Читать книгу A Race So Different - Joshua Chambers-Letson - Страница 10

Оглавление1 / “That May Be Japanese Law, but Not in My Country”: Madame Butterfly and the Problem of Law

Tuan Anh Nguyen spent most of his life in the United States. He was born in Vietnam to a US American father and Vietnamese mother in September 1969. His mother abandoned Nguyen and his civilian contractor father, Joseph Boulais, when he was only a few years old. In 1975, Boulais returned to the United States with his six-year-old son, whom he continued to raise. At the age of twenty-two, Nguyen pleaded guilty to two counts of sexual assault on a minor in a Texas state court. A few years later in 1996, while serving out the terms of his eight-year sentence, Congress passed the Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRAIRA). IIRAIRA mandates the deportation of aliens convicted of a felony charge. As a result, the Immigration and Naturalization Service initiated deportation proceedings against Nguyen, and an immigration judge subsequently ordered his deportation to Vietnam. Despite having a citizen father and being raised by this father in the United States, the US government considered him to be an alien and targeted him for deportation to a place he hardly knew.

Nguyen’s legal status was written nearly thirty years before his birth, at the height of the Korean War and the US military’s occupation of Japan. In 1952, Congress passed the McCarran-Walter Act, heavily revising the section of the US code that regulates immigration and naturalization. As part of the act, the legislature clarified citizenship eligibility for children born abroad to unwed parents when only one parent is a US citizen. While children born to citizen mothers automatically receive citizenship retroactive to birth, children born to citizen fathers must meet three additional requirements for citizenship eligibility. Nguyen appealed his case, arguing that the differential burden violated both fathers’ and sons’ equal protection rights. (Unaware of the differential burden, Boulais had not registered his son as a citizen within the statute of limitations.) Justice Anthony Kennedy’s Supreme Court opinion in Nguyen v. INS affirmed the constitutionality of the law, counterintuitively arguing that the three-part bar—despite the fact that it made it three times easier for fathers (often US servicemen) to escape responsibility for illegitimate children born overseas—forwarded a legitimate government interest in the “facilitation of a relationship between parent [father] and child.”1

In a 2009 New York Times interview, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (who was among the dissenting Justices) described Nguyen (and a similar case, Miller v. Albright) in terms that directly associated it with the legacy of US imperialism in Asia. In a surprise move, she did so by suggesting that the majority’s ruling was written under the sign of a popular Orientalist opera: “They [the majority] were held back by a way of looking at the world in which a man who wasn’t married simply was not responsible. There must have been so many repetitions of Madame Butterfly in World War II. And for Justice [John Paul] Stevens [who voted in the majority in Nguyen and penned the Miller opinion] that was part of his experience.”2 Ginsburg’s interview implies that the impact of Madame Butterfly extends beyond the proscenium arch, insinuating itself into the high court’s interpretation of the law. At the same time, she evidences the ways in which Western audiences regularly mistake the fiction of Madame Butterfly for a reality. As if the opera were a template for actually occurring incidents, she muses, “there must have been so many repetitions of Madame Butterfly.” Somewhere in the middle of Nguyen and Madame Butterfly, the difference between a legal reality and an onstage theatrical spectacle collapses.

In 1907, Giacomo Puccini premiered Madama Butterfly at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City.3 It is a tragic story of a Japanese bride in nineteenth-century Japan who is married to and ultimately abandoned by her US American husband, ending in the young bride’s suicide. Since its debut, Madama Butterfly has become a centerpiece of most major opera companies’ repertories, and by some accounts it is one of the most produced operas in the world. Due to its iconic and canonical status, Madama Butterfly has contributed significantly to the shaping of cultural stereotypes of Asian difference and Asian femininity. As such, the Butterfly narrative is a central critical object for the field of Asian American studies.4 But how is it that Madame Butterfly has come to influence the writing of American law, and in what surprising ways does the narrative itself function as a vessel for the transmission of knowledge produced about Asian racial difference in US law?

This chapter argues that the legal management of Asian and Asian American difference is not simply the historical background against which the various versions of Madame Butterfly were written but that the Butterfly narratives themselves function as agents for the law’s codification and transmission. Madame Butterfly is a product, manifestation, and ultimately a representative of exclusion-era jurisprudence; it is part of the dominant culture’s juridical unconscious. This term is a legally focused amendment to Fredric Jameson’s description of literature as part of the “political unconscious,” whereby “master narratives have inscribed themselves in the texts as well as in our thinking about them; such allegorical narrative signifieds are a persistent dimension of literary and cultural texts precisely because they reflect a fundamental dimension of our collective thinking and our collective fantasies about history and reality.”5 As I will demonstrate, the Butterfly narrative neatly aligns with exclusion-era jurisprudence in areas of the law ranging from the immigration code to courtroom procedure and child custody. As a work of popular entertainment, it codified and represented these narratives, giving them the verisimilitude of flesh-and-blood presence onstage while confirming and embedding them within the national culture. Furthermore, as Ginsburg’s comment suggests, Madame Butterfly’s legal force is not contained in the twentieth century. Due to its continued popularity, it still functions as part of the nation’s juridical unconscious. It acts as a medium for the continued transmission of exclusion-era ideas about Asian racial difference, projecting these ideas onto the contemporary Asian American body.

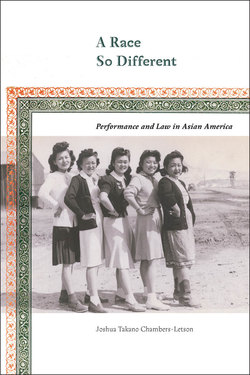

Figure 1.1. Geraldine Farrar in the 1907 Metropolitan Opera premiere of Madama Butterfly. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Opera Archives.

Before continuing, I need to make one key point about my intervention into critical analyses of the Butterfly narrative. In the compendium of critical work published about the narrative, few scholars have critically interrogated the role of law in Madame Butterfly. But the law is everywhere in the heroine’s tale, including lengthy discussions of the marriage contract that binds Cho-Cho-San to her US American husband, legal counsel provided by her friends after she is abandoned, and a stunning scene in which the heroine imagines herself performing before a judge in a US court. Important Asian Americanist analyses of the narrative have often overlooked the legal theme in their studies of the Orientalist configurations of gender and the spectacle of US empire in the Butterfly narrative. While some of the studies have focused on the opera, many more have turned to works inspired by the opera, including two seminal works that premiered in 1989: David Henry Hwang’s Broadway play M. Butterfly and Claude Michel-Schönberg and Alain Boublil’s musical Miss Saigon.6 Much less attention has been paid to the two texts on which the opera is based, John Luther Long’s 1898 novella and Long and David Belasco’s successful Broadway adaptation of this work in 1900.7 The three original versions of Madame Butterfly were, like their descendants, popular and commercial successes, but few contemporary studies offer a comparative analysis of all three. If one looks at each version individually, the law seems simply to be an otherwise random incident of plot, which might account for the literature’s critical oversight of this factor. However, when the versions are read comparatively, it becomes clear that the law is a consistent concern that is central to and survives every early iteration of the story.

A focus on the problem of law in Madame Butterfly is necessary insofar as it supplements a missing piece of the Butterfly puzzle. My interest in the problem of law does not offer an alternative to critical investigations of race, gender, and empire in Madame Butterfly so much as it builds on this body of scholarship in order to offer a robust example of the ways in which these phenomena are produced at the intersection of law and performance in the narrative. It should be observed that one of the notable exceptions to the paucity of scholarship about law and Madame Butterfly is an article written by family law scholar Rebecca Bailey-Harris. Bailey-Harris’s 1991 article is a study of the “conflict of laws” posed by Madame Butterfly and analyzes the recently codified Meiji reforms of 1898 in Japan in relation to US jurisprudence of the same time.8 While the author provides a precise accounting for each and every legal question that Madame Butterfly raises regarding both US and Japanese law, her approach is avowedly guided by a mechanistic attention to the “issues of concern to a lawyer in the audience [that] arise from the plot.” Bailey-Harris goes so far as to ask whether the heroine would have been “better advised to refrain from so drastic a step [her suicide]” given the likelihood that both the United States and Japan would have recognized her marriage.9 Like Ginsburg, Bailey-Harris treats Madame Butterfly as if it were a possible historical reality, exhibiting little critical interest in the fact that the heroine is a fictional construct structured by bourgeois, racist, sexist, and imperialist aesthetic conventions. As an alternative, I offer a close reading of the problem of law in Madame Butterfly, one that attends to both the questions of law and aesthetics, in order to demonstrate the legal function of an aesthetic performance which works alongside the law to transmit and codify Orientalist notions about gendered, racial difference for Asians and Asian Americans.

This chapter is divided into three parts. After mapping out the cultural significance and the historical development of the three versions of Madame Butterfly, I trace the alignment between Long’s novella and Asian-exclusion legal discourse. Part 2 expands this analysis to focus on the legal theme within Madame Butterfly as it reflects Asian American jurisprudence in the late nineteenth century. Part 3 brings us into the present with a focus on Trouble, the mixed-race progeny of Pinkerton and Cho-Cho-San’s love affair. I thus conclude with an assessment of the ways in which this mixed Asian figure becomes manifest as a problem for contemporary law and culture.

Prologue: A Brief History of the Three Butterflies

It is little coincidence that the publication and dissemination of the various versions of Madame Butterfly occurred during a period of increased anxiety about the threats posed to national and racial borders by Asian bodies flowing in and out of the sphere of the US empire. Long’s novella was published in 1898, sixteen years after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act and the same year that the United States officially began both the colonization of the Philippines and the illegal annexation of Hawai‘i. At the end of the nineteenth century, US border definition was threatened by the empire’s territorial expansion outward and the need to draw foreign bodies inward in order to satiate the needs of expanding capital.10 Legal and cultural apparatuses thus began to mark Asians as the exception to national, legal, and cultural forms of theatrical as a means of managing and containing the crisis that they posed to the constitution of ideal borders and national subjects. As a representative of the dominant culture’s juridical unconscious, Madame Butterfly exemplifies Lucy Mae San Pablo Burns’s assertion that US American popular culture is “part of the ideological state apparatus that extend[s] U.S. cultural hegemony” and empire.11 It manifests and embodies the racial ideology of the dominant culture through aesthetic means.

The short synopsis of all three narratives is this: a US officer, Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton, is stationed in Nagasaki, Japan. Beset by boredom, he takes a fourteen-year-old Japanese wife—Cho-Cho-San (or Cio-Cio-San in the opera). Eventually Pinkerton abandons his Japanese child-bride, who remains steadfast in the belief that he will return. In his absence, she raises their son, curiously named Trouble. Importantly, Trouble was born after Pinkerton’s departure and without his knowledge. Pinkerton’s friend Sharpless, a US consular officer, remains concerned for the young woman and her son and attempts to convince the girl to remarry. She declines, believing that her marriage is protected by the laws governing marriage in the United States and that she will be able to press her case in a US court, if necessary. Pinkerton eventually returns from the states but—to Cho-Cho-San’s great horror—with a white (US American) wife. As a result, Cho-Cho-San kills herself in the hopes that Pinkerton will claim and raise his son.

John Luther Long never set foot in Japan, and according to opera historian Arthur Groos, much of his narrative was pieced together from collaboration with Long’s elder sister, Jennie Correll. Correll lived in Nagasaki for a number of years as a missionary before returning to the United States in 1897.12 The centrality of the question of law in the three versions of Madame Butterfly may have been an accident of autobiography, as Long did not make his living as a novelist and dramatist but as a lawyer.13 The story first reached the upper- and middle-class audience of Century Magazine in January 1898. It proved so popular that the magazine published a reprint in book format and in 1903 released a “Japanese edition” with illustrations. The general excitement with which the story was received was, no doubt, aided by the fact that, as noted earlier, 1898 was a significant year in the history of US imperial expansion into the Pacific.

Audiences in the United States were hungry for exotic stories of the Far East, and shortly after the book’s publication, Long collaborated with theater impresario David Belasco to adapt the story into a one-act play. A one-act version of Madame Butterfly premiered at New York’s Herald Square Theater at 10:00 p.m. on May 5, 1900, with a production price of $4,000.14 The play’s literary merits are less impressive than its historical and cultural significance, and it was a success primarily because of Belasco’s trademark technological innovation. The production received rave reviews and wowed audiences with its incorporation of emergent visual technologies made possible by the shift from gas to electric lighting. Belasco fused novel design elements with extreme naturalist conventions to produce an air of authenticity, convincing audiences that they were seeing an accurate representation of Japan and Japanese femininity.

Belasco wanted to use the magic of the theater to transport audiences into an exotic and otherworldly Japan. Reviewers reveled in the technological sophistication of the show, beginning with the opening moment in which, according to one review, a “drop curtain arose, disclosing another curtain split in the middle and bearing typical Japanese figures.”15 This gave way to a series of lushly painted screens depicting scenes from Japanese country life, described in the New York Times thus: “Beautifully illuminated views of the land of cherry blossoms in the time of cherry blossoms are shown. The setting sun illuminates the dome peak of Fujisan. There is one lovely water view. Thus, gradually, one is taken to Cho-Cho-San’s dainty little cottage, which is a perfect picture in all its details.”16 The set was a stunning performance of what Belasco imagined a Japanese home to be: walls lined with shoji screens, murals covering the fixed internal walls, and rich light pouring in from all angles. Another reviewer wrote, “Its pictures of Japanese life and domestic customs, . . . its brilliant display of color, its changing light effects, combine to make it a show that will be much talked about and that many persons will want to see.”17 This assessment proved correct, and audiences flocked to the production.

One of the primary draws of the evening was the technological simulation of the passage of time in an extended scene in which Cho-Cho-San waits through the night for Pinkerton’s return. The success of this spectacle must have been at least somewhat compelling, as actress Blanche Bates held the audience rapt for no less than fourteen minutes as she sat perfectly still in absolute silence as lighting effects evoked the breaking dawn amid the sounds of singing birds.18 As columnist Alan Dale waxed, “Even if I forget the story of ‘Mme. Butterfly’ the picture of Cho-Cho-San standing at the window from evening till night and from night till morning will remain impressed upon my memory.”19 The success of the production resulted in the transfer of an expanded three-act version of the play to London’s West End a few months later.

In London, the narrative architecture of Long’s story was once more kept in place, and most of the expansions aimed to give the characters increased psychological heft or to give audiences more of the exciting design elements that made the production a hit in New York. It starred ingénue Evelyn Millard in the title role, whose appearance was greatly anticipated in the press and was featured in a cover story for the Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News.20 Opera composer Giacomo Puccini sat in one of the audiences of the London production and soon after attained Belasco’s permission to adapt the story/play into an opera. Madama Butterfly debuted to a mixed reception at La Scala on February 17, 1904, with a libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. After various revisions, a robust version returned to New York with a premiere at the Metropolitan Opera House on February 11, 1907, with famed soprano Geraldine Farrar in the title role.21 Again, the narrative remained fairly intact, with the majority of the adaptations made to accommodate Puccini’s lush Orientalist score. Shortly after this, Puccini completed revisions on what was to become the standard version of Madama Butterfly.

Madama Butterfly remains one of Puccini’s most popular operas in the United States and across the globe. Although my analysis of Belasco’s dramatization will reconstruct sections of the original one-act production that debuted in New York in 1900, my descriptions of the opera are drawn from the Met’s 2006 production, directed by the late Anthony Minghella. I turn to this particular production for a number of reasons. The production is part of the Metropolitan Opera’s recent mission to update its repertoires to draw in new audiences. This mission is based on the presupposition that classical operas, such as Madama Butterfly, maintain their cultural relevance and social importance in the twenty-first century. To promote the opera, the production was broadcast live in Times Square. It continues to be broadcast to movie theaters throughout the country and, indeed, the world. It is also available for purchase in DVD format or for viewing on the Met’s website for a small fee. If the argument can be made that Madama Butterfly is a relic of another era, I would suggest that the Met’s mediated promotion and hyperdistribution of Minghella’s production refutes this assumption. In other words, Butterfly has not left the building, and she does not show signs of doing so anytime soon.

Act I. “American Hardware”: Exclusion in Long’s House on Higashi Hill

As a manifestation of the United States’ juridical unconscious, one could say that Long’s 1898 novella is a text in which a US American lawyer imagines a Japanese woman imagining herself as she performs in response to US law. But even before Cho-Cho-San begins her fantasied journey into US jurisprudence, the domestic relations that structure her marriage to Pinkerton are neatly representative of dominant conceptions of US sovereignty in the early period of Pacific expansion. The novella begins with a domestic dispute about the exclusion of Cho-Cho-San’s family from Pinkerton’s home. This argument mirrors the legislative debates about Asian exclusion occurring in both federal and state legislatures and courtrooms at the turn of the century.

Figure 1.2. Metropolitan Opera premiere of Madama Butterfly, 1907. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Opera Archives.

In the opening sequence, Cho-Cho-San asks her new husband, Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton, to explain the hybrid construction of their home:

Some clever Japanese artisans then made the paper walls of the pretty house eye-proof, and, with their own adaptations of American hardware, the openings cunningly lockable. The rest was Japanese.

Madame Butterfly laughed, and asked him why he had gone to all that trouble—in Japan!22

This early sequence is significant of two concerns that run throughout the narrative: an attempt to define and demarcate the territory of US sovereignty beyond US borders, and the crisis of subject constitution posed by figures and spaces that exist between and across both the United States and Japan.

Pinkerton’s response to Cho-Cho-San’s question is instructive: “‘To keep out those who are out, and in those who are in,’ he replied, with an amorous threat in her direction.”23 I will return to the first half of his answer later, but here I want to emphasize his “amorous threat” as that which announces the sexual and imperial valences of the narrative. The locks on the house (with “openings cunningly lockable”) function as something of a chastity belt that locks Pinkerton’s sexual conquest away from the rest of the world. It simultaneously describes the US military’s adventures in the Eastern Hemisphere, with expansion into Asian-Pacific sovereignties and territories. This was exemplified by Commodore Matthew Perry’s 1853 expedition to Japan, when Perry forced the Tokogawa Shogunate into a trade agreement with the threat of a naval attack on Nagasaki. Michio Kitahara, working with concepts adopted from Erving Goffman, argues that Perry’s mission was explicitly staged as a performance: “Since the Japanese were not accustomed to deal[ing] with the Americans, the skillful presentation of ‘appearance,’ ‘manner,’ ‘setting,’ and ‘personal front’ by Perry’s squadron [allowed] the ‘performance team’ [to] manipulate the Japanese effectively, control their definition of the situation, and make them open the country.”24 It can hardly be incidental that Pinkerton is a naval officer stationed in this same city. Indeed, the imaginary figure of Cho-Cho-San reflects the concurrent feminization of Asian nations that were seen as rife for conquest and dominance by the masculine US military that is represented by Pinkerton.

Just as Pinkerton and Cho-Cho-San stand in for an aggressive US military and passive Japan, the “American hardware” on the Japanese doors can be seen to reflect the US assertion of extraterritorial jurisdiction, the practice of claiming US sovereignty within Asian countries. In the novella, this occurs by way of a link to domestic structures of normative heteropatriarchy. On the one hand, a struggle over the exclusion of Cho-Cho-San’s Japanese relatives (those “who are out”) is an opportunity for Pinkerton to assert the sovereign right of exclusion, while it is also a means for taking possession of his wife. As Teemu Ruskola observes, the US assertion of extraterritorial jurisdiction in Asia (and China specifically) fundamentally transformed previous notions of sovereignty as being contained within the nation-state because “in China, among other places, American law did not attach to US territory but to the bodies of American citizens—each one of them representing a floating island of American sovereignty.”25 Pinkerton and his home mirror practices of extraterritorial jurisdiction performed by the United States, whereby sovereignty is delinked from the geographic boundaries of the nation and attached to the traveling body of the US agent abroad. His assumption of a home “in Japan!” with “American hardware” and his quick exclusion of Cho-Cho-San’s Japanese relatives neatly reflects the US government’s imperial practices of extraterritorial jurisdiction and exclusion as a means of constructing the nation and national identity.26 The result is that the space of sovereign exercise, which is to say the territory of US legal and cultural independence and self-determination, is dominated by Pinkerton, while transforming Cho-Cho-San into a figure that exists inside the United States from outside its borders, cut off from Japan while inside Japanese territory. Properly speaking, she is neither a US American nor Japanese subject. As such, she emerges as a transnational figure that floats between and is denied a proper place in both.

In defining the term transnational, Aihwa Ong places emphasis on trans as that which “denotes both moving through space or across lines, as well as changing the nature of something.”27 The transnational body is not only in a state of flux as she moves between spaces; she carries the potential to “change the nature” of the spaces that she traverses. This highlights the fact that, as Ramón H. Rivera-Servera and Harvey Young argue, a border must be conceptualized “as simultaneously a geographical locale and a condition/form of movement.”28 The border is realized through performance as the body moves between, across, and in relation to its often-porous limits. The body in performance thus poses a threat to the border because, “when bodies walk, drive, sail, or fly, their movements blur the here and there, constantly reorganizing the spatial relations and negotiating the consequences (political, social, economic, cultural) of their crossings.”29 In order to manage this threat, immigration law choreographs the immigrant’s body, placing limits on her range of movement or even her ability to cross into the geographical territory of the nation. For the Asian subject in the United States, this took the form of an exceptional juridical regime that was developed to control the threat of her perceived dance across borders. Cho-Cho-San’s figuration in Long’s novella and the struggle over who, precisely, is excluded from Pinkerton’s home is significant of this fact.

After Pinkerton explains his reason for installing the locks, Cho-Cho-San happily performs the mantle of authority created by the decision to exclude. This performance is quickly disrupted, however, when she learns just who it is that her husband wants to keep out: “She was greatly pleased with it all, though, and went about jingling her new keys and her new authority like toys,—she had only one small maid to command,—until she learned that among others to be excluded were her own relatives.”30 Cho-Cho-San repeatedly petitions Pinkerton to allow for her relatives to enter the home. However, he dismisses the family as “a trifle wearisome” and definitively rejects her attempts to bring the outside in.31

It should be noted that while much of the early exclusion legislation specifically targeted the Chinese, these technologies were expanded to similarly exclude other immigrants. And while US legislators were worried that targeting Japanese immigrants would offend the Japanese government, thus resulting in largely administrative means for securing Japanese exclusion (such as the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907), there was a general domestic consensus that all Asian immigration was undesirable by the turn of the century.32 Reading a narrative about a Japanese character alongside Chinese exclusion law and jurisprudence can be a useful exercise insofar as it helps to clarify the ways in which the domestic dispute in Long’s novella functions as an “allegorical narrative” significant of the national and legal debates born from “collective thinking” and, more specifically, collective anxieties about Asians in America. Long’s readers would have been well aware of the general anti-Asian sentiment that pervaded the country. During the late 1870s and early 1880s, the nation was engaged in vigorous debates over what to do about a perceived influx of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Indian immigrants. As Shirley Hune argues, “the division within Congress and especially the conflict that took place between the legislative and executive branches over the Chinese issue centered largely over the means and not upon the goal of restriction itself.”33 With Asian immigrants figured as a threat to the national order, only a very small minority voiced support for a pluralist embrace of Chinese immigrants. Pinkerton’s desire to “keep out those who are out” would have resonated with popular sentiment about Asian subjects in general at the time.

Madame Butterfly was published nearly a decade after the US Supreme Court upheld Congress’s right to enact the first Chinese Exclusion Act.34 By the time that Long’s story hit the masses, it is likely that most readers would have been aware of the Court’s decision, Chae Chan Ping v. United States, which itself became something of a national drama. Indeed, media outlets turned to the rhetoric and narrative form of dramatic melodrama to report on the case, demonstrating the powerful role that aesthetic conventions play in mediating legal knowledge about Asian immigrants. The New York Times, writing about Chae Chan Ping’s deportation in 1889, described him thus: “The name of Chae Chan Ping is now familiar to American ears. He is a Chinese gentleman who has given the United States courts a great deal of trouble in his endeavors to force his unwelcome presence upon the citizens of this fair and free country.”35 Demonstrating the ways in which legal spectacles take on the conventions of fictional narrative forms, his legal battle is framed with the language of literary or theatrical melodrama. He is cast as an aggressive villain struggling to “force his unwelcome presence” on an innocent victim, “the citizens of this fair and free country.”36 The judiciary, in turn, is figured as a heroic patriarch, instructing him to “pack up his traps and be off.”37

In Chae Chan Ping, Justice Stephen Johnson Field issued the first articulation of Congress’s plenary power to, in Pinkerton’s words, “keep out those who are out”: “That the government of the United States, through the action of the legislative department, can exclude aliens from its territory is a proposition which we do not think open to controversy. Jurisdiction over its own territory to that extent is an incident of every independent nation. It is a part of its independence.”38 Thus, Field understood the right of exclusion as a fundamental component of the constitution of sovereignty and the composition of national independence.

Three years later, the Supreme Court reaffirmed this principle in a case that applied the Chae Chan Ping holding to an ethnic Japanese petitioner in Nishimura Ekiu v. United States.39 This 1892 case involved a woman who immigrated to the United States aboard a steamer, pursuing a husband who had previously arrived in the country. Resonating with Cho-Cho-San’s ultimate foreclosure from national belonging and reflecting the particular will to keep Asian women from immigrating to the United States (discussed in greater detail in the next chapter), she was denied entry. Once more, the right of exclusion was defined as a foundational power of the state. But the Nishimura Ekiu court, even more than in Chae Chan Ping, reveals the border as performance by focusing not on territory but instead on the regulation and choreographing of the immigrant’s body as it moves into and across the national space. As Justice Horace Gray wrote, “It is an accepted maxim of international law, that every sovereign nation has the power, as inherent in sovereignty, and essential to self-preservation, to forbid the entrance of foreigners within its dominion, or to admit them only in such cases and upon such conditions as it may see fit to prescribe.”40 In both Chae Chan Ping and Nishimura Ekiu, the act of exclusion produces, defines, and protects the identity of the sovereign nation through the law’s control of the immigrant’s movement across borders. But acts of legal choreography were not enough to manifest and police these borders. Aesthetic practices supported and, in the case of the theater, manifested flesh-and-blood figurations of Asian difference that would confirm and justify these actions in the minds of national audiences.

As we saw in the New York Times reportage on the Chae Chan Ping case, Congress and the courts were described as loving patriarchs, doing away with the villainous threat of Asian invaders with a protective decisiveness. This figuration is not at all dissimilar from the characterization of Pinkerton’s own management of his domestic sphere. Pinkerton’s will to “keep out those who are out” and the “American locks” both reflect the dominant consensus that Asian bodies should be excluded from the nation. At the same time, the United States was grappling with Asian bodies already within national borders. So if Cho-Cho-San’s family can be understood as representative of the “yellow hordes” that had to be excluded, the sanctioned presence of Cho-Cho-San’s “one small maid” (Suzuki) in Pinkerton’s home is significant of this other political dilemma.

Exclusion was often too late because the vacuum of both capitalism and imperialism had already drawn large numbers of Asians into the United States. In a concession to industries and employers who wanted to continue to exploit the labor of Chinese immigrants already within the country, the Chinese Exclusion Act allowed Chinese immigrants who entered before 1882 to leave the country and return, so long as they received a certificate of identification. Shortly before Chae Chan Ping, the Supreme Court issued a ruling in United States v. Jung Ah Lung.41 The case involved a Chinese laborer who left the country with just such a certificate but lost it (reportedly stolen by pirates) before reentry. The justices ruled that this certificate was not the only piece of identification necessary for reentry.42

Not unlike Jung Ah Lung, as a domestic laborer, Suzuki moves in and out of Pinkerton’s house at ease, but this movement should not be confused with absolute inclusion. Her presence is emblematic of a long and ongoing history of the racialization of certain bodies whose status as exploitable labor sources allows them to pass through spaces that are otherwise explicitly closed to them, so long as they carry out the dances of domestic servitude and un(der)compensated labor. But such figures were and often are not to be understood as proper citizens or even subjects of the nation. While the Chinese Exclusion Act allowed Chinese laborers who entered the country prior to 1892 to exit and reenter the country, their presence was juridically figured as illegal. Justice Louis Brandeis observed this fact in Ng Fung Ho v. White, a 1922 case involving Chinese petitioners subject to the mandates of the Chinese Exclusion Act: “One who has entered lawfully may remain unlawfully.”43 In other words, some Chinese laborers were paradoxically tolerated because the state would not always remove them, but their presence was always already illegal in theory of the law. As I discuss in chapter 5, this is a status that continues to attach itself to Asian immigrants in the present. As we shall now see, Cho-Cho-San’s own sanctioned presence in the Pinkerton home explodes into a legal problem of tragic proportions.

Act II. Madame Butterfly and the Problem of Law

Scene 1. Between Interior and Exterior in Long and Belasco’s 1900 Play

If Long’s novella manifests the juridical unconscious of the dominant culture in narrative form, Belasco’s 1900 theatrical adaptation embodied it, giving audiences the rare chance for a flesh-and-blood, theatrical encounter with the exotic and mysterious body of the Asian Other. Turning now to the dramatic adaptation, Long and Belasco’s onstage representation of Cho-Cho-San as a character that blurs clear national and racial distinctions was of particular interest and consternation for audiences and reviewers alike. With white women such as Blanche Bates and later Valerie Bergere and Evelyn Millard playing the role of Cho-Cho-San in yellowface, spectators demonstrated significant angst over whether what they were seeing on the stage was an authentic representation of Japanese femininity.44 The Times complained, for example, “Bates’ portrayal is human and its imitations of Japanese manners and characteristics is facile.”45 Despite the Times’s complaint, it seems the actresses were relatively successful in convincing audiences of their character’s authenticity.

In 1904, Bergere gave an interview in which she described her decision to remain in costume after a performance of the play. A pair of tourists caught view of her and declared, “I tell you it can’t be. She must be a Jap. No white woman could ever play such a role.”46 Bergere kept up the façade, as the tourists followed her through the streets of Times Square, before eventually disclosing her whiteness, to their great disappointment. There is little doubt that Bergere looked completely ludicrous shuffling down Broadway near midnight in what she described as the “short, quick steps of the Japanese,” dressed in a kimono while speaking in “broken English.”47 The spectacle onstage was probably no less stupid. However, the audience’s refusal to acknowledge what was no doubt a clear act of racial mimicry evidences a regulation of the color line so staunch that audiences believed that “no white woman could ever play such a role.”

Belasco’s dramatic adaptation eliminates the debate over the exclusion of Cho-Cho-San’s family. It begins after Pinkerton has already abandoned Cho-Cho-San, as she earnestly awaits his return. Again, the importance of the locks are highlighted as in the opening scene, in which Cho-Cho-San explains to Suzuki why her husband put the locks on the door: “to keep out those which are out, and in, those which are in. Tha’s me.”48 “Tha’s me” identifies Cho-Cho-San’s confused status between interior and exterior, Japan and the United States, linking the regulation of Asian female sexuality to the practice of constituting proper national and racial borders. This form of racial and national confusion between interior and exterior is lifted from Long’s novella and brought to life before the audience’s eyes in the form of the set, described in the script thus: “Everything in the room is Japanese save the American locks and bolts on the doors and windows and an American flag fastened to a tobacco jar. Cherry blossoms are abloom outside, and inside.”49 The symbolic blend between interior and exterior is represented by potent symbols of US and Japanese nationalism (the US flag and the sakura) cohabiting the home. This confusion of cultural and national distinction is embodied in a less harmonious form by the character of Cho-Cho-San. This is specifically realized through her spoken dialogue.

Linguistic utterance becomes a primary method by which Cho-Cho-San’s confused status between the United States and Japan is performed. It is the medium through which the audience can identify her inability to properly perceive her exclusion from both spaces at the very moment she attempts to perform her inclusion in them. The structure of the dialogue signifies the peculiar place of the gendered Asian-immigrant and Asian American subject as always, somehow, located outside the United States. In the opening scene, for example, Cho-Cho-San insists that Suzuki speak English only:

Madame Butterfly: (Reprovingly) Suzuki, how many time I tellin’ you—no one shall speak anythin’ but those Unite’ State’ languages in these Lef-ten-ant Pik-ker-ton’s house? (She pronounces his name with much difficulty.)50

She speaks in a pidgin that draws on and embellishes the dialect spoken by the heroine in Long’s novella. Her insistence on English is at once significant of a desire to enter the United States and indicative of her cultural inability to properly perform ideal US subjectivity. In the novella, she explains that Pinkerton has insisted that she speak “United States’ languages” in his absence.51 If she does this, upon his return, she claims, “he go’n’ take us at those United States America.”52 Cho-Cho-San’s failed attempt to speak in “Unite’ State’ languages” reinforced dominant arguments in support of exclusion: namely, no matter how much Asians in America may attempt to perform ideal US subjectivity through the guiles of cunning and artifice, their innate racial, national, and cultural difference marks them as incapable of fully assimilating into the dominant white culture.

Popular media in the nineteenth century, from news reportage to stage shows such as Madame Butterfly, commonly represented Asian subjects as speaking broken English. The figuration of Asian immigrants burdened with accented English was shorthand for Asian racial difference as that which impedes proper assimilation or the performance of proper national subjectivity. Thus, representations of broken English were inherently tied to the narration of Asian subjects as those that should be excluded from the national body politic. Take, for example, the Times’s description of the final words of Chae Chan Ping, just before his removal from the United States: “He said in pigeon [sic] English: ‘I don’t want to go back to China; I want to stop in California.’”53 Emphasizing his “pigeon” (a spelling error that figures him as both foreign and animalistic, or at least less than human) at the exact moment that he decries his removal from the nation confirms the article’s insistence that the Chinese must be removed and excluded from the United States. Like Cho-Cho-San, his “pigeon” is a means of representing the racialized Asian immigrant’s inability to perform as a proper national subject. It thus justifies his or her exclusion.

The use of dialect to mark the inferiority of racialized bodies was not new. Cho-Cho-San’s dialect, in both Long’s and Belasco’s treatments, is reminiscent of the “darky dialect” central to blackface minstrelsy. This form of dialect was also widely popularized in representations of African Americans in nineteenth-century US American melodrama and literature. As Eric Lott argues, blackface minstrelsy was significant of both a practice of domination and the desire for the dominant white culture to consume black racial difference.54 “Darky dialect” represented African Americans as unintelligible, inferior racialized subjects who were ripe for domination, while staging such subjects as projection screens onto which fantasies about the “liberties of infancy” could be displayed.55 The adoption of similar forms of dialect for the representation of Asian and Asian American subjects achieved similar ends and highlights the ways in which Asian racialization occurred across the differentiated representational landscapes of race in the United States.

That Long’s and Belasco’s adoption of a dialect that was at the very least referential to the dialects of blackface traditions is in keeping with the comparative racialization of Asian and African American subjects in both aesthetic and legal traditions of the era. Krystyn Moon shows how US composers in the nineteenth century, eager to satiate audience desires to consume exotic sounds of the “Orient,” turned to familiar “musical representations of difference” found in blackface minstrelsy: “By combining African American traditions with European Orientalism and transcriptions of Chinese music, they again played to notions of difference and inferiority and expanded on the conflation of the non-Western world.”56 This form of racial triangulation was similarly present in the law, most notably in Harlan’s Plessy dissent, figuring nonwhite racial difference as that which could be simultaneously consumed and excluded in the construction of ideal (white) national subjectivity. Thus, as Julia H. Lee observes, “the figure of the Asian was vital in mediating the relationship between blackness and American national identity, and in turn . . . blackness was key in imagining Asian racial difference in relation to the nation.”57 While the outcomes and effects of such processes were varied for different minoritarian groups, their mutually subordinate construction by the dominant culture bolstered the stability of whiteness as an ideal national subject position.

White audiences reveled in the ability to consume Cho-Cho-San’s dialect as that which signified the fetish of her exotic racial difference, while confirming the subordinate position projected onto racialized bodies by the logic of white supremacy. Her speech patterns thrilled the cosmopolitan New York crowd, as documented by one newspaper reporter who described Bates’s “delivery of Mr. Long’s curious patois as exceedingly interesting.”58 But they also confirmed the fact that she was utterly incompatible within the parameters set by the dominant culture to define ideal national subjectivity. The charming naïveté of Cho-Cho-San’s assumption that the language she is speaking would in any way pass for English is encapsulated by her failure to name it properly. She refers to English erroneously in the plural as “Unite’ State’ languages.” Her radically incommensurate relationship to the United States is thus figured through her speech, which breaks down and becomes incomprehensible as her status between Japan and the United States grows increasingly and tragically confused. Spectacularly exhibiting this contention, her final lines in the play are nearly gibberish: “Well—go way an’ I will res’ now. . . . I wish res’—sleep . . . long sleep . . . an’ when you see me again, I pray you look whether I be not beautiful again . . . as a bride.”59 Belasco and Long make Cho-Cho-San a tragic figure that is confused and confusing, broken, neither here nor there, incomprehensible and thus impossible. It is this incomprehensibility, her incompatibility with US culture and, ultimately, US law which results in Cho-Cho-San’s destruction.

The heroine’s tragic end is prefigured in each version of Madame Butterfly with a legal contract that is beyond her comprehension: the contract establishing Pinkerton’s rental of the home and his marriage to Cho-Cho-San for a period of 999 years. What the audience is told via Pinkerton in all versions and what Cho-Cho-San does not grasp, however, is that Japanese law (according to Long, Belasco, and Puccini) allows Pinkerton to simply walk away from both the house and the marriage without penalty. Looking back to Long’s 1898 novella, for example, we find a detailed discussion of the legal terms that structure the purchase of Pinkerton’s wife and the rental of his home:

With the aid of a marriage-broker, he found both a wife and a house in which to keep her. This he leased for nine hundred and ninety-nine years. Not, he explained to his wife later, that he could hope for the felicity of residing there with her so long, but because, being a mere “barbarian,” he could not make other legal terms. He did not mention that the lease was determinable, nevertheless, at the end of any month, by the mere neglect to pay the rent.60

The metonymic relationship between Cho-Cho-San and the house is established by way of the legal contract. (By the time we get to the opera, this distinction is dissolved, and both the bride and house are rented for 999 years.) Pinkerton, for his part, is protected by his mastery of the law. Understanding the legal limits placed on him by his status as a foreign “barbarian,” Pinkerton manipulates this status to set up a seemingly permanent arrangement that is entirely predicated on his ability to walk away from the house and wife at any point.

The play begins after Pinkerton’s abandonment, and in the first scene, we find Cho-Cho-San pacing the stage and hemorrhaging the limited funds left to her care by her husband on a rent that is beyond her means. She does so believing that (a) she is required to keep up the 999-year lease signed by her husband in his absence because (b) the lease is proof (to her) of his intention to return home. As she declares in the opening scene, while Suzuki counts the dwindling amount of money they are left, “If he’s not come back to his house, why he sign Japanese lease for nine hundred and ninety-nine year for me to live?”61 Belasco inaccurately stages Japan as a state of capricious lawlessness, suggesting that it is the fact that Japanese society exists without the benefit and securities of the US legal contract, and not Pinkerton’s abandonment of Cho-Cho-San, that is the root of the tragedy.62 The burden of blame is further shifted onto the heroine, as she is responsible for ultimately failing to grasp her proper position with regard to national and juridical categories of ideal subjecthood. Put clearly, she fails to comprehend the fact that she is hardly a subject at all but more nearly an object for exchange between nations and men.

All three versions of Madame Butterfly include a crucial scene in which the abandoned Cho-Cho-San is given harsh advice by Sharpless, Pinkerton’s friend who remains concerned with her well-being. In his endeavor, the marriage broker (Gobo) and a Japanese suitor (Yamadori) accompany Sharpless. Each man encourages her to move on and marry again. They assure her that remarriage would be legal given her circumstances. As they attempt to explain to her that her marriage is not binding under Japanese law, Cho-Cho-San rejects their counsel, curiously insisting that she is not subject to Japanese law. She claims, instead, that she is a subject of US legal jurisdiction.

In the dramatic adaptation, the scene unfolds thus:

Yamadori: According to the laws of Japan, when a woman is deserted, she is divorced. (Madame Butterfly stops fanning and listens.) Though I have traveled much abroad, I know the laws of my own country.

Madame Butterfly: An’ I know laws of my husban’s country.

Yamadori: (To Sharpless) She still fancies herself married to the young officer. If your Excellency would explain . . .

Madame Butterfly: (To Sharpless) Sa-ey, when some one gettin’ married in America, don’ he stay marry?

Sharpless: Usually—yes.

Madame Butterfly: Well, tha’s all right. I’m marry to Lef-ten-ant B.F. Pik-ker-ton.

Yamadori: Yes, but a Japanese marriage!

Sharpless: Matrimony is a serious thing in America, not a temporary affair as it often is here.63

This exchange demonstrates the proper orientation of a national subject, which is embodied by the two men. The thoroughly Japanese Yamadori knows “the laws of [his] own country,” and the unflinchingly US American Sharpless knows the laws of his. That proper subjectivity is tied to gender is amplified by the fact that unlike Cho-Cho-San, Yamadori speaks impeccable English. Furthermore, Belasco hierarchically organizes Japanese marital legal conventions as inferior, lacking the “serious” nature of marriage in the United States. We also encounter an implicit critique of US imperialism as Sharpless suggests that marriage is “a serious thing” in the United States (effectively condemning the behaviors of his colleague Pinkerton, who has behaved as if it were not). This is less a critique of US imperialism than of its execution by irresponsible agents like Pinkerton. Sharpless stands in as the ideal model of how US empire should function; he is a stable and responsible moral authority. What is without a doubt, however, is that Cho-Cho-San is confused with regard to both, applying what she understands of US law to herself. Adopting the laws of her “husban’s country,” Cho-Cho-San disavows the laws of Japan, while failing to recognize that she would be completely illegible in the theater of US law.

Scene 2. The Scene of Exception in Puccini’s Opera

The heroine’s crisis is that from a legal and a cultural perspective, she makes no sense. She is neither Japanese nor US American, and within the rigidly segregated logic of the turn of the century, this makes her altogether impossible. This impossibility is temporarily negotiated by the heroine as she shuttles between subjecthood and an objecthood that Long describes as an Oriental curio: “After all, she was quite an impossible little thing, outside of lacquer and paint.”64 Her disavowal of her legal status as a Japanese subject and insistence on her impossible status as a US subject is even more explicit in the same scene in Puccini’s 1907 opera.

In Minghella’s 2006 production of Madama Butterfly, the “serious” nature of US law is counterpoised against the childlike and silly nature of Japanese law. In this scene, the characters inhabit a primarily empty stage, save a wall of white shoji screens behind them. Cio-Cio-San is clad in a preposterous kimono of shocking pink and neon green, and the other Japanese characters wear equally ridiculous colors and towering hats and flap fans as if they were chicken wings. Sharpless grounds the scene with the sobriety of a staid diplomat, wearing a professional, earth-toned suit, sitting patiently on a Western-style chair, as the Japanese characters argue over Cio-Cio-San’s legal status:

Gobo: But the law says.

Butterfly: (interrupting him) I know it not.

Gobo: (continuing) For the wife, desertion

Gives the right of divorce.

Butterfly: (shaking her head) That may be Japanese law,

But not in my country.

Gobo: Which one?

Butterfly: (with emphasis) The United States.

Sharpless: (Poor little creature!)65

The heroine’s confused legal status is emphasized as the “Star Spangled Banner” makes an appearance, flowing under her lilting glissando. Here, the lyric—“La legge giapponese . . . [The Japanese Law . . .]”—and the anthem are placed in counterpoint against each other, suggesting their incompatibility. Then, as she sings, “non gia del mio paese [is not the law of my country],” the anthem meets her melody, and they join together for a brief moment as she sings this lyric in place of the phrase “by the dawn’s early light.”66 The anthem abandons her immediately after Gobo asks, “Which one?” She responds, “The United States,” and the strings cascade into a lower register that broaches an ominous minor-key tonality, setting up Sharpless’s hushed utterance, “Poor little creature!” This statement, rendered as an aside, emphasizes the fact that this is the tragedy of Cio-Cio-San’s situation (from the opera’s point of view): because she is incapable of grasping the concept of territorial jurisdiction, and her exclusion from the United States, she is incapable of properly situating herself as a Japanese legal subject/object.

Cio-Cio-San’s problem is that she has attached herself to an improper and impossible love object (Pinkerton and, by extension, the United States). The Asian-immigrant and Asian American subject’s desire for a place in the United States is thus figured as an inappropriate amorous attachment. This narrative trope was a convenient way of affirming the myth of US exceptionalism (as a place that all people purportedly desire to be a part of), while maintaining firm boundaries regulated by the practice of exclusion. In the New York Times’s coverage of Chae Chan Ping’s deportation, his relationship to the United States is similarly described as an illicit, forbidden, and ultimately one-sided love affair: “Ping’s love of country is confined to this country.”67 Like Cio-Cio-San, his relationship to the state is discursively staged as a failed marriage: “He was . . . wedded to the fascinations of Chinatown, and remained there until the indignant howl of an ever vigilant press awakened the authorities to a realization of the fact that Ping had brought his knitting and intended to stay.”68 Pitiable as Chae Chan Ping or Cio-Cio-San’s romantic national convictions may be, the final solution is unmistakable: negation through exclusion (or death). Locked in a one-way romance, both appealed to the majesty of US justice in the hopes that the state would ultimately recognize their marriage to the United States. Unsurprisingly, both lose their case.

Cio-Cio-San invokes rights that she imagines she has gained through marriage. In all three versions of Madame Butterfly, an exchange occurs in which she paints a detailed portrait of the scene of justice. She describes the ritual of going before a US judge in order to appeal for relief from the injustice of Pinkerton’s abandonment. In each case, she assumes that the judge will perceive her as a subject of US law and protect her accordingly. In the opera, this sequence directly follows the previously discussed scene. After Cio-Cio-San declares herself subject to the laws of the United States, the strings slide into a playful lilt. This is accompanied by tremolos in the wind section that give the scene an air of childlike playfulness. Like the dialect in Long’s and Belasco’s versions of the story, Puccini’s orchestration frames Cio-Cio-San as naïve, foolish, and infantile.69 This is particularly acute when she flutters around the stage with an enthusiastic euphoria as she earnestly lectures Gobo on the nature of US law and her assumed place within it. She complains about the tenuous nature of Japanese marriage, calling on Sharpless to authenticate her critique: “But in America, that cannot be done. (to Sharpless) Say so!”70 Sharpless attempts to interject, “(embarrassed) Yes, yes—but-yet,” and we can assume that he would continue to explain that Cio-Cio-San cannot claim the protections of US law. She will not permit him to continue, however, and sings with august sincerity:

Madame Butterfly: There, a true, honest

And unbiased judge

Says to the husband:

“You wish to free yourself?

“Let us hear why?—

“I am sick and tired

“Of conjugal fetters!”

Then the good judge says:

“Ah, wicked scoundrel,

“Clap him in prison!”71

On the one hand, because Butterfly is clearly wrong, we can interpret the scene as a critique of the bias of the judicial system in the United States. The aria explicitly acknowledges the gendered injustice of a system that would deny the basic claims for justice that a petitioner like Cio-Cio-San might put before a judge. At the same time, Cio-Cio-San’s embodiment reduces her to a stereotype of racialized, gendered subjectivity that is incapable of understanding the complicated vicissitudes and implications of engagement with a justice system that, ultimately, does not recognize her as a proper juridical subject.

As Cio-Cio-San delivers this aria, she bounds around the stage. When she embodies the judge, she stands behind Sharpless’s chair and issues the orders into his ear. As the beseeching husband, she bends on one knee in front of him and begs for release from his “conjugal fetters.” She stands and once again moves behind the chair, delivering the judge’s order with masculine authority, before melting into the opera’s rote physical manifestation of Japanese female sincerity: eyes batting and feet shuffling. (Over a century after the first production of Belasco’s play, it seems directors and performers still turn to Bergere’s “short, quick steps of the Japanese” to signify Japaneseness.) In every way, the scene stages not only the sexist trope of the incapacity of Cio-Cio-San to understand the gravity of her confused legal status but also the ridiculousness of her assumption that she would be perceived by a US judge as a fully recognized subject of US law.

As Cio-Cio-San performs for her imaginary judge, the audience in the theater is given the opportunity to take on another role: that of a jury weighing the merits of her case. In this sense, the scene draws on the classical Athenian roots of Western theater. As J. Peter Euben notes, for the Athenians of antiquity, “drama was as much a political institution as the law courts, assembly, or boule.”72 Indeed, the theater could be a unique place for working through the political debates of the day because it lacked what Carl Schmitt described as the juristic decision that is the determining moment in the law’s realization.73 As Euben observes, “Freed from the urgency of decision which marked other political institutions, drama encouraged inclusive and reflective thinking about contemporary issues.”74 Thus, we locate one of the unique political and legal functions of aesthetic performances in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which carry a trace of their historical ancestors in the Theater of Dionysus.

As reflective of the juridical unconscious of its time, Madame Butterfly encourages the audience-as-jury to weigh the different exigencies behind the case. Unquestionably, the audience is meant to feel sympathy for the heroine. But this sympathy is not necessarily driven by the revelation of an unjust system that excludes her from the sphere of national belonging or the protection of US law. Instead, this sympathy—expressed in Sharpless’s “Poor little creature!”—is colored by condescension. The tragic irony that attaches itself to Cio-Cio-San is born from the fact that Puccini’s Western audience, like Sharpless, knows that she has no place in the United States. It is thus Cio-Cio-San’s infantile inability to grasp this fact (infantile because she is a woman and Japanese) that causes the tragedy. Weighing the evidence, the audience-as-jury is encouraged to reject Cio-Cio-San’s deposition. They are given every reason to rule that the heroine is tragically beyond the jurisdiction of US law. Having been given the opportunity to sympathize with her, however, the liberal sensibilities of the audience can remain intact while the juridical exclusion of Cio-Cio-San proceeds apace.

If we can imagine the evidence leading the audience, however sympathetic, to reject Cio-Cio-San’s plea, we know that the courts of the period most certainly would have. Turning to a set of cases dealing with the question of Asian testimony in US courts shows just how closely the Butterfly narrative functions as a representative of this jurisprudence. It is important to understand how the problem for a subject like Cio-Cio-San was not simply the lack of a “true, honest, and unbiased” judge. Rather, bias was the constitutive element for the exercise of law over the Asian-immigrant and Asian American body. Cio-Cio-San’s fantasy of testifying before a judge against her Caucasian American husband was simply impossible. An evolving jurisprudence in California and the Pacific Northwest was quickly defining Asian bodies as exceptional to the law’s application with regard to questions of due process. This process was helped by the comparative racialization of other racial minorities.

At first, the state tried to manage the threat of Asian racial difference by turning to previous technologies developed to control African American and Native American racial difference, attempting to make the Asian American body “conform to a preformed law.”75 In 1851, for example, the California Congress banned African American and Native American witnesses from testifying against white parties.76 In an 1854 case, People of California v. Hall, the Supreme Court of California considered whether the ban on testimony would extend to Chinese witnesses. Chief Justice Hugh Campbell Murray delivered an astonishing opinion in which he determined that because Christopher Columbus landed in the Americas in an attempt to travel to India, the term Indian as misapplied to Native Americans must also now apply to descendants of Asia: “We have adverted to these speculations for the purpose of showing that the name of Indian, from the time of Columbus to the present day, has been used to designate, not alone the North American Indian, but the whole of the Mongolian race, and that the name, though first applied probably through mistake, was afterwards continued as appropriate on account of the supposed common origin.”77 If Columbus erroneously transformed Native Americans into Asians, the Murray ruling applied a reversal that retroactively transformed Asians into Native Americans. But this alone was not enough, requiring the development of a practice of legal suspension to adequately manage the surprise that Asian racial difference posed to the unity of the ideal body politic.

In two Oregon cases from this period, the Supreme Court of Oregon ruled that Chinese persons could be allowed to stand as witnesses against other Chinese defendants. However, both courts declared that Chinese testimony could only be accepted after suspending the formal requirements of due process. In State of Oregon v. Mah Jim, the court issued a per curium opinion which reasoned that Chinese witnesses against other Chinese parties, though permissible, must be observed with the utmost suspicion: “Experience convinces every one that the testimony of Chinese witnesses is very unreliable, and that they are apt to be actuated by motives that are not honest. The life of a human being should not be forfeited on that character of evidence without a full opportunity to sift it thoroughly.”78 In State of Oregon v. Ching Ling, a murder case two years after Mah Jim, Judge Andrew Jackson Thayer similarly suggested that evidence against a Chinese defendant did not need to live up to the same standards of evidence required for a white defendant. The irreducible racial difference of the Chinese was proffered as the primary reason for this decision: “The testimony was not sufficient to have had any weight whatever as against white persons. . . . As to Chinamen, however, it is different.”79 This difference did not register the Chinese as totally beyond the reach of the law but placed the Chinese body in an exceptional position at the law’s limit: “An attempt to apply strict technical rules in such cases is too apt to result in a sacrifice of substance to form. The law was instituted to secure justice, and its design and purpose should not be suffered to be defeated by a strict adherence to formal rules in its administration. In cases of homicide among these Chinamen, it is almost impossible to ascertain who the guilty parties are.”80 As the court would not apply the “technical rules” of due process to the Chinese, the Agambenian legal ban was realized through law that appears to be in force but suspended.