Читать книгу Ali vs. Inoki - Josh Gross - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеROUND TWO

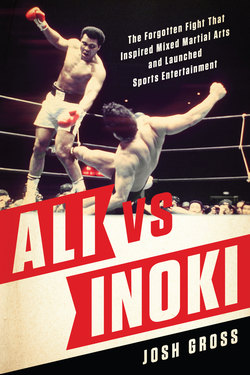

Muhammad Ali met Ichiro Hatta, a fellow Olympian and president of the Japanese Amateur Wrestling Association, at a reception in the United States in April 1975. The story goes that Ali nudged Hatta, an instrumental figure in Japan’s Olympic movement, with a dare: “Isn’t there an Oriental fighter who will challenge me? I’ll give him one million dollars if he wins.” Respected for, among other things, introducing Western-style wrestling to Japan in 1931, Hatta devoted himself to grappling, in the way that Japanese strive to find and repeat perfection over the long course of their professional lives. Therefore, unbeknownst to Ali, Hatta was quite simply the best person to relay his message to the Japanese press, which predictably played up the remark. As it happened, a professional wrestler responded.

There are numerous examples of great wrestlers chasing fights with great boxers. There are far fewer examples of great boxers chasing great wrestlers, but that’s what Ali seemed to have in mind. Ali’s interest in Inoki’s offer hinged, of course, on a massive payday. But his love of professional wrestling, and the notion that the boxer-versus-wrestler debate had not been settled, were quite compelling to Ali. That was particularly true, he explained, because a boxer of his caliber, in his prime, taking on a top-form “rassler” was rare. The possibility of what might happen wasn’t much of a mystery, though. Documented mixed-style fights date as far back as the days of antiquity, when Athens and Rome cradled civilizations, and the results suggested grapplers held a significant edge when allowed to ply their trade.

The influential sport of pankration, a Greek term that translates to “all powers,” is the ancient version of mixed fighting. Mythologized as the martial art Theseus used to slay the Minotaur in the labyrinth and Hercules employed to subdue the Nemean lion, pankration in the real world during the seventh century B.C. blended a mix of unbridled striking and grappling that left all attacks on the table. The wide-ranging barbarism of pankration, save eye gouging and biting, was only too restrictive for Spartan fighters, who, true to their reputation, boycotted competitions unless no holds were barred. The Greeks, however, were on board—it was said Zeus grappled with his father, the titan Kronos, for control over Mount Olympus. Mere mortals became godlike if they found success among the three wrestling forms that rounded out the combat sports lineup at the ancient Olympiad. A quite vicious form of boxing, known for disfiguring faces with fists wrapped in hard leather straps, was also featured as sport.

Until 393 A.D., when Theodosius I, the last man to rule the entirety of the Roman Empire, abolished gladiatorial combat and pagan festivals including the Olympics, pankration created many star athletes celebrated by the Greeks. Mixed fighting held a prominent place in that part of the world for more than a thousand years, yet at the return of the Olympic games to Greece in 1896, bareknuckle brawlers capable of punching and grappling weren’t welcome. Not that it mattered much. These types of fights persisted as humans across a multitude of generations, regardless of the social mores of the day, were compelled to participate in or watch sanctioned violence.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Martin “Farmer” Burns, whose headstone at the St. James Cemetery in Toronto, Iowa, reads “World’s Champion Wrestler,” was the man to challenge. Shy of 175 pounds yet incredibly strong, Burns was the obligatory bear on the mat during his heyday, boasting a twenty-inch neck that allowed him to perform carnival circuit stunts like dropping six feet off a platform wearing a noose, as if he’d been convicted of a capital crime, while whistling “Yankee Doodle.” Burns’ power and skill made him an effective enough grappler into his fifties, handling almost anyone with the “catch-as-catch-can” wrestling style—an influential 1870s British creation that made full use of pinning positions and, absorbing what worked from other parts of the world, a menagerie of painful submissions holds.

By 1910, Burns’ prestige put him in position to work alongside “Gentleman Jim” Corbett—who famously took the heavyweight boxing title from John L. Sullivan eighteen years earlier. The pair served as conditioning coaches for Jim Jeffries, the “Great White Hope” to the generally reviled blackness that was then boxing heavyweight champion Jack Johnson. Say this about Jeffries, the 220-pound banger knew how to assemble a training camp. Burns and Corbett, who in his final fight in 1903 failed to regain the title against Jeffries, are regarded as major influences on the increasingly scientific way people trained their bodies.

During Jeffries’ camp in Reno, Nevada, middleweight contender Billy Papke, a very capable fighter at the time, mouthed off at Burns that a boxer could handle a wrestler, no sweat. Burns quickly offered stakes and a classic wrestlerversus-boxer confrontation ensued.

Eighteen seconds after they met in the ring, Papke’s shoulders were square to the canvas. That wasn’t enough for Burns, who, intent on sending a message, dragged a squealing Papke to the ropes, tied the boxer’s arms behind him, and jumped out of the ring to collect $2,300. As it turned out, Burns was considerably more successful with Papke than he was at preparing Jeffries for Johnson.

With America consumed by the first sporting event to truly dominate public discourse—much more than a boxing title was on the line—Johnson scored three knockdowns en route to a 15th-round stoppage. Race riots ensued and Congress made the transportation of prizefight films across state lines a criminal offense.

Johnson entertained his share of grapplers who wanted a piece, but they never got one, even if he fancied himself a fairly decent wrestler.

Four years after the fight in Reno, Burns published a widely read mail-order newsletter entitled The Lessons in Wrestling and Physical Culture. Ninety-six pages in total, each set of instructions included lessons on body-weight and resistance exercises, as well as wrestling and submission techniques. The pamphlet inspired a new generation of grapplers such as Ed “Strangler” Lewis, who carried on ancient and modern grappling traditions while captivating the public enough to bank at least $4 million over the course of his career.

Such was the strength of the “Strangler” Lewis name that, with a straight face, he attempted during his championship reign to arrange a fight with heavyweight boxing king Jack Dempsey. The public certainly wanted to see it. Lewis’ main challenge came March 16, 1922, in Nashville, Tenn., following another successful defense of the heavyweight wrestling title. “I realize that Jack Dempsey is one of the greatest boxers that ever stepped into a ring, and there is no desire whatsoever on my part to minimize his ability,” the five-foot-ten, barrel-chested grappler told reporters in Nashville, “but I am fully confident that I can handle him, else I would not agree to the match. It is my contention that the world’s heavyweight champion wrestler is superior to the champion boxer at all times, and that wrestling is a more powerful method of self-defense than the boxing art.”

Through the media, Dempsey’s manager, Jack Kearns, accepted the match, and claimed the “Manassa Mauler” was a “first-rate wrestler himself.”

Four days after the challenge was issued, Colonel Joe C. Miller, a rancher near Ponca City, Okla., wired an offer to Dempsey and Lewis for a $200,000 guarantee and split of the receipts if the boxer-wrestler clash was brought to his property, the 101 Ranch, located on the main line of the Santa Fe Railroad. By the end of the year, however, the Oklahoma offer had been cast aside for a $300,000 payday from Wichita, Kans., where wrestling promoter Tom Law, backed by five oilmen, put up money for a bout to take place no later than July 4, 1923. Soon Lewis spoke in the press as if the match had been signed. Dempsey claimed to know nothing of an official contest, even if yet again he suggested he was ready to take on Lewis.

Speaking to the Rochester American-Journal on December 10, 1922, Dempsey noted that “if the match ever went through, I think I’d be mighty tempted to try to beat that wrestler at his own game. I’ve done a lot of wrestling as part of my preliminary training and I think I’ve got the old toehold and headlock down close to perfection. If I can win the first fall from him, I’ll begin to use my fists. But I’ve got a funny little hunch that maybe I can dump him without rapping him on the chin.”

A bold claim considering the competition.

As the first week of January 1923 came to a close, a set of ten rules was released to the public. Two of the ten pertained to Dempsey, who was obligated to wrap his hands in soft bandages, wear five-ounce gloves, and refrain from hitting Lewis when he was down.

The rest restricted the wrestler: a common theme as these matches were discussed.

Among the notable instructions, Lewis could not hit with a bare hand or fist, and strangleholds were barred, as were butting and heeling. To win, Lewis had to pin Dempsey for three seconds. If Lewis spent more than ten seconds at a time on the canvas while Dempsey stood, the wrestler would be disqualified.

While talk captured imaginations across America, the spilled newspaper ink failed to manifest into a real contest. Reports of a signed match were labeled “bunk” by the pugilist. Instead Dempsey turned a desire among fans to see the best from boxing meet the best from wrestling into leverage, agreeing to fight for promoter Tex Rickard on the Fourth of July, 1923. But not against a wrestler. The promoters—oilmen from Montana who originally offered Dempsey $200,000 to fight an unknown opponent and put an unknown boomtown on the map—caved and upped their guarantee to $300,000, the same amount of oil money Dempsey ignored to face Lewis in Wichita.

Two days before the fight, reports indicated that the last of three $100,000 payments to Dempsey had not been made, so the event was publicly cancelled. Dempsey’s money came through at the last minute, but not before newspaper stories were published and 200 ten-car trains riding the Great Northern Railway, totaling thirty-five miles if someone wanted to connect them all at once, stopped running. A disaster. The city of Shelby, population 400, had spent a reported $1 million (nearly $14 million in 2015’s values) to prepare. They laid eleven miles of new track, erected a stadium with sixteen entrances and eighty-five rows of seats on a six-acre plot of land, created a 160-acre automobile tourist camp, issued four hundred building permits, and budgeted city improvements costing $250,000. Grocery merchants within one hundred miles of Shelby were on call to make shipments to a town that now featured more than thirty places to grab food. Drinking booze and beer was legal, and six dance halls were available in the evenings. If anything got out of hand, the governor of Montana, Republican Joseph M. Dixon, was prepared to send in two units of the National Guard.

Since rail was the prime way spectators would have arrived at a newly built octagon-shaped wooden arena scaled for 40,208 seats, ticket sales produced just a small fraction of the expected gate. Dempsey went on to win an uninspired decision over Tommy Gibbons, and the host oil enclave of Shelby, Montana, was forced to endure a historic fiasco. The New York Times called the bout “the greatest financial failure of a single sporting event in history.” Only Dempsey, his manager Kearns, and Gibbons walked away with cash. Everyone else got wiped out. Three banks connected to the financing of the fight closed their doors within a week—bad mojo, perhaps, for Dempsey avoiding the “Strangler.”

Two decades later, Dempsey, then forty-five, stuck his toes in rasslin’ waters. Long retired, he mixed it up as a referee and quickly found himself embroiled in a fracas with a wrestler named Cowboy Luttrell. They settled the matter a couple months later, July 1, 1940, in Atlanta. Wearing the lightest gloves that Georgia officials allowed, Dempsey waited for Luttrell on an overturned beer case in his corner between rounds—a sad sight that did not go unnoticed by newspaper columnists. In front of more than 10,000 spectators, the “Manassa Mauler” smashed the wrestler in a round and a half. Exhibitions in which boxers boxed wrestlers usually rendered down to no match at all. This sort of setup wasn’t grounds for debate. Under similar circumstances, few people would have given Antonio Inoki a serious shot at lasting as long against Ali as Luttrell did with Dempsey. But that wasn’t the paradigm Ali established for his boxer-wrestler foray in Tokyo, and that certainly wasn’t what Inoki had in mind as he hustled to get the fight made.

Smart promoters played up these conflicts, which is why the August 1963 issue of Rogue magazine, an early competitor to Playboy, is still spoken of today. Jim Beck’s article “The Judo Bums” threw down a well-worn martial arts gauntlet by offering a $1,000 prize to any judoka who could beat a boxer. Kenpo karate legend Ed Parker recruited “Judo” Gene LeBell to answer the challenge. “You’re the most sadistic bastard I know,” Parker told LeBell at the judo man’s hardcore Hollywood dojo. The prospect of walking away with $1,000 was incentive enough for LeBell, who didn’t need selling or history lessons to accept Ed Parker’s request.

LeBell fit the bill, for sure. Famous for many things, including handing out thousands of patches to people he strangled cold upon request, LeBell will say that Ed “Strangler” Lewis, Lou Thesz, and Karl Gotch—his “hooker” mentors (pro wrestling speak for legitimately skilled tough guys)—were meaner than he ever was.

“These guys were fanatics,” he said.

The trio represented grappling at its purest, highest class, and each made it a point to prove themselves against top strikers and wrestlers of their day. The historic implications of a grappler fighting a boxer were certainly not lost on LeBell, and a chance to prove himself while defending the teachings of the men who showed him the way was an incredible opportunity.

LeBell’s experience convinced him that competent martial artists should, under pressure, be able to employ a wide variety of striking and grappling techniques. He was ahead of the curve because combining styles wasn’t in vogue while Asian martial arts proliferated in popular culture after World War II. Also, among the folks who trained, the vast majority didn’t fight. That’s why, when LeBell answered Beck’s call, the event poster promised “something new for sport fans.” As a point of clarification, it was new in that spectators likely hadn’t seen anything like it before, well, at least not for a generation or two.

In the aftermath of the Great War, boxer-grappler and mixed-style skirmishes became popular again, though not to the degree they were when jiu-jitsu competitors travelled from Japan to share their knowledge with the world at the start of the 1900s. The judo practiced by UFC bantamweight superstar Ronda Rousey in the Octagon is derived from interactions with folks like LeBell, who studied based on the techniques brought to America by the four “guardians of judo” at the behest of their teacher, judo founder Kano Jigorō, to make Japanese martial arts accessible to the wider world. Kanō’s philosophy was that judo benefits everyone. Mitsuyo Maeda was one of Kanō’s judo acolytes, and in late 1904 he operated out of a gym in New York, taking on exhibitions in colleges up and down the East Coast. Maeda was ambitious, and when throwing strongmen and football players bored him, he searched out more difficult challengers. In America those came mostly from professional wrestlers, who were open enough to incorporate some of the unique skills people like Maeda offered up.

Men clad in suits may have lined Parisian streets and filled Parisian theaters to catch a mixed-fighting fad as it swept across the continent. Big crowds may have reveled in watching the world’s best fighters across any style make front-page news as far away as Hawaii and Australia. But there were periods in which these types of clashes fell out of favor, and by 1963 boxing was the combat sport worth caring about in America. Wrestling and grappling, for all its rich history, had fallen on harder times after scandals trivialized it. Proven lessons were largely forgotten by the public, and wrestling became the thing people didn’t talk about.

That was soon to change.

Thirteen years before Ali stepped in the ring to fight Inoki, a generation ahead of Art Jimmerson’s contest with Royce Gracie at UFC 1, and nearly five decades before James Toney and Randy Couture tangled in the Octagon, the first boxer-grappler showdown broadcast live on American television—LeBell vs. Savage—represented a key moment in the large arc of these events.

At first LeBell angled for the fight to take place in Los Angeles, where for almost forty years his notoriously tough mother, Aileen Eaton, promoted many of the biggest boxing and pro wrestling events on the West Coast at the Olympic Auditorium. Eaton thrived in the promotion business, but she never had the opportunity to promote a mixed-rules bout because the California State Athletic Commission wasn’t granted the authority to regulate this kind of handto-hand combat until 2006. The commission classified the boxer-grappler contest as an outlawed duel, so the fighters headed instead to Beck’s backyard, Salt Lake City, Utah, which placed no restrictions on that sort of thing. Agreeing to five three-minute rounds, the bout was a jacket match, meaning LeBell would wear his judo uniform and the boxer was required to wear a gi top with a belt, and, if he preferred, boxing trunks, boxing shoes, and light speed-bag gloves. The winner would be determined when a fighter was counted out for ten seconds or incapacitated, and the referee was the sole judge of that.

When LeBell arrived in Utah, he was surprised to learn that instead of facing Beck under these circumstances, Milo Savage would stand opposite him on fight night. LeBell was familiar with the former middleweight contender, having seen Savage box in person once at the Legion Auditorium in Hollywood, Calif. After taking his first twenty-five fights in the Pacific Northwest, Savage headed down the coast with a record of fifteen wins, six losses, and four draws. From October 1947 to February 1949, fourteen of Savage’s next fifteen bouts occurred in Los Angeles, and throughout his twenty-five-year career he made twenty-nine appearances in the City of Angels. As of the mid-1950s, Savage had matured into a ranked fighter and LeBell was experiencing the peak of his athletic career, earning the reputation of America’s best judoka following consecutive Amateur Athletic Union National Judo Championships titles in 1954 and 1955.

The night before the spectacle in Salt Lake City, LeBell, then thirty-one, made an appearance on local television. The host, whom LeBell felt was pro-Savage, implied that chokes don’t work and followed up with a grand mistake when he uttered, “show me.” LeBell snatched him, choked him out, and dropped him on his head. The newsman didn’t even receive a patch. “Judo” Gene picked up the microphone and offered a rant that his pro wrestling buddies back in L.A. would have been proud of. “Our commentator went to sleep,” he said. “I guess he’s quitting. Now it’s the Gene LeBell Show.” LeBell peered into the camera and promised to do the same to the thirty-nine-year-old Savage, now a crafty journeyman prone to trick punches and clowning around in the ring. “Come to the arena tomorrow night and watch me annihilate, mutilate, and assassinate your local hero because one martial artist can beat any ten boxers.” The exotic nature of the contest combined with LeBell’s antics, honed around grand characters in the combat sports worlds, produced a buzzed standing-room-only pro-boxing crowd of around 1,500 at the Fairgrounds Coliseum on a chilly Monday night, December 2, 1963.

Inside LeBell’s locker room, final rules were hammered out for the five-round contest. Savage’s people agreed to let LeBell grapple as he pleased, but he couldn’t strike at all. To confirm what he could or couldn’t do, LeBell pulled out a picture-heavy instructional book he penned that sold for $3.95 via mail order in Black Belt magazine.

“Can I pick him up over my head like this?” he wondered, pointing to a photo in The Handbook of Judo. Savage’s handlers were amused. “Can I choke him?” asked LeBell, placing his hands over his throat in “a comical way.” An L.A.-based lawyer who travelled with LeBell to Utah, Dewey Lawes Falcone, told him to quit screwing around. But “Judo” Gene couldn’t help himself. He was always the type to push buttons. “They’re laughing,” he remembered. “They’re just all happy that he’s going to knock me out.”

LeBell was familiar with the reaction. In Amarillo, Tex., where he wrestled professionally and took mixed-style fights for cash, most of LeBell’s challengers came from a nearby army base or the cow town’s dusty bar crowd. Locals received $100. Out-of-towners, $50. They, too, felt good about their chances. Then LeBell’s sadistic reality set in as he racked up ring time, an experience that lent him confidence ahead of the match in Salt Lake City.

Prohibited from striking, LeBell had to figure out how to navigate his way past Savage’s strikes to get inside and clinch. To make matters more difficult, Savage wore a gi top designed for karate, which meant it was constructed of lighter material than the judo uniform and more difficult to grip. And it was slathered in Vaseline, according to LeBell. The grappler’s plan to induce Savage to come at him was only reinforced after LeBell felt the boxer’s power as a punch to the stomach snapped the judo man’s obi—the black belt that tied together his kimono. “I towed broken down motorcycles with them. I’ve never had ’em stretch or break on me, but when this guy hit me it broke right in half,” LeBell said. “This guy hit pretty hard. You could do it a thousand times, I don’t think it would happen again. He just hit me right.” LeBell alleged that underneath Savage’s thin gloves he wore metal plates. Arms in tight, Savage was tentative to attack with anything but distance-controlling jabs, and LeBell, willing but unable to trade strikes, bided his time.

Inevitably LeBell found what he was looking for and locked up in a clinch—a result-defining position in any unarmed combat scenario. A modern boxer clinches to avoid getting hit, and referees are tasked to break up fighters, make them take three steps back, and hope they come out swinging. Wrestling is based very simply on tying up an opponent on the inside. Invariably the clinch favors anyone who knows how to grapple, which most successful boxers did quite well before the Marquess of Queensberry rules superseded London Prize Ring rules in 1867, essentially removing wrestling as part of the skill set required to win bouts. No longer did boxers need to know how to grapple above the waist and throw opponents to the floor. Clinching and holding remained relevant, mostly as a defensive mechanism, but the ability to grapple for takedowns, a benefit of going at it bare-knuckle, was engineered out of the sport.

When Jack Johnson operated atop the boxing heap, his clinch game was derived from the grappling techniques of wrestlers like William Muldoon, a famous athlete and fitness nut tasked with whipping into shape the last London Prize Ring rules champion, party boy John L. Sullivan. Part of the straight-laced Muldoon’s regimen for Sullivan was wrestling. Between competition and sparring, boxers seemed to get the message. Corbett, who supplanted Sullivan as the sport transitioned to a gloved affair, said as much when asked by a reader of his syndicated column.

“Ninety-nine times out of one hundred the wrestler would win,” Corbett wrote in 1919. “About the only chance for victory the fighter would have would be to shoot over a knockout punch before the echo of the first gong handled away. If it landed, he would win. But if he missed, he’d be gone. And every ring fan knows that the scoring of a one-punch knockout is almost a miracle achievement in pugilism. Years ago Bob Fitzsimmons attempted to battle the debate. Fitz was a powerful man, almost a Hercules. His strength was prodigious. And Fitz knew quite a bit about wrestling—and how to avoid holds and how to break them. So he scoffed when someone remarked that in a contest between a wrestler and a boxer that the former would win.”

Ernest Roeber, a European and American Greco-Roman heavyweight champion, ended up stretching Fitzsimmons straight.

Rules defining boxing became hyperfocused on one aspect of the discipline—molding the acts of punching and defending punching into the “sweet science.” Boxers still use clinch skills traceable to the days of London prizefighting, though so degraded is the notion of boxers maintaining meaningful clinch games, that a modern-day question persists about whether Ronda Rousey would throw Floyd Mayweather Jr.—the best boxer of his time and a stone heavier than the female judoka—on his head in a real confrontation. By the early 1960s, boxers hadn’t needed to earnestly practice holds in the clinch for nearly a century. Those tricks managed to survive through grappling-based systems, like judo and catch-as-catch-can, which LeBell practiced at a masterful level.

During the fourth round, despite aggravating an old shoulder injury earlier in the fight when Savage awkwardly shucked him off in the clinch, LeBell set up for the kill. “Judo” Gene dropped his left arm, baited Savage to throw a right cross, deftly maneuvered underneath the punch, and tossed his opponent to canvas. LeBell clung to the boxer’s back and Savage, unaware of what else to do, grabbed a thumb to sink his teeth into it. LeBell threatened Savage. If the boxer bit him, LeBell promised, Savage would lose an eye. That’s when a rear-naked choke was set and LeBell made good on his promise from the television broadcast the night before. The referee, a local doctor, didn’t know how to react when LeBell strangled Savage unconscious. He hadn’t worked a fight that included impeding blood circulation to the brain as an option. Media reports indicated the boxer was out cold for almost twenty minutes, an absurd length that these days would require at least a siren-filled ride to the hospital.

Adding insult to injury, LeBell “accidentally” stepped on Savage’s chest as he walked away. He winked. This incensed a riled-up crowd, already uncomfortable with the idea that boxing was bested by an Asian martial art. Well before Savage came to his senses, the Salt Lake City crowd grew spiteful. Chairs and cushions flew. A fan attempted to stab LeBell after he stepped out of the ring. The martial artist half-parried the attack and moved past his assailant, but he got stuck nevertheless. “I kept on going but it went through me,” LeBell said. “It was pretty big.” Still, the judo man survived, won the day, and martial artists rejoiced.

With LeBell assigned as the referee, and Ali facing Inoki, the martial arts community reacted in 1976 as if a great opportunity to score another big win over boxing was theirs for the taking. “The way it was billed, we were so excited,” said William Viola Sr., a martial artist out of Pittsburgh, who bought all-in on the attraction. “The catch wrestler, Inoki, would actually be able to use all his skills. Ali was the boxer and he’d box. The buildup was unbelievable.”

Unlike all-time great Jack Dempsey, Ali actually agreed to take on a mixed-style test. He wanted it and so did Inoki, and in the end their rules weren’t so different than what Dempsey and Lewis floated to the public during the 1920s. Ali laid down and Inoki accepted a challenge to determine the best fighter in the world. Yet many English-speaking boxing scribes maligned the heavyweight champion for participating in a “farce”—otherwise known as something great boxers have always been connected with.