Читать книгу Dominion Built of Praise - Jonathan Decter - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Performance Matters: Between Public Acclamation and Epistolary Exchange

And my speech I purified, smelted, and cleansed

on balanced scales, marked it out with a stylus….

I worked on it from afternoon to evening. It is sweet like honey….

Recite it every Sabbath like the readings from the Torah and the Prophets,

write and recall it throughout the generations.

—Hai Gaon

These are verses from the conclusion of a lengthy panegyric (more than two hundred lines, all in quantitative meter and monorhyme) by Hai Ben Sherirah (d. 1038), gaon of the Sura academy in Baghdad, in honor of Rav Yehudah Rosh ha-Seder, a dignitary in Qairawan. After the wedding of Yehudah’s son Dunash, Yehudah sent a letter to Hai, along with a monetary gift for the academy. In the panegyric, Hai expresses gratitude for the gift and offers extensive praise for Yehudah, Yehudah’s wife,1 Dunash, and the bride’s family. A small portion of the praise for Yehudah is as follows: “Through him nations in Togarmah and Qedar are blessed. His kindness is upon all like rising vapor and incense. All his oils are scented like spiced early rain, aloe, myrrh, and cinnamon, every powder burning (Sg 3:6). His beneficence is great, too vast to measure. Who can seek out his praise and who can count it when he gives without asking, disperses for others to keep. A thousand gold pieces are like a gerah in his eyes. Before him a hundred thousand kikarim are like an agorah. To every patron he is a king upon a throne and seat; before him others are like concubines.”2

In the poem, Hai also refers to the arrival of Yehudah’s letter and gift: “It arrived like lightning reaching Venus, shining and gleaming. I kissed it and fastened it on me like a sash. I set it in my place exposed, not concealed, and showed it to every guest to rejoice with me and sing. My portion from his wedding that was sent as a gift (ashkarah) will be considered by God an offering and sacrifice (minḥah ve-azkarah). He made it ransom for him for pardoning and atonement. Out of [the gift], I made a holiday [for scholars] and a special day of rejoicing for all the sages of my academy, for lifting spirits and exchanging gifts (terumiyah ve-liteshurah).”3

We begin this section on the social function of Jewish panegyric with this poem because it captures several aspects of the complex dynamics that we will be discussing in this and the following chapter. It is clear that this panegyric was presupposed by and participated in a broad social and administrative system that involved trans-Mediterranean communal bonds, correspondence, the sending of monetary donations, and hyperbolic address. Yehudah held the title Rosh ha-Seder (“head of the order”), which would have been bestowed upon him by a Baghdadi gaon—likely, in this case, because of philanthropic and scholarly activity.4 The concluding dedication conveys that Hai composed the poem from noon until night and commands that others learn and recite it on the Sabbath and new moons to be remembered for generations. Following the poem, the letter continues with praise and assures the recipient that “our companions, students, and loved ones” will “learn and teach [the poem] and publicize it far and wide.” Those who hear it will “not find all this praise strange or foreign” but rather “a word aptly spoken” (cf. Prv 25:11).5

Here we witness the sending of a poem from a gaon, a man of the highest spiritual and intellectual rank, to a prominent donor and communal leader who was nonetheless the gaon’s social subordinate in a far-off community. Despite his higher status, the gaon took the posture of a poet praising his mamdūḥ, appropriate because the donor was arguably a kind of “patron.” The panegyric was part of an epistolary exchange whereby the poem, despite its ornate style, functioned essentially as a letter, one whose value was enhanced by its meter, rhyme, and beauty, and the labor of whose execution was emphasized by the poet-gaon.

This exchange between gaon and communal leader, between the Islamic East and the Islamic West, falls roughly in the middle of the period under discussion in most of this book, c. 950–1250. The poem extends backward in time to a Hebrew panegyric tradition that had been developing for a century and certainly would not be the last such panegyric to be composed. The formal features, including quantitative meter and monorhyme, indicate that Hai was following the Arabized prosodic innovations introduced by Dunash Ben Labrat in al-Andalus during the tenth century (one of Dunash’s panegyrics to Ḥasdai Ibn Shaprut likewise emphasizes its being composed in quantitative meter).6 Finally, the poem illuminates the central subject of the present chapter concerning the performance practices of Jewish panegyric. On the one hand, the poem is clearly part of an epistolary exchange. On the other, Hai’s text testifies to the broader circulation of both the initial letter and the poetic response beyond the eyes of their immediate recipients. The gaon set Yehudah’s letter out for “guests” and ordered that the panegyric be read publicly.7

One set of questions that we must address in determining what Jewish panegyrics were ultimately for—what function they held in the constitution of medieval Jewish society—is how they were received, performed, and circulated. Were they delivered orally, before small or large audiences? Read privately by their addressees? What relationship exists between the written testimonies and oral/aural experiences? We will see that the performance practices of Jewish panegyric in the medieval Islamic Mediterranean were variegated and had written as well as oral dimensions, though the sources elucidate most poignantly the degree to which panegyrics were embedded within epistolary exchange. This is not entirely surprising, since written texts testify to the practices of written culture primarily but to oral culture only serendipitously; it might be the case that the occasional hints that we have of oral recitation are the tip of an iceberg that is largely submerged or has melted away. Still, we do learn that figures were acclaimed aloud, sometimes publicly and even ceremonially, as suggested by Hai’s poem. The written text of the panegyric, which was sent over a distance in response to a letter, preceded the oral performance, but we may assume that public acclamation also took place.

* * *

The primary purpose of this chapter is to consider the evidence for oral and written aspects of Jewish panegyric practice in the contexts of the Islamic Mediterranean, including the world of the academies, local political structures, mercantile circles, and other social and intellectual relationships. Although much of the information considered is rather technical—including scribal inscriptions, the layout of manuscript pages, lists of books—the chapter remains focused on broader cultural issues such as the nature of patronage, the place of panegyric in society, the machinery of disseminating images of leadership, and the continuity and disjunction of Jewish regions across the Mediterranean. The chapter also offers close readings of texts with a focus on political vocabulary.

The discussion begins by reviewing the practice of Jewish panegyric in the Islamic East, where the tradition began, and then turns to the practice in the Islamic West, particularly within al-Andalus. I review the relatively scant evidence that we have for the oral performance of Jewish panegyric, whether in public ceremonies—what might be called “political rituals”—or in small gatherings, and the more extensive evidence we possess regarding its place in epistolary exchange. The chapter stresses the epistolary context for Jewish panegyric alongside a performative, sometimes ceremonial, one while also breaking down the dichotomy presumed to exist between the two. I do not propose an austere culture of poetic reading that negated aural experience; as demonstrated, poems that played a primarily epistolary function could be recited publicly subsequent to reception.

In discussing the subject of Jewish regionalism within the Mediterranean, I also offer, inter alia, a critique of what has generally been dubbed the “courtly” Jewish culture of al-Andalus. It has often been asserted that the Jews of al-Andalus imitated the performance practices of Islamic courts where poets lauded caliphs for pay and thus engaged in a kind of miniature Jewish court culture; a key element of this portrayal has been the image of the Jewish patron surrounded by professional poets who recited his praise in exchange for money. Although the courtly image is justified to an extent, it has also been partly misunderstood, a point that has had the effect of distorting our ideas about Andalusian Jewish panegyric and its function. In the Islamic West, as in the Islamic East, Hebrew panegyric practice involved epistolary as well as performative elements, which makes its role more continuous than has been imagined. Further, the performative settings of Jewish panegyric recall both the hierarchic majlis as well as the more egalitarian mujālasa, as distinguished in the Arabic context by Samer Ali and discussed in the Introduction to this book.8

Evidence for the Oral Performance of Panegyric in the Islamic East

Our sources for the oral performance of Jewish panegyric in the Islamic East are fairly sparse.9 Even more rarely do we find indications of oral performance in connection with an actual political ceremony. Natan ha-Bavli, writing in the tenth century, reports that when a new exilarch was invested on the Sabbath, he stood under a canopy beneath which a cantor also placed his head in order to “bless [the exilarch] with prepared blessings (berakhot metuqanot), prepared the previous day or the day before, in a soft voice so that no one could hear them save those sitting around the dais and the young men beneath it. When he blessed him the young men would respond ‘Amen!’ in a loud voice but all the people remained silent until he had finished his blessings.”10

Because Natan’s text was originally written in Judeo-Arabic and this section survives only in a medieval Hebrew translation, we are left to deduce what Arabic word lay behind the Hebrew berakhot (blessings). It seems likely that the word was du‘ā, “invocations with blessings,” which were frequently used when acclaiming men of power in Islamic political ceremonies.11 On the one hand, the acclamations associated with this installation call to mind the setting of a majlis ‘ām, a public assembly, and the installation of a caliph. On the other, the fact that the hearing of blessings was limited to a small circle of elites distinguishes the performative context.12

The only mention in Natan’s account of “praises” comes after the conclusion of the Musaf service, when the exilarch returned to his home amid an entourage of congregants, “and when the exilarch exits all the people go out before him and after him and say before him words of poetry and praise (omrim lefanav divrei shirot ve-tishbaḥot) until he arrives at his home.” One wonders exactly what these divrei shirot ve-tishbaḥot entailed. Were they sung or recited? Were they in Arabic or in Hebrew? Were they specific for the occasion, previously composed, or spontaneous? There may be some parallel here also to the public entourage in Muslim celebrations. As Paula Sanders notes, “popular” festivals in Fatimid Cairo could move from the “streets, to al-Azhar, to the palace” and could involve poets offering “invocations and blessings.”13 As I have argued elsewhere, the ceremony described by Natan “drew simultaneously on the idioms of ancient Jewish rites and contemporary Muslim ceremonial to articulate an image of leadership and political legitimacy that blended Jewish categories … with resonances of caliphal power.” There I also concluded that “the elites of Babylonian Jewry recognized that presiding over the Jewish world was a type of statecraft and, as Clifford Geertz notes, that ‘statecraft is a thespian art.’”14

An important text that is highly suggestive of a ceremonial performance is a long panegyric in honor of Daniel Ben ‘Azariah (d. 1062), a gaon of the Jerusalem academy who emanated from a family that claimed descent from King David. This gaon was able to bolster the position of the Palestinian academy even unto Iraq and was greatly esteemed by the Palestinian community of Fustat. He seems to have had some difficulty securing loyalty among Jews in the Islamic West, though he was praised in verse by none other than Shemuel ha-Nagid of al-Andalus as a kind of political endorsement.15

In 1057, around the time that Ben ‘Azariah assumed the position of gaon, the poet ‘Eli ha-Kohen composed a panegyric in his honor using a form, structure, and style that were entirely unique.16 It is clear that the poet saw his poem as related to the Arabic poetic tradition, since he gives it the heading qaṣīda (Ar., “formal ode”) in the manuscript. Although the poem suggests no clear liturgical context, its form is closer to the style of the classical piyyut than the relatively new Arabized poetry of the Andalusian school, despite the fact that this latter form had penetrated Jewish communities throughout the Islamic world by the eleventh century and would have been familiar to Ben ‘Azariah. Like the ‘avodah liturgy of Yom Kippur, the poem begins by recounting the creation of the world, leading to a long yet selective review of Israel’s history that culminates with praise for Ben ‘Azariah.17 Much of the historical summary dwells on tracing Ben ‘Azariah’s lineage from King David, which, as Arnold Franklin notes, “dramatically suggests that [Ben ‘Azariah’s] assumption of the post of gaon be viewed as part of a divine plan extending back to creation itself.”18

The copy of the poem that survives is an autograph draft that includes alternate versions of verses throughout. Although we have no external testimony that this panegyric was performed, I agree with Ezra Fleischer, who published the poem, that the internal evidence suggests a public performance, quite possibly from the time of the gaon’s investiture (alternatively, the poem could simply have been given to the gaon or recited in a small audience). In the section reviewing the history of Israel, the text focuses on the moment of King David’s investiture (lines 135–45), in all likelihood alluding to the performative context of the poem.

The poem gives no indication of the setting in which it was recited, but the manuscript does bear a date, the thirteenth of Nissan, just before the festival of Passover. The association with Passover is further corroborated by allusions within the poem itself. Just after recounting the Israelites’ enslavement in Egypt, the plagues, and the Exodus, the poet dedicates several lines to the laws of Passover, concluding with Ex 13:10, “You shall keep this ordinance at its set time from year to year” (lines 86–91). Did a ceremony of installation take place on Passover? As discussed in the Introduction, the dedication of Arabic panegyrics often coincided with particular Islamic festivals and hence the recitation of the panegyric for Ben ‘Azariah at Passover might present a Jewish analogue to this practice. Although Fleischer found the link with Passover puzzling, there is a certain logic in associating the festival with a political ceremony. The Exodus from Egypt marks Israel’s entry into the realm of the political, becoming in the desert a hierarchically organized camp, a kind of community, polity, or even quasi-state. Even if the poem were not written for an investiture specifically, Passover would have been an appropriate occasion for reiterating—indeed, representing—the divine origins of the Jewish “polity” and solidifying bonds of political loyalty. This poem cannot be categorized neatly as “secular” or “sacred”; it demonstrates just how intimately the two were linked such that the elevation of a man’s status was integrated within sacred history and the act of praising him was imbued with sacrality.

Although we have no other description of a Jewish ceremony as elaborate as that of the exilarch’s investiture as described by Natan ha-Bavli, occasional texts from subsequent centuries refer to political rituals that recount many of the same basic elements. Shemuel Ben ‘Eli was a rosh yeshivah (head of the academy) in Baghdad who penned a number of epistles to Jewish communities in Iraq, Persia, and Syria between 1184 and 1207.19 Several of the letters concern a certain Zekhariah Ben Barkhael, a native of Aleppo who wrote to Ben ‘Eli in his youth, studied with him in Baghdad, and ultimately became the sage’s successor. In 1190, Ben Barkhael was appointed av bet din (head of court) and dispatched to communities in Iraq and Syria. His responsibilities included the rendering of judgments, gathering funds, and the appointment of “scribes, cantors, prayer leaders, and community heads.” Throughout the letters, Ben Barkhael is presented as an extension of and proxy for the rosh yeshivah himself, a “limb of the body,” as Ben ‘Eli calls him in one instance.20 Jews should pay homage to the av bet din much as they would to the rosh yeshivah himself; yet Ben ‘Eli is also careful to safeguard his own rank by describing Ben Barkhael’s status as derivative and a matter of investiture.

The epistles’ aim was to establish the new av bet din’s, and hence the rosh yeshivah’s, authority and legitimacy in satellite communities. To this end, they recount at length Ben Barkhael’s praiseworthy qualities and request that certain rituals be observed concerning his public appearances, including his verbal “magnification” (Heb., giddul). The epistles thus refer to ceremonies of power that have already taken place, convey the appointee’s praiseworthy qualities through writing, and call for further rituals to be observed in the future. In one of the Hebrew letters, after enumerating Ben Barkhael’s merits, Ben ‘Eli writes:

When we saw these precious and honored characteristics in him, including fear of God, love of the commandments, and intelligence and knowledge, we laid hands upon him (samakhnuhu) as av bet din of the yeshivah and gave him authority to judge, teach, and permit firstborn animals (for slaughter) (cf. b. Sanhedrin 5a), to explicate the Torah in public, to set the pericopes, and to appoint the translator. Before he expounds, “Hear what he holds!”21 should be said and after he expounds his name should be mentioned in the qadish…. It is incumbent upon the communities, may they be blessed, when they hear that he is approaching, that they go out to greet him and come before him with cordiality so that he may enter a multitude (‘am rav) with glory. When he comes to the synagogue, they must call before him and he must sit in glory on a splendid seat and comely couches with a cushion behind him, as is appropriate for av bet dins. He also possesses a signet ring to sign documents, rulings, and epistles that are appropriate for him to sign.22

The “laying of hands” is a gesture of investiture from one of higher authority to one of lower authority (based on Moses’ investiture of Joshua in Dt 34:9), while the signet ring is a standard emblem of political authority throughout Near Eastern cultures.23 Many of the points in this letter are reiterated in a second epistle, now in Judeo-Arabic with Hebrew phrases interspersed. The rosh yeshivah writes that “his presence among you is in place of our presence” and continues (Hebrew in italics): “We conferred distinction upon him, selected him and made it incumbent to treat him with honor and respect. We elevated his station and gave him the title (talqībuna) av bet din of the yeshivah.24 It is incumbent upon the communities of our brethren, may they be blessed, that, when they hear of his arrival and his appearance before them, they gather to meet him with rejoicing and gladness, exuberance, joy, respect, magnification (i‘ẓām), abundant offering, and reverence and that his seat be made beautiful.”

This text also goes on to mention rituals associated with Ben Barkhael’s teaching, pronouncing his name in the qadish, the signet ring, and his right to make appointments. Ben ‘Eli concludes, lending authority to the appointee while claiming his own jurisdiction: “His speech is our speech and his command is our command. He who brings him near brings us near and he who distances him distances us.”25

“Magnification” and “reverence” undoubtedly involved praise of some sort, though it is difficult to know whether this included the formal presentation of panegyric. Ben ‘Eli certainly saw the enumeration of the judge’s virtues a requisite purpose of his letter and recognized that the verbal pronouncement of Ben Barkhael’s greatness was essential to constituting his aura of authority and ultimately his effective leadership. Ben ‘Eli recognized that dominion was built of praise.

Epistolary Panegyric in the East

In comparison with our knowledge of the oral performance of Jewish panegyric in the Islamic East, our knowledge of the place of panegyric in epistolary exchange is quite extensive. As suggested above and exemplified by the poem that opened this chapter, many panegyric texts functioned essentially as letters or as part of a correspondence in which a poem accompanied a letter proper, itself often written in rhymed prose with extensive literary effects. Hai Gaon’s poem to Rav Yehudah was intended for a dual purpose: to function as a letter (in response to another letter) while allowing—indeed, mandating—broader circulation and oral performance.

Over the course of the century prior to Hai’s correspondence with Rav Yehudah, Jewish letter writing had undergone a revolution, owed to Jewish knowledge of Arabic epistolary practices and the expanded functions of correspondence in the organization of the Jewish world. Letters were written for any number of reasons: to update a loved one on one’s state, to inform a business partner on dealings, to initiate a relationship with someone of higher or lower rank, to ask for or offer a legal opinion, to request money or favors of a recipient, or to offer gratitude for a previous kindness. Most of these epistolary registers would be expected to include praise for their addressees, which could be as simple as a few well-chosen terms of address or as extensive as a rhymed, metered poem spanning hundreds of verses.26

Modern readers have sometimes been struck, even puzzled, by the amount of panegyric contained within Jewish letter writing. In fact, some letters seem to be little more than a long series of praises, especially striking since paper was sufficiently precious that letter writers covered every speck of available space, including the margins, with ink. Jacob Mann refers to one Geniza document (TS Loan 203.2), a letter by Sherirah Gaon of Pumbedita to Ya‘aqov b. Nissim of Qairawan, as “the end of a letter consisting merely of verbiage.”27 Yet these documents provide us with an intimate glimpse into the inner logic of medieval Jewish culture, for their rhetoric bespeaks some of its most fundamental conceptions of leadership, friendship, and interpersonal connection.

There has not yet been a comprehensive treatment of Jewish letter writing based on Geniza materials and in light of Arabic epistolary practices that takes into account the full range of stylistic differences across period, location, and social rank, though there have been various localized treatments.28 Goitein, of course, discussed (especially merchant) Jewish letter writing at many points in A Mediterranean Society, and Assaf, already in the early twentieth century, pointed out that epistles of the Baghdad academy from the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries followed a standard form that included long sections of praises and blessings at the beginning and end.29 Structural and rhetorical analyses of all types of Jewish letter writing preserved in the Geniza remains an important topic for research, but here I wish only to emphasize praise as a pervasive aspect; it is exchanged among people of all ranks and, especially in the case of more powerful figures, played a constitutive role in the establishment of political legitimacy. In the section below, I present a general overview of Jewish letter writing in the Islamic Mediterranean, including the nodes at which praise was integrated, and argue further for narrowing the presumed gap between written and oral elements of panegyric performance.

On the Art of Medieval Jewish Letter Writing

Jewish letter writing can be dated prior to the geonic period; there are several references to the sending of letters in the Hebrew Bible (e.g., Est 3:13, 8:10), and Jewish letters survive from Late Antiquity (obvious examples include the Bar Kokhba letters and the Pauline epistles, though there are others). Jewish letters by nasis are attested in Late Antiquity through references in the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds as well as in a comment by Eusebius. As Isaiah Gafni points out, within rabbinic literature, excerpts of epistles are quoted in Hebrew even within Aramaic contexts, which may speak to Hebrew’s status in formal correspondence either as a “national” or “trans-national” language. As Gafni also points out, it seems that Jews were well acquainted with the epistolary practices of Late Antiquity, illustrated colorfully by an anecdote in which a scribe in the service of Yehudah ha-Nasi drafted a letter to Caesar that the Nasi tore up and revised to make the opening salutation adhere to a more formal standard, “To the lord the king from Yehudah, your servant.”30

The transformation of the geopolitical landscape brought by the expansion of Islam dramatically changed the organization of the Jewish world. The central administrative preoccupation of the academies at Baghdad and the competing Palestinian academy was the cultivation and preservation of loyalty from satellite communities from the far west to the far east of the Islamic world. Gaons sought to create standards of practice over these vast territories, encouraged adherence to their legal authority, and solicited funds from distant communities to run the academies. The movement of the Babylonian academies to the capital of Baghdad in the late ninth or early tenth century situated the gaons at the center of power, an ideal position for executing their administrative tasks and for cultivating their intellectual tastes.31 New levels of connection between center and periphery were facilitated by the relative political unity, however fractious, of the ‘Abbasid Empire and the advent of rapid communication.

In many respects, the powers and responsibilities of the Jewish academies mirrored what was taking place administratively within the Islamic political world, whose governments also sought loyalty over vast territories and relied on an efficient system of mail delivery to bind center and periphery.32 Neither private Jewish nor Muslim citizens had access to this governmental postal system, but the academies were able to use their own emissaries to circulate its letters, likely following similar routes. Other Jewish postal traffic seems to have been maintained through the “serendipitous, although heavy, traffic of Jewish travelers” and a more formalized system that Goitein described as a “commercial mail service” wherein Muslim couriers delivered letters sent among Jews.33

Islamic civilization also witnessed the rise of the court scribe (kātib), a powerful office that required knowledge of rhetoric, religion, poetry, philosophy, and diplomacy.34 Letter writing became an art form in its own right that merited the composition of manuals offering advice for scribes including al-Risāla ilā al-kuttāb (Epistle to the secretaries), by ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Kātib; Adab al-kātib (The etiquette of the secretary), by Ibn Qutaiba; Adab al-kuttāb (The etiquette of the secretaries), by al-Ṣūlī; Tashīl al-sabīl ilā ta‘allum al-tarsīl (Easing the path to learning the art of letter writing), by al-Ḥumaydī; and the late fourteenth-century–early fifteenth-century Ṣubḥ al-a‘ashā’ fī ṣinā‘at alinshā’ (Morning light for the night-blind in composing letters), by al-Qalqashandī.35 As stated by A. Arazi: “Even an administrative letter should be composed according to artistic and literary criteria; in society’s view, it belonged to the domain of the fine arts, and accordingly, the kātib was considered above all an artist.”36 Members of the dīwān al-inshā’, the correspondence bureau or chancery, were expected to gain mastery over literary techniques associated with the composition of poetry; al-Khwārazmī, in reviewing the technical vocabulary utilized within the chancery, defines various types of wordplay and rhetorical devices using works of poetics as his basis.37

Epistolographic manuals not only reflect the aesthetic and intellectual ideals of the age but also reveal a great deal about how society was organized and how the relations among various ranks of people were imagined. Al-Ḥumaydī (c. 1028–95), who was born in Córdoba and died in Baghdad, intended his book for “private letter writing” (ikhwāniyya) and planned another book that would deal with “letters from rulers dealing with matters of governance” (sulṭāniyya).38 Within the volume on private letters, opening blessings are organized hierarchically according to the ranks and professions of the correspondents (caliphs, governors, scribes, judges, merchants). Although these openings essentially offer the same blessings for long life, for God’s kindness and favor, and so on, the precise phrasing encodes social rank and negotiates the status differential between writer and recipient. Some elements also relate to the particular profession, as when a merchant is wished good fortune and even profit in business.39 The Ṣubḥ al-a‘ashā’ similarly organizes blessings according to social rank, what is appropriate for a superior to send to an inferior (ra’īs and mar’ūs) and vice versa. One of the most unadorned forms of address occurs when a father writes to his son. When a letter is sent from a subordinate to a superior, the formulas tend to expand and become more elaborate rhetorically—for example, “May God elongate the life of the qāḍī (judge) in might (‘izz) and happiness; may He extend his prestige (karāma) and execute His kindness (ni‘ma) for him with the broadest well-being (‘āfiya) and the utmost security (salāma).”40 Actual letters discovered in Quseir, which were directed to an elder merchant, follow similar formulas.41 In short, blessings constitute a form of praise because their wording can mark the relative status of author and addressee.

The Geniza document Oxford e.74 1a–6b is part of a Judeo-Arabic transcription of an Arabic epistolary manual attributed to Aḥmad Ibn Sa‘d al-Iṣfahānī; the work was divided into twenty-one chapters, beginning with taḥmīdāt (doxology) and sulṭaniyāt, and included examples for different genres, occasions, and purposes, including the expression of condolence, gratitude, apology, and, of course, praise (al-thanā’).42 While the section on praise does not survive, it seems likely that it included formulations for figures of different rank. The existence of the text in Hebrew characters, which even preserves specifically Islamic formulations (including qur’ānic verses), indicates that the genre was sufficiently important among Jews to be studied and, in all likelihood, imitated.43 Further, a book list from the Geniza includes a work titled adab al-kātib, possibly the guide for scribes by Ibn Qutaiba.44

As Haggai Ben Shammai points out, the Judeo-Arabic correspondence of the academies adopts conventions of Islamic chancery correspondence.45 With likely precedent from Late Antiquity, numerous Jewish letters from the Islamic milieu open with an introductory formula of blessing, often in three parts, with dimensions of literary play. Examples of mellifluous letter introductions abound in Geniza correspondence. As is the case with the formulas for blessing in Islamic correspondence, the degree of ornament and even length usually correspond with rank. Sa‘adia Gaon gives examples of the types of wordplay that “we constantly write in our epistles” (fī rasā’ ilinā),46 and, in a fragment from an actual letter by Sa‘adia, itself a response to a panegyric, the opening blessings follow the same pattern.47 Here Sa‘adia was writing to a student of one of his disciples and likely invested the blessing with literary effect to demonstrate his skill, to “thank” the inquirer for his query and poem, and to mark them both as members of the same Jewish social and intellectual elite.

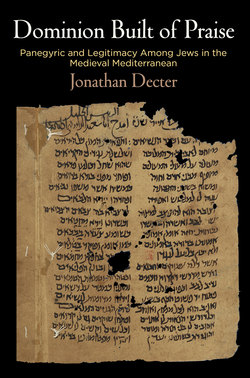

Although there are no manuals for Hebrew letter writing on the scale of the Arabic guides for scribes, there do survive Geniza manuscripts that compile Hebrew literary introductions for letters to addressees, both real and hypothetical, of various ranks (gaon, scribe, cantor, even synagogue caretaker), thus following the structural organization of Arabic epistolary manuals.48 The most significant of these formularies (TS J 3.3; Figure 3) was published by Tova Beeri.49 Such texts were probably intended to circulate as models for Jewish letter writers, including aspiring scribes. The mere existence of these documents demonstrates that Hebrew letter writing was also considered an art that adhered to conventions. Many of these introductions, and many actual letters dedicated to known recipients, include panegyric sections ranging from a few lines to several manuscript pages. Much of the literary creativity associated with versified panegyrics is observed within epistles, and the execution of literary praise was not dependent upon a “courtly” structure, per se; it was a by-product, or better a means, of human interconnection, whether bureaucratic, intellectual, mercantile, or familial.

There is also ample evidence for the Arabization of Jewish writing in letters exchanged between merchants or family members. Mark Cohen has demonstrated that authors of Hebrew letters found in the Geniza employ loan translations of Arabic locutions; examples include Jewish versions of the basmallah, certain epithets for God, opening and closing formulas, blessings for the addressee, and wishes that the addressee’s enemies be thwarted.50 In some cases, certain Hebrew words absorb the semantic force of their Arabic equivalents or cognates (shelomot = salāma; ne‘imot = ni‘ma; haṣlaḥa = tawfīq). Like Arabic letters, Hebrew counterparts sometimes incorporate Hebrew poetry or rhymed prose within the body of the letter.51 Hebrew held a certain cachet and was used even when both correspondents knew Arabic (as mentioned, this was also the case when Aramaic was the lingua franca of the Near East). The historical Jewish language was important in delineating boundaries for a specific community of learned Jewish men. Still, the spirit of their writing remained that of the Arabic milieu in which they lived.52

Figure 3. Epistolary formulary. TS J 3.3 (2r). Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Titulature

Another hallmark of letters of Arabic-speaking Jews from the Islamic Mediterranean is the addressing of a recipient, whether of higher or lower rank, with a series of appropriate terms and epithets that can be in Hebrew and/or Judeo-Arabic. This can be as simple as the ubiquitous “Our master and teacher” (mareinu ve-rabeinu) or as complicated as several lines of carefully chosen and rhetorically sophisticated phrases. In certain circumstances, the epithets selected represent actual titles that were bestowed upon their bearers in an official sense. In other cases, the epithets evoke the style of formal titles but are actually devoid of official function. It is not always easy to distinguish the official from the unofficial, but in either case, the formulations are telling measures of Jewish notions of power and “statecraft” and bear the stamp of Islamic titulature practices.53

Addressing a powerful figure in the medieval Islamic world was a highly ritualized act that adhered to fairly strict conventions. This was the case whether the “encounter” was in person or in writing.54 Caliphs, wazīrs, governors, scribes, and judges all expected to be addressed with strings of titles that marked their elevated status. As Islamic civilization developed an increasingly formalized political structure, the laqab (lit., “nickname”) was transformed from being a rather nonspecific form of admiration to an official, fixed, and prestigious honorific. Caliphs claimed laqabs for themselves as regnal titles and reserved the right to bestow them upon their favorites. Caliphs and other high-ranking officials often signed documents with nothing but their honorary titles, insignia known as ‘alāmas specific to the individuals.

Most cynically, Muslim historians quipped that titles were bestowed upon underlings with liberality because the caliphate had nothing real to offer them (such as money, a practice that has been followed well by university administrators). Yet such honorifics were an essential part of the political machinery of Eastern Islamic lands and also enjoyed more limited usage in the Islamic West.55 The terms selected convey ideals of the state, and the trained eye can glean a tremendous amount from such titles and epithets of address. The types of titles selected changed from one Islamic dynasty to another and were likely formulated in reaction to one another. The tenth century, it has been observed, witnessed the proliferation of compound honorifics, including as their second terms words like dīn, “faith”; and dawla or mulk, “secular power,” or less commonly, compounded with umma, “nation” and milla, “religious community.”56 Kramers argues that titles stressing worldly political affiliation, popular among the Shi‘ite Fatimids, were rejected by later Sunni dynasties in favor of titles stressing religious advocacy and fidelity.57

Titles of caliphs and other officials from Fatimid and Ayyubid Egypt are preserved in the handful of petitions addressed to powerful men by those of lower rank (including the truly lowly) found in the Cairo Geniza and the archive of Saint Catherine’s monastery in the Sinai desert.58 S. M. Stern published three petitions addressed to Fatimid caliphs or viziers, all of whom seemed to expect a high degree of honorary “verbiage” when addressed. Marina Rustow and Geoffrey Khan are doing more work in this area presently. The formulas of titles in these documents do not merely list flattering praises but reflect fundamental conceptions of the state. The Fatimid caliph is referred to repeatedly with phrases such as “Justice of the prophetic dynasty” (‘adl aldawla al-nabawiyya); the wazīr Ṭalā’i is “the Most Excellent Lord, the Pious King,59 Helper of Imams, Averter of Misfortune, Commander of the Armies, Sword of Islam, Succor of Mankind, Protector of the Qadis and the Muslims, Guide of the petitioners among the Believers.”60 And so forth.

Jews followed standard titulature practices when referring to Muslim leaders in Fatimid Egypt.61 A Jewish petitioner addressed Caliph al-Āmir (1101–30) “our Lord and Master, the Imām al-Āmir bi-Aḥkām Allah, Commander of the Faithful” and “the pure and noble prophetic Presence” (al-maqām al-nabawī al-ṭāhir al-sharīf).62 Similarly, TS NS 110.26r (Figure 4), published by Goitein, is composed in a mixture of Hebrew, Arabic, and Judeo-Arabic (Hebrew in plain font, Judeo-Arabic in italics, Arabic script in bold italics): “leader of the sons of Qedar, our lord and master the Imām … the great king, the Imām al-Āmir bi-Aḥkām Allah, Commander of the Faithful.”63 During the second half of the twelfth century, the author of a letter offers extensive blessings for the “Place” (i.e., the ruler),64 modified with a set of adjectives in Judeo-Arabic: “the holy, descended from ‘Alī, the Imāmī, belonging to the family of the Prophet, the pure.”65 This formulation, with its focus on pure descent through Muḥammad and ‘Alī, is specific to Shi‘ite leadership and reflects Jews’ full awareness of Fatimid court practices; Jews did not hesitate to refer to the rulers’ descent from the “Prophet,” thereby glossing over the Jews’ complicated relationship with recognizing the legitimacy of Muḥammad’s prophetic claim.66

Addresses to Jewish dignitaries, whether sent from lower rank to higher or vice versa, also include lengthy lists of honorifics, a practice undoubtedly derived from the use of laqabs within Islamic society.67 In some cases, Jewish leaders signed documents with ‘alāmas, which claimed status in the same manner as Muslim leaders.68 Further, the recipient of a letter could expect to be addressed with a string of terms specific to his rank, mode of leadership (spiritual/mundane), and relationship to the author.

In many cases, honorifics served as official titles.69 Gaons bestowed titles upon subordinate representatives of the yeshivah when appointing them. As mentioned above, when Shemuel Ben ‘Eli appointed Zekhariah Ben Barkhael to the office of av bet din, he used the root lqb to describe the process of bestowing a title: “Our elevating his station (tarfī‘ manzilatihi) and our giving him the title (talqībuna) av bet din of the yeshivah.”70 In a panegyric, Sahlān Ben Avraham (d. 1050) was praised for the very fact that he held “seven titles” (kinuyyin).71 In TS 8 J 16.18r, a certain Ovadiah is addressed as the “lofty lord (al-sayyid alajall), confidant of the state (amīn al-dawla), security of kingship (thiqqat almulk).” TS NS 246.22 is an early twelfth-century list, possibly a convenient reference for a scribe, of forty-three men along with their Hebrew titles. Each entry follows the same structure: “The sobriquets (alqāb) of So-and-So.”72

Figure 4. Petition for al-Amir bi-Aḥkām Allah (Hebrew, Arabic, Judeo-Arabic). TS NS 110.26r. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Bestowers of titles stress that they did not dole them out lightly or haphazardly, and titles seem to have been fairly specific to their holders; when Avraham ha-Kohen, who already possessed two Hebrew titles, was given a third, hod hazeqenim (glory of the elders), he was told that the name had been given “many years before to the [now deceased] elder Abū ‘Alī Ben Faḍlān at Baghdad” and “from then until now no one has been named this.” The author, whom Mann suggests was Daniel Ben ‘Azariah, specified his hope that the title would “elevate [Avraham’s] honor, magnify his name, and extend his authority.”73

State-oriented titles abound among addressees in the thirteenth-century dīwān of El‘azar Ben Ya‘aqov ha-Bavli. Here we encounter shams al-dawla (sun of the state), sharf al-dawla (nobility of the state), ‘izz al-dawla (might of the state), najm al-dawla (star of the state), and amīn al-dawla (confidant of the state).74 In some cases, titles are hinted at within Hebrew panegyrics for these figures, as when amīn al-dawla Ben Manṣūr Ben al-Mashā’irī is called pe’er misrah ve-ne’eman ha-melukhah (wonder of dominion and confidant of sovereignty). Occasionally, Arabic laqabs are simply inserted into Hebrew poems.75 The letters of Shemuel Ben ‘Eli also provide a wealth of information on titles and epithets, especially as they were bestowed upon lower ranks by the author. Terms such as amīn al-dawla, amīn al-mulk, thiqqat al-mulk, al-thiqqa, al-amīn, all of which signify that the figure is a trusted proxy of “sovereignty” or the “state,” are widely attested.76 It is particularly interesting that Ben ‘Eli continued to use the style of titulature characteristic of Shi‘ite dynasties after, as Kramers suggests, such titles had been denounced by Sunni critics as emphasizing worldly over religious aspects of Islam.77

In Ben ‘Eli’s collection, the same individuals are sometimes described within a single letter both in Hebrew and in Judeo-Arabic, which allows for a useful comparison of political discourse in the two languages. In some cases, the Hebrew titles are much more elaborate and richer in literary references pertaining to Jewish dimensions of legitimacy. Two brothers described in Judeo-Arabic rather generically as “the two exalted elders” (al-shaikhaini al-jalīlaini) are described in Hebrew as “two precious elders, the praised brothers, the pure, the natives who are like bdellium and raised beds of spices [Sg 5:13], honest men [Gn 42:11], the priests, sons of the steadfast.”78 The Hebrew, in addition to being more ornate, draws on their lineage, both to their immediate progenitors and to their descent from a long line of priests.

On the other hand, the Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic sometimes mirror each other such that the Hebrew renders phrases whose origin is clearly Arabic. A certain Mevorakh is introduced in Judeo-Arabic as the “lofty minister, proxy of the nation, trusted one of sovereignty, beauty of the ministers”; in Hebrew, he is described as “our minister and noble one, the minister, the leader, the respected, our lord and master Mevorakh, minister of the nation, trusted one of sovereignty, splendor of the ministers, crown of the Levites, treasure of the yeshivah.” Again, the Hebrew adds specifically Jewish dimensions and introduces a first-person plural voice (“our lord and master”). But most of the Hebrew formulations are translations of Arabic epithets (amīn al-mulk = ne’eman ha-malkhut; jamāl al-ru’asā = hod ha-sarim).79 Thus, much innovation occurred within the Hebrew language to accommodate the feel of Arabic praise writing and to capture a new mode of political discourse.

An extraordinary amount of literary care went into the selection of terms of address, whether in Hebrew or in Judeo-Arabic. A fascinating example is ENA NS 18.30, a twelfth-century Geniza fragment that preserves three drafts of a single letter composed by Ḥalfon Ben Natanel for Maṣliaḥ Ben Shelomoh ha-Kohen, head of the Jerusalem academy, which at the time was in Fustat. The letter was written to initiate contact between the scholar-merchant, who already enjoyed significant fame, and the gaon, whom Ben Natanel hoped would maintain contact and promote his reputation. The existence of multiple drafts in Judeo-Arabic for the same purpose clearly attests to the deliberateness that Ben Natanel invested in getting the tone just right. Comparing the versions is revealing:

1. My lord, my master, the most high, my support, my refuge, the most revered, my help, my stay, the most excellent, crown of the Exile, lamp of the religious community, perfection of exaltedness, fit for the domains of religion and the material world, his virtue and beneficence are widespread.

2. My lord, the most high, my master, the unique, the most excellent, the most beautiful crown, and the most perfect splendor, banner of banners, the source of perfection, the beauty of thought, ornament of the age.

3. My lord, my master, august as is proper for him, the sublime, foremost in priority, his exalted and sublime Presence.

From the first version to the third, the terms of praise actually become fewer in number. On the other hand, the author moved away from one-word descriptions (the most high, my support, my refuge), which are fairly generic, to more complex constructions, though these are not absent even in the first example. Already in the first example, the author has drawn upon terms of praise common within Islamic political discourse and Arabic panegyric, most importantly “fit for the domains of Religion and the World” (al-dīn wa’l-dunyā), a theme that had a long life span in Jewish discourse. In the second and third examples, the author has dropped terms referring to the Jewish community specifically (the Exile, the religious community) and offered a more universal depiction. Most importantly, the text moves toward vocabulary that is much more rare, abstract, and particular to royalty (“banner,” “Presence”).

Official letters were sometimes enacted dramatically through the oral presentation of their contents. A long letter sent on behalf of the congregations of Alexandria by Yeshu‘a Kohen Ben Yosef to Ephraim Ben Shemariah, head of the Jerusalem congregation in Fustat, requests contributions for the freeing of captives; even in such an urgent matter, the author did not fail to include six lines of complicated rhymed prose in the introduction (praise in honor of the community) and thirty in the body of the letter. In thanking Ben Shemariah for a previous letter, the author writes, “the whole community (of Alexandria) enjoyed your letter …, the greatness of your wisdom and the beauty of your rhymes.” Ben Yosef also requests that his letter be read to the community in Fustat.80 Shemuel Ben ‘Eli specifies that a letter should be read “in public and sweetly” (meteq lashon) and a joint letter from Sherirah and Hai Gaon to the Palestinian academy commands that the letter be read in public, “which was done there for our forefathers many times.”81 A letter of Maimonides to Yosef Ibn ‘Aqnīn describes a highly ritualized public reading of a letter from an exilarch such that the community members rose while the reader stood with the elders of the community to his right and left.82 The fact that epistles were frequently performed orally helps close the functional gap between epistles and oral panegyrics. And because epistles contained so much praise, their wide distribution demonstrates how public images of legitimacy could be disseminated and consumed.

Poetic Epistles, Epistolary Poems

As noted, many letters were written with a great deal of literary flair and made use of the same poetic techniques characteristic of “literature” proper. Similarly, many poems can be shown to have held an epistolary function. To be sure, letters and poems were distinguished in the medieval period and were theorized, respectively, in works on epistolography and poetics. At the same time, however, the Geniza preserves two book lists in which a dīwān al-mukātabāt (collection of correspondence) appears adjacent to a dīwān alshi‘r (collection of poetry), which points to differentiation but also to the proximity of the two forms.83 Further, no neat dichotomy can be maintained between texts that were “poems” and those that were “epistles.” At the very least, both utilized praise as a dominant mode of address, which points to their common rhetorical goals. The shared function of praise is corroborated by similar organizational strategies in works of epistolography and poetics, in that both tend to be structured around hierarchy. We have already seen that al-Ḥumaydī and al-Qalqashandī organize blessings of address according to rank; similarly, the panegyric section of Kitāb al-‘umda, a major work on Arabic poetics by Ibn Rashīq, is organized according to rank by specifying what qualities should be praised for occupants of different offices.84

One of our earliest Hebrew panegyrics, fragmentary though it is, is written in honor of Sa‘adia Gaon. It consists of strings of words, between two and five words each, that maintain a common end rhyme from between four and ten strings. After praising the mamdūḥ, the author asks a particular question pertaining to a matter of exegesis and expresses hope for a response. Do we have here a poem or a piece of correspondence? The answer is both. The verso contains the beginning of the gaon’s response, replete with the kind of wordplay that Sa‘adia describes in his commentary on the Book of Creation (Sefer yeṣirah) as belonging to letter openings, thus reinforcing the reading of the poem as a letter.85

The same is also the case with the lengthy panegyric that opened this chapter; it is certainly a poem but also meets standard epistolary expectations (greetings, congratulations, thanks, updates, closings), not to mention that it was written in response to a letter proper. Another poetic panegyric by Hai Gaon is introduced in the manuscript with a revealing superscription, undoubtedly inserted by a scribe of the academy, “the correspondence (Ar., mukātaba) of our master Hai Gaon with master Avraham Ben ‘Aṭa, Nagid of Qairawan.”86 In an important article on the Andalusian native Menaḥem Ben Saruq, Ezra Fleischer stressed epistolary dimensions of Menaḥem’s poetry and argued for the continuity, based on formalistic grounds, between the poet’s writing and Eastern precedents. I am wholly in agreement with this aspect of Fleischer’s article, which helps us situate Andalusian Jewish culture within the broader context of the Islamic Mediterranean.87

In the following section, I take the argument for the link in Jewish literary culture between the Islamic East and the Islamic West a step further by arguing for the basic continuity of panegyric performance as a hybrid oral-epistolary system. Although there are obvious structural differences between, for example, a gaon’s thanking a donor and a poet’s initiation of a relationship with a potential benefactor, the hybrid performance practice points to some level of shared function and interpersonal dynamic. This fact presses us to rethink the nature of Jewish culture in the Islamic West, particularly in al-Andalus, with respect to what has been termed its “courtly” quality. The section on the performance of Jewish panegyric in the Islamic West begins with a historiographic excursus on what I will call the “courtly hypothesis,” which, I argue, has had a distorting effect on our perception of panegyric’s function.

Jewish Panegyric Performance in the Islamic West

Andalusian Jewish culture has often been imagined as a kind of novum that broke forth ex nihilo, owed to the high degree of Arabization of Andalusian Jewry. If there is one word that is usually used to distinguish Andalusian Jewish culture from other Jewish cultures in the Islamic Mediterranean, it is “courtly,” though scholars are seldom precise about what this term means. Seventy years have passed since Joseph Weiss delivered his paper “Tarbuṭ ḥaṣranit ve-shirah ḥaṣranit” (Courtly culture and courtly poetry) at the first World Congress of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem (1947).88 By that time, research on the “court Jew” had gained momentum among researchers of different periods of Jewish history. Selma Stern had written her Der Hofjude im Zeitalter des Absolutismus (1640–1740), in which she presented court Jews as “the forerunners of the emancipation,” although debates raged over whether these Jews, who maintained contacts with and proved useful instruments of royalty, represented a people apart from their coreligionists or safeguarded their welfare (see, especially, the square critique of Stern by none other than Hannah Arendt).89 Likely influenced by the tragedy of the Holocaust, Yitzhak Baer had portrayed the court Jews of Christian Iberia with a mixture of admiration and suspicion.90

Weiss aimed to elevate the study of Andalusian Hebrew poetry from philological-textual research and biographical description to create a “history of the spirit.” His paper argued that the Hebrew poetry of al-Andalus reflected a Jewish “courtly” reality by drawing attention to the social manners idealized in the poetry as well as the lavish material surroundings described. Weiss wrote that “the Jews of the Arab courts who were close to royalty became the dedicated initiators of an independent Jewish court culture as a secular culture that was separate from Jewish society.” He suggested that “Jews’ experience in the Arab courts caused Jews to create their own similar culture and that the patron, in whose honor poets offered praise, stood at the center of this parallel culture.” At the same time, Weiss opined, “courtly Jewish society could not be anything, of course, other than a spiritual semblance [of Muslim courtly society] (albeit one abounding in brightness and splendor), but was deprived of all real political power.” Panegyric was marshaled as evidence in constructing this “court culture,” and the presumed structure of the Jewish court, in turn, has determined how panegyric has been conceived and interpreted.

Weiss’s paper became a classic in the field and remains cited widely, but its thesis has rarely been revisited.91 Questions we might ask include: Where exactly was this Jewish court? Was the patron as central as Weiss had imagined? To what extent can we generalize about Jewish patronage structures across periods (Umayyad, Taifa, Almoravid)? Weiss’s study had an impact on Schirmann, who, as discussed in the Introduction, saw the panegyric phenomenon as the paramount (and somewhat ugly) aspect of poetry as a “vocation.” Weiss also had a deep impact on Eliahu Ashtor, who assented to the courtly image and saw the poet-patron relationship as key to understanding the great explosion of Jewish intellectual production during the “Golden Age” of al-Andalus. His influential The Jews of Moslem Spain portrays a performance scenario wherein Yiṣḥaq Ibn Khalfūn recites a Hebrew poem aloud before his Jewish patron and an audience, including competing poets, leading the patron to toss some coins into the poet’s purse. Yet, as Ann Brener points out, there is really no evidence for this.92 The image is undoubtedly constructed out of depictions of similar scenes in Arabic adab collections and what seem to be performative aspects of the poems themselves, such as first-person addresses, references to rival poets, and dedicatory sections. Because of the accepted view that Jews imitated the prevailing Muslim court culture on a smaller scale, not only textually but also materially, it would only be fitting that they practiced some version of public or semipublic adulation.93

Given that the courtly image is tightly bound up with the practice of panegyric—specifically, its oral recitation before a paying patron—it is worth revisiting the evidence for oral and written aspects of Andalusian Jewish poetic culture and panegyric practice in particular. It is clear that Hebrew poets sometimes met and exchanged poems and even competed to outdo one another within certain formal constraints, but we have exceedingly few anecdotes that recount panegyric performance or modes of remuneration. Some poems include specific requests for payment in the form of robes and the like, but one imagines that, had the direct payment of a poet for his panegyric before an audience been a norm, we would have at least a few anecdotes to that effect.94 Despite some justification for the type of courtly performance that Weiss and others have imagined, I argue below that the preponderance of evidence points to a mixed oral-epistolary function similar to that described with respect to the Islamic East. Overall, the social structure of Andalusian Jewry represents more of a localized and less hierarchic (yet more elitist) version of its Eastern counterparts than a break with Jewish culture in the rest of the Islamic Mediterranean.

Insofar as at least some Hebrew panegyrics were performed orally in al-Andalus, the social setting is mostly reminiscent of the majlis uns, or, better still, the mujālasa, the more egalitarian salon of the middle strata. As Samer Ali has argued, the mujālasa was forged through bonds of mutual affection and “often prompted bacchic excess: banquet foods, wine, fruits, flowers, perfumes, singing, and of course, displays of sexuality and love.”95 This practice, too, may have had at least some precedent among Jews in the East prior to the year 1000, as suggested by one of the only wine poems to survive from that environment, “When I drink it I fill it for another, who gives it to his companion, and he, too, pours [lit., “mixes”] it…. All the lovers call out, ‘drink in good health!’” (lit., “life”). The poem not only idealizes wine but also a host of social ideals of which wine is a metonym.96 Still, it was only in al-Andalus that such social practices seem to have become the emblematic pastimes of a recognizable group.

At the heart of the matter is what is meant by the word “courtly” that is so often affixed to Andalusian Jewish culture. If it means tastes for wine drinking, garden settings, and an attraction to things worldly—then the Andalusians were more courtly than their counterparts in the Islamic East.97 If it refers to Jews who held actual positions within Islamic courts, then this is a phenomenon that is well attested throughout the Islamic Mediterranean.98 If it refers to a set of intellectual values that blends traditional Jewish learning with contemporary intellectual currents (whether termed “secular” or “Islamic”), then this, too, is something we find among Jews from Córdoba in the West to Baghdad in the East. But if it refers to the political practices associated with Islamic courts—a penchant for hierarchic structures, pronouncements of rank, and an imperial perspective—then Andalusian Jewish culture might be considered less courtly than its Eastern counterpart.

Oral and Written Elements of Panegyric Culture in al-Andalus

Generally speaking, the Hebrew poetic culture of al-Andalus had strong oral components.99 Even Mosheh Ibn Ezra, who describes his own generation as a period of decline, testifies to the continued oral circulation of poetry through poetry transmitters (Ar., ruwā’; sing., rāwī). In fact, he characterizes oral transmission as superior to written recording, or at least that the latter is rendered unnecessary when the machinery of oral transmission is in place. Writing of the finest poets, he states: “I did not record any of the best poetry of this superlative group or an exalted word of their superior words, for they are well known and preserved in the mouths of the poetry transmitters (alruwā’). For the light of the morning obviates the need for lamps, and the sun obviates the need for candles!”100

A number of other pieces of evidence point to oral and even improvisational elements of this poetic culture in the generations prior to Ibn Ezra. Hebrew liturgical poems were certainly heard, and we imagine that many poems composed for weddings and funerals, which often contained praise, were recited aloud. In an epistle to his patron Ḥasdai Ibn Shaprut, Menaḥem Ben Saruq mentions, regarding laments that he had composed over the patron’s father, that “all Israel lamented [them] each day of mourning” (one presumes orally).101 As Schirmann notes, the Judeo-Arabic superscription preserved in a Geniza fragment to a well-known poem by Dunash Ben Labrat reads: “Another poem by Ben Labrat about the sound of the canals…. [here the scribe lists other subjects of the poem]. He described this at a gathering (majlis) of Ḥasdai the Andalusian.”102 Yehosef the son of Shemuel ha-Nagid relates, in a superscription to a poem, how his father improvised fifteen poems on the theme of an apple at a small social gathering (maqom ḥevrato).103 Oral recitation at a small gathering is also suggested by a superscription in the dīwān of Yiṣḥaq Ibn Khalfūn: “And he wrote to him while drinking his medicine [i.e., wine] and his friends were with him at the gathering (majlis).”104 Again, such gatherings are reminiscent of the majlis uns, or the mujālasa, and, notably, there is no evidence for the presence of a patron paying professional poets.

Abū Walīd Marwān Ibn Janāḥ presents an anecdote that highlights a mixture of oral and written elements in Andalusian Hebrew poetic culture. While a young man, Ibn Janāḥ visited the poet Yiṣḥaq Ibn Mar Shaul and tried to impress his host by reciting one of Yiṣḥaq’s poems. Ibn Janāḥ relates that he opened with the words segor libi (the enclosure of my heart) and then: “when I recited this poem before its author, he responded to me qerav libi (the innards of my heart)! I said to him, ‘I have not seen it (like this) in any of the books but rather segor libi. If so, whence this change?’ He said to me, ‘When Ya‘aqov and his sons recited this, he sent it from his city to Córdoba, and when it reached the transmitter (rāwī) Rav Yehudah Ben Hanija and with him Rav Yiṣḥaq Ibn Khalfūn, the poet had difficulty with the verse and changed it.’”105

Ibn Mar Shaul blames not the incompetent distortions of copyists but rather the intentional alterations made by the learned. Here we witness that a short poem was recited, then committed to writing, sent over a distance, and subsequently modified by a reciter whose version of the poem was copied in (apparently several) books and became the accepted standard. Transmission thus incorporated both oral and written aspects.

Ibn Janāḥ’s anecdote calls attention to what I consider one of the most crucial aspects of Andalusian Jewish intellectual society. Only rarely do we find intellectuals gathered together; for the most part, they appear separated by distances and had meetings only occasionally.106 This is the picture that emerges when reading the history of Hebrew poetry in al-Andalus as described by Mosheh Ibn Ezra. For the most part, Ibn Ezra describes an ever-shrinking constellation of intellectuals, often moving from place to place and spread out across al-Andalus. He does not describe a series of discrete Jewish courts, each with competing poets orbiting around a patron, but rather a coterie of scattered authors who exchange poems over distances. He mentions authors according to their generations, and then according to their cities, but hardly describes any organized court. The closest he comes pertains to the poets surrounding Ḥasdai Ibn Shaprut (further below), but any Jewish court culture must have been extremely short-lived; it seems to have been unique to the period of the Umayyad caliphate and was perhaps repeated, to some extent, in various Taifa states; but certainly by Ibn Ezra’s generation, there barely seems to have been a trace of stable circles organized around patrons. This is how Ibn Ezra describes the generation of poets preceding his own:

Among the poets of Toledo were Abū Harūn Ibn Abī al-‘Aish, and after a period Abū Isḥāq Ibn al-Ḥarīzī. Among the poets of Seville were Abū Yūsuf Ibn Migash, originally of Granada and later of Seville, and Abū Zakariyya Ibn Mar Abun. And among the last of the generation in Granada was Abū Yūsuf b. al-Marah. Among the people of firm speech and clear poetry was my older brother Abū Ibrāhīm; he, may God have mercy on him, possessed gentle expression and sweet poetry due to his fluency in knowledge of Arabic expression (‘arabiyya). He died in Lucena in 1120/21. And in the east of al-Andalus there was at this time Abū ‘Umar Ibn al-Dayyan…. How deserted the earth is after them! How dark it is for their loss! Thus it is said, “The death of the pious is salvation for them but loss for the world. Our ancestors preceded in this with this saying, “the death of the righteous is good for them but bad for the world” (b. Sanhedrin 103b).107

Regarding his own generation, Ibn Ezra continues:

Those of their generation who are at the end of their days, and those who come after them and follow in their paths, are an exalted small group108 and a beautiful coterie that understands the goal of poetry. Although they were adherents of different schools (madhāhib) and [attained] distinct levels of speech, they came to [poetry’s] gate and path, administered its purity and eloquence; they reached the extreme of beauty and splendor, nay they were mighty in likening and similitude. It has been said that men are like rungs of a ladder; there are the high rungs and the low and those in between. But all of them, in whatever cities they dwelled, were in the circle of beautifying, precision, and mastery.

He goes on to mention numerous figures by name, several of whom had migrated from one city to another, and concludes: “These skilled people (naḥarīr), I met all of them (except for a few) and selected their most famous and obscure [verses]. The poet [Abū Tammām] said concerning this, ‘The coterie (isāba) whose values (adābuhum) are my values, though they are apart in the land, they are my neighbors.’”109

These intellectuals constituted a group largely by virtue of the literary and other intellectual ties maintained among them. If I might be permitted some anachronism, Andalusian Jewish courts were largely “virtual” and owed their existence to a web of connections and occasional moments of encounter. In Chapter 2, we will consider the role of panegyrics exchanged throughout such networks as “gifts.” For now, we will continue to review the evidence for the oral and written elements of panegyric practice in al-Andalus.

A small subset of Andalusian panegyrics seems to be associated with installation to office or some other public acclamation of power. The most suggestive examples I have identified emanate from the dīwāns of Mosheh Ibn Ezra and Yehudah Halevi.110 One of the poems by Ibn Ezra bears the superscription, “To a friend who was appointed to the position of judge (tawallā al-qaḍā’)” and includes verses that suggest a political ritual:111

All the masters of knowledge testify that your community adorned and elevated itself through you.

[Your community] became your subject today, it inclined to be ruled by your decree.

[Your community] raised up the wonder of dominion [before you] for it is your possession and an inheritance from your fathers.

They said to you, “You are next in succession, come and redeem your inheritance!

Arise and be our judge112 for we have not found a leader113 like you.”

Make a pledge with the sons of Wisdom for they, among all men, share a pact with you …

Take delight in the might of the world but also beware lest it seduce you….

This is advice from a friend whose soul takes pride on the day of your pride’s exaltation.114

The immediacy of an occasion is suggested by such words as “today” and the second-person address to “arise and be our judge.” The references to a “pledge” and “pact” likely allude to standard practices of Islamic installation rites, which center on the loyalty oath (bai‘a) and making a bilateral compact (‘ahd).115 The poem was certainly written for the occasion of the friend’s installation, though we do not know that it was recited as part of the ceremony; as is often the case, we are forced to rely upon the internal evidence of the poem, a method that can be only partly successful because poems that were not performed can contain performative elements.

A second example from Ibn Ezra’s dīwān is a panegyric in strophic form, written, it seems, for the induction of another judge,116

How comely on the mountain are the footsteps of the herald announcing (Is 52:7)

that a shepherd has come to bring comfort to the flock wandering in the forest.

Behold, the sound of the people in its boisterousness (Ex 32:17) is heard calling him in song.

Our rejoicing before you is like the joy of a multitude on their holiday.

May you reign over us! You and your son and your son’s son!

Gates of the House of God, lift up your heads and say, “Come, O blessed one of God!

The one who stands to serve by the name of God, to teach the law of God,

to teach the teachings of God that [they] may know the ways of God.”

For these are a sign upon your right hand and a reminder between your eyes (cf. Ex 13:9).

Although the unprotected settlements117 are no more, you restored their habitations!

Although prophecy and vision had grown rare, you spoke their wonders!

Although deprivation had wasted their souls, your wisdom revived them!

Your table satisfies them, your refreshing stream gives them drink.

From now on you will be minister over one thousand. May you be exalted and rule over Israel!

May your enemy pass away, may he be lost and not be redeemed;

God has unsheathed His sword against him, but you he has chosen like Ittiel [i.e., Solomon].

May a thousand fall at your left, ten thousand at your right! (Ps 91:7)

May your name be exalted and magnified in all the corners of the earth!

May you wipe out transgressive and iniquitous people and burden their yoke!

May you judge them by the laws of the Torah and teach [the laws’] general and specific principles!

May your tongue utter wisdom and God illumine your face!

Again, several elements suggest a ritual occasion: the boisterous singing, the blessing of welcome, and the words “from this day on.” Again, we do not know that this poem was uttered within an initiation ceremony, but it seems likely that there was some sort of ceremony that involved the singing of songs. Unfortunately, we still know very little about the performance of public rituals among Andalusian Jews. It seems that there was at least some continuity with Jewish rituals of installation as known from the Islamic East, and in both locales we find parallels with contemporary Islamic rituals of power. However, the installation of a judge in al-Andalus was a less “imperial” occasion than the appointment of an exilarch in Baghdad. In any case, there is no reason to believe that this poem was commissioned by a paying patron.

As stated, the most likely testimonies for Jewish panegyric performance on a courtly model pertain to the brief period of Ḥasdai Ibn Shaprut. Mosheh Ibn Ezra writes concerning Menaḥem Ben Saruq and Dunash Ben Labrat that Ibn Shaprut “rejoiced at their wondrous poetry and their marvelous and eloquent addresses.”118 In all likelihood, at least some of these poems were the panegyrics for which these poets are known.119 Yet many panegyrics were clearly not performed face-to-face by the poet before his mamdūḥ, such as one that Ben Saruq sent to Ibn Shaprut when the former was imprisoned by the latter.120 Nonetheless, the poem presents elements of “performativity” we might expect from formal courtly performance such as first-person speech and a boast over poetic skill.121 In the final verse of the poem, the poet captures the rhetorical function of the address, which is to assuage the anger of the mamdūḥ and to gain freedom, a purpose masterfully developed through the rhetoric of the appended letter. Was the poem recited by a rāwī subsequent to its reception before the mamdūḥ alone, in a small social gathering, or in a public assembly? Oral performance remains a possibility, but we have no evidence one way or the other. What is certain is the poem’s function as part of an epistolary package.

The most extensive anecdote that we possess concerning the performance of a panegyric paints a picture quite different from that of a poet presenting a poem before a patron with the hope of remuneration. Yehudah Halevi, in a letter to Mosheh Ibn Ezra, recounts how he came from “Seir” (Christian Iberia) to “dwell in the light of the masters of great deeds, the great luminaries, the wise men in the west of Sepharad (al-Andalus),”122 who ultimately befriended him. Recalling their generosity, he wrote: “Time took an oath not to make an end (of me) but in the house of my estrangement it sustained me, delighted me with songs of friendship, and satiated me with the wine of love after I had sworn to wander.” The company was reciting a poem by “the prince of their host,” Mosheh Ibn Ezra (who was not present), a panegyric in honor of Yosef Ibn Ṣadīq in muwashshaḥ form that concluded with an Arabic kharja, titled “Leil maḥshavot lev a‘ira” (A night when I rouse the thoughts of my heart).123 After the others attempted to imitate the poem but failed, Halevi invented a complete version (presumably orally), which he later memorialized in the letter.124 In Halevi’s version, it is now Ibn Ezra who is appointed the mamdūḥ.

What do we learn about the place of panegyric in Andalusian social culture through this anecdote? First, we learn that Ibn Ezra’s panegyric to Ibn Ṣadīq circulated beyond the hands of its recipient; it was likely sent to Ibn Ṣadīq and then copied or circulated orally to others.125 Halevi’s letter might be alluding to some of the social practices associated with court culture (wine, music, poetry), particularly the majlis uns, and the reciprocity of the social relations recalls the mujālasa most directly. The oral recitation of poetry, including Ibn Ezra’s panegyric for Ibn Ṣadīq and possibly other panegyrics (perhaps suggested by “songs of friendship”) is clearly attested.126 However, to the extent that Ibn Ezra was the “prince of their host,” he was not actually present; there was no patron in the sense of one receiving praise and offering payment in exchange. Halevi also created a panegyric without the mamdūḥ’s being present, a poem that he subsequently sent within an epistle. What did Halevi want from Ibn Ezra in sending him the epistle embedded with the poem? The answer, quite simply, is recognition, association, protection, and possibly even financial support. However, he was not seeking quid pro quo cash remuneration but something much broader, the dynamics of which we explore further in Chapter 2.

While scholars often cite this anecdote in order to capture Halevi’s remarkable skill and rise to fame, here I stress the social dynamics revealed. The poem, after all, was not any old muwashshaḥ but one dedicated to Ibn Ezra’s honor. The events that Halevi describes might be viewed as a pretext for directing praise toward Ibn Ezra. The letter is essentially a “self-introduction” written in the hopes of formalizing a relationship. Praise is the expected rhetorical register for doing so and is highly attested both in the introduction to the letter and in the poem that it contains. It is possible that Halevi’s poem was recited aloud after reception, but we do not know this with certainty. This turned out to have been the beginning of a beautiful friendship, as Ibn Ezra responded to Halevi’s letter with a poem inviting the young poet to Granada. The poem praises the eloquence of Halevi’s letter and the poem that it contained and reflects astonishment at the author’s prowess despite his youth. On the other hand, Ibn Ezra’s response did not praise Halevi himself; the poem is a type of panegyric sent from an older and more powerful “patron” to a younger and less powerful “client.” The poem employs only circumscribed praises and thus defines the formality and vertical dynamic of the relationship during its formative stage.127

* * *

In discussing Jewish panegyric in the Islamic East above, I pointed out that many poems held a specifically epistolary function. The same is true of many poems from the Andalusian corpus. An important example is the poem “Afudat nezer,” written by Menaḥem Ben Saruq as the introduction to an epistle on behalf of Ḥasdai Ibn Shaprut for Yosef, king of the Khazars. Adopting monorhyme (a standard feature of Arabic prosody), the poem opens with the kinds of blessings that one would expect in an epistle proper:

May the priestly crown [be given] to the tribe that rules the far-off kingdom,

May God’s benefit be upon it and peace be upon all its governors and host,

May salvation be a raiment upon its shrine, its holidays and sacred occasions.