Читать книгу River of Lost Souls - Jonathan P. Thompson - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

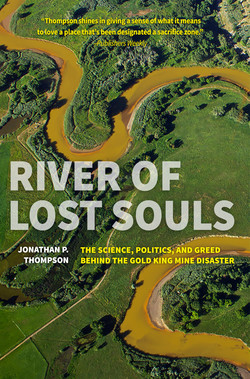

ОглавлениеOlaf and the Gold King

IT’S APRIL 1891 AND OLAF ARVID NELSON IS DYING. He lies in his bed in the little house in Howardsville, a few miles upriver from Silverton. When he tries to stand he’s gently pushed back to the pillow by Louisa, his wife. His lungs are filling up with fluid, his body drowning itself. Whenever he moves, or breathes too deeply, it feels and sounds as if nutshells are rattling around in his lungs.

“The Mighty Swede” does not complain. Even before he was sick he didn’t talk much. Words don’t have much to them. They flitter away forgotten as soon as they leave your lips. Work is everything. And damn did he ever work. Six days a week drilling, blasting, and hauling ore out of the Philadelphia Mine, which he leased. And nights and Sundays up at his own claim on Bonita Peak.

NELSON FIRST EMERGED INTO THE HISTORICAL RECORD, and was nearly wiped right off of it, as a twenty-two-year-old wannabe miner in search of opportunity.15 During the winter of 1878–79, he and fellow Swede Jonathan Peterson headed up Cement Creek on the brand new wagon road to the nascent camp of Gladstone. From there they continued up the canyon to Brown Mountain, where they set up a prospecting camp in a rickety cabin dug into the south-facing slope. During a normal winter, the mountainside would be covered with several feet of snow, but it had been unusually warm and dry, making life easier for the miners. One February evening, after a long day of digging, the miners retired to their hut, kicked off their soggy boots, and settled in for the night. Meanwhile, the mountain slope was doing some settling of its own as melting snow oozed into the earth, softening and lubricating things. Soon, a chunk of the slope broke free, and a torrent of rocks, dirt, and ice rained down on the cabin, crushing it.

Both men survived the calamity, though both were pinned under debris, with no one nearby to come to their rescue. Peterson was able to free himself, then went to work on Nelson, who was more thoroughly stuck. He had little more to work with than his hands, a straight razor, and his stubbornness. Eleven hours later, Nelson, too, was free and virtually unscathed. The two walked down Cement Creek, barefoot, to Gladstone and caught a ride back to Silverton.

The February warmth that had loosened the earth and nearly taken Nelson’s life continued into the spring. Today that sort of climatic anomaly would be considered a threatening drought; the newspapers at the time hailed the mild weather as yet another reason to put down roots in the San Juan Mountains. By then, the main route in and out of Silverton via Stony Pass to the east was being replaced by the Animas Toll Road that followed the Animas River to the south, opening up the Silverton market to Animas Valley farmers and ranchers. The farmers, Julia Mead among them, put seeds in the ground in mid-March that year, two months ahead of time. By May, most of the snow had melted off of even the highest mountain passes, and the relentless high-altitude sun had turned the forests to tinder.

During the first days of June 1879, somewhere near present-day Purgatory ski resort, a spark or flame or hot ember leftover from a traveler’s campfire ignited some ponderosa pine needles on the forest floor. The flames jumped to the gambel oak, then to the spruce trees, their canopies exploding into fire. The conflagration marched steadily up the Lime Creek drainage toward Silverton, charring everything in its path.

L. W. Pattison was working just south of Silverton at the Molas Mine as the flames approached, and wrote this account:

One of the most terrific fires that has ever come under my observation occurred yesterday down the Animas Trail. We had noticed the heavy columns of smoke from the South and southwest for some days but anticipated no danger until after dinner yesterday, when the air became so heavy with smoke and the flames appeared to be moving so rapidly, that we began to pay attention to the matter.

Pattison and his fellow miners buried their explosives and shored up the cabin against the flames. A big, cinnamon-colored bear barreled through the camp, followed by several deer, oblivious to the humans there. Too late to outrun the flames, the men bolted to the mine tunnel. From that place of relative safety they watched in dismay as one of their burros wandered directly into the inferno.

The Lime Creek Burn, as this “scene of unusual and weird magnificence” would become known, charred twenty-six thousand acres of high country before subsiding. It would stand as the largest fire to burn in Colorado until the mega-fires of the early 2000s blackened hundreds of thousands of acres of the state’s forests. The Burn forever altered the landscape south of Silverton. Before the blaze, the area around Molas Lake and Molas Pass was densely forested with conifers; today, it’s mostly wide open meadows studded by blackened stumps, a smattering of aspen trees, and incongruously green Scotch pines, a non-native species that was planted by the U.S. Forest Service beginning thirty years after the fire.

The flames stopped just short of Silverton, due, perhaps, to the fact that all the surrounding slopes had been clear-cut. But ash and smoke rained down on the town for days. For a few settlers, Nature’s terror had crept a little too close to home, and they pulled up stakes and moved elsewhere. Most, however, dug in their heels and stubbornly vowed to stay.

The blaze was likely caused by the unattended campfire of one of the many mountain-roaming cowboys or hunters who were out and about at the time. But a few months later, a more useful scapegoat would emerge. In September members of the White River band of Utes in northwestern Colorado rose up and killed Indian agent Nathan Meeker and his staff and kidnapped his family, an event that came to be known as the Meeker Massacre. Meeker was a racist, and one who endeavored to convert the White River band from nomadic “savages” to sedentary Christian farmers. He kept pushing the Utes, who had already been squeezed out of much of their homeland, until finally they stood up to him. Meeker called in the cavalry, leaving the Utes little choice but to fight. The isolated incident inflamed a statewide Ute-phobic rage.

“Indians are off their reservation, seeking to destroy your settlements with fire,” warned Colorado Governor Frederick Pitkin, who had enriched himself with San Juan Mountain mine investments. “The Utes must go!” Someone should have reminded Pitkin that the Brunot Agreement explicitly gave the Utes free rein to roam, hunt, and forage “off the reservation” in the San Juan Mountains; to take that freedom away was equivalent to robbing them of their identity. Silvertonians took up arms and prepared for a fight. My ancestors, in the Animas Valley, joined with others at a hastily constructed sod fort on the north end of the valley. Extremists ached for a provocation, so they could settle the “Ute Question” once and for all. “Here in Silverton we have received 40 stand of arms and have perfected a military organization,” noted the Miner newspaper, describing a sort of nineteenth century version of today’s right-wing “militias.” “We say bring on your Utes—the Johns and Joes can soon exterminate them.”

The attack never came, however, leaving the settlers and their representatives in Denver and Washington to resort to more subtle forms of extermination—like labeling the Native Americans as terrorists. The Lime Creek Burn was retroactively attributed to the Utes. A La Plata County resolution forwarded in 1880—a year after the blaze had gone out—claimed that the Utes set the fire to roust game or “to maliciously injure the settlers and miners . . . destroying millions of dollars worth of timber and a vast amount of private property.”

For the next twenty years, every skirmish that involved one of the “Rabid Reds” was framed by newspaper accounts and politicians as a precursor to the next Indian War. Every Ute was deemed a potential terrorist, aching to launch another Meeker Massacre, regardless of the fact that the southern bands, under the leadership of diplomatic peacekeeper Chief Ouray, put up little resistance to the encroachment on their homeland. The persecution was part plain-old racism, and fear of the “other.” Mostly, though, it was a calculated campaign designed to give the white newcomers more land and resources. By 1880, the game populations were already dwindling, thanks to over-hunting by the newcomers, and the Utes competed ably for that scarce resource. In the lowlands, the farmers and ranchers were outgrowing the land that had been stolen on their behalf in earlier treaties, and they wanted more. Meanwhile, the people who had established businesses in Durango had saturated the market. They needed more customers, and a new land rush for Ute reservation lands was just the ticket.

Portraying the Utes as a threat provided a justification for the feds to push them further and further into the margins in the hope that they just might go away. Meanwhile, whites who were truly violent and threatening were allowed, quite literally, to get away with murder, so long as some of their violence was directed toward the Utes.

A LATE SUMMER CHILL SETTLED OVER THE YOUNG TOWN OF SILVERTON as the sun fell behind Anvil Mountain on the evening of August 24, 1881. The light faded, and the saloons—the Tivoli, the Senate, the Blue Front, the Golden Star, the Rosebud, the Star of the West—filled up with miners, merchants, and travelers. It was a rowdy night. Every night was a rowdy night in Silverton.

The crews building grade and laying tracks for the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad had yet to make it into Baker’s Park, but by now their arrival was imminent, and in anticipation the little smattering of houses Rhoda had witnessed had blossomed into a bona fide town with stately residences and a lively commercial district, replete with two bakeries, a furniture-making and undertaker business, and two shoemakers. A man could get his dingy clothes cleaned at the Quong Wah or Sing Lee laundry, stop in at the Tennyson Bath House, and get shorn next door at the Merrifield Barber Shop. The San Juan Herald had emerged that summer to compete with the Miner, making Silverton a two-rag town. Law offices nearly outnumbered saloons. There was just one church.

Olaf Nelson had not been scared away by his brush with death, nor by Silverton’s close call with wildfire. He was here to stay, along with hundreds of others like him, folks from Italy, Austria, Wales, Poland, and China, looking to reinvent themselves on the rugged but quickly civilizing frontier. A few months earlier, Nelson’s wife Louisa had given birth to their first child, Anna. Nelson worked hard but played little, his Lutheran upbringing keeping him above the bawdy fray.

That night, in a sleeping room in the back of the Senate Saloon on 13th and Greene (in the now-vacant lot north of the Teller House), Town Marshal David Clayton Ogsbury was trying to do the same. He was dead-tired, but unable to sleep.16

Ogsbury, born in New York, had come to the San Juans in the early 1870s. He had been a saloon owner, prospector, bridge designer, and store clerk. But his real calling was law enforcement, and as Silverton’s marshal he was one of the area’s most respected lawmen. On nights like this, however, he would just as soon be prospecting.

Young Silverton was boisterous, but some semblance of law and order tended to keep the stew from boiling over into bloodshed. The same could not be said for Silverton’s junior, downstream neighbors, Durango and Farmington. Ogsbury’s colleagues in the lower Animas River country had been dealing with cattle rustling, highway robbery, and theft, much of it perpetuated by two warring gangs, the Farmington-based Coe-Hambletts and the Stockton-Eskridge gang, led by Ike and Port Stockton, cattlemen who had come up from Texas, and Harg Eskridge, who owned a Durango saloon.

In late 1880 the simmering tension between the two gangs boiled over into outright war when a Coe ally was killed and, in retaliation, the Coe-Hamblett boys shot and killed Port Stockton. The Stockton-Eskridge faction retreated to Durango, the Coe-Hambletts pursued them, and in April of 1881 the two gangs clashed in an intense firefight on the edge of town. A stray bullet made its way into the office of the Durango Record, the young town’s first newspaper, where it just missed hitting publisher, editor, reporter, and writer Caroline Westcott Romney. Romney, a forty-year-old seasoned journalist, came to Durango from Chicago via Leadville the previous year, and printed the first issue of the Record on a “job press” in a canvas tent on a frigid, snowy December 29, 1880. Romney wasn’t one to be cowed by gangs of rustlers or anyone else: During her three-year tenure in Durango she was a champion for women’s rights, rallied against prostitution, and held a special disdain for opium dens and their patrons. And as soon as the dust from the firefight had settled, she stood up to the Stockton-Eskridge gang and demanded they be run out of town.17 And they were, sort of. Town leaders asked the bunch to leave, and even paid them $700 as an incentive, which was enough to get them to skedaddle, for a while.

But a couple months later, the Stockton-Eskridge boys were instrumental in chasing down and killing “bands of renegade Indians” who had allegedly killed three ranchers near Gateway, Colorado. Ute-phobia festered at a fever pitch among the white newcomers, and they not only forgave the gang of recidivists and murderers for their past deeds, but elevated them to the status of Indian-fighting heroes. Even Romney, who thought the scant amount of land left to the Mouache, Caputa, and Weenuchiu bands would be more productive in white hands, was swayed, becoming one of the gang’s most vocal defenders. When the criminals moseyed back into town, lawmen like La Plata County Sheriff Luke Hunter turned a blind eye, allowing them to continue their lawless ways.

On that late-August afternoon, gang members Bert Wilkinson, Kid Thomas, and Harg Eskridge’s brother Dyson went on a robbing rampage on the Animas Toll Road, and were rumored to be headed toward Silverton. Ogsbury waited anxiously, though there was little he could do once they arrived, since he had yet to receive a warrant from La Plata County.

Typically, Ogsbury had to grapple with slightly more benign crimes. Two days earlier, for example, he had tossed Bronco Lou—the barkeep at the Diamond Saloon—into jail for enticing a man into her bar then robbing him blind. Bronco Lou (aka Susan Warfield, Susan Raper, Susan Stone, Bronco Sue, Lou Lockhard, and Susan Dawson) was one of the more colorful characters of the time, and had she been a man would surely have gone down in history as one of the West’s outlaw folk heroes along with Jesse James and Billy the Kid. Instead, she was maligned as a “prostitute and thief.” Lou was no prostitute. She was a skilled larcenist, but also so much more. Bronco Lou could outshoot and outride just about anyone in the region and was “fierce as a fiend in her ferocity or as gentle as a lamb or as soft as an angel in her devotion to those she liked.”18 When she and a group of her cohorts got tangled up with a southern Colorado posse, Lou not only nursed the outlaws back to health while they were in jail, but then planned and carried out their escape. When they were recaptured, and about to be hanged, Lou again rescued the men. She allegedly killed two husbands prior to her arrival in Silverton, and singlehandedly saved a third husband’s life from an Indian attack (he left her shortly thereafter). On that August night, Lou would be the least of Ogsbury’s troubles.

At about eleven p.m., Ogsbury was roused from sleep by a knock.

“Clayt, wake up,” said a familiar voice. Ogsbury opened his eyes and saw Charlie Hodges, a local businessman. He was accompanied by Luke Hunter, sheriff of La Plata County, who had finally arrived with the warrants. Ogsbury quickly got dressed, fighting the temptation to ask Hunter what in the hell had taken him so long. He suspected Hunter of going easy on the Stockton gang. As far as Ogsbury was concerned, they should have all been behind bars already.

Little did Ogsbury know that Hunter, after arriving in Silverton, had taken his time finding the marshal, and in the meantime had indirectly warned the outlaws that the local law was on to them. “We’ll need help,” said Ogsbury. “I’ll send for Thorniley [San Juan County Sheriff George Thorniley], and we can round up a few others, just in case there is trouble.”

“That won’t be necessary,” replied Hunter. “I know these men. They’ll give in peacefully.”

So the three of them, Ogsbury, Hodges, and Hunter, set off toward the Diamond Saloon, aka Lower Dance Hall, Silverton’s rowdiest drinking establishment.

As they drew near, they saw the silhouette of a man in the street and stopped. Ogsbury instinctively reached down and lightly touched the handle of his pistol. He peered into the darkness in an attempt to identify the still, silent figure.

A flash of light, a crack in the night, and then a sickening thud as Ogsbury’s body hit the dusty street.

The shooter was one Bert Wilkinson, a tall, skinny, freckle-faced nineteen-year-old from a prestigious family, who had taken up with a rough crew. He and his companions took advantage of the chaos that ensued. Wilkinson and Eskridge headed for the hills, while Kid Thomas, an African American, tried to hide out in town. It didn’t work and Thomas, “The Copper Colored Kid,” was captured and tossed in the small town jail. The next day, a mob of vigilantes broke him out and hanged him in the streets of Silverton.

Thomas’s companions, meanwhile, managed to head up Mineral Creek, over into the San Miguel River drainage, and then into the Dolores, before crossing back to the east, ending up at the home of Ellen Louise Wilkinson, Bert’s mother, just south of where Purgatory Ski Resort sits now. Ellen Louise sent her son and his companion several miles east, to a less-traveled place on Missionary Ridge. A couple of days later, she summoned gang leader Ike Stockton, and asked him to go help her son escape to Mexico. Stockton ambled into the fugitives’ camp, sent Eskridge away, then marched Wilkinson right into the hands of the law, betraying his young protégé for the $2,500 reward on his head.

Wilkinson was tossed into the Silverton jail, and less than a week later vigilante justice reared its ugly head once again. A mob broke into the jail, ordered the guard to leave, and put a noose around Wilkinson’s neck.

“Do you have any last words?” a voice asked from the crowd.

“Nothing, gentlemen. Adios,” replied Wilkinson, and he kicked the chair out from beneath himself.

Such are the violent pangs felt by a frontier community, awash with wealth from the mines, in its adolescence. Contrary to how today’s peddlers of the wild, wild west, with their fake gunfights, might portray the history of Silverton and Durango, the reality is, this sort of lawless, highway-robbing, gun-slinging, and frontier justice were a mere blip on the region’s record.

The murder of Marshal Ogsbury and the lynchings that followed were not just the climax of this short period in history, but also the dying gasp. In Silverton, the Diamond Saloon was shut down and demolished and Bronco Lou run out of town. Ike Stockton was gunned down in the streets of Durango, not because he was an outlaw, but because he betrayed his young friend. Stockton’s gang disintegrated and the Coe-Stockton feud evaporated. Communities moved to end the lawlessness, and even implemented gun control statutes that are far stricter than today’s. “Firearms in the daily walks of life have no place in our modern civilization and should not be carried,” noted a Durango mayor in 1903. The communities of the San Juan country, though still brand new, were maturing.

ELEVEN MONTHS AFTER THE SILVERTON SHOOTING, a far more cataclysmic sound than a gunshot would echo through Baker’s Park: the whistle of the first steam locomotive. The railroad had finally arrived, marking a huge pivot in the region’s history.

Prior to that fateful day in July 1882, mail and supplies were brought into Baker’s Park by horse, mule, or wagon on rugged trails over high mountains. Throughout the 1870s, the most traveled route to the outside world was a seventy-mile journey to Del Norte, in the San Luis Valley. The trail crossed the Continental Divide at Cunningham Pass, elevation 12,090 feet (currently part of the Hardrock Hundred ultramarathon course). During the winter, which at these elevations can last six months or more, the horses and burros were traded for wooden skis, ranging from six to twelve feet in length, known as snowshoes.

Heroic and hardy mail carriers—mostly Nelson’s fellow Scandinavians—plied the long boards, usually tag-teaming the route and braving avalanches, frostbite, hypothermia, and snow blindness to keep Silverton running through the winter. One mailman once carried sixty pounds of newsprint over the route in order to keep the local rag in print. Astoundingly, only one mail carrier perished. On November 27, 1876, John Greenell, née Greenhalgh, set out from Carr’s Cabin on the other side of the divide on the return trip to Silverton. He never arrived. A group of searchers found his body a few days later, frozen to death near the top of the pass, his hand rigidly clutching his mailbag.

The train was challenged by snow, as well, but it opened up a thick artery connecting Durango, rich with coal, timber, cattle, and crops, with the mineral-rich veins around Silverton.19 The miners got access to heavy equipment that would have been almost impossible to haul over the passes with mules, and they could then send their ore by the railcar-load back down to Durango and the new San Juan & New York smelter built along the Animas River’s banks. Potential investors in the mines no longer had to brave sphincter-puckering wagon rides over steep passes to see future prospects.

The rails stretched from Denver down to Alamosa, in the San Luis Valley, then further south to Chama, New Mexico, where they picked up the old Ute and Spanish trail to Durango before following the Animas River to Silverton. The railroad’s advent didn’t just impact the mining camps. The pair of steel ribbons and the coal-eating, smoke-belching locomotives that rode on them rapidly transformed the entire region’s landscape, cultures, and economy. The locomotives sucked up water from rivers and streams, and new coal mines were opened to feed the chugging beasts. Glades of tall, straight, and wise old ponderosas near Chama, on the Tierra Amarilla Land Grant, were sheared down en masse now that there was an easy way to haul them to market. Once-isolated villages along the old Spanish trail, settled in the 1870s by members of the New Mexican Penitente Brotherhood looking to flee religious persecution from mainstream Catholics, were suddenly linked to the outside world.

Towns and sawmills and cattle-loading chutes popped up along the tracks; subsistence farms and ranches morphed into commercial-sized operations. And in the high country, the mostly entrepreneurial mining trade slowly transformed into an industrial-scale concern, funded by outside capital. In 1881, approximately six hundred tons of ore were pulled out of Silverton-area mines. A couple of years later, it had jumped to fourteen thousand tons and climbing. The population of Silverton and surrounding towns ballooned into the thousands.

By then, Olaf Nelson had another mouth to feed, a son named Oscar. Freelance prospecting wasn’t paying off, so he got a real job up at the Sampson Mine, located on the upper slopes of Bonita Peak. It was one of the upstart mines in the area, first staked in the early 1880s. In 1883 its owner, Theodore Stahl, had a mill built in Gladstone along with a tram to link mine and mill, one of the first in the San Juans. Nelson’s job was to run the tram, which carried ore down to the mill and served as a sketchy, primitive chairlift for miners, adding to the long list of ways to die while in the trade. Nelson and his family moved into the mine’s boardinghouse, perched at twelve thousand feet above sea level near the mine portal, in 1885.

That is where Louisa, Olaf, Anna, and two-year-old Oscar found themselves on a January evening in 1886. A blizzard had raged outside since late the previous night and even during the light of day the flakes came down so thick that Olaf couldn’t see beyond the second tram tower. As they sat in the dim light of lanterns they occasionally heard a deep and eerie whoomph as slabs of snow tumbled from the roof. But inside, with a stoked stove and the deep snow providing insulation, they were warm, at least. The baby slept, Anna read, and Louisa knitted. Olaf felt another whoomph, only deeper, louder. He heard a hissing, and noticed that a stream of smoke was blowing out of the stove door. Then the crashing, the world moving, the wall rushing towards them: Avalanche.

A baby was crying. Louisa called out: “Anna. Anna.” Olaf Nelson moved silently and quickly through the darkness. Amid the wreckage he found the pipe from the stove, still hot, and used it as a shovel. He dug frantically through the snow toward the cries, tears rolling down his face.

Once again, Olaf Arvid Nelson had cheated death. Louisa, Anna, and Oscar made it out of the catastrophe with nothing worse than a few scratches, bruises, and a lot of fear. The time-line gets fuzzy here, but it seems that the family relocated down the slope to Gladstone, where Louisa operated a store while Nelson stayed on at the Sampson, now working underground.

Nelson was no geologist, but he had spent enough time poking around in these rocks to get a gut sense of how mineral-loaded veins operate, and what sorts of trajectories they tend to follow through a mountainside. Every day that he stepped into the Sampson Mine and hammered and drilled and blasted at the stope, he was also calculating. He deduced that he and his coworkers were mining in the wrong place; the vein would be richer, thicker, riper elsewhere. He kept his thoughts under wraps, though, and on April 11, 1887, he acted on his hunch, quietly staking a 1,500-foot by 300-foot lode claim on Bonita Peak’s slope, not far below the Sampson workings. He called it the Gold King.

Nelson quit the Sampson and he and the family—he now had five children—moved to Howardsville. Louisa started up another store, while Nelson leased the Philadelphia Mine, a proven producer, so that he’d have a semi-reliable source of income. It was a success; he was pulling out ore that netted two hundred dollars (equal to $5,000 today) per ton, a relatively high grade. He also was appointed constable of Howardsville in 1890, adding to his workload. But what Nelson really wanted was to build a mine from the ground up, to strike it rich on his own, and he spent all of his spare time up on Bonita Peak at the Gold King, working at night, on Sundays, in storms, and in sunshine.

This wasn’t the way mining worked anymore. You were supposed to stake a claim then go out and promote it and bring in some venture capital to finance development. That’s the kind of large-scale capitalism that had turned San Juan County into a mining powerhouse, with the industry employing more than 1,200 people at 176 mines, thirteen mills, and two electric plants. But no, that wasn’t Nelson’s way. He kept his find quiet, working surreptitiously and alone. He endured cold and rain and the dank and dusty underground air for more than three years, sometimes working all night long, ultimately sinking a fifty-foot shaft and a fifty-foot drift. Then he became so sick that he could work no more. They called it pneumonia, a common affliction of the day. It might have been silicosis, or miner’s lung, which had yet to be classified. Maybe Nelson had just worked himself into his deathbed.

Nelson’s breathing is shallow and useless. Outside, huge, lacy flakes of snow catch the soft, late-afternoon light as they fall slowly to the earth. It is April 1891 and Olaf Arvid Nelson is dying. “And for what?” He asks in a raspy voice, speaking to no one in particular. Then he says no more. His obituary will remember him as an “honest and hard working man.” It won’t even mention the Gold King Mine.