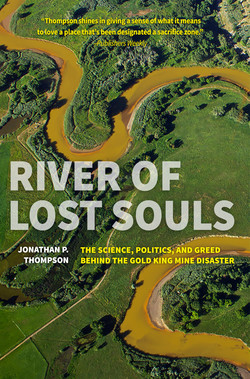

Читать книгу River of Lost Souls - Jonathan P. Thompson - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHoly Land

The farmers along the Animas River are sitting down and permitting the waters of that river to be so tainted and polluted as that soon it will merit the name of Rio de las Animas Perdidas, given it by the Spaniards. With water filled with slime and poison, carrying qualities which destroy all agricultural values of ranchers irrigated therefrom, it will be truly a river of lost souls.

—Durango Wage Earner, 1907

I’M MAYBE SIX YEARS OLD and it’s June, just after the first cutting of hay, so that pungent aroma still lingers in the early afternoon air as we walk down past my grandparents’ milk barn and the hay barn and through the dank human-sized culvert that passes underneath the new highway, which isn’t so new anymore but that’s what we call it anyway.

“Maybe we can find some asparagus,” I say, darting toward the fence.

“It’s too late,” my dad says, his voice deep. “All gone to seed.”

So I pick butter and eggs—yellow toadflax—instead, bunching a bouquet up in my little fist, no idea it’s some sort of noxious scourge, already overrunning the Animas Valley. We’re going down to the Sandbar, which is what we call the place on the river below the Farm where we fish and picnic and camp. Used to be, all the farms stretched to the river and beyond, but the new highway sliced all the old homesteads in half, so a lot of the fields down below went fallow. Then my grandparents retired and sold off the lower part, anyway, but the new owners still let us go down there so it makes no difference to me.

We called it the Farm because back then it was a farm—that’s how my grandparents made a living. They had dairy cows and sheep, they had fields of hay. They had rows of corn, apple orchards, peaches, strawberries and raspberries, spinach and lettuce. What they didn’t eat, they sold. My mom and her sisters, hair in ponytails, picked raspberries for a nickel a quart and folks would come by on the old road on their way back up to Silverton and pick up some of the bounty.

The valley floor here is wide and flat. The glaciers pushed all the rocks downstream or ground them into coarse sand, so the river runs slow here, meandering between steep and sandy banks, nearly twisting back on itself at times like a giant, murky green umbilical cord. In the spring, when the water’s big and red and brown, listen and you might hear it eating its way through the soft earth. At the Sandbar, the banks were softened into a beach by the current. As we get close, I run off ahead of my father and brother. I take off my shoes. The sand burns my feet. The water whispers.

I stare at the old, crushed cars all lined up against the opposite bank, their front ends underwater.

“That was a drive-in theatre,” my towheaded, freckle-nosed brother tells me, again. “And one day the bank collapsed and they all fell in the river and died.”

Maybe I believe him, maybe I don’t, but I do wonder what movie they were watching when it happened. Upstream from the Sandbar, around the next corner, an ancient-looking rowboat sits half buried on the gravelly shore. Sometimes we try to get it out so we can float down the river on it, but it won’t budge. An ancient boxelder tree grows at the edge of the sand, its canopy so dense and low that we can crawl under there and sleep and stay dry even in a downpour.

Just downstream from the Sandbar, polished and crooked cottonwood branches jut out from the murky deep green swirling water. Suckers and carp and brown trout so big you don’t want to catch them lurk down there. The lost souls, the animas perdidas of the river’s name, linger there, too. And if you venture in, my grandmother says, the undertow will pull you down into the cold, deep, and dark, and you will join them. Sometimes, my brother coaxes me into wandering over to that place, and to stand close enough to the edge to peer into the depths. Look hard enough, he says, and you’ll see a big brown trout coming up for a meal. But when I dare to look in there, I see only darkness and my reflection gazing back, both curious and scared.

TEN MILES DOWNSTREAM AND 210 YEARS EARLIER, Spanish explorer Juan Maria Antonio de Rivera stood on the banks of the river and gave the river its soulful name.

Rivera had headed out from the Pueblo of Santa Rosa de Abiquiu, in the New Mexico province of Spain, in June 1765 at the order of the governor. Abiquiu, some fifty miles from Santa Fe, was the northwest outpost of the Spanish empire. Though the conquistadors and missionaries had invaded this land 167 years earlier, very few of the colonists had dared venture beyond Abiquiu, in part because the Crown forbid it. The extensive San Juan mountain range, along with the rugged valleys, mesas, and basins that spread out from it, was the domain of the Weenuchiu, Tabeguache, Caputa, and Mouache bands of Ute, and Spain didn’t want to provoke them any more than necessary. It had made that mistake before: In 1637, Spanish conquistadors took eighty Utes as slaves, then suffered a barrage of brutal retaliatory raids (and got their horses stolen, which were then used against them). And in 1680 more than a dozen Pueblo tribes up and down the Rio Grande and stretching west all the way to Hopi in Arizona revolted, killed at least four hundred Spaniards, and drove the colonists back to El Paso, where they stayed for more than a decade before returning, somewhat humbled. The best way to keep a shaky peace was to keep Spaniards out of Ute territory; if Utes wanted to trade with the colonists, they could come to Abiquiu to do so.

On one such occasion, a Ute, whose name has been lost to time, reputedly paid an Abiquiu blacksmith for his services with an ingot of silver that came from somewhere in the San Juan country. It gave the New Mexico governor a pretense—find the source of the precious metal—to send Rivera into the forbidden territory. This first official European expedition into the San Juan River watershed was really more of an undercover conquistador mission to scout the region for possible future colonization, and to confirm the existence of the mythical Rio Tizon, now known as the Colorado River.

Rivera never found the source of the silver ingot. He thought he reached the Colorado River near what is now Moab, but recent scrutiny of Rivera’s diaries by historian Steven Baker reveals that the explorer actually stood on the bank of the Gunnison River near present-day Delta, Colorado.3 Utes, suspicious of his motives, led him astray. Still, he earned a reputation as a blazer of trails and namer of places throughout the terra incognita of the Four Corners country. Eleven years after Rivera’s journey, Franciscan priests Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante would follow Rivera’s approximate route, as would a host of Spanish and then Mexican travelers over the next century.

In fact, Rivera merely followed well-established routes through a land that had been inhabited for millennia, and that had been intimately mapped in the collective consciousness of oral histories. Rivera probably wasn’t even the first Spaniard to tread these paths; mavericks defied the travel and trade ban to acquire deerskins or to try their luck in the mineralized slopes of the high San Juan Mountains, or Sierra de la Grulla—Mountains of the Crane. The Spanish mavericks, in turn, were merely following paths already well trodden by Utes, Diné, Pueblos, and nomadic hunters long before that. Almost all of the country that Rivera traveled through was not just the homeland, present and past, to a number of tribes. It was also holy land.

After leaving the Chama River, as he headed toward the Continental Divide, Rivera passed by the deep-green lake from which the people of Jemez Pueblo emerged into the Fourth World.4 He passed under the shadow of Piedra Parada, now known as Chimney Rock, an ancient lunar observatory, and he forded the chilly Pine River a dozen miles upstream of Tó Aheedlí, the residence of the Diné Hero Twins and the heart of Dinetah, the Diné ancestral homeland.

On July 4, with Utes guiding them, the explorers crossed el Rio Florido and followed a path through sagebrush, piñon, juniper, and ponderosas to the valley south of present-day Durango. Here, near a Ute encampment, Rivera stood on the steep and cobbled bank of the river the Utes called Sagwavanukwiti, or Blue River. As the Spaniard pondered the swift, cold current swirling around the boulders as big as bulls that the glaciers had pushed down from the high country so many years before, he decided to give it his own name: Rio de las Animas, or River of Souls. Contrary to current legend, the souls in the river were not perdidas, or lost, though some historians believe that it was originally implied. That adjective wouldn’t be tacked on to the name for another century or so, for reasons unknown, but it has stuck—along with an apocryphal but false origin story.

Rivera’s journals are infamously terse, and he doesn’t explain to whose souls he referred. Maybe his Ute guides had told him stories about people drowning in the river or its propensity to flood cataclysmically. He may have thought that the river had a lot of spirit, or soul. More likely, he sensed the presence of the many that had treaded this ground for centuries before he arrived.

Rivera and his men had to go several miles downstream before they could find a place to safely ford the Animas River, and still the water was up to the horses’ bellies. The Spanish explorer then made his way back upstream and climbed up into Ridges Basin, a gentle valley that runs from east to west between Smelter Mountain, Durango’s southern backdrop, and the Hogback Monocline, one of the region’s most geologically distinctive landforms. Here, Rivera encountered the remnants of a large pueblo atop a hill in the middle of the basin.5

This was most likely what archaeologists today refer to as Sacred Ridge, a small village within the larger Pueblo community of Ridges Basin, a sort of eighth-century boomtown that rose up quickly, flourished for a relatively brief period, and then—after a horrific incidence of violence—was left empty, despite the local abundance of resources.

TEN THOUSAND YEARS BEFORE RIVERA WANDERED THROUGH HERE, when the scars were still fresh from the last wave of glaciers pushing aside mountains like battleships, nomads known as Paleoindians roamed these valleys and mesas, chasing down wooly mammoth and other megafauna. They were followed by Archaic people, who most likely camped in and around the Animas Valley in the summers, subsisting on game and wild nuts, plants, and berries.

Yet it wasn’t until about the time a prophet named Jesus was born in another Holy Land on the other side of the globe that people started settling down permanently in the Durango area and farming the fertile soil. These ancestors of today’s Hopi, Zuni, and Rio Grande Pueblo people built and lived in dwellings scattered around on the mesas of current-day Durango, in Ridges Basin, and at Talus Village and the Dark-mold site on the red-dirt hillside above where my grandparents would one day set up their Animas Valley farm. They also lived in rock shelters that they constructed under a vast, overhanging layer of sandstone in Falls Creek, just west of the Animas Valley.

The Basketmaker II, as these people are known in archaeological parlance, lived here for five hundred years or more. They grew corn and squash, but not beans; they used their atlatls to hunt deer and rabbits for protein. They ate wild plants, such as amaranth. They wove baskets, sandals, and other items, but did not have pottery.

During the fifth century temperatures cooled, and farming at these relatively high altitudes must have gotten even tougher. People began bailing on the Animas Valley, and by the sixth century AD, the population of the area had shrunk almost to zero. It may have been the first natural resource bust to hit this terminally boom-bust region. Or perhaps the people who lived here just decided it was time to move on, to let this particular place rest for a while and recover from a half-millennium of human occupation.

If you want to understand Place, with a capital P, in the Four Corners country, it makes sense to begin with the Pueblo people. They’ve been in this region for thousands of years, interacting with the landscape, adapting to vagaries of climate, creating cultures and religions, developing languages. They’ve moved around, but have never abandoned, or been displaced from, their ancestral homeland. Their cultures continue to flourish in the Place from which they emerged.

During the summer of 2016, in hopes of getting a better understanding of the Pueblo sense of Place, I embarked on a trip around the Four Corners, visiting Hovenweep, Cedar Mesa, Chaco, Tsegi Canyon. On Pueblo Revolt Day, the 336th anniversary of the uprising against the Spanish colonizers, I drove my tiny 1989 Nissan Sentra across the high northern Arizona desert from Tuba City to Hopi’s Second Mesa. There, I sat down with Leigh Kuwanwisiwma in the living room of his small home.

Kuwanwisiwma has been the Hopi tribe’s cultural preservation officer for nearly three decades. When an oil company wants to drill public lands that overlap Pueblo ancestral lands, Kuwanwisiwma is called in during the “consultation” process. He fought to get Hopi ritual objects back from a Paris auction house. And he continues to search for leads on the theft, years ago, of a crucial ceremonial altar—he thinks maybe it’s serving as a headboard for some Aspen millionaire’s bed.

We talked about growing corn and about his tribe’s connections to the lands farther north. He let me taste salt he had gathered from deposits down near where the turquoise-hued waters of the Little Colorado merge with the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, and also gave me a sample of chili pepper he had grown on a dryland field nearby.

He told me that when his ancestors emerged from the Third World into the Fourth World, the holy people instructed them to “place their footprints” across the region’s landscape. Each clan was sent on its own multi-generational migratory path—the Parrot, Badger, and Greasewood clans settled at Mesa Verde, he said, and the Rattlesnake, Fire, and Coyote clans at Kawestima in Tsegi Canyon. All paths ultimately converged on the northern Arizona mesas, reaching like fingers off of Black Mesa, where the clans reside today. The other pueblos have similar migration narratives, with common themes of movement, rest, and renewal.6 After emerging from the “Sandy Place Lake,” in the mountains north of their current homeland, the Tewa people were directed to take twelve “steps” in each direction, live in each place until it is time to move on, and finally settle for good along the Rio Grande in New Mexico, writes Alfonso Ortiz, a renowned anthropologist from Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo).7

A footprint was placed in the Durango area in Basketmaker times, then another beginning right around the turn of the eighth century, during the early part of the Pueblo I period. Humanity trickled in at first, a few families making their way to Ridges Basin or, about a mile away, Blue Mesa. Word that this was a desirable place must have gotten out, because right around 750 AD, the migratory trickle turned into a human flash flood, and by the turn of the ninth century 200 people lived in Ridges Basin and another 250 at Blue Mesa. Considered on their own, each complex would have been the largest community of its time in the Four Corners region; taken together they blew every other Pueblo I settlement away.8

THE SMELL OF CIGARETTE SMOKE, OF THE PAGES OF OLD BOOKS, OF SAGE. They mingle together in my memories of my father, of his tiny home in Cortez, Colorado, of the beaten-down old cars he drove. He was a writer, a journalist, an intellectual jack of all trades. But for the last couple decades of his life—he died in 1998—his focus was on archaeology, on the Pueblo culture, past and present.

My father was particularly interested in something called AWUF, or architecture with unknown function, such as big earthen berms that arced around prehistoric structures or alignments of huge boulders with no apparent utility. The most famous AWUF of the Southwest are the Chacoan “roads,” which are not roads nor are they exclusively connected to the pueblos at Chaco Culture National Historical Park in northern New Mexico. The Great North Road stretches at least thirty-five miles directly north from the rim of Chaco Canyon out across the plateau toward the San Juan River. This was no ordinary foot path, beaten into the earth by repeated use. It was deliberately constructed to a degree that segments are still clearly visible more than one thousand years later. Rather than ebbing and flowing with the contours of the land, or veering around canyons and buttes, as a path would, it never deviates from a nearly straight, northward course. No one knows its purpose.

When I was in my late teens and early twenties I’d accompany my father on his journeys. We’d get up early, drink some instant coffee, and drive west from Cortez on some washboarded road that rattled dashboard screws free and caused dust to rise like smoke from the car’s floorboards. We ambled through sage, piñon, and juniper to the site, typically a structure from the Pueblo III period, which usually revealed itself as no more than a pile of hewn stones covered with lichen. In the heat of summer, cicadas screeched in the trees. In the winter, the silence was overlain by the distant hum of infrastructure sucking carbon dioxide from the McElmo Dome. As jays and magpies eyed us curiously we’d walk in circles or a rough grid-like pattern until we found the AWUF. It’s subtle but, to the practiced eye, unmistakable.

For most of my life I’ve been surrounded by archaeology and archaeologists—my brother’s one, my stepfather was an archaeologist working around the West for the federal government for decades, and my mom wanted to study archaeology in college but was shot down because she was a woman. As a young man, though, the field left me cold (an ailment of which I’ve since been cured). I couldn’t see how excavating the tangible remains of material culture could ever get at the juiciness of what life was really like—what people felt, thought, how they interacted, and what philosophical or religious forces motivated them. Nor could it answer the question that always gnawed at me: Why here? Why did they choose this place, despite the hardships, to build a civilization? Sure, there were concrete, practical reasons: Ridges Basin is a gentle valley with a southward-slanting slope on one side, a stream, and even a marsh, where tasty waterfowl often alighted. But bigger factors must have been in play. Just consider Chaco’s elaborate pueblos, which rose up in a landscape so austere that the early builders had to drag unwieldy ponderosa pine trees from the Zuni Mountains and Chuska Mountains, each fifty miles distant, for architectural uses, and may have even imported corn. It was a pragmatist’s nightmare on par with modern-day Las Vegas.

“Here, the human landscape is meaningless outside the natural context—human constructions are not considered out of their relationship to the hills, valleys, and mountains,” Rina Swentzell, a Santa Clara Pueblo scholar and an architect, wrote with my father and two archaeologists, Mark Varien and Susan Kenzle, in a 1997 paper. “Puebloan constructions are significant parts of a highly symbolic world. Even today, that defined ‘world’ is bounded by the far mountains and includes the hills, valleys, lakes, and springs.” That suggests that places like Chaco, and Ridges Basin, became communities or political centers not only due to tangible factors, but also because of where they fit into the symbolic world. Perhaps the “roads” and other AWUF were bridges of sorts, linking the built architecture with the symbolic world, a sort of architectural map of the Pueblo cosmos.

The Great North Road, for instance, points toward 14,252-foot Mt. Wilson, the highest peak in this part of the San Juan Mountains. If one were to follow the road’s trajectory—or what archaeologist Stephen Lekson calls the Chaco Meridian—toward Mt. Wilson, she would first pass through the Aztec Great House on the banks of the Animas River and then, right where the meridian transects the Hogback Monocline, Ridges Basin.9 The monocline is not only dramatic looking, but its coal outcrop has been known to ooze methane, spontaneously combust, and even “erupt,” particularly where waterways slice through the monocline. Surely the ancients witnessed these phenomena. We can only guess as to whether it influenced their decision to settle nearby, or the tragedy that followed.

ON A LATE SUMMER’S DAY IN 800 AD, the Ridges Basin community probably would have looked something like this: The monsoon and its late afternoon downpours have greened up the grass, punctuating it with chaotic wild sunflowers. People mill about their hamlets tending to penned-up turkeys, grinding corn, making pottery. On the outer edges of the community, emerald shocks of corn sway with the breeze alongside beans and squash, planted in alluvial fans.

There is a small stream but there are no dams, no diversion structures, no irrigation ditches leading to the fields. These were dryland farmers. Across the ancient Pueblo world, with the possible exception of the Tewa Basin along the Rio Grande, acres and acres of corn and beans and squash grew without any liquid nourishment aside from rainfall; the same is true at Hopi today.10

This practice can befuddle the modern Westerner. Euro-American settlers in the West are defined by the propensity to move water from stream to field. It wasn’t that the Pueblos lacked the technological know-how to divert streams onto their fields; they did capture, store, and divert rainwater and arroyos, after all. They appear to have chosen to put themselves at the mercy of the rains rather than try to wrest control over temperamental waters that rushed down from the mountains. They were attuned to the seasons and the vagaries of the weather. They prayed for winter snow and summer rain; they danced to summon the sun and to beckon the land to bloom and bear fruit. When that failed, they adapted accordingly, sometimes even moving, giving the land a chance to rest. The place shapes them, not the other way around. “We’re a corn culture,” Kuwanwisiwma told me. “The environment can force you to be humble.”

It’s especially ironic, then, that the remains of those same corn fields at Ridges Basin are now inundated by a reservoir, Lake Nighthorse, the end product of an anything-but-humble, decades-old dream to plumb the watershed, to lift up a portion of the Animas River and send it over the ridge to the La Plata River, where arable land is plentiful but water scarce. The plan for the Animas-La Plata Project, which initially included several reservoirs, a coal power plant on the Southern Ute reservation, and hundreds of miles of canals, pipes, and tunnels, was diminished over the years, finally ending up being no more than one pumping plant lifting Animas River water hundreds of feet uphill into Ridges Basin, where it currently sits, stagnant, in order to fulfill Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute water rights. Someday the water will be piped to distant fields, or to another power plant, or even to a golf course in the desert.

In advance of the reservoir’s creation, archaeologists were sent in to catalog what forever would be entombed by Lake Nighthorse. The most intriguing, and disturbing, finds were made at a village the archaeologists called Sacred Ridge. Atop this knoll sat a little hamlet made up of several structures. Another dozen pit structures, with associated surface dwellings, were situated on the knoll’s slopes, oriented toward the top of the knoll like people sitting around a fire. The pit structures tended to be larger than those found elsewhere in the region during this time, and some were surrounded by “stockades” or fences of a sort—possibly an early form of AWUF. The entire knoll-top hamlet was similarly fenced in, and its pit structures seem to have been used not just for living in, but also for community ceremonies. Perhaps most notable was the tower, made of wood and adobe in the jacal style, on top of the knoll. Though masonry towers would become commonplace at pueblos hundreds of years later, this appears to be the only one from this particular time period.11 Its function is also unknown.

Archaeologists who excavated the sites in Ridges Basin theorize that the architecture and prominent location suggest that Sacred Ridge was home to the upper class, the community’s elite.

In the early 800s the clouds were offering less rain than they had a few decades earlier, and the dense population was beginning to put pressure on local resources. It was nowhere near a crisis, yet something must have gone awry. The community, the landscape, or both were somehow out of balance.

And over a short period of time, maybe even in just one day, someone came in and overpowered nearly three dozen of Sacred Ridge’s residents—men, women, children, even domestic dogs. Some of the captives were hobbled, their feet, ankles, or toes broken to keep them from running and to scare others from doing the same. Then the perpetrators tortured, scalped, and finally killed the victims, butchered the corpses, tossed the thousands of pieces into the Sacred Ridge pit structures, and then lit the structures on fire.

The dehumanizing stereotype of the Pueblo people as “peaceful farmers” was long ago debunked. Archaeological evidence and oral history reveal that violence, whether it was one-on-one murders, mass killings, or warfare between different tribes or groups, was not unheard of in prehistoric or historic times. Like every other society throughout history, these ones had their moments of darkness. Yet evidence suggests Sacred Ridge was among the most brutal, particularly for that time period. Archaeologists have a handful of hypotheses. It appears as if neighbors massacred neighbors. Maybe it was ethnic cleansing, a populist revolt, or a reaction to suspected witchcraft.

Soon thereafter, everyone in the Durango area up and left. By 820, the place was devoid of humanity. “What is intriguing about the abandonment of the Durango area is the suddenness and totality of the exodus,” writes archaeologist James M. Potter. “Even with a climatic downturn and depleted local environment, the Durango area could have continued to support a smaller population.”12

Over the following centuries, the Chaco region bloomed and the population ballooned. When that society waned, new ones grew up along the Animas River near present-day Aztec, New Mexico, in the Mesa Verde region, and in southeastern Utah. Yet no Pueblo people ever came back to the Durango area to live, despite the reliable water sources, fertile soils, and abundance of low, farmable mesas. The trauma from the Sacred Ridge massacre not only must have rippled throughout the Animas River valley, but also reached down through the generations, leaving a dark pall over this place, its spot on the symbolic map forever tainted.

THE PUEBLO PEOPLE TENDED TO GENTLY PULL UP THE ROOTS AND MOVE in response to broad climatic shifts. The Utes, who probably arrived in the Four Corners country from the West at the tail-end of the Puebloan era, moved with the seasons. They were nimble, light on the land, mindful of subtle shifts in flora and fauna. If the Pueblo people’s calendar was marked by a shaft of sunlight touching the center of a spiral carved in stone, the Utes’ was imprinted by the first bear emerging from hibernation or bucks shedding their antlers or the skunk cabbage’s hue transforming from green to rust.

After the Animas River swelled up with snowmelt, the Weenuchiu band followed well-worn trails up the river and into the high country, following the deer, collecting osha, feasting on tart wild raspberries and tiny, sweet alpine strawberries. When the aspen leaves turned yellow and they’d awake to lace-like frost clinging to the grass, they’d pack up and head back down to the lowlands, gather into larger groups, and stay in one place for the winter. They followed the annual cycle in the San Juan Mountains and the surrounding lowlands for three centuries before the Spanish arrived in 1598. Even then, the Ute people were mostly left alone; when in the early 1600s an escaping band of Ute captives managed to get away with some Spanish horses, they became even more formidable warriors and hunters.

When Rivera arrived at what he called the Animas River, he encountered a Ute rancheria, or encampment. He plied the people there with tobacco, corn, and pinole, in hopes of finding a man named Cuero de Lobo, who purportedly knew the source of the silver. Instead, Rivera was sent on a goose chase of sorts; while the Utes were willing to help Rivera find his way, they seem to have suspected his motives, and purposefully sent him astray more than once. When he finally found Cuero de Lobo, Rivera was led to a “mountain of metal” in the range west of Durango. Rivera referred to this branch of the San Juans as Sierra de la Plata, because he thought it was where the silver had come from. Again, he was disappointed; the samples taken from the mountain didn’t have much in the way of precious metals. While Spanish and then Mexican travelers would continue to come into the Animas River country, they only passed through, oblivious of the mineral bounty hidden away in the nearby mountains and, most likely, their ceremonial significance, as well.

“In the north, First Man placed the Dark Mountain (Dibé Ntsaa),” writes Diné, or Navajo, historian Clyde Benally. “He planted it with a Rainbow and covered it with Darkness, Dark Mist, Female Rain, and Blue Water. He sent Darkness Boy and Girl there, to what is known now as Hesperus Peak in the La Plata Mountains of Colorado.” And so, the northern boundary of Diné cosmology, one of its most sacred places, was established. Diné oral history refers to the builders at Chaco, which would have meant the Diné were in the Four Corners country as early as the 900s. Archaeologists generally believe, however, that the Diné came much later—in the 1400s or 1500s—from the North, crossing through the San Juan Mountains into the lowlands along what would become their sacred river of the North, Bits’íís Doo ninít’i’í, or the San Juan River, and beyond. They lived, farmed, and hunted in the lower Animas River watershed, and Totah, where the Animas and La Plata rivers join the San Juan, is a significant region. To this day they continue to make pilgrimages to their sacred mountain of the North.

When Rivera stood on the steep banks of the river, he was undoubtedly oblivious to the thousands of years of indigenous history that had already unfolded there. He didn’t know the Diné name for the Animas River, Kinteeldéé’ ´Nlíní, or “Which Flows from the Wide Ruin.” And he must not have cared about the Ute name, or any of the many names before. Maybe on some intuitive level, though, he felt that presence in the water, the trees, the mountains, and that is why he said the river was full of souls.