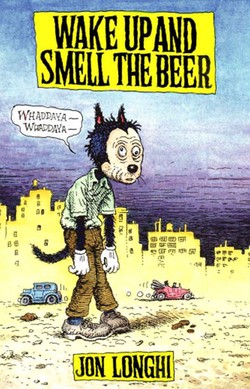

Читать книгу Wake Up and Smell The Beer - Jon Longhi - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеDada Trash could burp the alphabet. Once he got a couple beers in him, it was easy. This little talent evoked drop-jawed wonder when displayed at parties. And then, just a couple seconds after that last gastric Z, Dada Trash evoked even greater gasps of awe when he burped the alphabet backwards. I shared a house with a bunch of guys and I'm proud to say he was one of them.

Dada Trash had a tattoo of Alfred E. Newman on his stomach. You remember Alfred, the goofy-looking guy with freckles and a front tooth missing, from the cover of Mad magazine. When Dada Trash was on the beach it looked like he had Alfred peeping up out of his swim trunks. Not only that, but the tattoo was placed so that my friend's bellybutton looked like a bullet hole in the middle of Alfred's forehead. The tattoo artist even threw in a word balloon that, of course, read: “What, me worry?”

My friend proudly referred to himself as The Garbage Artist. “Trash is the only raw material that is truly limitless,” he once said, and set about building a body of work from things thrown away by others. His artistic creations were celebrations of everything useless and worthless. Of course he had done all the basics - metal sculptures out of garbage cans soldered together, collages from bottle caps and used tampons - all the exercises you'd expect from someone who'd borrowed the name of that mad art movement in the '20s. “I didn't borrow the word Dada,” my friend once told me. “I scavenged it after history threw the term away.”

Well, after my friend Trash picked the name from the landfill of time, he dusted it off and reclaimed it for himself. Legally. Back in 1984, one Joe Smith went down to City Hall, filled out some paperwork, and left the building as Dada Trash. That's the name on his driver's license and his social security card.

“When I die, all it's going to say on my tombstone is TRASH,” he once said.

In art school Dada retreaded all the classic Dada and Surrealist experiments. Automatic painting. Cut-up texts. Experimental writing. He taught himself to surrender to the whims of chance, learned to avoid the noose of habit. Dada was always looking for something different and all this gave him a special sensitivity towards refuse. Things discarded, unwanted. “There's almost as much garbage around us as there is air,” he said one night at a party. So trash became his atmosphere. Rotten banana peels and rusty tin cans were his brushes and all the world became his palette.

For his senior class project, Dada submitted a pile of garbage which he claimed was heaped in an “aesthetically harmonious” fashion. He had spent two weeks stacking and restacking the smelly refuse until he got it just right.

“What about the roaches and vermin crawling all over that mess?” his perplexed professor asked. “How do they fit in with your artistic vision?”

“Those insects are symbolic of the critics,” Dada Trash said. “They crawl all over the carcass of modern life but still can't figure out where the stink comes from.”

The teacher gave him an A. In all of his courses, Dada Trash tended to get either an A or an F. There was no middle ground when it came to reactions to his work which pleased him to no end. Dada loved extremes and craved convulsive reactions. His greatest fear was that someone would find him boring or middle of the road. Even profoundly negative reactions were cherished. If someone reviled his work to the point of wanting to destroy it, Dada Trash took that as a supreme compliment.

One time Dada entered one of his more disturbing pieces into a group show. The work was a collage made from S/M porn mags and photos of deformed genitalia clipped from an old medical textbook called Sex Errors of the Body. Along the bottom of the piece he had written “Every Act Of Tenderness Is A Prelude To Violence” in his own blood.

One of the judges became so enraged at the collage that he ripped it down off the wall and threw it away.

“It all comes from the garbage can, and to the garbage can it all shall eventually return,” Dada said afterwards. “My whole life, everything I've ever done, it just pisses people off. The only thing my art does is make people angry.”

He said this with a certain sadness and pride in his voice.

I first met Dada Trash aptly enough on Halloween. We were both in our sophomore year of college. Dada had gone out as “Surrealism” and his face was painted with interweaving images of leaves and fish. Styrofoam cups were krazy-glued all over his body and he carried a giant wooden fork and spoon as dual scepters. I liked him immediately.

The two of us soon began to collaborate on a series of Super-8 movies. They were art flicks. We would have done porno loops but me and Dada Trash couldn't find any girls who would take their clothes off so we had to pick topics that were closer at hand. Like our film Meadow Muffins which was a documentary about piles of cow shit in various fields around Delaware. Another documentary called Hygiene consisted of one ten-minute shot of Dada Trash popping the numerous zits on his face into the camera until you could barely see through the lens. By the time we finished screening that one, not a single person was left in film class, and five students and the professor were in the bathroom driving the porcelain bus.

Our ultimate Super-8 epic was called Dad! True to the spirit of Sergei Eisenstein, it was a silent film. Dad! opens with a shot of the red evening sky. Slowly the camera pans down till the screen is filled by a gaudy neon lit porno shop. A nervous young man about twenty years old walks into the place. Inside, he glances at the magazines for a few moments, then makes his way towards the peep show booths in the back. There is a dim shot of the boy walking down the hallway of doors. Scuzzy men in dirty raincoats shuffle past. Illuminated signs on the doors advertise the movies showing in the booths. Swamp Pussy. Hot Buns for the Baker. Pumping Granny. Enema Antics. The young man picks a booth and walks in. The camera zooms in on the sign on the door: Journey to the Center of My Bunghole.

Inside the booth there's a shot of the young man from the chest up. The light from the film flickers on his face contorted in ecstasy. His arms move in a way that suggests the boy is jerking off. Then the camera pans over to a glory hole drilled in the wall. A hand pokes through the hole and starts beckoning to the boy. The young man's bliss is suddenly interrupted as he stops and stares at the hand. It begins making obscene pantomimes of jerking him off. There's a shot of the boy's face in deep, perplexed thought. Cut to a black screen with white words that say: “Even though I'd never actually done it with a guy I'd always been tempted… Ah, what the hell!”

The young man gets up and sticks his dick into the glory hole. There is a long shot of him from the shoulders up, his face going through ever higher levels of bliss as the invisible man on the other side of the wall sucks him off.

Cut to a shot of the two adjoining peepshow booths filmed from the outside. Both doors open simultaneously and the occupants emerge at the same time. Suddenly the anonymous lovers see each other. One of them is an old man about sixty who is wiping his lips. The young man looks at him in overwhelming shock and horror. There is a shot of the boy's face as he screams something. Then cut to a black screen with the single word: “DAD!” in big white letters. The End.

Needless to say, that one didn't go over too well with the film department either. I think both of us flunked our Cinematography class that semester.

When punk rock came around Dada Trash was finally in his natural element. This was the world he had been waiting for, one where it was fashionable to piss people off. Hell, it was expected. The punks were a culture of irritation. But, of course, Dada Trash still didn't fit in. Conformity would have been death for him. The punks wanted to piss off the world and Dada Trash wanted to piss off the punks. He would go to hardcore shows dressed as a yuppie or a Marine, just to see the reactions he'd get. I had to drag him out of more than a few fights. Dada never did anything belligerent, it was merely his clothes and appearance that caused the violent reactions. While everyone was decked out in dark shades, checkered shirts, buttons, and other new wave '80s fashions, Dada Trash dressed in leisure suits, bellbottoms and vintage '70s clothing. Style and Fashion were some of his favorite realms in which to fight his artistic war. Dada loved poking holes in common concepts of conformity and nonconformity. He considered Devil's Advocate a valid career choice.

Dada Trash once had a summer job working for a health insurance firm in Philadelphia. It was one of those horrible office jobs where he worked in a sea of cubicles. His office was just a cramped little square among all the other identical squares. Everyone wore the same three-piece suit, everyone's office area looked exactly the same. The only stamp of individuality, the only way to tell any of the cubicles apart was by the family pictures that everyone put on their desks. Smiling, drooling, cherubic babies, the prune-like faces of grandparents, wedding photos. The gilt-framed pictures were the only humanity left in the suffocating office environment.

In general, Dada Trash hated his coworkers. He thought they were the most boring two-dimensional people alive. So he came up with a little prank to mess with their minds. He went out and got a couple of eight-by-ten gilt photo frames and put them on his desk like everyone else, only he didn't put any pictures in the frames. He just left them as a couple of blank squares. It was great, whenever one of his coworkers would come into his cubicle and try to make small talk, they'd grab one of the photo frames off his desk while saying something like, “So, is this the wife and kids?” Then they'd notice the frames were empty and their narrow conservative brains just could not compute. Sometimes they'd fumble for something to say, but usually there was just an awkward silence followed quickly by them excusing themselves. Dada Trash said it was the best conversation killer he had ever come up with.

His music had an equal ability to annoy. Back in the punk rock days Dada Trash was in thrash bands like Virgin Potato and The Queebs which were so bad that not even the most dedicated hardcore heads could stand them. I watched him play sets that drove away aficionados of industrial noise and experimental dissonance. When he was in Bongwater Enema, they cleared every room they played till not a single club in town would give them a gig. Dada disbanded them in triumph, having achieved just what he'd set out to do. Dada set new lows in musical tolerance. Sometimes his outfits alone were enough to drive an audience away before they played a single note, get-ups that would frighten even Kiss back into their mothers' closets.

“Clothing is art that you can change and broadcast every day, wherever you go,” Dada Trash told me. “Art that's like a second skin. An aesthetic plumage. You become a walking advertisement for yourself.”

A longtime obsession of Dada's was collecting tacky '70s clothing. Pink polyester slacks. Acres of platform shoes. Disco leisure suits. T-shirts with Farrah Fawcett and John Travolta on them. His closets looked like museums of lost fashion, the wardrobe that time forgot. With most of those clothes, there was a reason why they had been forgotten. Dada Trash had a rare talent for buying the ugliest piece of clothing a thrift store or flea market had to offer.

And he wore the shit too, usually in the most clashing and painful color combinations possible. Some outfits were so hard on the eyes you literally had to turn your head away. No matter how you slice it, yellow socks do not go with red vinyl pants. Orange and black do not match, unless it's Halloween. Some days Dada Trash reminded me of a surrealist clown, a time traveler with really bad taste.

Like one night in the Haight when we walked down to the grocery store. Dada wore a fuzzy white yak hair jacket, wraparound neon orange shades, powder blue crotch-hugging polyester pants, and a pair of pink suede clogs with six-inch platforms. While we were walking down the sidewalk an old black woman did a double-take and said, “Man, you some kind of pimp who just got out of the joint after being in since the '60s?”

“No! He's Bootsy Collins!” I said.

Another time back east the two of us were at a Residents show in New Jersey. Everyone in the crowd was a stereotypical late-blooming punk rocker, or dressed down in basic black. Dada, on the other hand, looked like some glow-in-the-dark used car salesman. He wore a fluorescent orange and yellow polyester leisure suit with white bowling shoes.

“Have you noticed?” he asked me at one point.

“Noticed what?” I asked.

“Nobody's caught my look yet,” Dada said proudly. “I'm still the first person to be into the retro-'70s look.”

“Buddy,” I said, “nobody's ever going to catch your look.”

But I was wrong. A few years later there was a '70s revival. I guess it's just a matter of time before everything comes back.

Dada knew that, which was why he was stockpiling the '70s. It was all part of his master plan. Back in the '80s we were sure that the president, Ronald Reagan, was going to blow up the world any minute, and Dada Trash had already formulated a contingency plan for the day after. He would warehouse the largest stockpile of '70s clothing known to man, a motherlode of polyester. Then, after World War III, he'd sell it to the survivors. Not only would he get rich in the new economy, but he'd also control the fashion trends of the post-apocalyptic world. “After they drop the bomb, the '70s will return forever,” Dada concluded.

By then Dada's artwork had passed beyond the mere tangible materialistic uses of trash and into the refuse of ideas. “Some of the stinkiest garbage on this planet exists in people's minds,” he said. Dada became fascinated with trash culture, disposable media, lowbrow trends and fads. “The main product of a consumerist society is garbage,” he reasoned. By then, a lot of his art wasn't even an object, but an idea or event. Sometimes he just set things in motion and watched where they went. Dada brought his sense of play to this conceptual stage of his career and all reality became his palette.

For example, Dada Trash used to play bass in a '70s cover band called 1-800-GET-DOWN. They did a great psychedelic version of the theme song from Charlie's Angels. The band was known for elaborate staging that highlighted the members' bizarre collections of vintage polyester clothing and elevator shoes. 1-800-GET-DOWN turned out to be enormously popular but just when it seemed like they were going to make it really big, the lead singer's ego got out of control and he broke up the band.

Afterwards, Dada Trash realized that what he had liked best about the music industry was making the press kits, those bulky brown mailing envelopes full of publicity photos, newspaper articles, and demo tapes that groups send out to clubs and record labels to try and get gigs. Dada Trash loved to put those together. So even though he wasn't in a band anymore he kept making press kits as a kind of conceptual art project. He still had a lot of weird outfits left over from 1-800-GET-DOWN and he would mix and match these on his friends as they posed for group photos. Dada recorded the demos on his four-track and used different distortion devices to change the sound of his singing voice.

One of my favorite press kits was for Billy Buttfuck and the Bacon Strips. They were a gay country and western band that sang about family values. One of their songs started out with Billy drawling in a thick Texas accent, “It's time to fry, boys…” The promo also claimed that Billy switched into cowgirl drag for his medley of tunes from Annie Get Your Gun.

Another great one was the press kit for Lee Harvey Osmond and the KGBeeGees. They were a group of Oliver Stone impersonators who did Bee Gees covers while dressed in outfits that used to belong to Donny Osmond. Dada even wrote a fake newspaper review that raved about their album “P.C. TV and the Single Gun Theory”.

Dada Trash also had this press kit for a lesbian band of Elvis impersonators called Butch Van Dyke and the Beaver Patrol. They could also perform as a Stray Cats imitation/ cover band. The funny thing was that all the dykes in the band promo photos were actually Dada Trash and my friends Roth Forjic, Sam Silent, and Zeke Moon in reverse drag as dudes.

These bands proved to be enormously popular (much more so than my friend's real band had ever been) and Dada's answering machine was soon clogged with calls from ecstatic club owners who couldn't wait to have them appear. But of course they never did. Some club owners were still so eager have some of them appear, especially the KGBeeGees, that they kept calling up and pestering Dada Trash. He finally had to pretend to be the bands' manager and tell the promoters that the groups had suddenly been killed in a plane crash or their yachts had disappeared in the Bermuda Triangle or something. This did nothing but elevate their fame.

To top it all off, a couple months ago I saw the group photo of Billy Buttfuck and the Bacon Strips up in the hallway by the bathrooms in Slim's. It was framed and hanging next to pictures of all the other famous groups that had played the club. When I asked the doorman about it he said they were the best act that had ever played there. Dada Trash had evolved from a garbage artist into a reality artist.