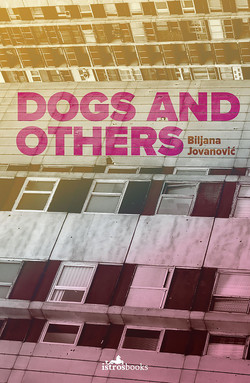

Читать книгу Dogs and Others - Jovanovic Biljana - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTranslator’s Preface

Most names and other proper nouns in this translation have been left in their original Serbo-Croatian (as Jovanović would have said) forms. An exception was made for the most common version of the narrator’s first name, Lidija, which we have rendered as Lidia for the sake of readability.

The text used as the basis for this translation was Biljana Jovanović’s Psi i ostali (Belgrade: Prosveta, 1980).

Understanding This Book

Certain generalizations about plot or style, or specific notes on scenes, hard-won by another reader, can make a complex, or intricate, novel such as this one easier to understand. For instance, without a character list for the whole work, it might be helpful to untangle all the characters whose names begin with the letter ‘M’:

Marina – the mother of Lidia and Danilo, who is mostly absent and often cruel

Marko – Danilo’s dodgy friend

Mihailo – the father of Lidia and Danilo, who hanged himself a decade or so ago

Milena – Lidia’s lover, a friend of Danilo and Čeda Little River

Mira – Danilo’s girlfriend

In terms of style, readers should be aware that Lidia’s narration contains many meta-references (e.g., questions about things she just said) and ‘experienced details’ in the tradition of the French nouveau roman; there are also neologisms (sometimes adjectives, as in ‘crumby’, as opposed to ‘crummy’; but often adverbs, as in ‘postmanly’ and ‘bankerly-cordially’) and, in recorded speech, drawled or drawn-out words spelled with urgently repeated vowels.

Subject matter such as bodily fluids (snot, semen, rheum, secretions connected to sexually-transmitted diseases), raw sexuality, and characters pinioned uncomfortably in the city’s infernal machine might qualify the text as a kind of ‘dirty realism’, but its political content is equally obvious. The settling of accounts of a traditional-minded man (is it a man?) with. second-wave feminism in Chapter 25 is highly unsettling, but instructive.

There are many ways to read, or interpret, this novel. Literary critics have noted that it is here, in her second major work of prose, that Jovanović ‘found her voice’. Indeed, her breakout success from two years earlier (1978), Pada Avala (Eng.: Avala is Falling) became a cult classic; and although it was, in the opinion of this translator, far too transgressive and energetic to deserve the label ‘jeans prose’, that is how it is often designated to this day. But Dogs and Others delivered a wholescale re-imagination of the role of the author and the narrator, and here Jovanović took her art to a different level. (Her third novel, My Soul, My One and Only from 1984, and her unfinished fourth novel from the 1990s, move into different territory yet again.)

Literary scholars, of course, also sort out how this book is put together, how it functions, and why it works. One notices immediately the pell-mell energy of the digressive narration; the intertextuality (various letters, pamphlets, and flashbacks set off from the main text); the mystifying epigraphs; and the free and stubborn images – dreams looking for vocabulary, images looking for form. And yet, the novel holds together. The red threads lead somewhere. The references come home to roost. It’s not a farce, not an ironic romp, not an act of heedless satire or feckless cynicism.

Consideration or analysis of the content of the novel is also both demanding and valuable. Jovanović herself noted that the novel was ‘a debt, a debt to myself, to bring things that seemed important to me at the time out into the open, and to strip them completely naked’. Is this novel the fruit of the evolution of the increasing tide of creditable woman-centred writing in Yugoslavia, distilled into rocket fuel by the addition of feminist sensibilities from the West? How important is the fact that this novel contains what appears to be the first detailed depiction of a sexual relationship between two women in Serbian literature?

Interesting historical explanations, stressing the socio-economic or even political context of the plot and the times in which the manuscript was produced and published, are also possible. Jovanović was too young to be a direct part of the ‘generation of 1968’, but not too young to engage or interact (positively and negatively) with that movement’s causes and ideals. She was definitely too young to be considered one of the ‘children of communism’. Related phenomena such as membership in the ‘red bourgeoisie’ or, as some of her critics might say, her generation’s position as beneficiaries of post-war social mobility who supposedly repaid the system with unruliness or anarchism also miss the mark, but they are in circulation. Also plausible are critiques of work like hers from the Marxist or neo-Marxist; the presence of the Praxis philosophers in Yugoslavia during her lifetime provides a lot of ready material for analysis. One could also take, ideologically or historically, a Titoist perspective, whereby Jovanović’s novels can be seen to deviate from the established canon of ‘socialist aestheticism’ or ‘Partisan realism’. One could also maintain, as does this observer, that Jovanović’s attention to radically new subjects and her transgressive literary innovations amount to social criticism, which in turn represents a kind of urban extension, and logical continuation, of the ‘anti-fascist moment’ of World War II.

John K. Cox, Fargo, USA. 2018

*

This translation is dedicated to William E. ‘Bill’ Schmickle, the most brilliant teacher I ever had. No one ever lit up Founders Hall or Duke Memorial with ideas and lectures and writing the way he did, and no professor ever pushed me as hard or rewarded me as generously.