Читать книгу Called Home: Our Inspiration--Jim Mahon - Joseph A. Byrne - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

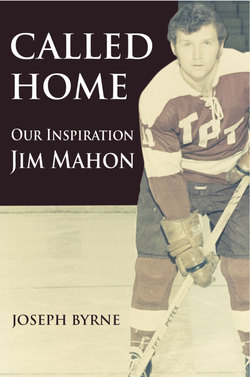

2 A COMMUNITY’S SUPERSTAR

ОглавлениеThe phone rang. It was Ed Mahon, a man of few, but well-chosen words.

“Mrs. Byrne,” he said, “you had mentioned that I could call you if Jim ever needed a ride to hockey, and I know you do groceries at Sadler’s on Saturday’s. Is there any chance you can give Jim a ride to the rink today?”

“Sure, I would be happy to,” my mother said in her Lithuanian accented English. “I’ll come right over.”

My mother grabbed a sip of her tea, put on a light jacket, grabbed her purse, and burst out the door. She opened the door to her car, an older Corvair, sat down, and turned the key to start the ignition. The engine didn’t roll over. She tried again. Again, the engine sat in silence.

Just then, our neighbour Amie drove in with the other Corvair, the one he had used to give my mother driving lessons. Amie had told her, “Corvairs need a lot of fixing. You had better get two if you like driving them, so I can fix one while you drive the other one. I will only charge you for the parts I have to buy, that is, if I can’t make them myself.”

The system worked perfectly, and this was a prime example of it. “Hello Amie,” she said, “I’m in a bit of a hurry.”

“Here are the keys,” Amie replied. “What’s wrong with this one?” he asked.

“It won’t start,” my mother replied.

“The alternator must be gone again,” he replied. “You better go,” Amie said to remind her that she was in a hurry, “and drive carefully,” he added.

“I will, Amie,” she replied. My mother sat down in the other Corvair. “Good bye Amie,” she called as she shifted it into gear, and drove out the laneway. She pulled out onto the North Rear Road, heading west, in the direction of the Mahon farm, two roads over. She drove fast for a Corvair, its oscillating steering having a mind of its own. The Corvair was hard to steer in the best of circumstances, but on a gravel road like the North Rear, it was a constant effort in correction, and over-correction.

My mother hurried along, for a distance of about a mile, to the John Zack farm. She looked left, at the side road there that backed onto the North Rear Road. She looked in the direction that led first to Sacred Heart School, which Jim attended. That road also led to the Town of Essex.

Ahead, she saw a young man running with his hockey equipment in tow, and a hockey stick in hand. She turned down the road, on a hunch it might be Jim, sped up a little, pulled up beside the lad, who was now in full sprint.

“Do you want a ride?” she asked.

“Sure,” Jim replied, “I’m late for hockey.”

“Let’s hurry then,” my mother replied as Jim ran around to the back of the car to put his equipment in the trunk. My mother called out, “This car is a Corvair. They got mixed up. They put the trunk in the front of the car.”

“Oh yeah, I should have known,” Jim replied as he ran around to the front of the car, put his equipment into the trunk, not able to fit the stick in, pulled open the door on the passenger side of the car and said, “is it alright if I bring my stick into the car?”

“Sure,” my mother replied as she watched him squeeze his large muscular frame, though yet he was only a boy, into the front seat of the car. “Sure,” my mother replied. “It won’t hurt the upholstery,” she said intending to make a joke, as the car was old-looking, and dusty from travel on the gravelled country roads. Jim hesitated, not wanting to offend her. “Please,” she said, “bring your stick in, or I will be late for groceries.” Jim laughed as he pulled the car door shut, and they departed for Essex.

Not much else was said until they were part way down the Naylor Sideroad, heading toward Essex. My mother didn’t know a lot about hockey, but she was interested in it.

“I heard you are a good player,” she said to him finally.

“Oh, I don’t know,” Jim replied. “There are a lot of good players, but I try hard.”

“Good,” my mother said as they pulled up to Essex arena. “Have a good game.”

“Thank you for the ride,” Jim called back. “I’ll try to score a goal for you,” he added, “maybe two.”

My mother shot back, “yes, maybe score two goals.” Jim only smiled as he hurried to the front of the car to get his hockey equipment out of the trunk. “Do you need a ride home after groceries?” she asked.

“No,” Jim replied, “my parents will be here.”

“Good,” she replied and drove away. Jim didn’t know that his parents would be there. They always tried to be, but today was one of those days when they weren’t sure if the car would be fixed in time to get there. But it didn’t matter greatly to Jim, except that he loved to have them there. To run the seven miles home after the game, even lugging his equipment, would be child’s play for him.

Inside the arena, Jim hurried through the lobby of Essex arena, down the corridor, stopping briefly at the water fountain for a drink of water, slowing down at the swinging doors to open them slowly, before walking quickly to Dressing Room Three.

Outside, his coach said, “We’re glad you’re here. We thought we would have to send the posse out to look for you.”

“Sorry coach,” Jim said as he opened the dressing room door and went in.

Inside the room, everyone knew Jim had arrived as soon as the Corvair had pulled into the driveway at Essex arena. Several members of the team saw him riding in the front seat of the Corvair, as it made its way to the arena door. The team had posted a watch for him. It seemed that everyone in Essex knew when Jim Mahon arrived at the rink. The atmosphere in the rink would change, the moment Jim came in. You could feel his greatness, even as he walked into the rink. It wafted as though through the air. Everyone picked up on it.

”Nice car,” someone called out, “where did you get it?”

“It got me here,” Jim answered, as he pulled his hockey socks over his shin pads. “I’ve got to score two goals today,” he said finally, “at least two.”

“That should be no problem,” a teammate replied. “You always score two.”

“Well,” Jim replied, “today, it’s important.”

“It’s only an exhibition game,” another teammate added. “Not for me,” Jim thought, but didn’t say.

Jim Mahon was, and had been, a superstar from the time he was a child. Everyone knew it. Everyone felt that way about him. It was a strong internal belief we all had. Everyone felt his greatness, yet no one accorded him privilege. He was simply our friend. He was too big and too powerful, even in Grade One at Sacred Heart School, to be considered a prodigy. And he was too nice a guy to be considered a superstar. “Aren’t prodigies and superstars supposed to have imperfect attitudes?” Even as a child, he was the most humble superstar anyone could ever know. He could simply do it, all of it, not only best, but so much better than the rest of us, that it was beyond belief, and yet he was doing it moment by moment right there in front of us, right there in front of our eyes. Everyone knew he was the best. It was simply a fact. Everyone who knew him as a child had a quiet, intense, strong belief, that he would be the best in the business, whether as a hockey player, or in whatever sport he selected. That was just a fact, as far as we were concerned. No one had to say it.

But to him, we were superstars too. He let us walk right along with him, as though his success was partly ours. That is the way Jim Mahon wanted it to be. He wanted it to be that way so much so, that he took it for granted that we would share in his greatness, a greatness that he didn’t seem to know he had, or if he knew, he certainly didn’t display it. Simply put, we had a chance to grow up with the best. He wanted all of us to share in his successes. He wanted us to share in the glory that was rightly his. In his view, he was simply one of us, a farm boy, a tomato picker, and a real nice kid. In fact, Jim never talked about his athletic exploits. Instead, it was usually us saying things like, “Did you see that play by Jim Mahon?” or “Jim and I had a good game on the pond. Jim got 12 goals and I got one.”