reciprocal exchange.” On the other hand, a solidarity-based model means that “societies are bound together not by personal relationships but by corporate solidarity based on shared ideals (piety, wisdom) or myths (for example, about common descent).”60 In Schwartz’s view, whereas Greco-Roman society was grounded in institutionalized reciprocal structures, biblical religion and rabbinic Judaism theoretically and largely eschewed such structures in favor of a solidarity-based system and, in this sense, did not constitute a “Mediterranean society.” Adding a deeper dimension to Goitein’s use of the phrase and noting the shift from the rabbinic to medieval periods, Rustow cleverly concludes that “the Jews of the tenth through twelfth centuries as reflected in the documents of the Cairo Geniza, then, unlike Schwartz’s ancient Jews, were a ‘Mediterranean’ society.”61

Geonic culture was clearly dependent upon reciprocal relationships, evidenced so richly by the exchanges of praise, loyalty, and material items detailed above. This culture of reciprocity was seen as fundamentally ethical in that the exchanges were of the “embedded” variety. Yet even this was sometimes not enough. Rather than portraying a gift to the academy as a mere contribution to a scholarship fund that brought its donor honor, it could be said to affect and delight the divine and to engender efficacious atonement. The rhetoric of sacrifice, whereby all donations are said to belong ultimately to God, intimates a system of solidarity.

Returning to the letters by Hai Gaon and Shemuel Ben ‘Eli, do we have here a system of reciprocity merely masquerading as a system of solidarity? Should we doubt the gaons’ sincerity? It would be cynical and exaggerated to view the leaders with the severity with which Martin Luther impugned the papacy for selling indulgences in order to raise funds for the erection of Saint Peter’s Basilica. The trajectories of reciprocity were portrayed, and quite possibly perceived, through a lens of solidarity. At least rhetorically, the language of ideological solidarity remained paramount.

Mauss, for his part, was hardly oblivious to reciprocal relationships that involved third parties such that exchange occurred between a donor and something otherworldly with the human recipient serving as a facilitator or intermediary. The Gift was preceded by some time with a work that Mauss had written (at the age of twenty-six) in collaboration with his fellow Durkheimian (also twenty-six, and a philo-Semite) Henri Hubert: Sacrifice: Its Nature and Function.62 In classic Durkheimian fashion, the book characterizes sacrifice in social terms such that the phenomenon of sacrifice—far from being a self-abnegating act of total surrender—belonged to a system of reciprocity. Mauss later integrated this element within The Gift, where he titled the last part of the introduction, “Note: the present made to humans, and the present made to the gods,” which itself includes a further “note on alms.” Here, he argued that “destruction by sacrifice” is an “act of giving that is necessarily reciprocated.”63 Mauss sees here the beginnings of a theory of “contract sacrifice” wherein the “gods who give and return gifts are there to give a considerable thing in the place of a small one,” a system characteristic within monotheistic religions as well. Rather than seeing a structural opposition between giving to the human and the nonhuman, Mauss focuses on giving to men who are manifestations of the nonhuman such that the realm of the nonhuman penetrates the realm of the human, “The exchange of presents between men, the ‘namesakes’—the homonyms of the spirits, incite the spirits of the dead, the gods, things, animals, and nature to be ‘generous toward them.’”64

Mauss was not dealing with the rhetoric of sacrifice so much as actual sacrifice, and it would be difficult to call the academies’ leaders “manifestations” or “homonyms” of God rather than “mediators” or “representatives.” The language of sacrifice simply deepened the claim of solidarity-based exchange. In any case, as Schwartz and Rustow stress, solidarity and reciprocity are not strict alternatives; they are paradigms, both opposing and complementary, through which we might meditate upon specific cultural practices, including rhetorical ones. In the case of exchanging donations to the academy for praise, reciprocity was plain to all; solidarity existed because it existed rhetorically.

The language of sacrifice is also apparent within correspondence that is relatively private or noninstitutional. TS 8 J 39.10, an unpublished epistolary formulary, preserves a copy of a letter addressed to “our lord and master Yeshayahu son of […]ḥyah” that opens with extensive blessings. After acknowledging receipt of a gift “sent amid love and affection,” the author goes on to express embarrassment for having needed the donation and adds “we asked the Creator of all to make it like the whole sacrifice upon the altar and like the regular meal offering in the morning and in the evening.”65 The author probably belonged the group that Mark Cohen has termed the “conjunctural poor,” people of means who had fallen upon hard times. The financial assistance was given through a private, rather than an institutional, channel and was the cause of some “shame” for the recipient.66 The rhetoric of the letter created the veneer—or, quite possibly, the true perception—of social solidarity involved with the donation.

Not all usage of sacrificial language was tied to monetary donation. An unpublished letter, TS 10 J 9.4v, contains a poem whose main purpose was to wish good health upon an addressee who had fallen ill. The anonymous poet, who laments that he could not offer a real “gift” (teshurah), calls his composition a type of sacrifice pleasing unto God:

May the Lord of praises prepare healing balm and all types of remedies … and strengthen the respected, beneficent leader, the choice of His people, a turban upon all of the communities. To bring you a gift (teshurah) is not in my power, though I was determined and constituted it as prayer (samtiha tefilot) pleasing before the face of God as an offering (qorban); may it be considered like a sacrifice (zevaḥ) and burnt offering (‘olot). It heals like spell-inducing water!67 We sing a song like the song over the splitting of the depths (i.e., the Song of the Sea, Exodus 15), and the daughters of my people go out with timbrels and drums and sing amid dance.68

The poet offered the “sacrifice” that will hopefully incite God to heal the sick recipient.69 The letter certainly draws upon the grandeur of Israel’s past and likens the delivery of the infirm addressee with the delivery of Israel from bondage. Solidarity is placed at the center of the relationship by stressing a shared historical and theological consciousness. What else the anonymous author wanted in return is unclear. I would presume that author and addressee were already involved in an unequal relationship involving the addressee’s support of the poet and that the letter was intended to maintain that relationship.

Similar is the dynamic of a short letter, written in a beautiful hand, addressed to a certain Ḥiyya, “Pride of the God-Fearing.” The letter requested wine, which had been prescribed by the author’s doctor after bloodletting and had previously been promised to the author. The letter concludes with blessings of well-being in Hebrew rhymed prose and adds “may his offering (minḥah) bring prosperity quickly like a fragrant sacrifice (qorban), and peace.”70

Is the function of sacrificial rhetoric different in private and institutional correspondence? Earlier in this chapter, I cited examples that I described as “playful,” such as El‘azar Ben Ya‘aqov ha-Bavli’s referring to a sum of money received as “the weight of the sanctuary weight”71 or ‘Eli he-Ḥaver Ben ‘Amram’s request from a mamdūḥ for a “freewill offering.” How do we know when reference to a gift as a sacrifice is playful and when it is serious? The answer is that we cannot always know this with certainty, and our judgments are necessarily subjective. What is striking is how continuous the rhetoric of sacrifice was across the social and political strata of Jews in the Islamic Mediterranean. Both in the context of the geonic world and in Andalusian circles, the rhetoric of sacrifice played a role in group formation and cohesion, of building political and communal ties between center and periphery, on the one hand, and of boundary marking for a social elite, on the other. While I would assign greater import to the rhetoric of sacrifice in institutional contexts, it arguably presented some dimension of solidarity in personal contexts as well.