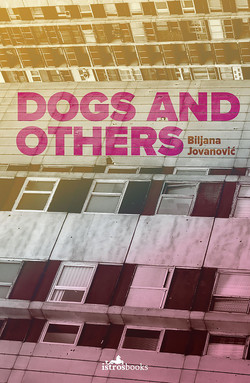

Читать книгу Dogs and Others - Jovanovic Biljana - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIII

‘There will never exist a person who possesses definite knowledge of the gods and of the matters I am talking about. And even if this person were in a position to tell the whole truth, he or she would know that this wasn’t the case. But all people get to have their own imagination.’

– (R.P. Lo4 [X of K.] J.B.)

‘Hey listen, Lidia, last night I had another dream about that riot of colours; first they ran, and then they jostled each other, golden yellow, purplish green and stale wine-red, and dark red, too, and that beige like Mira’s skirt, and a blue, a thin blue colour, you know the one, Lida, it always whizzes by like lightning, my head starts aching from it, it’s like a whistle, Lida, it whizzes and flashes and then goes boom – that’s all she wrote – Lida, are you listening to me?’

I nod my head and think to myself how dead certain I am that Danilo is devouring at least two bars of chocolate at the same time when he chomps and spits so unbearably like this, with saliva running from the corners of his mouth. I go on picking up the newspapers strewn about and say to him: ‘I’m listening to you. Go on!’ And he says: ‘I dreamt that Mira came, with an enormous towel around her head, as if she’d been washing her hair, and all at once everything on her started to drip, like an ice cream cone, just like that, Lidia… Then, behind her, there appeared that guy from a few days ago, the guy with the three sweaters on, d’you hear, Lidia, the guy who slept with that naked fat creature, the one that Grandma said she couldn’t stand to see any more, and she came, too, only I didn’t see her right away; it was only after Mira and the guy got undressed and lay down on that towel from her head; it was like they were cadavers, Lidia, they just lay there and didn’t move any more; and Mira, she was hideously thin… then I saw that fat, naked lady; actually, she came up to me from behind and plugged my ears with some pinkish plugs, terribly hard, and she started rubbing me here, behind my earlobes and then eventually my eyelids, Lida, just imagine that. She was so rude, Lidia! Lidia, is she always so rude? When she started to undress me, it was so unbalanced, by that I mean all from her side, as if she’d gone bonkers, she was shaking all over – she broke the belt loop on my pants and Lidia the moment she touched my zip I went half-crazy and when she unbuttoned me down there I came like a rifle, all over her, Lida, I splattered her everywhere, and she just seemed lost in thought, she pretended that she didn’t see. Afterwards that beige colour spread over us, beige darkness, you understand? Nothing was visible for a while, like looking through watery sand, right up until the pent-up colour came hissing out of Mira’s eyes, with interruptions, like when you pee and have an irregular stream, very similar… Afterwards I saw that you were standing off to one side and you were, like this, look, Lida, on your middle finger like this you were spinning a pair of nail scissors and behind you Jaglika was hopping around, whispering something to you, and then came the worst part with the colours, Lida, are you listening to me… and Lida, stop that now, stop it, Lida, sit down…’

Danilo wasn’t actually munching on any chocolate, but he did, however, have something in his mouth, and that’s why he was talking so slowly; and an enormous lie was rolling around on his palate, between his teeth, and burst forth from under his tongue, Danilo’s speech was unintelligible, Danilo was lying, sizzlingly, spraying on all sides like Jaglika – who ever since that day was no longer able to walk, as if her legs had been hit by a thunderbolt (Jaglika, sweet Jaglika, she knows that the devil himself had sent some invisible boulders rolling down, and that’s why she couldn’t move), or perhaps that blue colour that Danilo never ceases dreaming about, the blue thin one, flashes, goes bang and that’s all she wrote… But all of it together, a phantasmagoria in Svetosavska Street. Danilo and Jaglika, the heroes of a cartoon in fiery blue, with a devil who bombards people with stones, and with Mira’s ice-cream tan skirt.

‘Danilo, it looks like you’ve become unhinged.’ He was looking at me with a crooked smile, like a crook (am I imagining this?), but the very next moment, with his eyes half-closed from fear (I could see quite well the tiny white particles of rheum in between his eyelashes) and with his head turned aside just a touch – out of fright – it was as if I was holding a whip in my hands, and not his moist smelly shirt. I yelled: ‘You told my dream… my dream – and you distorted it completely, you idiot. Idiiiot… You made up half of it… My dream, you animaaal!’ But Danilo wasn’t scared any more (that was also my imagination) but rather dejected and embarrassed, Danilo the five-year-old boy, Jaglika’s most beloved little grandson, using this for a moment to garner all the security he could – from the very fact that everybody else loved him more than me, and that all of them (all of whom?) at that moment were standing at his back and with composure, and a taunt of sorts, he says, ‘But Lida, calm down! Everybody all around can hear. I had that dream, I dreamt it last night, Lida, calm down, I beg you… Just drop it… Lida, really, I…’

I’d had enough: I ripped his shirt; once more he gave me such a weird look that I didn’t know what was going on… that thing with his eyes (he’s cross-eyed) or something else connected with the ripped shirt, or with my wrath, or because he knew… he was looking at me like that because he knew that I had related that dream recently, but of course Danilo also knew that I’d told that dream only to him.

After the torn shirt, it was his leg’s turn, and his head’s and shoulder’s, anything, I wanted to hit him… But all I did was kick him, not all that hard, no, definitely not hard enough to make him scream and call out for Jaglika; then I pulled him by his hair and when I truly was about to hit him (no, I did want to kill him: in my hand was a heavy, sharp object, one without a blade), he turned around so contorted, and twisted (scoliosis?), pulled away, and ran off to Jaglika – in the direction of her omnipotent lap – as if she could help him!

Anyway, Jaglika couldn’t see how the dreams meant anything to her, dreams were just omens, indicators of the events of future days; at night she dreamt and in the daytime it came true, at least a little bit, at least in part – and that was sufficient – that was enough for her; all the rest was frightful stupidity that only silly people messed with: Danilo and I. Poor Jaglika wasn’t going to get it even after she was dead; she was never going to get this dream thing. Even if a hundred of her Hymenopterae started work on convincing her, whispering into her bulbous ears – covered in little curly grey locks of her already faded hair, even if I do say so, one hundred souls of her ancestors would gather and like one terribly complicated tribe – forgetting the quarrels and discord that belong to time – for they are hymenopterous timeless beings (Jaglika did not allow an insect of any kind to be killed in her room, in fact, not even a flying one) and started enthusiastically to persuade her to put dreams aside – someplace where there’s room for them so that she does not touch them, or interpret them, so that she doesn’t conceive of them by any means (not for anything in the world) as theirs or anyone else’s and especially not divine messages; Jaglika would make fun of them, dismiss us with a wave of her hand, laugh at them again, rub her right eye and her left eye (the lid) and again, my God, again she’d laugh at them … and then it could happen that she would say: ‘I know more about dreams than all of you over there from that gang that gets together and dreams about everything and does nothing else, and afterwards you hold court and talk and then go and dream some more and on and on, again and again… I know more, more about dreams.’

‘Jaglika, when you’re dreaming, do you know it’s a dream; do you know while you’re asleep that you are dreaming?’ – I asked her, very much anticipating that she would betray some secret to me, or something very much like a secret. But Jaglika gave me a look like the Devil himself (her power over me was the certainty of an animal, the neighbour’s dog, let’s say, when it is squatting to piss – the way Jaglika does, by the way – the dog is a female, and for me, as for all wretches, there’s nothing left to do but amass and harbour hatred towards dogs and Jaglika) and she said, ‘Oh, you miserable girl, and I thought you were smarter than that.’

If I didn’t know that I was dreaming when I’m dreaming, I could with total presence of mind state that dreams were definite, in the way that reality is; that they are a parallel world and how it’s in point of fact my personal dichotomy (in the back, by the occipital bone); I could even rejoice at the lack of necessity of subsequent connection, of the subordination of dreams to reality or of reality to dreams, which is actually what Jaglika and the whole world do, or the whole world and Jaglika: what harmony! The whole difficulty, however, lies in the fact that, when I dream, that’s when I have some half-retarded control that constantly warns me that I’m dreaming, I’m only dreaming, and then, thank God, all the knives, the awls, the daggers with their sundry grips and all their various blades sticking in my neck and my fingers and face, and more often in strangers’ faces and in everybody’s backs and everyone’s eyes – they look like plastic children’s toys, bendable and soft and harmless; but they aren’t, they are not that at all; and at any rate I have no control like that (no distance from my own self) when I’m not dreaming; and so, thanks to the terrible disproportionality between sleep and so-called wakefulness (or whatever other names that marvel goes by) and a little indirect mediation here and a little direct intervention there, I am in a double trap, and that worries Jaglika, my mother Madame Marina, and Marina’s husband: they would all say, flat out and one after the other, and rightly so, with complete rectitude and perfect indifference: ‘It’s all your own fault,’ like that time twenty-five years ago or more when for the first time I ruined a pair of newly purchased shoes (Marina maintained that I’d deliberately spent the entire morning standing in a puddle: ‘This is all your fault. You’re not getting any new ones.’ I wore wet shoes that whole semester – I absolutely could not get them to dry out. But no – I wore an old pair, all ripped up.

And Danilo? Danilo takes my dreams, he lies and he steals, and he stays silent about his own dreams, not a word, not a syllable, but nothing and utterly nothing; only occasionally, when he is with Jaglika, does he whisper something. Danilo is my informer; he rats my dreams out to me, and rats me out to Jaglika. Could it be that Danilo simply has no dreams? He does not even sleepwalk, although that’s a most ordinary, trivial thing; but consequently he peers through the lock into my room while I’m sleeping (he’s been awake for several years running) and he steals what I’m dreaming about, and later he tells it to Jaglika, but only to her, fortunately.

A Picture from Childhood

Marina took Danilo and me to Tivoli one time! She arranged my left hand across Danilo’s right, squeezed our fingers (safety snaps), and then she checked the buttons on our identical coats, turned up our collars – she thought (at the time) that the wind was blowing but in fact it wasn’t (I know it wasn’t); she ran her hand quickly, impatiently, across our heads (the backs of two identical heads) and, as always, both Danilo and I felt the electricity popping from her palm. I thought (at the time) that faces were distorted and became half-shy or half-perverted grins – creditable grins, like masks at New Year’s – all because of this little current from Marina’s palm; but it wasn’t like that, it wasn’t that; Marina knows that it wasn’t because of that. Then she told us: ‘Go walk around a bit!’ For the first few moments, while she was still right behind our backs (like a policeman on the beat – the parent’s burden) and our identical itsy-bitsy smoothed-down heads, we walked along (three or four or five steps) like we were glued together – so we’d make the right impression on Marina, and then we both set off running without letting go of each other’s hands and we soon fell down. Danilo hurt his chin and scraped both of his arms (his coat tore), and it was probably the exact same for me. Okay, maybe it wasn’t his arms or shoulders, but his knees, it’s quite likely that it was his knees, but I can’t rule out that the scrapes and scratches were everywhere – on all the hard parts of his body. From that point on, the weird things started happening: whenever Marina would take us to the park, the woods, or for a ride on the merry-

go-round, Danilo and I, although our hands were not hooked together, walked pressed up against one another and when we’d start to run, always, the same thing always happened, the same strange thing: it was as if we tripped each other up but no one else saw it, no one else could see it, and we would crash into each other. Then Marina, practical and wise (indifferent), when we had in the course of just one spring ruined all our trousers and jumpers, decided to keep us far apart from each other; at first, when she took us to the park or the woods or anywhere like that, she put herself in the middle, in between us (my God, it was meters of distance… let’s say, without exaggerating, it was two full meters), with me on the left side and Danilo on her right. When we came back it was vice-versa, Danilo on her left side and me on the right. In the lift it was one of us in front (underneath, with your head below her large maternal bosom) and the other in back, with your head at the level of her waist. Indeed, in the lift there was truly no chance (or only a negligible one) for activity that would result in torn clothing, but Marina, being practical and enterprising (those two things go together) and, a third thing, too – efficient, careful (those are one and the same) – considered precautionary measures everywhere at any time and in any place (great or small) to be indispensable, even though it might strike a person (a figure) on the outside as silly and superfluous.