Читать книгу Two Owls at Eton - A True Story - Jonathan Franklin - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Arrival

ОглавлениеFrom yonder ivy-mantled tow’r The moping owl does to the moon complain.

THOMAS GRAY ‘ELEGY WRITTEN IN A COUNTRY CHURCHYARD’

THE PORCH OF Debenhams in London’s Oxford Street was filled with a crowd of people; all eyes were fixed on one object. Little did I know that the centre of their attention was my pair of owls in their cage. There they were, squatting on their haunches, quietly contemplating the chattering mass of onlookers. I pushed my way through, excited at the thought of seeing them for the first time for two weeks.

It all started one day late in April when a friend rang me up to tell me he had a nest of tawny owls in his garden; would I like one? Apparently the mother had been shot by a gamekeeper and there were some young orphans left. It annoyed me very much to hear this, as the constant massacre of owls is pointless; they do incomparably more good than harm. On the other hand I was excited to hear about the babies, because owls have always fascinated me. Not thinking of the complications involved, I immediately said ‘yes’. This one word changed the whole routine of my life for a good year.

The nest was in a hollow tree and held two babies. I immediately broached the subject of having them with my parents, who were decidedly against the idea. Who, they asked, would look after them when I went back to school in a week and they had to leave for the Continent? I suggested Susan, our gardener’s daughter. There was no reply to this idea except a quiet ‘Poor thing’ from my sister. However, I knew the answer was ‘no’.

The subject arose again at breakfast with my father, as I thought that if I could persuade him, my animal-loving mother would soon agree. The argument waxed hot and tempers rose. I kept saying that we could not let them die and must save them and bring them up. Then, I had the brainwave of taking the owls back to school with me. They were very small and could not possibly cause any trouble. This complicated the issue rather than simplified it and remarks such as ‘Never heard of such a thing, owls at Eton!’ were frequent. My father is not at his best at the breakfast table. However, a temporary arrangement was reached. I must write to M’Tutor (that is, my House Master) and ask him if I could bring them back to school. If he said yes, wonderful, if no, I hoped Susan would take on the job of nursemaid for me, as she is very fond of animals.

I did not write the letter until two days before school began, only just leaving time for a reply to arrive on the morning before I left home. Meanwhile I collected the owls from their tree fifteen miles away, helped by a very kind friend, Mrs Hawdon. We both went armed with leather gloves and scarves to protect our eyes, as I had read that owls in the mating season are more courageous than any hawk.

I found the hole was just within ladder height and climbed up. Peering in, I could see two small balls of fluffy white down. They seemed to consist only of stomachs and mouths and into these, although the owls were only the size of tennis balls, I could insert my thumb. They were lying in a makeshift nest of old pellets and bones, surrounded by dead rats and mice.

When owls catch their prey – rats, mice, voles, moles, baby rabbits and the occasional fish taken on the surface – they do not necessarily eat it immediately but put it beside their nests. This is a useful habit, as in winter food can be scarce for days on end and so the hungry owl can then resort to this reserve. These stored animals are often decomposed but an owl will eat almost any rotting food.

As I looked at them, I felt very doubtful whether I could hope to rear babies so young; they were only three weeks old. But when the larger, sensing my presence, turned towards me and gave a loud click with its beak I could not resist the temptation to pick them up and put them into a cloth-lined box.

The journey home was uneventful and the owls lay quietly in their box. They were the ugliest baby creatures I had ever seen and at first I felt disappointed. Their heads were one and a half inches in diameter, with two red slits where the eyes were eventually to appear, and an enormous opening which was the beak. The head and body, connected by a thin neck, were covered with a sparse layer of white fluff. They had only tiny stubs of flesh for wings and little white immature legs. Unable to walk, they were completely helpless. They were only capable of opening their mouths, clicking their beaks and making raucous cries, which they did whenever I lifted the lid. I am convinced it was not for fright and more likely for food as they were still blind.

The first problem when I arrived home was food. I had read The Observer’s Book of Birds, and other books, and all said that owls eat rats, mice, etc. But I had been told that baby owls are given the insides of animals until they are old enough to eat fur and feathers, which are roughage for them. That night I fed them with plain horsemeat and halibut oil and put them in the airing cupboard in the kitchen, which I thought would keep them sufficiently warm. As I put them into the cupboard our housekeeper turned to me and said, ‘Won’t they cook?’ For a moment I was horror-struck as the thought of cooked owl for breakfast flashed through my mind, but I soon remembered the many other small birds who had started their recovery in our airing cupboard. I went to bed that night thinking what horrible, ugly little beasts my future pets were.

At six o’clock next morning they were ravenous. Beside the larger of the two lay a small round ball of fur and feathers, the technical name of which is a ‘pellet’. A pellet consists of undigested particles of food, bones, feathers and fur, which are separated from the flesh by an iron-hard stomach that nature has placed below the breast-bone, not above as in the case of the crops of other birds. These pellets are regurgitated at twelve-hour intervals and vary in size according to the amount the bird has eaten. My owls produced quite small ones, from one and a half inches long and a third to half an inch thick, because they had more boneless food than wild owls. The pellets of wild owls can be over two inches long and half an inch wide. I once found one with three mouse skulls in it.

I had heard of one or two cases where people keeping owls had lost them due to what I thought was a bad diet and in particular not enough roughage to produce pellets. My biology teacher said that these pellets are of vital importance to an owl, because in its stomach there would be a strong secretion or enzyme that helps to break up the bodies of their prey, and unless this secretion is disposed of through a regular pellet and not left unused in its stomach, it could paralyse and eventually kill. In the wild this presents no problem, as owls only eat furred and feathered creatures. I was terrified lest anything like this should happen to mine, so I immediately started covering the meat with feathers and fur. I also set five mouse traps, and caught six mice, two in one, side by side!

While I was preparing the food, I noticed that the bigger of the two was pecking at his brother, who was now quite still. Very soon I realised that this pecking was no affectionate caress, but plain cannibalism! The other owl woke up and proceeded to try to eat his brother also. The only explanation possible is that in their blind state they mistook each other for food. This habit lasted until well after their eyes had opened; it must therefore have been due to a lack of brotherly love! Meanwhile the day for returning to school was approaching and the time for an answer from my House Master. In case of a refusal I prepared everything for Susan; pages of instructions, clean bedding, mouse-skins (as we gave only the skins at this stage), horsemeat, liver as their main food, tins of chicken pellets, and a bottle of precious halibut oil which I felt was life-giving to them.

I started feeding them chicken pellets when I saw a sack being taken to the chicken-house. On it was written ‘Extra Vitamins’ and so after that I gave them some Spillers Chick Crumbs. I hoped these would fight off any possible paralysis that I’d been warned about, due to lack of vitamins. I soaked the crumbs in water and made them into soft lumps. They smelt revolting, but the owls ate them up readily enough.

The fateful morning arrived and with it no return letter. I had not given my House Master enough time to answer. And so with a heavy heart, as I had already become fond of my ugly companions, I left them in Susan’s hands. The letter arrived by the afternoon post just after I had left home and when I arrived at Eton M’Tutor immediately asked me where the owls were and if they were all right!

For the next fortnight I did not see them but was assured that they were in good health by frequent letters from Susan. In my anxiety I wrote frantic letters asking for news and giving instructions which were either impossible to carry out or quite useless. I wrote continually to find out if they had made a pellet, as I was frightened lest they should die. Each letter said, ‘Put more feathers on the meat, put more fur on, for heaven’s sake. Please watch day and night to see if they produce one.’ Each reply letter was the same, ‘Sorry, I am afraid there is no pellet yet.’ By the end of ten days I had sent five letters and was indeed in a state of desperation, knowing that the next letter would bring news of a pellet or of death.

One morning there was as usual a letter lying on my breakfast plate. The address stood out clearly, ‘J. M. Franklin, Esq., Corner House.’ I picked it up with trembling hands and tore it open. There was one line, ‘I found a pellet this morning’!

Susan kept the owls in a cloth-lined box in an airing cupboard and fed them at regular intervals, in spite of her having to go to school. Feeding times were: 7.30, a large breakfast; 10.30, a light meal, given by Susan’s mother; 12.30, a large lunch, given by Susan; 3.30, a light meal; 7, another meal and 10.30, a large supper to last them through the night.

The food was mainly horsemeat covered with pigeon feathers or fur, pieces of mice and a little liver, plus one drop of halibut oil each per day. They were given as much as they could eat and as a result grew tremendously. In two weeks they were twice their former size. Their appetites were enormous and in a week they consumed half a pound of horsemeat and a quarter of a pound of liver, to say nothing of the many mice which were trapped every day.

When the owls were fed, the food was prepared first and put on a plate. They were seated on the table on their behinds with their feet out in front and heads up like begging dogs. At first they rolled over but soon their legs strengthened and helped them to keep upright. Also, their stomachs were so big and protruded so far that they hardly needed other help. The food was put down their open mouths in small bits. Water was squirted down once a day from an eye-dropper.

Very shortly they outgrew their box and began to wake Susan up in the morning with their beak clickings and raucous cries and so they were transferred into an old budgerigar cage. Susan put this in the kitchen and they spent the day either sleeping or watching with intense curiosity every movement made outside their cage. They would sit motionless and follow the object of interest through its entire course by turning only their heads and watching with unblinking eyes like two old women. Owls cannot move their eyes, only their heads.

Their limbs soon began to strengthen and they began to walk and climb. When climbing they clambered up the side of the cage. This exercise would take anything up to a quarter of an hour. When it reached the top, the owl, unable to think of a means of descent, would loose its grip and fall to the ground with a sickening thud, where it would lie struggling on its back. Shrieks of laughter would come from Susan and her sister Doreen, whereupon the owl would give a convulsive jerk and right itself and then gaze at the source of noise until the laughter ceased. When it did, the climbing would start again. It would go on until both owls were so exhausted that they fell asleep.

After two weeks of the half, i.e. term, I broached the subject of having the owls at Eton to my House Master again. Fortunately he did not object, and very soon I had a plan to bring them to school.

I managed to arrange a dentist appointment in London, when my friend, Mrs Hawdon, would be going there as well. She agreed to bring the owls with her and we fixed the meeting place to be in the hall of Debenhams, as it was near my dentist.

Mrs Hawdon fetched the owls from Susan, put them in a large mouse-cage, 2 foot 6 inches by 1 foot 6 inches by 1 foot 6 inches, and caught the train to London after a restless night, as the owls had decided to spend it pecking the wire of the cage. On the train she sat proudly beside her charges and fended off all questions. However, halfway to London she had to leave the carriage to have her breakfast. Returning, she found a crowd of people in the corridor with one man gesticulating wildly and nursing a finger. With his other hand he was pointing menacingly in the direction of the cage. My friend pushed her way into the compartment, fearing to find the owls carried off as a danger to the public but she found them fast asleep. After much shouting and indignant protest from the wounded man, the story unfolded itself. This man, fancying his influence over animals, had approached the cage, and with cooing noises had tried to stroke one of the owls. The owl, however, feeling hungry, mistook the finger for a worm and, grabbing it in his beak for all his worth, refused to let go until the man pulled it out by force. Eventually tempers calmed and, nursing his injured finger, the man left the train, vowing never to try to make friends with owls again.

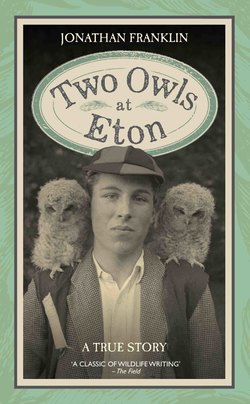

On arrival at Debenhams, the cage was placed in the porch and Mrs Hawdon sat patiently beside it until I should arrive. I arrived five minutes later, to find a large crowd already assembled. I forced my way through the crowd and, without paying any attention to my friend, such was my hurry, knelt down beside the cage and gazed at its contents. The owls were twice the size they had been when I had left them two weeks before and were now alert and attractive to look at. They had grown new downy feathers which were light grey in colour with stripes of dark grey and brown.

The next stage of the journey entailed getting them to Waterloo Station from where I could catch a train to Eton. I hailed a taxi, while Mrs Hawdon and the commissionaire brought out the cage and the boxes of food. As the taxi drew up I said to the driver in a merry voice, ‘You don’t know what you’re taking on, old chap.’ He looked at me faintly bored and then stiffened as he saw the commissionaire advancing with the cage. ‘That isn’t coming in here, is it?’ he asked, scowling at me. ‘Oh, yes, it is,’ I replied as I bundled myself and the cage into the taxi, at the same time thanking and saying goodbye to Mrs Hawdon. Then turning to the driver I told him where to go. Before I had finished, the taxi was bounding forward down Oxford Street with the driver bent over the wheel and his accelerator hard down.

It was the fastest taxi drive I have ever experienced. Every now and then the driver would look over his shoulder, possibly expecting me to turn into an owl at any moment. As I paid him off at Waterloo, I thought I saw drops of sweat on his brow but perhaps it was only my imagination!

I picked up the cage and held it at arm’s length so that I could just see over the top and walked up the steps towards the suburban lines. At the top I marched firmly forward, but hardly had I gone five paces when I saw something which made me stop dead in my tracks. Walking towards me, ten yards away, were the two most august dignitaries of Eton: Provost Elliot and Vice-Provost Lambard. My blood froze and I remained rooted to the spot. Perhaps they would recognise me and put a stop to my plans then and there. I looked around for a place to hide. Behind me I saw a flight of dirty steps, down which I scurried like an overloaded burglar escaping from the police. I found myself in one of those palatial marble halls of the Victorian era, usually described as Gentlemen’s Cloakrooms. In spite of the surroundings I put the owls on the floor and stood gasping for breath.

Five minutes later I emerged, rather cautiously, to find that the dignitaries were no longer in sight. I walked up to the timetable, put the owls on the ground again and started to look for my train. As I was doing so I heard various comments from behind, ‘Oh, aren’t they sweet!’ ‘The little darlings!’ ‘Oh, the poor things!’ ‘Are they chinchillas?’ Somewhat embarrassed, I walked past a sleepy-looking ticket-clipper so fast that he could not see what I was carrying, climbed into the nearest carriage and sank into a corner, thankful to be away from the public gaze at last. Fortunately there were only two other people in the carriage, one in the middle of each side.

My peace of mind was short-lived.

I noticed that both the other occupants seemed to be getting further away from me. Sure enough, there they were, slowly edging away until they had reached the furthest possible distance from my owls. There, in truly British fashion, they pulled out their evening papers and became immersed in them. I felt hot under the collar; surely they did not think I was mad?

This train was a rush-hour train, but nobody else came into our carriage. Occasionally, somebody would stop and look in, but they always passed on. When the whistle went, however, about six people rushed in all at once. I ignored them and looked at my owls properly for the first time.

Their eyes, now open, were big and a bluey dark brown, but there was still a red rim around the eyelids. The eyelids and eye cavities were covered with minute, very thin feathers. Their heads and bodies had thick grey-brown downy feathers becoming darker towards the roots with dark brown streaks, making a highly complicated pattern. The wings and tails were almost non-existent; the tail being smothered with downy feathers only half an inch long. The wings were feathery arms with a few primaries just peeping through on the last point. Their legs were beginning to put on the characteristic trouser feathers and had grown considerably, but still did not have enough strength to support the whole weight of their bodies for any length of time.

At first they lay placidly on their stomachs in the cage, but after a short time they began to show some signs of movement. Every so often one of them would rise manfully to its feet and walk slowly across the cage. This it did in a horizontal position with its eyes looking at the ground and legs working frantically behind. The inevitable was bound to happen. After three or four paces the owl would fall flat on its face, legs poking out behind. A violent struggle would ensue, in which legs and wings were thrown in all directions until it realised all was hopeless, whereupon it would close its eyes and try to sleep. Then, either from curiosity about its surroundings or enthusiasm to learn the art of walking, in a few minutes the eyes would open again and the head would rise, turn completely around through 180 degrees, and look at every object in turn. This manoeuvre was carried out with the rest of the body still flat on the ground and quite motionless. After this, the owl would decide to struggle on to his behind again, and the whole proceedings would begin all over again.

After a quarter of an hour I noticed that all the passengers had stopped reading; all eyes were riveted on the two fluffy objects, which now looked like proper owls and were very pretty. For the rest of the journey there were eight owl-worshippers, including myself, loving these charming and comical creatures.

My arrival back at my house was heralded with cheers and shouts of, ‘Hello, Owlman,’ and suchlike. Everybody rushed up to my room and began to maul my poor birds in such a manner that I was surprised they survived. They had gone down well with my friends, but my main anxiety was the opinion of my House Master, Mr Hill.

He heard about them on his goodnight rounds. ‘Oh, sir, have you seen Franklin’s owls?’

‘What?’ came the reply. ‘He hasn’t got those things, has he?’ and immediately he strode up the stairs to my room.

I heard his steps coming down the passage and prepared for the worst. My door burst open.

‘Where are your owls?’ he asked quickly. I pointed gingerly at the innocent and unsuspecting owls.

‘Oh! Aren’t they sweet!’ he exclaimed and kneeling down he began to scrutinise them. After a short time he stood up.

‘May I get my wife and daughter to come and see them?’

‘Of course, sir.’

A quarter of an hour later I was left assured that there would be no complaints from M’Tutor and his wife; their hearts were won. I have had only encouragement and great interest from M’Tutor, although there have been some troublesome moments.

That night I fed them on the food provided by Susan: hare’s ear, horsemeat and pigeon feathers and halibut oil. I put them to bed on a cardboard sheet in their cage with no cover over the top. I went to bed confident that the owls and I would sleep the sleep of the exhausted.

But the owls had different plans for that night and their newfound master. After an hour or so, at about eleven o’clock, they began to pace up and down, scratching the cardboard with their claws and creating a nerve-racking noise. Not content with this, one decided to peck the wire. Finding it gave out a pleasant noise, he immediately gave it violent tweaks. The other soon began merrily to accompany his brother. The noise was ear-shattering and sounded like an enormous out-of-tune double bass. I jumped out of bed and made the owls lie down. This had no effect. As soon as I was in bed the noises started up again, both twanging and scraping. I screamed some unprintable word and there was silence, this time for about fifteen minutes, at the end of which the awful twanging started again. For the next hour I shouted abuse at them at regular intervals and came to the conclusion that my owls were musical.

When finally sleep came, I was so content to have my owls at last with me that I gave no thought to the difficulties and also the great hilarities that would arise in my efforts to keep them alive over the following few weeks.