Читать книгу Two Owls at Eton - A True Story - Jonathan Franklin - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеWhen I was ten, I could tell you the wingspan and the colour of the eggs of every bird in The Observer’s Book of British Birds. I would wander up and down Suffolk hedgerows collecting birds’ eggs (today quite rightly that is illegal); only one from a nest was the rule. I would blow the yolk and white out and fry them up with fresh eel that I’d caught in a tidal pond beside the River Deben. Scrumptious.

I thought of myself as a budding ornithologist and leapt at the chance to look after a wounded bird or an abandoned fledgling. My first effort was to make a splint for the broken wing of a black-headed gull that I found in Kensington Gardens. I had to force feed it, but it died within three days. I knew I had to improve my technique.

By the time the heroes of this book, Dee and Dum, arrived at Eton, I had nursed a thrush, a jackdaw and a pigeon, and kept a baby rabbit, brought in by our cat, in my bed while I was recovering from flu.

But it was owls that fascinated and especially tawnies: the silent flight, the sharp, mysterious hooting, the soft brown plumage and the extraordinary swivel-like turning of the head. Examining a dead tawny, I was intrigued by the size of the eyes and the long semicircle of a hidden ear on each side of the flat round head. An ornithologist friend of mine told me that the eye socket of an owl takes up more than 60 per cent of its skull whereas ours takes up a mere 5 per cent, and that the design of a stealth bomber’s wings owes much to detailed appreciation of owls’ wings.

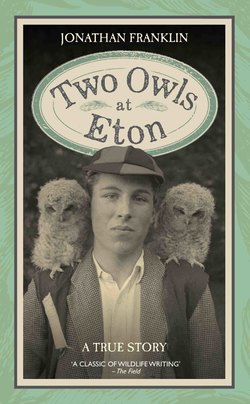

Dee and Dum, lucky to be alive, arrived at Eton in a simple cage and were adored by everyone who met them. I was sixteen. We grew up together in that summer of 1959.

*

I went to Eton because my father played cricket with my House Master and my mother knew several mothers of Etonians. In those days Eton was not the target of constant, global media attention but rather the object of mild curiosity; calling a term a Half, wearing formal School Dress in remembrance of George III and playing games like the Field and Wall games that no other school played. I arrived in my tails and white tie at just thirteen and, I admit, scared stiff. Discipline was rumoured to be fierce: Beating, Swiping, Tanning lay in the shadows ready to jump out. I felt utterly insignificant, surrounded by tall, elegant buildings, their walls hung with ancient pictures and tapestries. For the first few days I walked, head down, as if along an endless passage hemmed in by high walls where I couldn’t see over the top and where to go.

At the time, the press was full of news of distant wars; the Suez Crisis and the Hungarian Uprising. We heard that an old boy from our house had been killed in the Malayan Emergency. My peer group of boys came from varied backgrounds, and there were some whose fathers had been killed in the Second World War. There were masters who had served – one had been a Lancaster bomber pilot, another a prisoner of the Japanese and because his neck was rather long we nicknamed him Rubber Neck as we imagined he had been stretched on a rack. We wondered whether we’d be called up when we left school. Some rather relished the prospect of banging about with a .303. Fortunately, Elvis was rocking out ‘Hound Dog’ and ‘Blue Suede Shoes’.

I would walk up Eton High Street with a friend on the way to Agar’s Plough to find a tree for Dee and Dum to clamber about in. No one thought it particularly strange that a boy should wander around school with a couple of owls on his shoulders. Duff Cooper once said that Eton allowed eccentricity and encouraged boys to follow their passions. How true.

I wrote this book at the suggestion of John Pudney of Putnam’s. He had read my article about the owls in the school’s Natural History Society magazine. He asked for a couple of chapters. He liked them and there I was writing a book. My House Master, Bud Hill, let me write by candlelight after Lights Out for two nights a week; amazing for a House Master who confiscated our longed-for Valentine cards, and equally surprising that both he and my parents let me spend so much time on such an ex-curriculum activity in my A-level year. My indifferent results were probably due to the attention my feathered babies demanded as they scuffled around my room and teased at my pen with their talons, resulting in even more incomprehensible French than usual.

Apart from the absorbing interest in writing this book while still at school, I savoured my last year at Eton. School Library and College Library were magnets and I would admire the spines of rare books and occasionally dare to pull one out. In the evenings I would go to meetings of several of the school societies. There was a freedom to pursue your interest without influence or interference. Even so, every morning all Upper Boys had to assemble in that gem of European architecture, College Chapel, for the master in charge to make sure that no errant boy was larking about in London. The Precentor played Bach on the huge organ. Such is the strength of that organ that rumour has it that playing with all stops out helped to shake out the remaining shards of coloured glass from the stone window frames after a bomb had landed nearby during the war. I felt very very lucky.

*

This book was published in November 1960. Five extracts were serialised in the London Evening Standard. But still I was amazed to see a huge coloured billboard showing Dee and Dum in full flight on the paper’s sales stand at the crossroads in the High Street.

I am sure that I walked past pink in the face and was probably mobbed up mercilessly by my friends. Within a fortnight we were in the Evening Standard’s Top Ten bestseller list. The week before there had been extracts from a biography of Lord Curzon and one critic expressed his relief that memories of that ‘Most superior person’ had been fluffed away by a couple of birds! The next day a girl I’d always fancied wrote saying that she’d just walked past Liberty’s in Regent Street and that a whole window was dedicated to my book, with at least three hundred copies on display. I hoped that my chances might improve with her. But no, Dee and Dum didn’t win on that one.

I was to leave Eton for the last time that Christmas. Robert Birley, the Headmaster, asked me to lunch. He said that Dee and Dum had done more good for the school’s image than any other recent publication. That, certainly, was worth a bonus mouse for Dee.

And then BBC Look East rang wanting a live interview. I drifted about in a haze of incredulity with no idea of the fame that was about to hit Dee and Dum. Even Walt Disney played with the idea of an animated cartoon. Often a well-meaning hostess at her daughter’s coming-out party would insist that I sat beside her to talk about owls; whereas all I wanted to do was to be next to her daughter as a prelude to the last dance of the evening, hopefully cheek to cheek.

Often as I walked to work down the King’s Road in London, there would be a pat on my shoulder and a friendly greeting of, ‘Hello, Owls. How’s life?’

And then I left for France and on to Brazil. But owls didn’t forget us. Often, at my mother’s house in Suffolk, a cardboard box with no message, just a plain box, would be on front doorstep and we’d know what was inside: one, two and even, once, three baby owls. We’d become a safe haven for distressed owls. Over fifteen years we nursed and released between eighteen and twenty abandoned tawny and barn owls.

Even in Brazil, owls refused to forget me. I was given two immature least pygmy owls. Tiny little chestnut, yellow-eyed, fierce predators, no bigger than my fist, that live in burrows. An armadillo had probably wrecked their nest. I spent hours with them but failed to make friends, and eventually and very sadly they died of bad chicken heads from the local butcher because I’d run out of fresh sparrows. I was devastated at my failure.

*

Today, I understand that, due to the fame of Hedwig, the owl in the Harry Potter books, perfectly healthy owlets are taken from their nests to be somebody’s Hedwig. I expect many die within days. I implore that this book does not encourage any such robbery. Owls are wild animals and we must do our best to protect them, especially in these times of intense agricultural practices. To look after an owlet is a full-time job. You can’t leave one in a room and expect it to be happy. If you want to help, put up owl boxes. They are effective. Every owl that my mother and I brought up was an orphan or damaged, and our object was to get them back into the wild as soon as possible.

On a balmy autumn evening, with a glass of wine to hand, I sit in the garden a few yards away from where Dee and Dum began to gain enough confidence to return to the wild. I listen with pleasure to the shrill hooting and sharp squawks as the descendants of Dee and Dum (as much Old Etonians as George Orwell and Prince William) squabble with their children and shoo them out, as parents are wont to do.

SEPTEMBER 2016