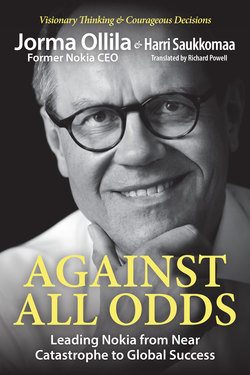

Читать книгу Against All Odds - Jorma Ollila - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 9

Student Leader

IN THE AUTUMN OF 1972 I attended the annual conference of the National Union of Students in Finland, the SYL. I was elected to the board and appointed president. We gathered on Friday, held our conference on Saturday, and on Sunday we wondered what on earth we had decided. Formally we were there as representatives of our individual student bodies; I represented the students of the University of Technology. But the elections were nakedly political, as everything was at that time. The talk in the corridors was that a centrist candidate should become president, because neither a conservative nor a leftist would receive broad enough support. The night before the actual elections was key because the crucial politicking took place in the small hours. The search was on for a centrist candidate for president who would be acceptable to everyone. I fitted the bill. Also during that night we drew up an outline program for the coming year, so there were arguments about that as well. It was like drawing up a government program in the space of an evening.

On Sunday I set off on the long journey home knowing my life was about to undergo a major change. I had been elected president of the National Union of Students at the age of twenty-two. I had been the chairman of the National Union of Technology Students, so I had some idea of how to run things. I had for example helped organize boycotts of lectures, intended to encourage the modernizing of university governance. As students we demanded that we should be directly represented on the governing body.

Now I would be advancing students’ interests full-time. My new role had a significant international angle, so my studies abroad and language skills certainly helped. When I was appointed I felt the glare of publicity for the first time: the selection of a new student president made the news in the big dailies and even on television. Suddenly I was a figure of national significance. My parents were bemused; they didn’t feel this new career path was either desirable or suitable.

Just half a year into our marriage Liisa had to adapt to the fact that her husband was no longer a student. As president I received a small salary, which largely went on rent. The SYL was based on the fifth floor of a fine building in central Helsinki called the New Student House. It opened on to Mannerheimintie, Helsinki’s main thoroughfare. For the first time I had my own room to work in.

I went into the office in the morning and came home in the evening, just as in any job. My studies were on hold. I still have two exercise books from that time and the pages are blank: no academic studies for four terms. I wore a suit and tie every day and carried my briefcase to the office and back. Many evenings were taken up with negotiations, meetings, and travel. Everything was in earnest and over-politicized. I took myself very seriously and it seemed as if I were aging very fast in my role. The union was well run, both bureaucratically and financially. The secretaries were highly professional and kept youthful enthusiasm in check, whereas the executive board was of variable ability.

At that time the SYL was seen as a natural springboard to a career in national politics. For example, Tarja Halonen – later president of Finland – had been on the board only a couple of years earlier and later moved via the trade union movement into Parliament.

I wanted to be a student leader, and I enjoyed my work. I often used to travel to universities around the country. I was constantly in meetings with senior officials and government ministers. But I never actually saw myself as a politician, rather as someone whose role was to speak up for students.

I enjoyed working in an organization with a small group of people. I wanted to lead it effectively. Meetings should have an agenda, objectives, and a clear timetable. I wasn’t interested in publicity and I didn’t seek it, though I did get my first taste of it, which came in handy later. I learned to make speeches entirely spontaneously, which hadn’t been among my strong points. I also learned to write long, carefully considered speeches whose official line corresponded with Finnish foreign policy. I have never liked compromises, but as a student politician I had to make them every day – a tedious but also educational side of the job.

Sometimes my impatience rose to the surface. Even on a good day, running the National Union of Students in Finland was a constant defensive operation: the rise of the communists and the growth of their power had to be stopped. Although the Left didn’t have a majority, at that time it felt as if there was a real danger that it would take over the entire student world. In many European countries student bodies had become radicalized, and the majority of students were alienated from them. That was what happened in France, for example. Preventing it happening in Finland became a mission for the Centrist group in Finland at the SYL.

As the representative of the Centrists I also had to cooperate with the Conservatives, though many issues were resolved with the Left. The Left and the Centre formed the so-called pan-democratic front, which held power. Even so, while I was its president the SYL never signed the declaration against the Free Trade Agreement with the European Economic Community. There were strident demands for the agreement to be rejected – people who would later hold important positions such as Tarja Halonen (later president of Finland), Erkki Tuomioja (later foreign minister), and Erkki Liikanen (governor of the Bank of Finland) all actively opposed it. In important questions of foreign policy, where relations with the West were at stake, the SYL stayed firmly behind agreed national policy.

I learned the rules of the political game. I had been the agreed choice of the Centrists and the Left for my role. In some issues, after careful deliberation, I voted with the Conservatives to promote what I believed were sensible policies. This irritated the Left and some Centrists too and gave rise to accusations that I was an opportunist and a turncoat.

Learning politics from the inside was an enormous help later on: leading a student organization in Finland in the 1970s certainly taught me what politics, discussions, rhetoric, horse-trading, and opportunism are. A CEO has to understand what politics is all about, otherwise the company will start to misinterpret its environment, which is the society it operates in. The consequences could be fatal to the company because you usually can’t change your environment – you have to adapt to it instead.

The main reason the president’s job was energy-sapping was the Stalinists. They were self-assured and knew what they wanted. Others piled in behind them. They followed a twin-track policy. On the one hand they took the parliamentary route, actively and aggressively exploiting the SYL’s position and resources. On the other hand they were trying to bring about a revolution. This pincer movement was very hard to fend off. Relations with the Soviet Union were ruthlessly exploited as a pretext for change at home. My own attitude took their support as its starting-point. When a group has about 15 percent support, an organization like the SYL has in fairness to give it a hearing.

It’s good to remember that the Stalinist movement received more attention than its level of support merited. In parliamentary elections it received only a few percent of the vote, though the figure was higher in student elections.

Finland was led by Urho Kekkonen, who had been in office since 1956. He was the chief architect of the country’s foreign policy and the guarantor of Finnish independence vis-à-vis the Soviet Union.

The popularity of his policy was growing in the early seventies, both among the electorate and in political circles. It was largely thanks to Kekkonen that Finland had been able to negotiate a Free Trade Agreement with the EEC; this was important for Finnish export industries. In January 1973 Kekkonen’s term of office, due to expire in 1974, had been extended by an exceptional act of parliament to run until 1978. This was no foregone conclusion, since it required five-sixths of the members of parliament to vote for it. It was intimately linked with the EEC Agreement and new laws extending the state’s regulatory powers, which the Left in particular supported.

Kekkonen and Finnish foreign policy also enjoyed respect in the West. Finnish neutrality was widely recognized, but many western politicians and journalists never fully understood just what a tightrope Finland had to walk during the Cold War. The president had bitter enemies back home as well, who publicly accused him of kowtowing to Soviet wishes and thus of Finlandization.

I met Kekkonen a number of times. Most of these meetings were formal occasions, but I also went to his official residence to discuss issues such as the reshaping of university governance. We explained the SYL’s standpoint to him. Kekkonen’s position in Finland was so dominant that people involved him in issues that weren’t really his responsibility. He was vigilant and engaged and concerned above all with power politics. How did the parties divide over the issue? How did politicians’ public statements reflect their personal goals? These were some of the questions he put to me during our discussions.

My most memorable meeting with him was at the Independence Day reception in December 1973. It was the custom for the Students’ Union to present its greetings to the president before the main event. I had prepared a few words requesting the president to focus attention on the serious shortage of student housing. As I walked toward the Presidential Palace it felt as if the damp Helsinki streets were soaking up all the light, despite the Christmas decorations in the shop windows.

We met the president at half past six, half an hour before the official reception started and a stream of guests would flow into the state rooms. Our meeting was naturally a terrifying prospect. First there was the age difference: Kekkonen was fifty years older than me – a very fit seventy-three, and he didn’t show any sign of the dementia that would afflict him a few years later. Secondly there was Kekkonen’s unassailable position, which younger generations find impossible to understand. He had been president since I was five and would carry on until I was thirty-one. It was almost unthinkable that anyone else could be president.

Liisa and I at the Independence Day reception in 1973 with Finland’s finance minister Johannes Virolainen and his wife Kaarina.

We were a small delegation who arrived at the gates of the Palace and were directed inside. The others, in the spirit of the age, were wearing lounge suits, but I was correctly attired in full evening dress. Frankly, it wasn’t all that comfortable. The walls were hung with fine art depicting Finnish forests and wildlife and historical battles, though this wasn’t the moment to embark on a course in art history.

We entered the room self-importantly and in line with protocol. The president stood waiting for us with an array of decorations pinned to his chest – Finland, perhaps surprisingly to some, has a flourishing honors system. He looked at us fiercely through his large, intimidating spectacles. He had an adjutant on either side. As one president to another, it was my duty to offer him our salutation. “Mr. President of the Republic, Happy Independence Day,” I began. We also offered him a little bouquet of lilies for his wife Sylvi. The president accepted the flowers and I thought I saw the ghost of a smile. “Thank you, I shall make sure immediately that these reach their intended destination,” he replied. It broke the ice. After that I made my little speech.

As the SYL president I had also been invited to the real reception. So after our brief meeting one of the staff guided me around the side of the Palace to join the queue to shake hands with the real president, while he went through the state rooms to the head of the receiving line. There Sylvi, whose health was already starting to fail, was sitting waiting for him. He gave her the flowers and started to shake the hands of his guests for the evening.