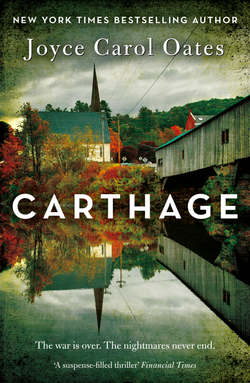

Читать книгу Carthage - Joyce Carol Oates - Страница 12

ОглавлениеTHREE

The Father

OH DADDY WHY’D YOU call me such a name—Cressida.

Because it’s an unusual name, honey. And it’s a beautiful name.

FIRE SHONE INTO the father’s face. His eyes were sockets of fire.

He hadn’t the strength to open his eyes. Or the courage.

The doe’s torso had been torn open, its bloody interior crawling with flies, maggots. Yet the eyes were still beautiful—“doe’s eyes.”

He’d seen his daughter there, on the ground. He was certain.

The sick-sliding sensation in his gut wasn’t unfamiliar. In that place, again. The place of dread, horror. Guilt. His fault.

And how: how was it his fault?

Lying on his back and his arms flung wide across the bed—(he remembered now: they’d brought him home, to his deep mortification and shame)—that sagged beneath his weight. (Last time he’d weighed himself he’d been, dear Christ, 212 pounds. Heavy and graceless as wet cement.)

A memory came to him of a long-ago trampoline in a neighbor’s backyard when he’d been a child. Throwing himself down onto the coarse taut canvas that he might be sprung into the air—clumsily, thrillingly—flying up, losing his balance and falling back, flat on his back and arms sprung, the breath knocked out of him.

On the trampoline, Zeno had been the most reckless of kids. Other boys had to marvel at him.

Years later when his own kids were young it had become common knowledge that trampolines are dangerous for children. You can break your neck, or your back—you can fall into the springs and slice yourself. But if he’d known, as a kid, Zeno wouldn’t have cared—it was a risk worth taking.

Nothing in his childhood had been so magical as springing up from the trampoline—up, up—arms outflung like the wings of a bird.

Now, he’d come to earth. Hard.

HE’D TOLD THEM like hell he was going to any hospital.

Fucking hell he was not going to any ER.

Not while his daughter was missing. Not until he’d brought her back safely home.

He’d allowed them to help him. Weak-kneed and dazed by exhaustion he hadn’t any choice. Falling on his knees on sharp rocks—a God-damned stupid thing to have done. He’d been pushing himself in the search, as his wife had begged him not to do, as others, seeing his flushed face and hearing his labored breath, had urged him not to do; for by Sunday afternoon there must have been at least fifty rescue workers and volunteers spread out in the Preserve, fanning in concentric circles from the Nautauga River at Sandhill Point where it was believed the missing girl had been last seen.

It was the father’s pride, he couldn’t bear to think that his daughter might be found by someone else. Cressida’s first glimpse of a rescuer’s face should be his face.

Her first words—Daddy! Thank God.

HE’D HAD SOME “heart pains”—(guessed that was what they were: quick darting pains like electric shocks in his chest and a clammy sensation on his skin)—a few times, nothing serious, he was sure. He hadn’t wanted to worry his wife.

A woman’s love can be a burden. She is desperate to keep you alive, she values your life more than you can possibly.

What he most dreaded: not being able to protect them.

His wife, his daughters.

Strange how when he’d been younger, he hadn’t worried much. He’d taken it for granted that he would live—well, forever! A long time, anyway.

Even when he’d received death threats over the issue of Roger Cassidy—defending the “atheist” high school biology teacher when the school board had fired him.

He’d laughed at the threats. He’d told Arlette it was just to scare him and he certainly wasn’t going to be scared.

Just last month his doctor Rick Llewellyn had examined him pretty thoroughly in his office. And an EKG. No “imminent” problem with his heart but Zeno’s blood pressure was still high even with medication: 150 over 90.

Blood pressure, cholesterol. Fact is, Zeno should lose twenty pounds at least.

On the bed he’d tried to untie and kick off the heavy hiking boots but there came Arlette to pull them off for him.

“Lie still. Try to rest. If you can’t sleep for Christ’s sake, Zeno—shut your eyes at least.”

She was terrified of course. Fussing and fuming over him to deflect her thoughts from the other.

That morning at about 4 A.M. she’d wakened him. When she’d discovered that Cressida hadn’t come home. Since that minute he’d been awake in a way he was rarely awake—all of his senses alert, to the point of pain. Stark-staring awake, as if his eyelids had been removed.

A search. A search for his daughter. A search that was for a missing girl.

These searches of which you hear, occasionally. Often for a lost child.

A kidnapped child. Abducted.

You hear, and you feel a tug of sympathy—but not much more. For your life doesn’t overlap with the lives of strangers and their terror can’t be shared with you.

Was he awake? Or asleep? He saw the steeply hilly forest strewn with enormous boulders as in an ancient cataclysm and from behind one of these a girl’s uplifted hand, arm—a glimpse of a naked shoulder which he knew to be badly bruised . . . Oh Daddy where are you. Dad-dy.

“Lie still. Please. If something happens to you at such a time . . . ”

The voice wasn’t Cressida’s voice. Somehow, Arlette had intervened.

He knew, his wife didn’t trust him. Married for more than a quarter of a century—Arlette trusted Zeno less readily than she’d done at the start.

For now she knew him, to a degree. To know some men is certainly not to trust them.

She was breathless, irritated. Not terrified—not so you’d see—but irritated. The house was crowded with well-intentioned relatives. There were police officers coming and going—their ugly police-radios crackling and squawking like demented geese. There were reporters for local media eager for interviews—they were not to be turned away, for they would be useful. And photos of Cressida had to be supplied, of course.

Coffee? Iced tea? Grapefruit juice, pomegranate juice? With a grim sort of hostess-gaiety Arlette offered her visitors refreshments, for she knew no other way to deal with people in her house.

Somehow, before she’d had a chance to call her sister Katie Hewett, Katie had come to the house. This was by 10 A.M. Katie had taken over the hostess-role and was helping Arlette answer phones—family phone, cell phones—which rang frequently and with each call, despite the evidence of the caller ID, there was the hope that the next voice they heard would be Cressida’s.

Hi there! Gosh! I just saw on TV that I’m “missing”. . .

Wow. Sorry. Oh God you won’t believe what happened but I’m OK now . . .

Except the voice was never Cressida’s. Remarkable, how it was never Cressida’s.

Years ago Arlette would have crawled beside her husband in their bed, in a crisis like this; she would not have minded that her husband had sweated through his clothes, T-shirt and khaki shorts that were now clammy-cool, and smelled of his body; she would have held the anguished man in her arms, to shield him. And Zeno would have gathered his wife in his arms, to shield her. Shivering and shuddering and dazed with exhaustion but together in this terrible time.

Now, Arlette tugged at his hiking boots—so heavy! And the laces needing to be untied. Pulled the boots off his enormous feet seeing that, even in the rush of preparing to leave for the Nautauga Preserve, he’d remembered to put on a double pair of socks—white liner socks, light-woolen socks.

For all his careless-seeming ways, Zeno was a meticulous man. A conscientious man. The only mayor of Carthage in recent decades who’d left office—after eight years, in the 1990s—with a considerable surplus in the city treasury, and not a gaping deficit. (Of course, it was a quasi-secret that Mayor Mayfield had written personal checks for a number of endangered projects—parks and recreation maintenance, Little League softball, the Black River Community Walk-In Clinic.) One of the few mayors in all of upstate New York who, as he’d liked to joke, hadn’t even been investigated, let alone indicted, tried and convicted, for malfeasance in office.

Arlette had asked the young man who’d driven Zeno home in Zeno’s Land Rover what had happened to him in the Preserve, for she knew that Zeno would never tell her the truth.

He’d said, Zeno had gotten overheated. Over-tired. Dehydrated.

He’d said this was why it isn’t a good idea, a family member to be searching for someone in his family who’s been reported lost.

Zeno smiled a ghastly smile. Zeno managed to speak, for Zeno must always have the last word.

OK, he’d try to sleep. A nap for an hour maybe.

Then, he intended to return to the Preserve.

“She can’t be there a second night. We can’t—that can’t—happen.”

He stumbled on the stairs. Didn’t hear Katie speak to him, and didn’t seem to register that WCTG-TV was coming to the house to do an interview with the parents of the missing girl for the Sunday 6 P.M. news, later that afternoon.

Arlette had accompanied Zeno upstairs trying unobtrusively to slip her arm around his waist, but he’d pushed from her with a little snort of indignation.

He’d needed to use the bathroom, he said. Needed some privacy.

“I’m not going to croak in here, hon—I promise.”

This was meant to be humor. Just the word croak.

She’d made a sound like laughter, or the hissing rejoinder to laughter, and turned away, and left the man to his privacy.

Almost, they were adversaries now. Grappling together each knowing what must be done, what should be done, annoyed with the other for being blind, stubborn.

Arlette had known he’d become overheated in the Preserve, he’d had no right to rush off like that tramping through underbrush while she was alone at the house. Waiting for a call—calls. Waiting for something to happen.

After a distracted hour she returned to check on Zeno: he was sprawled on the bed only partly undressed. As if he’d been too exhausted to do more than pull off his khaki shorts and let them fall to the floor.

Sprawled, breathing hoarsely and wetly, through his mouth, like a beached whale might breathe. And his face slack putty-colored, you’d never have guessed had been a handsome face not so long ago.

Unshaven. Wiry whiskers sprouting on his jaws.

Zeno Mayfield was a man who had to be prevented from pushing himself too hard. As if he had no natural sense of restraint, of normal limits.

As, when he’d been a young attorney taking on difficult cases—hopeless cases—unpopular cases; once, unforgivably, taking on a case so controversial, anonymous callers had threatened him and his family and Arlette had worried that some madman might mail a bomb, or affix a bomb to one of their cars. In the name of God think what you are doing, man—one of the anonymous notes had warned.

All Zeno had done, he’d protested, was defend a high school biology teacher who’d been suspended from his job for having taught Darwinian evolutionary theory to the exclusion of “creationism.”

And when he’d been mayor of Carthage, an exhausting and quixotic venture into “public service” that had paid a token salary—(fifteen hundred annually!)—he’d pushed himself beyond what even his avid supporters might have expected of him and saw his popularity plummet nonetheless. The most controversial issue of Zeno’s mayoralty had been a campaign to install recycling in Carthage—yellow barrels for bottles and cans, green barrels for paper and cardboard. You’d have thought that Zeno Mayfield was a descendant of Trotsky! His daughters had asked plaintively Why do people hate Daddy? Don’t they know how funny and nice Daddy is?

Arlette hadn’t lain down beside him. She hadn’t held him tight in her arms. But she’d laid a cloth over his face, dampened with cold water, and he’d pushed it off and clutched anxiously at her hand.

“Lettie—d’you think—he did something to her? And now he’s ashamed, and can’t tell us? Lettie—d’you think—oh God, Lettie . . . ”

YOUR MOTHER AND I chose our daughters’ names with particular care. Because we don’t think that either of you is ordinary. So an ordinary name isn’t appropriate.

He was solemn and dogged trying to explain. She was younger than the age she was now and rudely she laughed.

Bullshit, Daddy. That is such bullshit.

It was like Cressida to laugh in your face. Squinch up her face like a wicked little monkey. Her laughter was high-pitched like a monkey’s chittering and her small shiny-black eyes were merry with derision.

They were in someplace Zeno didn’t recognize. Not in the forest now but in a place meant to be this place—the Mayfield home.

Why is it, when you dream about a place meant to be “home”—or any “familiar” place—it never looks like anything you’d ever seen before?

He was trying to explain to her. She was making her silly-little-girl face rolling her eyes and batting away his words as she’d have batted away badminton birdies with both her balled-up fists.

Saying Bullshit Daddy, except for her face Juliet is O-R-D-I-N-A-R-Y.

Zeno took exception to this. Zeno was angered when his bright unruly younger daughter mocked his sweetly-serene and beautiful elder daughter.

And anyway it wasn’t true. Or it was a partial truth. For Juliet’s beauty wasn’t exclusively her face.

The exchange between the father and Cressida was a dream. Yet, the exchange had taken place more or less in this way, years before.

The Mayfield girls were like the daughters of a fairy-tale king.

Bitterly the younger daughter resented the fact—(if it was a fact, it was unprovable)—that the father loved the elder, more beautiful daughter more than he loved her, whose twisty little heart he couldn’t master.

I love both our girls. I love them for different reasons. But equally.

And Arlette said I hope you do. And if you don’t, or can’t—I hope you can disguise it.

All parents know: there are children who are easy to love, and children who are a challenge to love.

There are radiant children like Juliet Mayfield. Guileless, shadowless, happy.

There are difficult children like Cressida. Steeped in the ink of irony as if in the womb.

The bright happy children are grateful for your love. The dark twisty children must test your love.

Maybe Cressida was “autistic”—in grade school, the possibility had been raised.

Later, in high school the fancier epithet “Asperger’s” was suggested—with no more validation.

If Cressida had known she’d have said, airily—Who cares? People are such idiots.

Zeno supposed that in secret, Cressida cared very much.

It was clear that Cressida resented how in Carthage, among people who knew the Mayfields, she was likely to be described as the smart one while her sister Juliet was the pretty one.

How much would an adolescent girl rather be pretty, than smart!

For of course, Cressida was invariably judged too smart.

As in too smart for her own good.

As in too smart for a girl her age.

When she’d first started school, she’d complained: “Nobody else is named ‘Cressida.’ ”

It was a difficult name to pronounce. It was a name that fitted awkwardly in the mouth.

Her parents had said of course no one else was named “Cressida” because “Cressida” was her own special name.

Cressida had considered this. She did think of herself as different from other children—more restless, more impatient, more easily vexed, smarter—(at least usually)—quicker to laugh and quicker to tears. But she wasn’t sure if having a special name was a good idea, for it allowed others to know what might be better kept secret.

“I hate it when people laugh at me. I hate it if they call me ‘Cress’—‘Cressie.’ ”

She was one of those individuals, less frequently female than male, whose names couldn’t be appropriated—like a Richard who refuses to be diminished to “Dick,” or a Robert who will not be “Bob.”

When she was older and may have felt a little (secret) pride in her unusual name, still she sometimes complained that other people asked her about it; for other people, including teachers, were likely to be over-curious, or just rude: “ ‘Cressida’ makes me feel self-conscious, sometimes.”

Or, with a downward tug of her mouth, as if an invisible hook had snagged her there, “ ‘Cressida’ makes me feel accursed.”

Accursed! This was not so remarkable a word for Cressida, as a girl of twelve who loved to read in the adult section of the Carthage Public Library, particularly novels designated as dark fantasy, romance.

Of course, Cressida had looked up her name online.

Reporting to her parents, incensed: “ ‘Cressida’—or ‘Criseyde’—isn’t nice at all. She’s ‘faithless’—that’s how people thought of her in the Middle Ages. Chaucer wrote about her, and then Shakespeare. First she was in love with a soldier named Troilus—then she was in love with another man—and when that ended, she had no one. And no one loved her, or cared about her—that was Cressida’s fate.”

“Oh, honey, come on. We don’t believe in ‘fate’ in the U.S. of A. in 1996—this ain’t the Middle Ages.”

It was the father’s prerogative to make jokes. The daughter twisted her mouth in a wounded little smile.

The previous fall when Cressida was a freshman at St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, she reported back that one of her professors had remarked upon her name, saying she was the “first Cressida” he’d ever encountered. He’d seemed impressed, she said. He’d asked if she’d been named for the medieval Cressida and she’d said, “Oh you’ll have to ask my father, he’s the one in our family with delusions of grandeur.”

Delusions of grandeur! Zeno had laughed but the remark carelessly flung out by his young daughter had stung.

AND ALL THIS while his daughter is awaiting him.

His daughter with black-shining eyes. His daughter who (he believes) adores him and would never deceive him.

“Maybe she’s returned to Canton. Without telling us.”

“Maybe she’s hiding in the Preserve. In one of her ‘moods’ . . .”

“Maybe someone got her to drink—got her drunk. Maybe she’s ashamed . . .”

“Maybe it’s a game they’re playing. Cressida and Brett.”

“A game?”

“ . . . to make Juliet jealous. To make Juliet regret she broke the engagement.”

“Canton. What on earth are you saying?”

They looked at each other in dismay. Madness swirled in the air between them palpable as the electricity before a storm.

“Jesus. No. Of course she hasn’t ‘returned’ to Canton—she was deeply unhappy in Canton. She doesn’t have a residence in Canton. That’s insane.” Zeno wiped his face with the damp cloth Arlette had brought him earlier, that he’d flung aside onto the bed.

Arlette said: “And she and Brett wouldn’t be ‘playing a game’ together—that’s ridiculous. They scarcely know each other. And I don’t think that Juliet was the one to break the engagement.”

Zeno stared at his wife. “You think it was Brett? He broke the engagement?”

“If Juliet broke it, it wasn’t her choice. Not Juliet.”

“Lettie, did she tell you this?”

“She hasn’t told me anything.”

“That son of a bitch! He broke the engagement—you think?”

“He may have felt that Juliet wanted to end it. He may have felt—it was the right thing to do.”

Arlette meant: the right thing to do considering that Kincaid was now a disabled person at twenty-six.

Not so visibly disabled as some Iraq/Afghanistan war veterans in Carthage, except for the skin-grafts on his head and face. His brain had not been seriously injured—so it was believed. And Juliet had reported eagerly that doctors at the VA hospital in Watertown were saying that Brett’s prognosis, with rehab, was “good”—“very good.”

Before dropping out impulsively, after 9/11, to enlist in the U.S. Army with several friends from high school, Brett had taken courses in finance, marketing, and business administration at the State University at Plattsburgh. Zeno had the idea that the kid hadn’t been highly motivated—as Kincaid’s prospective father-in-law, he had some interest in the practical side of his daughter’s romance, though he didn’t think he was a cynic: just a responsible dad.

(Juliet would never forgive him if she’d known that Zeno had managed to see Brett Kincaid’s transcript for the single semester he’d completed at SUNY Plattsburgh: B’s, B+. Maybe it was unfair but Christ, Zeno Mayfield wanted for his beautiful daughter a man just slightly better than a B+ at Plattsburgh State.)

He’d tried—hard!—not to think of Brett Kincaid making love to his daughter. His daughter.

Arlette had chided him not to be ridiculous. Not to be proprietary.

“Juliet isn’t ‘yours’ any more than she’s mine. Try to be grateful that she’s so happy—she’s in love.”

But that was what disturbed the father—his firstborn daughter, his sweet honeybunch Juliet, was clearly in love.

Not with Daddy but with a young rival. Good-looking and with the unconscious swagger of a high school athlete accustomed to success, applause. Accustomed to the adoration of his peers and to the admiration of adults.

Accustomed to girls: sex. Zeno felt a wave of purely sexual jealousy. Nothing so upset him as glimpsing, by chance, his daughter and her tall handsome fiancé kissing, slipping their arms around each other’s waist, whispering, laughing together—so clearly intimate, and comfortable in their intimacy.

That is, before Brett Kincaid had been shipped to Iraq.

Initially Zeno had wanted to think that the kid had had too easy a time, cutting a swath through the Carthage high school world with an ease that couldn’t prepare him for the starker adult world to come. But that was unfair, maybe: Brett had worked at part-time jobs through high school—his mother was a divorcée, with a low-paying job in County Services at the Beechum County Courthouse—and he was, as Juliet claimed, a “serious, committed Christian.”

It was hard to believe that any teenaged boys in Carthage were “Christians”—yet, this seemed to be the case. When Zeno had been active in the Carthage Chamber of Commerce he’d encountered kids like these, frequently. Girls like Juliet hadn’t surprised him—you expected girls to be religious. In a girl, religious can be sexy.

In a boy like Brett Kincaid it seemed like something else. Zeno wasn’t sure what.

Recalling how Brett had said, at the going-away party for him and his high school friends, each enlisted in the U.S. Army and each scheduled for basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, that he wanted to be the “best soldier” he knew how to be. (His own father had “served” in the first Gulf War.) Winter/spring 2002 had been an era of patriotic fervor, following the terrorist attack at the World Trade Center the previous September; it had not been an era in which individuals were thinking clearly, still less young men like Brett Kincaid who seemed truly to want to defend their country against its enemies. How earnestly Brett had spoken, and how handsome he’d been in his U.S. Army dress uniform! Zeno had stared at the boy, and at his dear daughter Juliet in the crook of the boy’s arm. His heart had clenched in disdain and dread as he’d thought Oh Jesus. Watch out for this poor sweet dumb kid.

And now recalling that poignant moment, when everyone in the room had burst into applause, and Juliet’s face had shone with tears, Zeno thought Poor bastard. It’s a cruel price you pay for being stupid.

Difficult for Zeno Mayfield who’d come of age in the late, cynical years of the Vietnam War to comprehend why any intelligent young person like Brett Kincaid would willingly enlist in the military. Why, when there was no draft! It was madness.

Wanting to “serve” the country—whose country? Virtually no political leaders’ sons and daughters enlisted in the armed services. No college-educated young people. Already in 2002 you could figure that the war would be fought by an American underclass, overseen by the Defense Department.

Yet Zeno hadn’t spoken with Brett on this subject. He knew that Juliet didn’t want him to “intrude”—Zeno had such ideas, such plans, for everyone in his orbit, he had to make it a principle to keep clear. And he hadn’t felt close enough to the boy—there was an awkwardness between them, a shyness in Brett Kincaid as he shook hands with Zeno Mayfield, his prospective father-in-law, he’d never quite overcome.

Often, Brett had called him “Mr. Mayfield”—“sir.”

And Zeno had said to call him “Zeno” please—“We’re not on the army base.”

Zeno had laughed, made a joke of it. But it disturbed him, essentially. His prospective son-in-law was uneasy in his presence which meant he didn’t like Zeno.

Or maybe, didn’t trust Zeno.

In the matter of the military, for instance. Though Zeno hadn’t tried to talk him out of enlisting, Zeno hadn’t made a point of congratulating him, either, as everyone else was doing.

Serve my country. Best soldier I can be.

Like my dad . . .

There was a father, evidently. An absent father. A soldier-father who’d disappeared from Carthage twenty years before.

Brett had been brought up some kind of Protestant Christian—Methodist, maybe. He wasn’t critical, questioning. He wasn’t skeptical. He wanted to believe, and so he wanted to serve.

Chain of command: you obeyed your superior officer’s orders as he obeyed his superior officer’s orders as he obeyed his superior officer’s orders and so to the very top: the Administration that had declared war on terror and beyond that Administration, the militant Christian God.

None of this was questioned. Zeno wouldn’t have wished to stir doubt. He’d defended the high school biology teacher Cassidy who’d taught Darwinian evolutionary theory to the exclusion of “creationism”—more specifically, Cassidy had ridiculed “creationism” in the classroom and deeply offended some students—and their parents—who were evangelical Christians; Zeno had defended Cassidy against the Carthage school board, and had won his case, but it had been a Pyrrhic victory, for Cassidy had no professional future in Carthage and had been soundly disliked for his “arrogant, atheistic” stance. And Zeno Mayfield had suffered a good deal of abuse, too.

Except that Brett Kincaid had become engaged to his daughter Juliet, Zeno had no wish to enlighten the boy. You had to learn to live with religion, if you had a public career. You had to know when to be quiet about your own skepticism.

Juliet belonged to the Carthage Congregationalist Church: she’d made a decision to join when she was in high school, drawn to the church by a close friend; after she and Brett began seeing each other, Brett accompanied her to Sunday services. No one else in the Mayfield family attended church. Arlette described herself as “a mild kind of Protestant-Christian-Democrat” and Zeno had learned to parlay questions about faith by saying he was a “Deist”—“In the hallowed tradition of our American Founding Fathers.” Zeno found serious talk of religion embarrassing: revealing what you “believed” was a kind of self-exposure not unlike stripping in public; you were likely to reveal far more than you wished. Cressida bluntly dismissed religion as a pastime for “weak-minded” people—she’d gone to church with her older sister for a few months when she’d been in middle school, and been bored silly.

Strange how Cressida could be right about so much, and yet—(this was not a thought Zeno allowed himself to express aloud)—you resented her remarks, and were inclined to dislike her for making them.

Juliet’s Christian faith had certainly been a great solace to her, since news had come of her fiancé’s injuries—a hurried and incoherent phone message from Brett’s mother had been the first they’d heard; she’d been grateful, and never ceased proclaiming her gratitude, that Brett hadn’t been killed; that God had “spared him.”

The shock to Juliet had been so great, Zeno thought, she hadn’t altogether absorbed the fact that her fiancé was a terribly changed man—and the changes weren’t likely to be exclusively physical.

Since Brett had returned to Carthage, and was living in his mother’s house about three miles from the Mayfields, Juliet had spent a good deal of time with him there; the elder Mayfields hadn’t seen much of him. When she could, Juliet accompanied Brett to the rehab clinic attached to the Carthage hospital; she attended some of his counseling sessions, as his fiancée; eagerly she reported back to her parents that as soon as he was better able to concentrate Brett intended to re-enroll at Plattsburgh and get a degree in business and that there was talk—(how substantial, Zeno didn’t know)—of Brett being hired by a Carthage businessman who made it a point to hire veterans.

See, Daddy—Brett has a future!

Though I know you want me to dump him. I will not.

Zeno would have protested, if Juliet had so accused him.

But, of course, Juliet had not.

Beautiful Juliet never accused anyone of such low thoughts. Least of all her father whom she adored.

But there came impish Cressida to slip her arm through Daddy’s arm and to tug at him, to murmur in his ear in her scratchy voice, “Poor Julie! Not the ‘war hero’ she’d expected, is he.” Cruel Cressida squirming with something like stifled laughter.

Zeno had said reprovingly, “Your sister loves Brett. That’s the main thing.”

Cressida snorted with laughter like a mischievous little girl.

“It is?”

Several nights later, on the Fourth of July, Juliet had returned home early—and alone—(the most gorgeous, gaudy fireworks had just begun exploding in the sky above Palisade Park)—to inform her family that the engagement was ended.

Her cheeks were tear-streaked. Her face had lost its luminosity and looked almost plain. Her voice was a hoarse whisper.

“We’ve both decided. It’s for the best. We love each other, but—it’s ended.”

Zeno and Arlette had been astounded. Zeno had felt a sick sinking sensation in his gut. For this was what he’d wanted—wasn’t it? His beautiful daughter spared a life with a handicapped and embittered husband?

When Arlette moved to embrace her, Juliet pushed past her with a choked little sob and hurried up the stairs and shut her bedroom door.

Even Cressida had been shocked. For once, her shiny black eyes hadn’t danced with derision when the subject of Juliet and Brett Kincaid came up—“Oh God! Julie will be so unhappy.”

At twenty-two, Juliet was still living at home. She’d gone to college in Oneida but had wanted to return to Carthage to teach (sixth grade) at the Convent Street School a few miles away from the family home on Cumberland Avenue. Planning her wedding to Corporal Brett Kincaid—guest list, caterer, bridal gown and bridesmaids, music, flowers, wedding service at the Congregationalist Church—had been the consuming passion of her life for the past eighteen months, and now that the engagement had ended Juliet seemed scarcely capable of speech apart from the most perfunctory exchanges with her family.

Though Juliet was always unfailingly courteous, and sweet. Tears welling in her eyes at which she brushed with her fingertips, as if apologetically.

There’d been no reproach in her manner, when the father gazed at her searchingly, waiting for her to speak. For never had Juliet so much as hinted Are you happy, Daddy? I hope you are happy, Brett is out of our lives.

Numbly Zeno said to Arlette: “She hasn’t spoken to you—yet? She hasn’t wanted to talk about it?”

“No.”

“What about Cressida?”

“No. Juliet would never discuss Brett with her.”

In the issue of the sisters, it had often been that Arlette clearly sided with the pretty one and not the smart one.

“Maybe Brett wanted to talk about it with Cressida. Maybe that was why—the reason—they were together last night . . .”

If truly they’d been together—alone together. Zeno had to wonder if that was true.

It was totally out of character for Cressida to go to a place like the Roebuck Inn. Totally unlike Cressida, particularly on a Saturday night. Yet witnesses had told investigating officers that they were sure they’d seen Cressida there the night before, in the company of several people—mostly men; and one of them Brett Kincaid.

Saturday night in midsummer, at Wolf’s Head Lake. There were a number of lakeside taverns of which the Roebuck was the oldest and the most popular, very likely the most crowded, and noisy; patrons spilled out of the inn and onto the decks overlooking the lake, and even down into the sprawling parking lot; on the deck was a local rock band, playing at a deafening volume. A drunken roar of motorboats on the lake, a drunken roar of motorcycles on Bear Valley Road.

Before he’d become a settled-down husband and father of two daughters, Zeno Mayfield had spent time at Wolf’s Head Lake. He knew the Roebuck taproom. He knew the Roebuck men’s rooms. He knew the sloshing of brackish water about the mossy posts sunk into the lake, that supported the Roebuck’s outdoor deck.

He knew the “scene” on a Saturday night.

How puzzling, that Cressida would go to such a place, voluntarily! His sensitive daughter who flinched hearing rock music on the radio and who disdained places like the Roebuck and anyone likely to patronize them.

“Most people are so crude. And so oblivious.”

Such pronouncements Zeno’s younger daughter had made from an early age. Her pinched little face pinched tighter with disdain.

Brett Kincaid acknowledged that he’d encountered Cressida at the lakeside inn. He’d acknowledged that she’d been in his Jeep. But he seemed to be saying that she hadn’t remained with him. His account of the previous night was incoherent and inconsistent. Asked about scratch-marks on his face and smears of blood on the front seat of his Jeep he’d given vague answers—he must have scratched his face somehow without knowing it, and the blood-smears on the seat were his. There were other items of “evidence” a deputy had found examining the vehicle that had been found with its front, right wheel in a ditch on the Sandhill Road on Sunday morning.

The bloodstains would be analyzed, to determine if the blood was Kincaid’s or someone else’s. (As part of a physical examination the previous year, Cressida had had blood work done by a local Carthage doctor; these records would be provided to police.)

Zeno had been told about the bloodstains in Kincaid’s Jeep that appeared to be “fresh” and “damp” and Zeno’s brain had seemed to clamp down. Arlette, too, had been told, and had gone silent.

For they knew—they knew—that Juliet’s fiancé, Juliet’s ex-fiancé, who’d come very close to being their son-in-law, wasn’t capable of hurting either of their daughters. They could not believe it, and would not.

As they could not believe that, at any minute, their missing daughter might not arrive home, burst into the house seeing an alarming number of vehicles parked outside—a mix of familiar faces and strangers in the living room—and cry: “What’s this? Who won the lottery?”

The father wanted to think: it might happen. However unlikely, it might happen.

“Oh Daddy, for God’s sake. You thought I was lost? You thought I was—killed or something?”

The daughter’s shrill laughter like ice being shaken.

THAT MORNING, Zeno had wanted to speak to Brett Kincaid.

Zeno had been told no. Not a good idea at this time.

“But just to—see him. For five minutes . . .”

No. Hal Pitney who was Zeno’s friend, a high-ranking officer in the Beechum County Sheriff’s Department, told him this was not a good idea at the present time and anyway not possible, since Kincaid was being interviewed by the sheriff McManus himself.

Not interrogated, which meant arrest. Only just interviewed, which meant the stage preceding a possible arrest.

I need to know from him just this: Is Cressida alive?

“ . . . only just to see him. Christ, he’s like one of the family—engaged to my daughter—my other daughter . . .”

Zeno stammered, trying to smile. Zeno Mayfield had long cultivated a wide flash of a smile, a politician’s smile, that came now unconsciously, with a look of being forced. He was frightened at the prospect of seeing Brett Kincaid, seeing how Brett regarded him.

Just tell me: is my daughter alive.

Pitney said he’d pass on the word to McManus. Pitney said it “wasn’t likely” that Zeno could speak face-to-face with Kincaid for a while but—“Who knows? It might end fast.”

“What? What ‘might end fast’?”

Into Pitney’s face came a wary look. As if he’d said too much.

“ ‘Custody.’ Him being in custody, and interviewed. It could end fast if he gives up all he knows.”

A chill passed into Zeno, hearing these words.

He knew, Hal Pitney had told him all he’d tell him right now.

Driving east of Carthage into the hilly countryside, into the foothills of the Adirondacks and into the Nautauga Preserve to join the search team that morning, Zeno had made a succession of calls on his cell phone trying to learn if there were “developments” in the interview with Brett Kincaid. Like a compulsive cell phone user who checks for new calls in his in-box every few minutes Zeno could not shut off the flat little phone, still less could he slide it into his shirt pocket and forget it. Several times he tried to speak with Bud McManus. For Zeno knew Bud, to a degree, enough, he’d thought, to merit special consideration. (In the scrimmage of Carthage politics, he’d done McManus a favor, at least once: hadn’t he? If not, Zeno regretted it now.) Instead, he wound up speaking with another deputy named Gerry Eisner who told him (confidentially) that the interview with Brett Kincaid wasn’t going well, so far—Kincaid claimed not to remember what had happened the night before, though he seemed to know that someone whom he alternately called “Cress’da” and “the girl” had been in his Jeep; at one point he seemed to be saying that “the girl” had left him and gotten into a vehicle with someone else whom he didn’t know—but he wasn’t sure of any of this, he’d been pretty much “wasted.”

Wasted. High school usage, guys boasting to one another of how sick-drunk they’d gotten on beer. Zeno trembled with indignation.

During the interview, Kincaid had seemed dazed, uncertain of his surroundings. He’d smelled strongly of vomit even after he’d been allowed to wash up. His eyes were bloodshot and his skin-grafted face made him look like “something freaky” in a horror movie, Eisner said.

You’d never guess, Eisner said, he’s only twenty-six years old.

You’d never guess he’d been a good-looking kid not so long ago.

“Jesus! A ‘war hero.’ ”

In Eisner’s voice Zeno detected a tone of wonderment, part-commiseration and part-revulsion.

It was pure chance that Corporal Kincaid had been apprehended that morning at approximately the time the Mayfields were making frantic calls about their missing daughter: taken into custody by a sheriff’s deputy at about 8 A.M. when he was found semiconscious, vomit- and blood-stained sprawled in the front seat of his Jeep Wrangler on Sandhill Road; the front, right wheel of the Jeep had gone off the unpaved road, that was elevated by about two feet above a marshy area. Early-morning hikers in the Preserve had called 911 on their cell phone to report the seemingly incapacitated vehicle with an “unresponding” man sprawled in the front seat and both front doors open.

When the deputy shook Kincaid awake, identifying himself as a law enforcement officer, Kincaid shoved and struck at him, shouting incoherently, as if he was frightened, and had no idea where he was—the deputy had had to overpower him, cuff him and call for backup.

Still, Kincaid hadn’t been arrested. Just brought to the Sheriff’s Department headquarters on Axel Road.

Zeno knew, Brett Kincaid wasn’t supposed to be drinking while taking medication. According to Juliet he was taking a half-dozen prescription pills daily.

Zeno knew, Brett Kincaid was “much changed” since he’d returned from Iraq. It was not a new or an uncommon situation—it should not have been, given media attention to similar disturbed, returning veterans, a surprising situation—but to those who knew Kincaid, to those who presumed to love him, it was new, it was uncommon, and it was disturbing.

Eisner said it did seem that Kincaid was maybe “brain damaged” in some way. For sure, Kincaid remembered something that had happened—he remembered a “girl”—but wasn’t sure what he remembered.

“You see that sometimes,” Eisner said. “In some instances.”

Zeno asked, what instances?

Eisner said, guardedly, “When they can’t remember.”

Zeno asked, can’t remember what?

Eisner was silent. In the background were men’s voices, incongruous laughter.

Zeno thought He thinks that Kincaid hurt her. Hurt her, blacked out and now doesn’t remember.

The father’s coolly-cruel legal mind considered: Insanity defense. Whatever he has done. Not guilty.

It was the first thought any defense lawyer would think. It was the most cynical yet the most profound thought in such a situation.

Yet, the father nudged himself: He was sure, his daughter had not really been hurt.

He felt a flood of guilt, chagrin: Of course, his daughter had not been hurt.

Sandhill Road was an unimproved dirt road that wound through the southern wedge of the Nautauga Preserve, following for much of its length the snaky curves of the Nautauga River. There were a few hiking trails here but along the river underbrush was dense, you would think impenetrable; yet there were faint paths leading down an incline to the river, that had to be at least ten feet deep at this point, fast-moving, with rippling frothy rapids amid large boulders. If a body were pushed into the river the body might be caught immediately in boulders and underbrush; or the body might be propelled rapidly downriver, leaving no trace.

It was perhaps a ten-minute drive from the Roebuck Inn at Wolf’s Head Lake to the entrance of the Nautauga Preserve and another ten-minute drive to Sandhill Point. Anyone who lived in the area—a boy like Brett Kincaid, for instance—would know the roads and trails in the southern part of the Preserve. He would know Sandhill Point, a long narrow peninsula jutting into the river, no more than three feet across at its widest point.

Outside the Preserve, Sandhill Road was quasi-paved and intersected with Bear Valley Road that connected, several miles to the west, with Wolf’s Head Lake and with the Roebuck Inn & Marina on the lake.

Sandhill Point was approximately eleven miles from 822 Cumberland Avenue which was the address of the Mayfields’ home.

Not too far, really—not too far for the daughter to make her way on foot if necessary.

If for instance—(the father’s mind flew forward like wings beating frantically against the wind)—she’d been made to feel ashamed, her clothes torn and dirty. If she had not wanted to be seen.

For Cressida was very self-conscious. Stricken with shyness at unpredictable times.

And—always losing her cell phone! Unlike Juliet who treasured her cell phone and would go nowhere without it.

Zeno was still on the phone with Eisner who was complaining about the local TV station issuing “breaking news” bulletins every half hour, putting pressure on the sheriff’s office to take time for interviews, come up with quotable quotes—“The usual bullshit. You think they’d be ashamed.”

Zeno said, “Yes. Right,” not sure what he was agreeing with; he had to ask, another time, if he could speak with Brett Kincaid who’d practically been his son-in-law, the fiancé of his daughter, please for just a minute when there was a break in the interview—“Just a minute, that’s all I would need”—and Eisner said, an edge of irritation in his voice, “Sorry, Zeno. I don’t think so.” For reasons that Zeno could appreciate, Eisner explained that no one could speak with Kincaid while he was in custody—(any suspect, any possible crime, he could call an accomplice, he could ask the accomplice to take away evidence, aid and abet him at a little distance)—except if Kincaid requested a lawyer he’d have been allowed that call but Kincaid had declined to call a lawyer saying emphatically he did not need or want a lawyer. Zeno thought with relief No lawyer! Good. Zeno could not imagine any Carthage lawyer whom Kincaid might call: in other, normal circumstances, the kid would have called him.

In a voice that had become grating and aggressive Zeno asked another time if he could speak with Bud McManus and Eisner said no, he did not think that Zeno could speak with Bud McManus but that, when there was news, McManus would call him personally. And Zeno said, “But when will that be? You’ve got him there, you’ve had him since, when—two hours at least—two hours you’ve had him—you can’t get him to talk, or you’re not trying to get him to talk—so when’s that going to be? I’m just asking.” And Eisner replied, words Zeno scarcely heard through the blood pounding in his ears. And Zeno said, raising his voice, fearing that the cell phone was breaking up as he approached the entrance to the Preserve, driving into the bumpy parking lot in his Land Rover, “Look, Gerry: I need to know. It’s hard for me to breathe even, without knowing. Because Kincaid must know. Kincaid might know. Kincaid would know—something. I just want to talk to Bud, or to the boy—if I could just talk to the boy, Gerry, I would know. I mean, he would tell me. If—if he has anything to tell—he would tell me. Because—I’ve tried to explain—Brett is almost one of the Mayfield family. He was almost my son. Son-in-law. Hell, that might happen yet. Engagements get broken, and engagements get made. They’re just kids. My daughter Juliet. You know—Juliet. And Cressida—her sister. If I could talk to Brett, maybe on the phone like this, not in person with other people around, at police headquarters, wherever you have him—just on the phone like this—I promise, I’d only keep him for two-three minutes—just want to hear his voice—just want to ask him—I believe he would tell me . . .”

The line was dead: the little cell phone had failed.

“DADDY.”

It was Juliet, tugging at his shoulder. For a moment he couldn’t recall where he was—which daughter this was. Then the sliver of fear entered his heart, the other girl was missing.

From Juliet’s somber manner, he understood that nothing had changed.

Yet, from her somber manner, he understood that there’d been no bad news.

“Sweetie. How are you.”

“Not so good, Daddy. Not right now.”

Juliet had roused him from a sleep like death. There was some reason for waking him, she was explaining, but through the roaring in his ears he was having difficulty hearing.

That beating pulse in the ears, the surge of blood.

Though his heart was beating slow now like a heavy bell rolling.

The girl should have leaned over him to kiss him. Brush his cheek with her cool lips. This should have happened.

“Be right down, honey. Tell your mother.”

She was deeply wounded, Zeno knew. What had passed between her sister and her former fiancé was a matter of the most lurid public speculation. Inevitably her name would appear in the media. Inevitably reporters would approach her.

It was 5:20 P.M. Good Christ he’d slept two and a half hours. The shame of it washed over him.

His daughter missing, and Mayfield asleep.

He hoped McManus and the others didn’t know. If for instance they’d tried to call him back, return his many calls, and Arlette had had to tell them her husband was sleeping in the middle of the day, exhausted. Her husband could not speak with them just now thank you.

This was ridiculous. Of course they hadn’t called.

He swung his legs off the bed. He pulled off his sweat-soaked T-shirt, underwear. Folds of clammy-pale flesh at his belly, thighs like hams. Steely-coppery hairs bristled on his chest and beneath his arms dense as underbrush in the Preserve.

He was a big man, not fat. Not fat yet.

Mischievous Cressida had had a habit of pinching her father at the waist. Uh-oh Dad-dy! What’s this.

It was a running joke in the Mayfield family, among the Mayfield relatives and Zeno’s close friends, that he was vain about his appearance. That he could be embarrassed, if it were pointed out that he’d put on weight.

Dad-dy better go on that Atkins diet. Raw steak and whiskey.

Cressida was petite, child-sized. Except for her frizzed hair like a dark aureole about her head you might mistake her for a twelve-year-old boy.

Arlette said disapprovingly: “Cressida won’t eat, because she ‘refuses’ to menstruate.”

The father was so shocked hearing this, he pretended he hadn’t heard.

A couple of months ago when Brett Kincaid had come to the house in loose-fitting khaki cutoffs Zeno had had a glimpse of the boy’s wasted thighs, flat stringy muscles atrophied from weeks of hospitalization. Remembering how Brett had looked a year before. It was shocking to see a young man no longer young.

Therapy was rebuilding the muscles but it was a slow and painful process.

Juliet helped him walk: had helped him walk.

Walk, walk, walk—for miles. Juliet’s slender arm around the corporal’s waist walking in Palisade Park where there were few hills. For hills left the corporal short of breath.

His arm- and shoulder-muscles were as they’d been before the injuries. When he’d been in a wheelchair at the VA hospital he’d wheeled himself everywhere he could, for exercise.

His skull had not been fractured in the explosion but his brain had been traumatized—“concussed.”

A hurt brain can heal. A hurt brain will heal.

It will take time. And love.

Juliet had said this. She was gripping her fiancé’s hand and her smile was fine and brave and without irony.

And so it had been a shock—a shock, and a relief—when only a few weeks later Juliet told them the engagement had ended.

Except, things don’t end so easily. The father knew.

Between men and women, not so easily.

Christ! Zeno smelled of his body. The sweat of anxiety, despair.

Before bed that night he would change the bedclothes himself, before Arlette came into the room—Zeno had a flamboyant way with bed-changing, whipping sheets into the air so that they floated, as a magician might; tucking in the corners, tight; smoothing out the wrinkles, deft, fast, zip-zip-zip he’d made his little daughters laugh, like a cartoon character. In Boy Scout camp he’d learned all sorts of handy tasks.

He’d been an Eagle Scout, of course. Zeno Mayfield at age fourteen, youngest Eagle Scout in the Adirondack region, ever.

He smiled, thinking of this. Then, ceased smiling.

He staggered into the bathroom. Flung on the shower, both faucets blasting. Leaning his head into the spraying water hoping to wake himself. Losing his balance and grabbing at the shower curtain but (thank God) not bringing it down.

The sheer pleasure of hot, stinging water cascading down his face, his body. For a moment Zeno was almost happy.

In the bathroom doorway Arlette stood—beyond the noise of the shower she was speaking to him, urgently—She’s been found! It’s over, our daughter has been found!—but when Zeno asked his wife to repeat her words she said, anxiously, “They’re here. The TV people. Come downstairs when you can.”

“Do I have time to shave?”

Arlette came to the shower, to peer at him. Arlette didn’t reach into the hot stinging water to draw her fingers across his stubbly jaws.

“Yes. I think you’d better.”

Quickly Zeno dried himself, with a massive towel. Tried to run a comb through his hair, took a hairbrush to it, hoping not to confront his reflection in the misty bathroom mirror, the bloodshot frightened eyes.

“Here. Here are fresh clothes. This shirt . . .”

Gratefully Zeno took the clothes from his wife.

Downstairs were uplifted voices. Arlette tried to tell him who was there, who’d just arrived, which relatives, which TV reporters, but Zeno wasn’t able to concentrate. He had an unnerving sense that his front door had been flung open, anyone could now enter.

The door flung open, his little girl had slipped out.

Except she wasn’t a little girl any longer of course. She was nineteen years old: a woman.

“How do I look? OK?”

It wasn’t unusual for Zeno Mayfield—being interviewed. TV cameras just made the interview experience more edgy, the stakes higher.

“Oh, Zeno. You cut yourself shaving. Didn’t you notice?”

Arlette gave a little sob of exasperation. With a wadded tissue she dabbed at Zeno’s jaw.

“Thanks, honey. I love you.”

Bravely they descended the stairs hand in hand. Zeno saw that Arlette had tied back her hair, that seemed to have lost its glossiness overnight; she’d dabbed lipstick on her mouth and had blindly reached into her jewelry box for something to lower around her neck—a strand of inexpensive pearls no one had seen her wear in a decade. Her fingers were icy-cold; her hand was trembling. Another time Zeno said, in a whisper, “I love you,” but Arlette was distracted.

And Zeno was disoriented, seeing so many people in his living room. And furniture had been moved aside in the room. TV lights were blinding. The female reporter for WCTG-TV was a woman whom Zeno knew from his mayoral days when Evvie Estes had worked in City Hall public relations in a cigarette-smoke-filled little cubicle office at the ground-floor rear of the old sandstone building. Evvie was older now, hard-eyed and hard-mouthed, heavily made-up, with an air of sincere-seeming breathless concern: “Mr. and Mrs. Mayfield—Zeno and Arlette—hello! What a terrible day this has been for you!”—thrusting the microphone at them as if her remark called for a response. Arlette was smiling tightly staring at the woman as if she’d been taken totally by surprise and Zeno frowned saying calmly and gravely, “Yes—a terribly anxious day. Our daughter Cressida is missing, we have reason to believe that she is lost in the Nautauga Preserve, or in the vicinity of the Preserve. She may be injured—otherwise she would have contacted us by now. She’s nineteen, unfortunately not an experienced hiker . . . We are hoping that someone may have seen her or have information about her.”

Zeno Mayfield’s public way of addressing interviewers, gazing into TV cameras with a little frowning squint of the brow, returned to him at even this strained moment. If there was a quaver in his voice, no one would detect it.

Evvie Estes, hair bleached a startling brassy-blond, asked several commonsense questions of the Mayfields. In his grave calm voice Zeno prevailed when Arlette showed no inclination to reply. Yes, their daughter had spoken with them on Saturday evening, before she’d gone out; no, they had not known that she was going to Wolf’s Head Lake—“But maybe Cressida hadn’t known she was going to the lake, when she left home. Maybe it was something that came up later.” Zeno wanted to think this, rather than that Cressida had lied to them.

But he couldn’t shake off the likelihood that Cressida had lied. She’d lied by omitting the truth. Saying she was going to a friend’s house, but not that, after visiting with her friend, she had plans to turn up at Wolf’s Head Lake nine miles away.

It had been established by this time that Cressida had remained with her friend Marcy until 10 P.M. at which time she’d left for “home”—as she’d led Marcy to think.

Cressida hadn’t driven to her friend’s house which was less than a mile from the Mayfields’ house, but walked. It was believed by Marcy that Cressida had then walked back home—having declined an offer of a ride from Marcy.

Or, it might have been that someone else, whose identity wasn’t known to Marcy, had picked Cressida up, when she’d left Marcy’s house on her way home.

Not all of this made sense (yet) to Zeno. None of this Zeno cared to lay bare before a TV audience.

Though he’d been thinking how ironic, when Cressida had been, as witnesses claimed, in the company of Brett Kincaid at Wolf’s Head Lake, her sister Juliet had been home with their parents; by then, Juliet had probably been in bed.

That night, the Mayfields had invited old friends for dinner and Juliet had helped prepare the meal with Arlette. And Cressida had made it a point to explain that she couldn’t come to dinner with them that night because she was seeing her high school friend Marcy Meyer.

Evvie Estes asked if there’d been anything to lead them to “suspect”—anything? When they’d last seen Cressida?

“No. It was an ordinary night. Cressida was seeing a friend from high school and she hadn’t had to tell us, we would have known, she’d have been back home by eleven P.M. at the latest. It was just—an ordinary night.”

Zeno hadn’t liked Evvie Estes pitching that word to them—“suspect.”

Zeno and Arlette were seated side by side on a sofa. Zeno clasped Arlette’s hand firmly in his as if to secure her. Earlier, Juliet had helped Arlette locate photographs of Cressida to provide to police and media people, to be shown on TV and posted online through the day; Zeno assumed that these photos would be shown on the 6 P.M. news, during the interview. And he hoped that the interview, which was being taped, about fifteen minutes in length, wouldn’t be drastically cut.

“All we can hope for is that Cressida will contact us soon—if she can. Or, if she’s been injured, or lost—that someone will discover her. We are praying that she is in the Preserve—that is, she hasn’t been—taken”—Zeno paused, blinking at the possibility, a sudden obstacle like an enormous boulder in his path—“taken somewhere else . . .” His old ease at public speaking was leaving him, like air leaking from a balloon. Almost, Zeno was stammering, as the interview ended: “If anyone can help us—help us find her—any information leading to her—her whereabouts—we are offering ten thousand dollars reward—for the recovery of—the return of—our daughter Cressida Mayfield.”

Arlette turned to stare at him. Ten thousand dollars!

This was entirely new. This had not been discussed. So far as Arlette knew, Zeno had not thought of a reward before this moment.

Uttering the words “ten thousand dollars” Zeno had spoken in a strangely elated voice. And he’d smiled strangely, squinting in the TV lights.

Soon then the interview ended. Zeno’s white shirt was sticking to his skin—he’d been sweating again. And now he, too, was trembling.

Of course the Mayfields could afford ten thousand dollars. Much more than this, they could afford if it meant bringing their missing daughter home.

“ZENO? WHERE ARE YOU GOING?”

“Back to the Preserve. To the search.”

“You are not! Not now.”

“There’s two hours of daylight, at least. I need to be there.”

“That’s ridiculous. You do not. Stay here with us . . .”

Zeno hesitated. But no no no no. He had no intention of remaining in this house, where he couldn’t breathe, waiting.