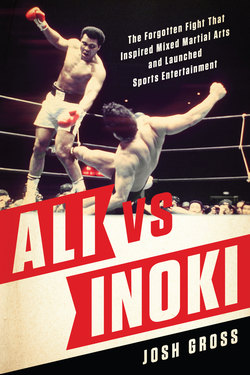

Читать книгу Ali vs. Inoki - Josh Gross - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеROUND THREE

Marcus Griffin, in 1937, authored an apparent attempt to uncover the world of professional wrestling. Whether Griffin acted as a reporter or a flack is up for debate, as are reported events strewn throughout the pages of his book, Fall Guys: The Barnums of Bounce—The Inside Story of the Wrestling Business, America’s Most Profitable and Best Organized Professional Sport. Sorting fact from fiction in the wrestling world did not come easy then, and it still doesn’t. Wrestling is as underhanded and shifty a business as there ever was. Indisputable, however, is that Fall Guys exposed the wrestling world to the public in a way it hadn’t been before, and that Griffin earned full credit for coining the “Gold Dust Trio.”

No one uttered that term prior to Griffin’s work being published, but everyone in the pro wrestling world remembered it afterwards. The group nickname stuck because in many ways the Gold Dust Trio bridged pro wrestling’s lingering competitive nerve, the roots of catch-as-catch-can, to part-of-an-angle exhibitions indicative of WWE’s product in 2016.

“Strangler” Lewis, Billy Sandow, and one of the smartest pro wrestling people that ever lived, Joe “Toots” Mondt— whom Griffin, a newspaperman, was rumored to be on the payroll of from 1933 to 1937, and whose interviews were used as Fall Guys’ main source—changed pro wrestling. Mondt’s shift in ring philosophy and practice, Sandow’s approach to consolidating wrestlers under exclusive contracts, and Lewis’ star power, when combined, were that meaningful.

Mondt, a young wrestler, booked matches, plotted storylines, and envisioned an open style that blended elements of combat sports without the trouble of sport—an impediment, from time to time, to exciting wrestling action. Body slams and suplexes were mixed in with fisticuffs and grappling, laying the framework for a charged-up, vaudevilleinspired creation: “Slam Bang Western-Style Wrestling.” This wasn’t dumb luck. Even in his youth, Mondt possessed a wealth of knowledge regarding many forms of competitive combat sports.

Compared to wrestling during the previous decade, when crowds sat through hours-long grappling matches, Mondt’s creation was a huge hit with fans, in part because of the finishes he engineered. More than a revamping of the style of wrestling, Mondt, Sandow, and Lewis established a troupe of wrestlers who traveled like the circuses Mondt worked as a teenager, where he crossed paths with the man who taught him how to wrestle, fellow Iowan Martin “Farmer” Burns.

It took some research, according to Griffin’s account, before Mondt unearthed the story of James Figg, through which he explained to Sandow and Lewis what he wanted to accomplish. Figg, a fistic nonconformist whom Jack Dempsey called the father of modern boxing, was one of the first cross-trained fighters. During the second decade of the eighteenth century, the Briton was considered the best prizefighter on the planet. He could box a wrestler. Grapple a boxer. He could fight in the clinch. This was the basis for “Figg’s Fighting,” a style that became well-known throughout the British Isles as his reputation grew.

Sandow and Lewis saw the light, and within a few months the wrestling gates grew as members of the establishment, four promoters in the Northeast known as “The Trust,” quickly felt the pinch of hard competition.

Even before being publicly rebuffed by Dempsey, “Strangler” Lewis, the man most Americans accepted as the best heavyweight wrestler at the time, toured the country as the tip of the Gold Dust spear. The best wrestlers, like Lewis, actually knew what they were doing, and sometimes painfully implemented their knowledge against other presumably tough men. Up until the 1920s, the hierarchy of wrestling was based around whoever was perceived to be the best shooter and hooker, because if push came to shove, the guy who knew best how to push and shove was going to walk away with the belt. Choreographed outcomes, which became standard operating procedure as the Gold Dust Trio’s influence grew, needed two willing participants. If the guy tabbed to drop the belt didn’t follow the plan, or if wrestlers went off script, a price needed to be paid.

Mondt, a legitimate hooker, was brought into Lewis’ camp based on the Farmer’s recommendation in 1919. The pair sparred and worked out, leaving Lewis to feel that when he needed a “copper,” a pro wrestling euphemism for “enforcer,” Mondt along with tough guys Stanislaus Zbyszko and “Tiger Man” John Pesek could ably handle the job.

Pesek preferred wrestling for sport over show, but was vicious in defense of the Gold Dust Trio when required. After a match on November 14, 1921, at Madison Square Garden, Pesek and his manager Larney Lichtenstein of Chicago had their licenses revoked by the New York State Athletic Commission, then chaired by William Muldoon. Pesek mauled a reputed “trustbuster,” Marin Plestina, who was known for spotty cooperation when it came to laying down to promotions and their champions. Pesek butted and gouged Plestina in his eyes before being disqualified. The big Serbian was laid up in his room at the Hotel Lenox for several days nursing an abrasion of the cornea, and Pesek never wrestled in New York again.

Pesek and many of the wrestlers under contract to Sandow came and went, yet finding a place to work during this time wasn’t a problem. If the consolidation of talent was troublesome for anyone, it was promoters used to doing business with their controlling interests and mechanisms in place. As the trio cobbled together a set of wrestlers, booked venues, and promoted across the country, the “Strangler” Lewis business grew strong—though not so much the industry as a whole. Lewis held on to the title that mattered, except when it suited the business not to, and since fans might grow weary of the same man as reigning champion month after month, year after year, it sometimes made sense for him to drop the belt. Everything was predetermined, mostly due to Mondt’s handiwork. Groups of promoters got the message, and because fans passed through turnstiles to watch, this new brand of wrestling was widely adopted. Even with Mondt dictating matches and outcomes, and Sandow controlling talent, the trio wouldn’t easily own a field that had been crafted by some of the hardest men of the last hundred years. This is the stock folks like Joe Stecher came from. Stecher, a pig farmer who subdued his animals like many of the men he beat, by scissoring them between his legs, was every bit as dangerous as “Strangler” Lewis, and had the backing of entrenched powers the trio sought to overtake.

“Strangler” and Stecher famously wrestled to a fivehour draw during a shoot match in Omaha, Neb., on July 4, 1916. The bout, with Stecher the titleholder, drew great criticism from press who covered the slow, uneventful contest. These were the types of matches Mondt wanted to rid wrestling of, though that would not come without its share of unintended consequences. Mondt wanted the wrestlers to work less, so he established time limits. Extended grappling sessions were all but removed. For the most part, wrestling manifested into pantomime fighting.

Until Griffin’s book, most fans and media operated as if the matches were legitimate when for years they weren’t. Anyone who said otherwise broke “kayfabe,” wrestlespeak for the portrayal of what was real or true, and hookers had an easy remedy for that. Joints were always there for twisting. Arteries always good for pinching. But pro wrestling was shifting from showcasing athletes well versed in the foundation of the game—the damaging catch-as-catch-can stylings of pioneers Lewis, Gotch, and Burns—to those playing off showmanship and characters who could create “heat” with the audience.

A couple days before Muhammad Ali—technically he was Cassius Clay, and remained so until 1964—made his first ring appearance in Las Vegas, a ten-round decision over Duke Sabedong, the nineteen-year-old from Louisville, Ky., reformatted his mind as to how he wanted people reacting to him.

During a live radio interview to promote Ali’s seventh fight, the boxer, sitting beside beloved matchmaker Mel Greb, responded somewhat meekly about himself, considering the reputation he went on to earn. A year removed from winning a gold medal in Rome, Ali was joined in studio by iconic pro wrestler “Gorgeous” George Wagner, a champion at talking, annoying people, and creating headlines, but not much else as it pertained to wrestling. Thankfully for George, he was in a profession that rewarded such abilities.

The night before Ali took to the Convention Center on June 26, 1961, against Sabedong, a six-foot-six Hawaiian, George faced Freddie Blassie in the same building. George and Blassie were two of the best-known wrestlers working out of the Los Angeles territory at the time. Much had changed about pro wrestling since the Gold Dust Trio days, and while Blassie could handle himself some, George was the sort of wrestler who would have been tied in knots had “Strangler” Lewis or Joe Stecher placed their hands on him. “Gorgeous” George represented a consequence of pro wrestling’s push to campiness, a true departure from the submission wrestling techniques born out of Greece and Japan and countless corners of the world, to a showy mindless form of entertainment that fills the gap between television commercials. George was primarily a character pushed to the top of cards based on his charisma and drawing power. After pro wrestling prioritized selling and showmanship over honest-to-goodness skills, the conditions were set for wrestlers like George to emerge.

Well past the peak of George’s career—when the TV boom during the late 1940s demanded content to draw in viewers, all three networks featured pro wrestling on their airwaves, and business received a surprising boost that jolted it out of a considerable lull— the 220-pound “Human Orchid” still made the most out of getting people to hate him. George was a drunk by the summer of 1961. His liver was shot, and he was two Christmases from dying, broke, of a heart attack. It was coincidence or fate that Mel Greb put the wrestler in the same room with the fresh-faced, smooth-skinned African American Ali.

“I’ll kill him; I’ll tear his arm off,” George ranted about his opponent, the classic Freddie Blassie. “If this bum beats me, I’ll crawl across the ring and cut off my hair, but it’s not gonna happen because I’m the greatest wrestler in the world.”

Ali absorbed what was in front of him and considered how much he wanted to see “Gorgeous” George in action. No matter what happened, the boxer felt as if something unmissable was about to go down and he needed to watch a man who proclaimed he’d win because he was the prettier wrestler.

“That’s when I decided I’d never been shy about talking,” the boxer said to historian Thomas Hauser in the biography Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times. “But if I talked even more, there was no telling how much money people would pay to see me.”

Ali was simply playing off his strengths. He was already a poet, creating and reciting lines about his favorite boxers and moments, so it wasn’t as if George inspired him to make rhymes. More to the point, this was brashness recognizing itself in an unadulterated, propped-up form. Ali loved the show business side of pro wrestling, and George woke him up to what was possible.

It was a full house for George and Blassie, about double what Ali and Sabedong managed to produce the following night. Angelo Dundee’s charge watched the man that captivated him go through his usual shtick. George stepped into the ring on a cutout of a red carpet. “Pomp and Circumstance” played over loudspeakers. He tossed out gold-colored bobby pins that were removed from his hair to a hissing, snarling crowd. “Georgie pins,” the 14-karat version, were reserved for friends and well-wishers willing to swear an oath never to confuse regular bobby pins for these. The wrestler’s personal valet, whether lady or gentleman, used a super-sized sterling silver atomizer to douse his corner, the referee, the crowd, and, sometimes, his opponent in the sweet-smelling “Chanel No. 10,” a concoction that existed only in the fanciful world of “Gorgeous” George. His marcelled platinum locks, courtesy of Hollywood’s famous Frank & Joseph Hair Salon, were perfectly suited for the lacy, frilly gowns and sequined satin robes he wore into the ring.

“I don’t really think I’m gorgeous,” the wrestler, a natural brunette, was known to say. “But what’s my opinion against millions?” Once he stepped between the ropes and prepared to put on a show, he delighted in slowly folding his robes, reportedly valued at as much as $2,000 apiece. The slower the fold, he discovered, the more the crowd despised him. Against Blassie, George wore a form-fitting red velvet one. He was absurd, but that was the point. More than a third of his fans were women, and on plenty of occasions George dealt with the threat of having a purse hurled at him. Men were known to stick lit cigars into his calves. They hated him but they watched, especially in Los Angeles, where the Olympic Auditorium was home for “G.G.”

“When he got to the ring, everyone booed,” Muhammad Ali would later tell Dundee, according to John Capouya in his book Gorgeous George: The Outrageous Bad-Boy Wrestler Who Created American Pop Culture. “I looked around and I saw everybody was mad. I was mad! I saw 15,000 people coming to see this man get beat, and his talking did it. And I said, ‘This is a gooood idea.’”

Ali needed no gimmicks to attract or repel people. He was a magnet, always; it just depended on the other side’s polarity. The public’s feelings about the boxer throughout his career were based on tangible things: cockiness born from self-belief and success in real competition; a conversion to Islam; unconventional political views; changing his identity from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali; challenging the U.S. government as a conscientious objector during the war in Vietnam; civil rights activism; and dozens of other important stances he took throughout his career. Ali changed the way fighters approached publicity. Unafraid to consider consequences in the ring and out, Ali spoke like no boxer before him, offering statements on serious topics or clownish things as he wished. The man was much more than a lug, but when he incorporated an over-the-top feel to his language, when he harangued opponents for being ugly or looking like a bear or, in Inoki’s case, a pelican, or when he began bragging about himself, which he hadn’t done much until pro wrestlers changed his perspective, people simply ate it up.

When George Wagner bumped into Ali in Las Vegas, the bright lights had long dimmed on the wrestler’s career. Following promotional wars and match-fixing scandals that emerged out of pro wrestling’s turbulent 1930s, George’s buffoonery was the sort of thing no one watching could be confused about, and the total lack of a sporting attitude actually helped propel him to prominence and rekindled a new kind of interest in pro wrestling in America. Pro wrestling needed to be fake and not many of the boys were less real than “Gorgeous” George.

In a Las Vegas locker room following the “no contest” with Blassie, Greb brought Ali to see George, whose advice served the boxer well. “You got your good looks, a great body, and a lot of people will pay to see somebody shut your big mouth,” George is quoted as saying in Capouya’s book. “So keep on bragging, keep on sassing, and always be outrageous.”

That ability put George in the main event of the first pro wrestling show at Madison Square Garden since a twelveyear ban in New York that was inspired by a historic double cross. The Gold Dust Trio fell apart in 1929 after Mondt walked away following a dispute over control with Billy Sandow’s brother. Mondt learned much about the business and carried on as a major player through the rest of his days. Wrestling, meanwhile, became fragmented, and the lack of a true national champion against an emerging reality of various regional championships confused the public and elicited criticism from the press. One of these champions was Danno O’Mahoney, a showman with little shooting gravitas who operated at the mercy of bookers and hookers. He just couldn’t protect himself, so it seemed everyone tried to snatch the belt from him no matter what any script said.

A wrestler named Dick Shikat took his chance at O’Mahoney, and while some of the sport’s most powerful promoters were aware of what might happen, it was primarily the challenger’s call once they stepped in the ring. Shikat hooked the fish in less than twenty minutes, and all hell broke loose. Burned promoters played games, booking Shikat unbeknownst to him in numerous states until he was barred by many commissions for being a no-show. This prompted a trial in Columbus, Ohio, at which all the major promoters were forced to testify. The lid was blown off wrestling: whatever credibility the business had as a sports venture was gone so far as the public was concerned; the media covered it less and less until it didn’t at all, and a multimillion-dollar national spectacle devolved into a regional program that allowed basically everyone to claim they were a pro wrestling world champion.

Fifteen of these so-called champions existed when George appeared at Madison Square Garden in 1949. He was not among them at the time, though even he held a title once. Two days after George appeared at the Garden on February 22 of that year, the New York Times’ Arthur Daley led his column, “Sports of the Times,” with this: “If Gorgeous George has not killed wrestling in New York for good and for all, the sport (if you pardon the expression) is hardy enough to survive a direct hit by an atomic bomb.” Less than five years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that was quite a statement. Daley was wrong both ways. George wouldn’t kill pro wrestling in New York or anywhere else, and the business wasn’t impenetrable, though, like the proverbial cockroach in a nuclear explosion, it’s a reputed survivor. Despite the weeping of newspaper writers, George’s peak through the mid-1950s brought him much fame and money. As gimmicks go, yes, George’s panache went stale, yet it was captivating enough even at the tawdry end to rope in someone like Ali.