Читать книгу Called Home: Our Inspiration--Jim Mahon - Joseph A. Byrne - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 GREATER FORCES

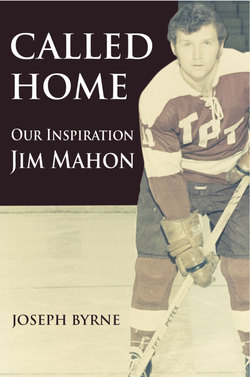

ОглавлениеThey were quite a sight those Peterborough Petes of 1971, as they formed their honour guard, there, in front of the Stewart L. Kennedy Funeral Home, in the Town of Essex. The Petes were a legendary team, loaded with talent. They were, after all, the team of Jim Mahon. Their appealing maroon colours would have flown high on another occasion. Now, they served as mere backdrop.

The veteran sniper, Rick McLeish, was there. He was by now, a Philadelphia Flyer, a team that coveted his well-known toughness and scoring ability. He looked strong and handsome there in front of Kennedy’s; fitting for the lot he had been given in life. Yet, even he was somehow dwarfed by these circumstances.

The goaltender, John Garrett, was there. John would recall through the mist of his thoughts, how a Jim Mahon shot would hurt even when it hit on the center of the goal pad. But nothing had ever hurt like this.

Doug Gibson was also there. This man, known as an artist with a puck, who together with Paul Raymer, were line-mates with Jim, men who were determined to let the full extent of Jim’s talent show, were now called upon to give him their greatest assist. Future NHL’ers Ron Lalonde and Danny Gloor, stood attentive.

Inside the funeral home, the captain Craig Ramsay, at times exhibited his legendary leadership abilities, remaining strong and composed. His leadership was vital now for the sake of his teammates, who were completely bewildered in this sad environment. At other times, Craig would lead in a very human way, his overwhelming sadness showing through. He and the stalwart defenceman and future captain Colin Campbell, a player toughened by years of hard work on his family’s tobacco farm near Tillsonburg, would, at times, exchange glances. Both of them welled with tears, unable to speak at times, as they stood there in this environment of complete shock.

Jim’s roommate, Bruce Abbey, who had been to the Mahon farm many times, and who was there on Jim’s last day, training with him, was transfixed. He had been a tower of strength to the Mahon family in the immediacy of that cruel day, not allowing himself to properly grieve, staying as strong as he possibly could, for the sake of the Mahon family. He had earned his moments now.

These men were joined by teammates Ron Plumb, Paul Perras, Dennis Patterson, Coach Roger Neilson and Maidstone teammate Bill Bellaire, who had gone with Jim on that great journey to Parry Sound to try their hand at junior hockey.

By all accounts, these were remarkable men. They had earned their accolades, and they wore them well. Now, they took on their greatest job. It was left to them to carry Jim’s body toward the honour guard, which had been set up by their Peterborough teammates. All of them were stars. They had sought stardom. They had earned it, but not this kind of stardom. They all had, indeed been cast in this enormous spotlight, a spotlight which now shone on them, but not of their choosing. None of them had ever experienced anything like this. Nothing they had ever done had prepared them for this.

There was an eerie silence then, there, broken only by muffled sobs and a solitary bell sounding in the distance. Bong—Bong—Bong.

The coach, Roger Neilson, stood guard with them, trying desperately to look strong, composed, intelligent, and in control. He wanted to look that way for the sake of his young men. Roger desperately wanted to look strong for them. He had always sought to represent the higher ideals in hockey, as in life. Roger was always mindful that there were higher ideals in hockey. Now, he was given a chance to demonstrate those higher ideals, to lead his young men, his talented young men, the Peterborough Petes. Yet, even Roger, this deeply spiritual man, this man who loved God, gave in, as both of his eyes misted, forcing him to dry them in plain view with his white handkerchief. Roger would stand there with his white handkerchief in hand, as though in surrender to his world, to his God, to the people who were there, to the greater forces around him. But now, Roger waved it symbolically as though in surrender. Roger would one day use that white handkerchief to great effect in hockey too, symbolic perhaps of that day, that very sad day.

The Petes stood there, handsome on this day, in those two straight lines facing each other; so much so that on another day someone surely would have made remarks about it. All of them looked straight ahead, unable to make eye contact, afraid to make it, except to sniffle, or shield their eyes from their tears that fell, or to imitate their coach and dry them. It was silent that day—far too silent.

This who’s who of hockey stars and stars-to-be were in submission in this bewildering environment.

Still, they waited there, lined up at the foot of the steps outside Kennedy’s Funeral Home, forming their honour guard on the pathway that led to the hearse waiting there quietly, on Main Street. Bong went the bell again. Bong—bong—bong.

Inside, the veteran funeral director, Stewart Kennedy, a leader at sad occasions, couldn’t keep his composure either. He too sobbed, mostly keeping it inside, looking away when he needed to, drying his eyes when he had to, rushing away at times, as though on an important errand, when the emotions were too strong, he too using a white handkerchief to dry his tears, to surrender.

The surrender was more than symbolic that day. It was real, much too real.

It was remarkable by all accounts. Inside, the stifling silence was broken by the suffering of his parents, Ed and Maxine. Both of them were dying right there with their son. They both needed assistance to even be there, yet both of them were unable to leave.

Ed and Maxine both lived through the experience of having their lives ended at the moment their son, their star son, had died. Yet, both of them were forced to continue living for the sake of their other children. Maxine would be the signature of that submission.

“God!” she would say. “I have done my best to raise my children until now, but I am now unable. You will have to raise them for me now for I am unable,” she would repeat.

It would be her heartbroken children, led by the eldest, Judy, and by John, Joan, Dan and Kathy who would pull together to make God’s job of raising them easier.

Ed and Maxine were destined to lead the first family of hockey, but that didn’t matter now. To be with their son Jim, is what mattered. It was all that mattered. He looked handsome there lying in his coffin. How we desperately wanted him to again sit up and let his greatness show. Now, he would again include us in his many victories as he always did, never leaving any of us behind, making it look so easy to win at hockey as at life, and to make it look so easy to bring all of us along with him to share in the joy of those victories, in the joy of who he was—this great man.

The family and all of us too, experienced death that day. We experienced it with our great friend, Jim Mahon. A part of us died with him. We were on our own now, cast out from the cocoon of his greatness, and we didn’t want to be.

Members of the Hayes and Mahon families were there to help Ed and Maxine, but, they too, were stricken by grief, immobilized by it. At that moment, that very cruel moment, when the coffin was closed, they too, were unable to cope under the strain of it. Time would stand still that day, and yet it would move on, cruelly move on.

Ed stared straight ahead, as though looking at his son one last time. And there he was—his boy—his well-loved son. He could see him now in his mind. Now, he was standing there before his eyes, standing on one leg, balancing himself there at the rink as he pulled on a skate. He bent over it, laced it up in the way he always did, then starting with the bottom loop, tightened it, and then each next one in succession, before tying a first shoe knot, then a second to reveal two perfect loops. He then pulled on the other skate and effortlessly tied it. Even in this simple task, his immense power showed. There it was, the muscular frame of a giant of a man, still a boy.

Then in one powerful smooth stride, he glided away onto the smooth ice.

“Man! He’s back!” someone shouted out from the haze as he smoothly skated on. He circled the rink a couple of times, then skated backwards, just as smoothly, just as powerfully.

Next, he did some stretches, before reaching for a puck, fondling it with his stick and doing things with the puck that would remind one of a magician with his wand. He pulled it back and forth, side to side, through his legs before quickly releasing a wrist shot to the bottom corner of the net. Even Ed lost sight of the puck as it sailed through the air, only to reappear when it had bounced out of the net, to settle again on his stick.

There was a magic to hockey, the way Jim Mahon played it. It was there, at that moment, as it had been on most others when Jim played. It was the same magic Jim had shown his father and all others who had watched him over the years. It was a magic Jim had shown them over and over, again and again. Yet, it was so different now for Ed, and for all who were there then. This was the last time they would watch Jim, even if now, they watched him in their minds because until the coffin closed, he was there with them. It was the last time they would watch him in their minds, with his body present. Jim was still there. Jim lay there, still looking like he would get up from his terrible sleep, and resume the heroic role that God had given him until now.

But then, the coffin was closed.

People rushed to help. They tried to help. But, how can you help when there is no solution to the problem?

His old juvenile coaches were there, Lonnie Jones and Jim Barnett, both of them wishing they could help. It had been easy for them until Jim died. The solution in every situation had been so simple. It was as easy as this.

“Jim, get onto the ice,” is all they would have to say, and the solution was at hand. They, too, were heartbroken. They had coached him as a kid playing in a juvenile league, playing like a man would have, despite his tender years. He had made the Maidstone Green Hornets, a super team, a team that was larger than life. They too, were paralyzed by grief, disconsolate in it. They too, had lost in their personal struggle with the grief they felt for Jim. Their suffering was brought on by what Jim had meant to them, to their loved ones, to their community, to their country, to every one of us, to what he was, and to what he would have been.

Each one, that day, had sought to find earthly meaning in this tragedy. Each one had failed to find it, and now, each one was trying to join with Jim spiritually; at least, to join with him in their minds, in another world; at least to join with him as close as they could get to him. All who were there that day at Kennedy’s Funeral Home tried to join with Jim, tried to join spirits with him in that other world, all the while living out their earthly suffering.

Despite the magnitude of the attendance that day, and despite the quantum of dignitaries there, this was not a celebrity spectacle, though celebrity it surely was. It was a spectacle of pure grief.

All the while, a lonely distant bell punctuated the silence. Bong! It sounded in mysterious undertone, barely audible. Bong! Bong! It continued, leaving pure silence between strikes, as though, it too, waited for him to awaken. Bong went the bell again, perhaps from St. Mary’s Church in Maidstone, where Jim was headed next, perhaps not. It continued throughout the funeral mass. Bong! Bong! Bong! It felt like a heartbeat, Jim’s heartbeat, the heartbeat of our community, and all that was good in it.

Inside Kennedy’s that day, it was left to another, muscular, young farm boy to salvage for us some sense from this — any sense. He too, was a popular young man, now a priest, called upon to do the impossible. He was a farm boy too, who had grown up in Pleasant Park, the same suburb of Maidstone as Jim had grown up in. In fact, their farms touched each other at the back, separated by a small ditch. He lived on the Sixth Concession, his deceased friend on the Seventh. The pond that Jim skated on in his youth actually bordered the priest’s farm. In fact, Father Chris Quinlan — Father Chris to all who knew him, used to skate on that same pond from time to time. The Quinlans and Mahons were like family.

To call Pleasant Park a suburb is really a grand overstatement. Maidstone itself was farm country, and that neighbourhood was primarily an old Irish settlement of mostly farmers, with popular Irish names like Mahon, Quinlan and others like Hayes, Shanahan, McGuire, McLean, Barnes and a dozen others characteristic.

This Quinlan man had chosen a life dedicated to God. This man of remarkable character had been ordained a priest a short time ago. This man was now chosen by the family—by God—to explain this to us. He was not merely chosen to do it. He was charged with a duty to do it, charged with God’s duty to make sense of this for us, to make sense of this for heartbroken people, aching people.

But how could he? How could anyone make sense of this? How could he even speak of it?

He began by saying, “Dear friends…” then, pausing before saying, “Jim Mahon,” and then silence set in. There was then a pause, followed by another pause. The pause lengthened before it lengthened some more. Something happens to time at moments like these, as it happened here, this day. There is icy silence on occasions like this that turns seconds to minutes, and minutes to hours. Father Chris composed himself, as he let the silence continue. He would try one more time, then capitulate, and let the course of it play out.

Jim Mahon meant that much to all of us. The silence told it all.

This was by no means the first time that Father Chris had been immobilized by this grief. The family had asked for him at the moment of Jim’s death, at that terrible moment.

He was doing parish work at his parish, St. John Vianney, in big city Windsor, when the desperate call came in.

“Father Chris,” the anonymous caller implored. “There has been a terrible tragedy. You are needed there immediately.” The caller, Jeannette Sylvester, hung up the phone without giving further details. Father Chris would know her voice well. Introductions should not be necessary in this climate of urgency.

Father Chris left at once, not sure who it was that needed him, but he was on his way. He sped out of Windsor at the fastest possible speed. He flew down the 401, a relatively new highway, getting off at Manning road, taking it south to the North Rear Road. Then, he headed east on it.

He was planning to go to the Quinlan homestead to ask if they knew who was badly in distress. Then he knew. The many cars at the Mahon residence gave it away. Father Chris knew at once.

“Good Lord,” he said out loud. “It’s the Mahons,” he said as he blessed himself, and at once prayed that God would give him the strength to help. As he sped into the Mahon driveway, he was speechless.

“I never saw so many people in need of help,” he would say later. “I didn’t know who to minister to first.”

There were 50 or 60 people there, and every one of them was immobilized with grief. Many members of the Hayes family were already there, all of them disconsolate. Jimmy Hayes, the uncle for whom Jim was named was especially lost here this day, even blaming himself, wishing he could trade places with his hero, his nephew, his pride and joy.

“It’s Jim,” someone said finally. Father Chris stopped in his tracks.

“You can’t mean it,” he nearly said, and if it was a different occasion, he too, would need counsel to deal with the tragedy. Instead, he prayed to his God, the God he loved. He prayed for strength that day, for he would need the entirety of God’s love at this exact moment. He would need every ounce of strength he could gather from his God, to even continue now. He would need all of it, and he would need it now. He prayed to his own deceased mother, who had always been his inspiration. He also prayed to his late father for strength, the strength he had inherited from him.

As he had sped into the farm yard with the many carloads of people already there, and more arriving with each moment, the young, heretofore confident clergyman was completely taken aback. How could anyone possibly make sense of this tragedy? For how could God have revoked that great gift that he had given to this family, to this community, this gift that was Jim Mahon? How could God possibly have revoked that great gift?

And then he was called upon to walk into that suffering house to hug and to hold Ed and Maxine. Words were useless now. And what could he possibly do for the suffering Mahon children?

All the while, Jim’s close friend from the Petes, Bruce Abbey, sped back down the 401 from London to the Mahon farm. He had just left that farm mere hours earlier, speeding to London from it, for work after a morning of training with Jim. He had, in fact, left a mere hour or so before Jim’s death.

“It couldn’t be true,” he said on arrival in London. “I was with him an hour ago.” Bruce would be a tower of strength for the family that day, as he had been for Jim.