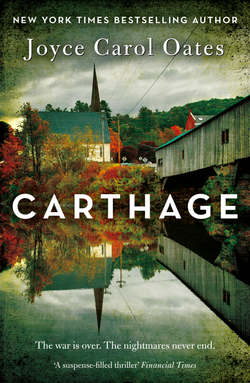

Читать книгу Carthage - Joyce Carol Oates - Страница 13

ОглавлениеFOUR

Descending and Ascending

I KNEW. AS SOON AS I saw her bed wasn’t slept-in.

I knew—something had happened.

AT 4:08 A.M. that Sunday morning Arlette awakened with a start.

The strangest sensation—that something was wrong, altered. Though in the shadowy interior of her bedroom—her and Zeno’s bedroom—here was comfort, ease. Though Zeno’s deep raspy rhythmic breathing was comfort to her, and ease.

Must’ve been a dream that wakened her. A swirl of anxiety like leaves spinning in a wind tunnel. She’d been pulled along—somewhere. Waking dry-mouthed and edgy believing that something was changed in the house or in the life of the house.

Or—one of her limbs was missing. That was the dream.

What was the phenomenon?—“phantom limb”? In that case an actual limb is missing from the body but you feel the (painful) presence of the (absent) limb; in this case, nothing was missing from Arlette’s body, so far as she knew.

It was mysterious to her, this loss. Yet it seemed unmistakable.

After this hour she would not ever feel otherwise.

WITHOUT WAKING ZENO she slipped from their bed.

Sometimes in the night when they awakened—through a single night, each woke several times, if but for a few seconds—Arlette kissed Zeno’s mouth in playful affection, or Zeno kissed hers. These were kisses like casual greetings—they were not kisses meant to wake the other fully.

How’s my sweet honey Zeno might mutter. But before Arlette could answer, Zeno would sink back into sleep.

Zeno was deeply asleep now. What subtle and irrevocable seismic shifting of the life of the house Arlette had sensed, Zeno was oblivious to. Like one who has fallen onto his back he lay spread-limbed, sprawled, taking up two-thirds of the bed in his warm thrumming sleep.

Arlette had learned to sleep beside her husband without being disturbed by him; whenever possible, her dreams incorporated his audible breathing in the most ingenious of ways.

Zeno’s snoring might be represented, for instance, by zigzag-shapes like metallic insects flying past the dreaming wife’s face. Sometimes, Arlette was awakened by her own surprised laughter.

That night, at dinner with friends, Zeno had consumed a bottle of wine himself, in the interstices of pouring wine for others. He’d been in very good spirits, telling stories, laughing loudly. He’d been tenderly solicitous of Juliet and refrained from teasing her, which was unlike the girls’ Daddy.

Through their long marriage there had been episodes—there had been interludes—of Zeno drinking too much. Arlette understood, Zeno had been drinking tonight because he felt guilty: for the relief he’d expressed when Juliet’s engagement had been broken.

Not to Juliet of course but to Arlette. Thank God. Now we can breathe again.

Except it wasn’t so easy. It would not be so easy. For their daughter’s heart had been broken.

Juliet had spent the evening with them. Instead of with her fiancé.

That is, her ex-fiancé.

Helping her mother prepare an elaborate meal in the kitchen, helping at the table, smiling, cheery. As if she hadn’t a life elsewhere, a life as a woman elsewhere, with a man, a lover from whom she’d been abruptly and mysteriously divided.

It was a small shock, to see the engagement ring (of which Juliet had been so proud) missing from Juliet’s finger.

In fact Juliet’s slender fingers were ring-less, as if in mourning.

At the dinner table, three couples and the daughter. Three middle-aged couples, a twenty-two-year-old daughter.

And the daughter so beautiful. And heartbroken.

Of course, no one had asked Juliet about Brett. No one had brought up the subject of Brett Kincaid at all. As if Corporal Kincaid didn’t exist, and he and Juliet had never been planning to be married.

It’s God-damned sad. But not our fault for Christ’s sake.

What did we do? Not a fucking thing.

He’d been drunk, muttering. Sitting heavily on the bed so the box springs creaked. Kicking a shoe halfway across the carpet.

Juliet should talk to us about it. We’re her God-damn parents!

When he was in one of his moods Arlette knew to leave him alone. She would not humor him, or placate him. She would leave him to steep in whatever mood rose in him like bile.

It was an asshole decision, to enlist in the army. “Serve his country”—see where it got him.

Anyway he won’t pull our daughter down with him.

Arlette didn’t stoop to retrieve the shoe. But she nudged it out of the way with her foot so that neither of them would stumble over it in the night, should one of them rise to go to the bathroom.

Immediately his head was lowered on the pillow, Zeno fell asleep.

A harsh serrated breathing, as if briars were caught in his throat.

The air-conditioning was on. A thin cool air moved through the bedroom. Arlette pulled a sheet up over her sleeping husband’s shoulders. At such moments she was overcome with a sensation of love for the man, commingled with fear, the sight of his thick-muscled shoulders, his upper arms covered in wiry hairs, the slack flesh of his jaws when he lay on his side. Inside the middle-aged man, the brash youthful Zeno Mayfield with whom Arlette had fallen in love yet resided.

In a man’s sleep, his mortality is most evident.

They were of an age now, and moving into a more emphatic age, when women began to lose their husbands—to become “widows.” Arlette could not allow herself to think in this way.

Remembering later, of that night: their concern had been for Juliet, and for Brett Kincaid whom possibly they would not ever see again.

Their thoughts were almost exclusively of Juliet. As it had been in the Mayfield household since Corporal Kincaid had returned in his disabled state.

Cressida passing like a wraith in their midst. On her way out for the evening to visit with a friend from high school who lived so close, Cressida could walk instead of driving. At about 6 P.M. she must have called out a casual good-bye—in the kitchen Arlette and Juliet would scarcely have taken note.

Bye! See you-all later.

Possibly, they hadn’t heard. Cressida hadn’t troubled to come to the kitchen doorway, to announce that she was going.

Zeno hadn’t been home. Out at the liquor store, choosing wine with the fussy particularity of a man who doesn’t know anything about wine really but would like to give the impression that he does.

It shouldn’t have been anything other than an ordinary evening though it was a Saturday night in midsummer.

In upstate New York in the Adirondack region, the population trebled in summer.

Summer people. Campers, pickup trucks. Bikers’ gangs. In the night, on even a quiet residential street like Cumberland, you could hear the sneering roar of motorcycles in the distance.

At the lakes—Wolf’s Head, Echo, Wild Forest—there were “incidents” each summer. Fights, assaults, break-ins, vandalism, arson, rapes, murders. Small local police departments with only a few officers had to call in the New York State Police, at desperate times.

When Zeno had been mayor of Carthage, several Hells Angels gangs had congregated in Palisade Park. After a day and part of a night of drunken and increasingly destructive festivities local residents had so bitterly complained, Zeno sent in the Carthage City Police to “peaceably” clear the park.

Just barely, a riot had been averted. Zeno had been credited with having made the right decisions, just in time.

No one had been arrested. No police officers had been injured. The state troopers hadn’t had to be summoned to Carthage.

The bikers’ gangs hadn’t returned to Palisade Park. But they congregated, weekends, at the lakes. Still you could sometimes hear, in the distance, at night, a window open, the sneering-defiant motorcycle-whine, mixed with a sound of nighttime insects.

Arlette left the bedroom. Zeno hadn’t wakened.

In a thin muslin nightgown in bare feet making her way along the carpeted corridor. Past the shut door of Juliet’s room—for she knew, Juliet was home—Juliet had been in bed for hours, like her parents—unerringly to the room in which she knew there was something wrong.

By this time, past 4 A.M., Cressida would have returned from Marcy Meyer’s house. Hours ago, she’d have returned. She wouldn’t have wanted to disturb her parents but would have gone upstairs to her room as quietly as possible—it was a peculiarity of their younger daughter, since she’d been a small child, as Zeno noted she could creep like a little mousie and no one knew she was there.

Even as Arlette was telling herself this, she was pushing open the door, switching on a light, to see: Cressida’s bed still made, undisturbed.

This was wrong. This was very wrong.

Arlette stood in the doorway, staring.

Of course, the room was empty. Cressida was nowhere in sight.

They’d gone to bed after their guests left and the kitchen was reasonably clean. They’d gone to bed soon after 11 P.M., Arlette and Zeno, without a thought, or not much more than a fleeting thought, about Cressida who was, after all—as they’d been led to believe—only just visiting with her high school friend Marcy Meyer less than a mile away.

Maybe the girls had had dinner together. Or maybe with Marcy’s parents. Maybe a DVD afterward. Misfit girls together in solidarity Cressida had joked.

In high school, Cressida and Marcy had been “best friends” by default, as Cressida said. Friendships of girls unpopular together are forged for life.

(It was Cressida’s way to exaggerate. Neither she nor Marcy Meyer was “unpopular”—Arlette was certain.)

Slowly Arlette came forward, to touch the comforter on Cressida’s bed.

With perfect symmetry the comforter had been pulled over the bedclothes. If Arlette were to lift it she knew she would see the sheets beneath neatly smoothed, for Cressida could not tolerate wrinkles or creases in fabrics.

The sheets would be tightly tucked in between the mattress and the box springs.

For it was their younger daughter’s way to do things neatly. With an air of fierce disdain, dislike—yet neatly.

All things that were tasks and chores—“household” things—Cressida resented having to do. Her imagination was loftier, more abstract.

Yet, though she resented such tasks, she dispatched them swiftly, to get them out of the way.

Can’t imagine anything more stultifying than the life of a housewife! Poor Mom.

Arlette was frequently nettled by her younger daughter’s thoughtless remarks. Though she knew that Cressida loved her, at times it seemed clear that Cressida did not respect her.

But if you hadn’t been up for it, Jule and I wouldn’t be here, I guess.

So, thanks!

Arlette wondered: was it possible that Cressida had planned to stay overnight at Marcy’s? As she’d done sometimes when the girls were in middle school together. It seemed unlikely now, but . . .

For God’s sake, Mom. What an utterly brainless idea.

Arlette left Cressida’s room and went downstairs. She was breathing quickly now though her heartbeat was calm.

From a wall phone in the kitchen downstairs, Arlette called Cressida’s cell phone number.

There came a faint ringing, but no answer.

Then, a burst of electronic music, dissonant chords and computer-voice coolly instructing the caller to leave a message after the beep.

Cressida? It’s Mom. I’m calling at four-ten A.M. Wondering where you are . . . If you can please call back as soon as possible . . .

Arlette hung up the phone. But immediately, Arlette lifted the receiver and called again.

The second time, she fumbled leaving a message. Just Mom again. We’re a little worried about you, honey. It’s pretty late . . . Give us a call, OK?

Now invoking us. For Cressida did respect her father.

It occurred to Arlette then that Cressida might be home: only just not in her room.

From earliest childhood she’d been an unpredictable child. You might look for her in all the wrong places as she watched you through a crack in a doorway, bursting into laughter at the worried look in your face.

Especially, Cressida had thought scrunched-up (adult) faces were funny.

So Arlette checked the downstairs rooms of the house: the TV room in the basement, which Cressida didn’t often occupy, objecting that it was partially underground and, in very wet weather, wriggly little centipedes appeared on the (Sears, slate-colored, slightly stained) wall-to-wall carpeting to her extreme disgust; Zeno’s cluttered home-office, with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves crammed with far more than just books, and an ancient rolltop desk Zeno liked to boast had been inherited from a Revolutionary War “quasi-ancestor” when in fact he’d bought it at an estate auction: a room in which, when she’d been a moody high school student, Cressida had sometimes holed herself away in when Zeno wasn’t there; and nooks and crannies of the living room which was a long narrow room with a beamed oak ceiling, shadow-splotched even when lighted, with a gleaming black baby-grand Steinway piano which, sadly, to Arlette’s way of thinking, no one played any longer, since Cressida had abruptly quit piano lessons at the age of sixteen.

But why quit, honey? You play so well . . .

Sure. For Beechum County.

No one. Nothing. In none of these rooms.

But then, Arlette hadn’t really expected to discover Cressida sleeping anywhere except in her bed.

At the rear sliding-glass door, which opened out onto a flagstone terrace in need of a vigorous weed-trimming, Arlette leaned outside to breathe in the muggy night air. Her eyes lifted to the night sky—a maze of constellations the names of which she could never recall as Cressida could even as a small child brightly reciting the names as if she’d been born knowing them: Andromeda. Gemini. Big Dipper. Little Dipper. Virgo. Pegasus. Orion . . .

Arlette stepped out onto the redwood deck. Just to check the outdoor furniture—and Zeno’s sagging hammock strung between two sturdy trees—but no Cressida of course.

Went to the garage, entering by a side door. Switched on the garage light—no one inside the garage of course.

Barefoot, wincing, Arlette went to check each of the household vehicles—Zeno’s Land Rover, Arlette’s Toyota station wagon, Juliet’s Skylark. Of course, there was no one sleeping or hiding in any of these.

Making her way then out the asphalt driveway which was a lengthy driveway to the street—Cumberland Avenue. Though Cumberland was one of Carthage’s most prestigious residential streets, in the high, hilly northern edge of town abutting the old historic cemetery of the First Episcopal Church of Carthage, Arlette might as well have been facing an abyss—there were no streetlights on and no lights in their neighbors’ houses. Only a smoldering-dull light seemed to descend from the sky as if a bright moon were trapped behind clouds.

It was possible—so desperation urged the mother to think—that Cressida had made arrangements to meet someone after she’d spent the evening at Marcy’s; they might now be together, in a vehicle parked at the curb, talking together, or . . .

How many times Arlette had sat with boys in their vehicles, in front of her parents’ house, talking together, kissing and touching . . .

But Cressida wasn’t that kind of girl. Cressida didn’t “go out” with boys. At least not so far as her family knew.

I worry that Cressida is lonely. I don’t think she’s very happy.

Don’t be ridiculous! Cressida is one-of-a-kind. She doesn’t give a damn for what other girls care for, she’s special.

So Zeno wished to believe. Arlette was less certain.

She did guess that it was a painful thing, to be the smart one following in the trail of the pretty one.

In any case there was no vehicle parked at the end of the Mayfields’ long driveway. Cressida was nowhere on the property, it was painfully obvious.

With less regard for her bare feet, Arlette returned quickly to the house, to the kitchen where the overhead light shone brightly. You would not think it was 4:30 A.M.! The pumpkin-colored Formica counters were freshly wiped and the dishwasher was still warm from having been set into motion at about 10:30 P.M.; with her usual cheery efficiency Juliet had helped Arlette clean up after the dinner party. Together in the kitchen, in the aftermath of a pleasant evening with old friends, an evening that would come to acquire, in Arlette’s memory, the distinction of being the last such evening of her life, Arlette might have spoken with Juliet about Brett Kincaid—but Juliet did not seem to invite such an intimacy.

Nor did either Arlette or Juliet speak of Cressida—at that time, what was there to say?

Just going over to Marcy’s, Mom. I can walk.

Don’t wait up for me OK?

Arlette lifted the phone receiver another time and called Cressida’s cell phone number even as she prepared herself for no answer.

“Maybe she lost the phone. Maybe someone stole it.”

Cressida was careless with cell phones. She’d lost at least two, both gifts from Zeno who wanted his daughters to be within calling-range, if he required them. And he wanted his daughters to have cell phones in case of emergency.

Was this an emergency? Arlette didn’t want to think so.

She returned to Cressida’s room—walking more slowly now, as if she were suddenly very tired.

No one. An empty room.

And now she saw how neatly—how tightly—books were inserted into the bookcases that, by Cressida’s request, Zeno had had a carpenter build into three of the room’s walls so that it had looked—almost—as if Cressida were imprisoned by books.

Some were children’s books, outsized, with colorful covers. Cressida had loved these books of her early childhood, that had helped her to read at a very young age.

And there were Cressida’s notebooks—also large, from an art-supply store in Carthage—in which, as a brightly imaginative young child, she’d drawn fantastical stories with Crayolas of every hue.

Initially, Cressida hadn’t objected when her parents showed her drawings to relatives, friends and neighbors who were impressed by them—or more than impressed, astonished at the little girl’s “artistic talent”—but then, abruptly at about age nine Cressida became self-conscious, and refused to allow Zeno to boast about her as he’d liked to do.

It had been years since Cressida’s brightly colored fantastical-animal drawings had been tacked to a wall of her room. Arlette missed these, that revealed a childish whimsy and playfulness not always evident in the precocious little girl with whom she lived—who called her, with a curious stiffness of her mouth, as if the word were utterly incomprehensible to her—“Mom.”

(No problem with Cressida saying “Daddy”—“Dad-dy”—with a radiant smile.)

For the past several years there had been, on Cressida’s wall, pen-and-ink drawings on stiff white construction paper in the mode of the twentieth-century Dutch artist M. C. Escher who’d been one of Cressida’s abiding passions in high school. These drawings Arlette tried to admire—they were elaborate, ingenious, finely drawn, resembling more visual riddles than works of art meant to engage a viewer. The largest and most ambitious, titled Descending and Ascending, was mounted on cardboard, measuring about three feet by three feet: an appropriation of Escher’s famous lithograph Ascending and Descending in which monk-like figures ascended and descended never-ending staircases in a surreal structure in which there appeared to be several sources of gravity. Cressida’s drawing was of a subtly distorted family house with walls stripped away, revealing many more staircases than there were in the house, at unnatural—“orthogonal”—angles to one another; on these staircases, human figures walked “up” even as other human figures walked “down” on the underside of the same steps.

Gazing at the pen-and-ink drawing, you became disoriented—dizzy. For what was up was also down, simultaneously.

Cressida had worked at her Escher-drawings obsessively, for at least a year, at the age of sixteen. Mysteriously she’d said that M. C. Escher had held up a mirror to her soul.

The figures in Descending and Ascending were both valiant and pathetic. Earnestly they walked “up”—earnestly they walked “down.” They appeared to be oblivious of one another, stepping on reverse steps. Cressida’s variant of the Escher drawing was more realistic than the original—the structure containing the inverted staircases was recognizable as the Mayfields’ sprawling old Colonial house, furniture and wall hangings were recognizable, and the figures were clearly the Mayfields—tall sturdy shock-haired Daddy, Mom with a placid smiling vacuous face, gorgeous Juliet with exaggerated eyes and lips and inky-frizzy-haired Cressida a fierce-frowning child with arms and legs like sticks, half the height of the other figures, a gnome in their midst.

The Mayfield figures were repeated several times, with a comical effect; earnestness, repeated, suggests idiocy. Arlette never looked at Descending and Ascending and Cressida’s other Escher-drawings on the wall without a little shudder of apprehension.

It was easier for Cressida to mock than to admire. Easier for Cressida to detach herself from others, than to attempt to attach herself.

For she’d been hurt, Arlette had to suppose. In ninth grade when Cressida had volunteered to teach in a program called Math Literacy—(in fact, this program had been initiated by Zeno’s mayoral administration in the face of state budget cuts to education)—and after several enthusiastic weekly sessions with middle-school students from “deprived” backgrounds she’d returned home saying with a shamefaced little frown that she wasn’t going back.

Zeno had asked why. Arlette had asked why.

“It was a stupid idea. That’s why.”

Zeno had been surprised and disappointed with Cressida when she refused to explain why she was quitting the program. But Arlette knew there had to be a particular reason and that this reason had to do with her daughter’s pride.

Arlette recalled that something unfortunate had happened in high school, too, related to Cressida’s Escher-fixation. But she’d never known the details.

On Cressida’s desk, which consisted of a wide, smooth-sanded plank and aluminum drawers, put together by Cressida herself, was a laptop (closed), a notebook (closed), small stacks of books and papers. All were neatly arranged as if with a ruler.

Arlette rarely entered her younger daughter’s room except if Cressida was inside, and expressly invited her. She dreaded the accusation of snooping.

It was 4:36 A.M. Too soon after her last attempt to call Cressida’s cell phone for Arlette to call her again.

Instead, she went to Juliet’s room which was next-door.

“Mom?”—Juliet sat up in bed, startled.

“Oh, honey—I’m sorry to wake you . . .”

“No, I’ve been awake. Is something wrong?”

“Cressida isn’t home.”

“Cressida isn’t home!”

It was an exclamation of surprise, not alarm. For Cressida had not ever stayed out so late—so far as her family knew.

“She was at Marcy’s. She should have been home hours ago.”

“I’ve tried her cell phone. But I haven’t called Marcy—I suppose I should.”

“What time is it? God.”

“I didn’t want to disturb them, at such an hour . . .”

Juliet rose from bed, quickly. Since breaking with Brett Kincaid she was often home and in bed early, like a convalescent; but she slept only intermittently, for a few hours, and spent the rest of the night-hours reading, writing emails, surfing the Internet. On her nightstand beside her laptop were several library books—Arlette saw the title Republic of Fear: The Inside Story of Saddam’s Iraq.

They tried to recall: what had Cressida called out to them, when she’d left the house? Nothing out of the ordinary, each was sure.

“She walked to Marcy’s. She must have walked home, then—or . . .”

Arlette’s voice trailed off. Now that Juliet had been drawn into her concern for Cressida, she was becoming more anxious.

“Maybe she’s staying over with Marcy . . .”

“But—she’d have called us, wouldn’t she . . .”

“ . . . she’d never stay overnight there, why on earth? Of course she’d have come home.”

“But she isn’t home.”

“Did you look anywhere other than her room? I know it isn’t likely, but . . .”

“I didn’t want to wake Zeno, you know how excitable he is . . .”

“You called her cell—you said? Should we try again?”

Nighttime cream Juliet wore on her face, on her beautifully soft skin, shone now like oozing oil. Her hair, a fair brown, layered, feathery, was flattened on one side of her head. Between the sisters was an old, unresolved rivalry: the younger’s efforts to thwart and undermine the older’s efforts to be good.

Juliet called her sister from her own cell phone. Again there was no answer.

“I suppose we should call Marcy. But . . .”

“I’d better wake Zeno. He’ll know what to do.”

Arlette entered the darkened bedroom, where Zeno was sleeping. She shook his shoulder, gently. “Zeno? I’m sorry to wake you, but—Cressida isn’t home.”

Zeno’s eyelids fluttered open. There was something touching, vulnerable and poignant in Zeno waking from sleep—he put Arlette in mind of a slumbering bear, perilously wakened from a winter doze.

“It’s going on five A.M. She hasn’t been home all night. I’ve tried to call her, and I’ve looked everywhere in the house . . .”

Zeno sat up. Zeno swung his legs out of bed. Zeno rubbed his eyes, ran his fingers through his tufted hair.

“Well—she’s nineteen years old. She doesn’t have a curfew and she doesn’t have to report to us.”

“But—she was only just going to Marcy’s for dinner. She walked.”

Walked. Now that Arlette had said this, for the second time, a chill came over her.

“ . . . she was walking, at night, alone . . . Maybe someone . . .”

“Don’t catastrophize, Lettie. Please.”

“But—she was alone. I think she must have been alone. We’d better call Marcy.”

Zeno rose from bed with surprising agility. In boxer shorts he wore as pajamas, bristly-haired, flabby in the torso and midriff, he padded barefoot to the bureau, to snatch up his cell phone.

“We’ve tried to call her, Zeno. Juliet and me . . .”

Zeno paid her no heed. He made the call, listened intently, broke the connection and called immediately again.

“She doesn’t answer. Maybe she’s lost the phone. I’m just so terribly worried, if she was walking back home . . . It’s Saturday night, someone might have been driving by . . .”

“I said, Lettie, please—don’t catastrophize. That isn’t helpful.”

Zeno spoke sharply, irritably. He was stepping into a pair of rumpled khaki shorts he’d thrown onto a chair earlier that day.

In Zeno, emotion was justified: in others in his family, it was apt to be excessive. Particularly, Zeno countered his wife’s occasional alarm by classifying it as catastrophizing, hysterical.

Downstairs, the lighted kitchen awaited them like a stage set. Zeno looked up the Meyers’ number in the directory and called it as Arlette and Juliet stood by.

“Hello? Marcy? This is Zeno—Cressida’s father. Sorry to bother you at this hour, but . . .”

Arlette listened eagerly and with mounting dread.

Zeno questioned Marcy for several minutes. Before he hung up, Arlette asked to speak to her. There was little that Arlette could add to what Zeno had said but she needed to hear Marcy’s voice, hoping to be reassured by Marcy’s voice; her daughter’s friend was a sturdy freckle-faced girl enrolled in the nursing school at Plattsburgh, long a fixture in Cressida’s life though no longer the close friend she’d been a few years previously.

But Marcy could only repeat that at about 10:30 P.M.—after they’d had dinner with her mother and her (elderly, ailing) grandmother—and watched a DVD—Cressida had left to return home as she’d planned, on foot.

“I offered to drive her, but Cressida said no. I did think that I should drive her because it was late, and she was alone, but—you know Cressida. How stubborn she can be . . .”

“Do you have any idea where else she might have gone? After visiting with you?”

“No, Mrs. Mayfield. I guess I don’t.”

Mrs. Mayfield. As if Marcy were a high school student, still.

“Did she mention anyone to you? Did she call anyone?”

“I don’t think so . . .”

“You’re sure she didn’t call anyone, on her cell phone?”

“Well, I—I don’t think so. I mean—I know Cressida pretty well, Mrs. Mayfield—who’d she call? If it wasn’t one of you?”

“But where on earth could she be, at almost five A.M.!”

Arlette spoke sharply. She was angry with Marcy Meyer for allowing her daughter to walk home on a Saturday night: though the distance was only a few blocks, part of the walk would have been on North Fork Street, which was well traveled after dark, near an intersection with a state highway; and she was angry with Marcy Meyer for protesting, in an aggrieved child’s voice Who’d she call, if it wasn’t one of you?

THE RAPIDLY SHRINKING REMNANT of the night-before-dawn in the Mayfields’ house had acquired an air of desperation.

Now dressed, hastily and carelessly, Zeno and Arlette drove in Zeno’s Land Rover to the Meyers’ house on Fremont Street, a half-mile away.

Freemont was a hillside street, narrow and poorly paved; houses here were crowded together virtually like row houses, of aged brick and loosened mortar. Arlette had remembered being concerned, when Cressida and Marcy Meyer first became friends, in grade school, that her outspoken and often heedless daughter might say something unintentionally wounding about the size of the Meyers’ house, or the attractiveness of its interior; she’d been surprised enough at the blunt, frank, teasing-taunting way in which Cressida spoke to Marcy, who was a reticent, stoic girl lacking Cressida’s quick wit and any instinct to defend herself or tease Cressida in turn. Cressida had drawn comic strips in which a short dark-frizzy-haired girl with a dour face and a tall stocky freckled girl with a cheery face had comical adventures in school—these had seemed innocent enough, meant to amuse and not ridicule.

Once, Arlette had reprimanded Cressida for saying something rudely witty to Marcy, while Arlette was driving the girls to an event at their school, and Marcy said, laughing, “It’s OK, Mrs. Mayfield. Cressie can’t help it.”

As if her daughter were a scorpion, or a viper—Can’t help it.

Yet it had been touching, the girl called Cressida “Cressie.” And Cressida hadn’t objected.

At the Meyers’ house, Zeno wanted to go inside and speak with Marcy and her mother; Arlette begged him not to.

“They won’t know anything more than Marcy has told us. It isn’t seven A.M. You’ll just upset them. Please, Zeno.”

Slowly Zeno drove along Fremont Street, glancing from side to side at the facades of houses. All seemed blind, impassive at this early hour of the morning; many shades were drawn.

At the foot of Fremont, Zeno turned the Land Rover around in a driveway and drove slowly back uphill. Passing the Meyers’ house, he was now retracing the probable route Cressida had taken, walking home.

Both Zeno and Arlette were staring hard. How like a film this was, a documentary! Something had happened, but—in which house? And what had happened?

House after house of no particular distinction except they were houses Cressida had passed, on her way to Marcy Meyer’s, and on her way from Marcy Meyer’s, the night before. There, at a corner, a landmark lightning-scorched oak tree, at the intersection with North Fork; a block farther, at Cumberland Avenue, at the ridge of the hill, the large impressive red-brick Episcopal church and the churchyard beside and behind it. Both the church and the churchyard were “historical landmarks” dating to the 1780s.

Cressida would have passed by the church, and the churchyard. On which side of the street would she have walked?—Arlette wondered.

Zeno made a sound—grunt, half-sob—mutter—as he braked the Land Rover and without explanation climbed out.

Zeno entered the churchyard, walking quickly. He was a tall disheveled man with a stubbly chin who carried himself with an aggressive sort of confidence. He’d thrown on a soiled T-shirt and khaki shorts and on his sockless feet were grubby running shoes. By the time Arlette hurried to join him he’d made his way to the end of the first row of aged markers, worn so thin by weather and time that the names and dates of the dead were unreadable.

Beyond the churchyard was a no-man’s-land of underbrush and trees, owned by the township.

The churchyard smelled of mown grass, not fresh, slightly rotted, sour. The air was muggy and dense, in unpredictable places, with gnats.

“Zeno, what are you looking for? Oh, Zeno.”

Arlette was frightened now. Zeno remained turned away from her. The most warmly gregarious of men, the most sociable of human beings, yet Zeno Mayfield was remote at times, and even hostile; if you touched him, he might throw off your hand. He prided himself as a man among men—a man who knew much that happened in the world, in Carthage and vicinity, that a woman like Arlette didn’t know; much that never made its way into print or onto TV. He was looking now, in a methodical way that horrified Arlette, for the body of their daughter—could that be possible?—in the tall grasses at the edge of the cemetery; behind larger grave markers; behind a storage shed where there was an untidy pile of grass cuttings, tree debris, and discarded desiccated flowers. Horribly, with a clinical sort of curiosity, Zeno stooped to peer inside, or beneath, this pile—Arlette had a vision of a girl’s broken body, her arms outstretched among the broken tree limbs.

“Zeno, come back! Zeno, come home. Maybe Cressida is home now.”

Zeno ignored her. Possibly, Zeno didn’t hear her.

Arlette waited in the Land Rover for Zeno to return to her. She started the ignition, and turned on the radio. Waiting for the 7 A.M. news.

“SHE’S SOMEWHERE, OBVIOUSLY. We just don’t know where.”

And, as if Arlette had been contesting this fact: “She’s nineteen. She’s an adult. She doesn’t have a curfew in this house and she doesn’t have to report to us.”

While Zeno and Arlette made calls on the land phone, Juliet made calls on her cell phone. Initially to relatives, whom it didn’t seem terribly rude to awaken at such an early hour with queries about Cressida; then, after 7:30 A.M., to neighbors, friends—including even girls in Cressida’s class whom Cressida probably hadn’t seen since graduation thirteen months before.

(Juliet said: “Cressida will be furious if she finds out. She will think we’ve betrayed her.” Arlette said: “Cressida doesn’t have to know. We can always call back and tell them—not to tell her.”)

Juliet had a vast circle of friends, both female and male, and she began to call them—on the phone her voice was warmly friendly and betrayed no sign of worry or anxiety; she didn’t want to alarm anyone needlessly, and she had a fear of initiating a firestorm of gossip. She took her cell phone outside, standing on the front walk as she made calls; peering out at Cumberland Avenue, watching for Cressida to come home. Afterward she would say I was so certain. I could not have been more certain if Jesus Himself had promised me, Cressida was on her way home.

One of the calls Juliet made was to a friend named Caroline Skolnik who was to have been a bridesmaid in Juliet’s wedding. And Juliet told Caroline that her sister Cressida hadn’t come home the night before, and they were worried about her, and Juliet was wondering if Caroline knew anything, or had any ideas; and to Juliet’s astonishment Caroline said hesitantly she’d seen Cressida the night before, or someone who looked very much like Cressida, at the Roebuck Inn at Wolf’s Head Lake.

Juliet was so astonished, she nearly dropped her cell phone.

Cressida at the Roebuck Inn? At Wolf’s Head Lake?

Caroline said that she’d been there with her fiancé Artie Petko and another couple but they hadn’t stayed long. The Roebuck Inn had used to be a nice place but lately bikers had been taking it over on weekends—Adirondack Hells Angels. There was a rock band comprised of local kids people liked, but the music was deafening, and the place was jammed—“Just too much happening.”

Inside the tavern, there’d been a gang of guys they knew and a few girls in several booths. The air had been thick with smoke. Caroline was surprised to see Brett there—“He wasn’t with any girl, just with his friends,” Caroline said quickly, “but there were girls kind of hanging out with them. Brett was looking—he wasn’t looking—maybe it was the light in the place, but Brett was looking—all right. The surgery he’s had—I think it has helped a lot. And he had dark glasses on. And—anyway—there came Cressida—I think it was Cressida—just out of nowhere we happened to see her, and she didn’t see us—she seemed to have just come into the taproom, alone—in all that crowd, and having to push her way through—she’s so small—I don’t think there was anyone with her, unless maybe she’d come with someone, a couple—it wasn’t clear who was with who. Cressida was wearing those black jeans she always wears, and a black T-shirt, and what looked like a little striped cotton sweater; it was a surprise to see her, Artie and I both thought so, Artie said he’d never seen your sister in anyplace like the Roebuck, not ever. He knows your dad, he was saying, ‘Is that Zeno Mayfield’s daughter? The one that’s so smart?’ and I said, ‘God, I hope not. What’s she doing here?’ Brett was in a booth with Rod Halifax, and Jimmy Weisbeck, and that asshole Duane Stumpf, and they were pretty drunk; and there was Cressida, talking with Brett, or trying to talk with Brett; but things got so crowded, and kind of out of control, so we decided to leave. So I don’t actually know—I mean, I don’t know for sure—if it was your sister, Juliet. But I think it had to be, there’s nobody quite like Cressida.”

Juliet asked what time this had been.

Caroline said about 11:30 P.M. Because they’d left and gone to the Echo Lake Tavern and stayed there for about forty minutes and were home by 1 A.M.

“Oh God, Juliet—you’re saying Cressida hasn’t come home? She isn’t home? You don’t know where she is? I’m so sorry we didn’t go over to talk to her—maybe she needed a ride home—maybe she got stranded there. But we thought, well—she must’ve come with someone. And there was Brett, and she knows him, and he knows her—so, we thought, maybe . . .”

Slowly Juliet entered the house. Arlette saw her just inside the doorway. In her face was a strange, stricken expression, as if something too large for her skull had been forced inside it.

“What is it, Juliet? Have you heard—something?”

“Yes. I think so. I think I’ve heard—something.”

FOLLOWING THIS, things happened swiftly.

Zeno called Brett Kincaid’s cell phone number—no answer.

Zeno called a number listed in the Carthage directory for Kincaid, E.—no answer.

Zeno climbed into his Land Rover and drove to Ethel Kincaid’s house on Potsdam Street, another hillside street beyond Fremont: a two-storey wood frame with a peeling-beige facade, set close to the curb, where Ethel Kincaid in a soiled kimono answered the door to his repeated knocking with a look of alarmed astonishment.

“Is he home? Where is he?”

Fumbling at the front of the kimono, which shone with a cheap lurid light as if fluorescent, Ethel peered at Zeno cautiously.

“I—don’t know . . . I guess n-not, his Jeep isn’t in the driveway . . .”

Between Zeno Mayfield and Ethel Kincaid there was a layered sort of history—vague, vaguely resentful (on Ethel’s part: for Zeno Mayfield, when he’d been mayor of Carthage and nominally Ethel Kincaid’s boss, had not ever seemed to remember her name when he encountered her) and vaguely guilty (on Zeno’s part: for he understood that he’d snubbed this plain fierce-glaring woman whom life had mysteriously disappointed). And now, the breakup of Zeno’s daughter and Ethel’s son lay between them like wreckage.

“Do you have any idea where Brett is?”

“N-No . . .”

“Do you know where he went last night?”

“No . . .”

“Or with who?”

Ethel Kincaid regarded Zeno, his disheveled clothing, his metallic-stubbly jaws and swampy eyes that were both pleading and threatening, with a defiant sort of alarm. She had the just discernibly battered look of a woman well versed in the wayward emotions of men and in the need to position herself out of the range of a man’s sudden lunging grasp.

“I’m afraid I don’t know, Mr. Mayfield. Brett’s friends don’t come to the house, he goes to them. I think he goes to them.”

Mr. Mayfield was uttered with a pointless sort of spite. Surely they were social equals, or had been, when Zeno’s daughter had become engaged to Ethel’s son.

Zeno remembered Arlette remarking that Brett’s mother was so unfriendly. Even Juliet who rarely spoke of others in a critical manner murmured of her fiancé’s mother She is not naturally warmhearted or easy to get to know. But—we will try!

Poor Juliet had tried, and failed.

Arlette had tried, and failed.

“Ethel, I’m sorry to disturb you at such an early hour. I tried to call, but there was no answer. It’s crucial that I speak with Brett—or at least know where I can find him. This isn’t about Juliet, incidentally—it involves my daughter Cressida.” Zeno was making it a point to speak slowly and clearly and without any suggestion of the pent-up fury he felt for this unhelpful woman who’d taken a step back from him, clutching at the front of her rumpled kimono as if fearing he might snatch it open. “We’ve been told that they were together for a while last night—at the Roebuck Inn. And Cressida hasn’t come home all night, and we don’t know where she is. And we think—your son might know.”

Ethel Kincaid was shaking her head. A tangle of graying dirty-blond hair, falling to her shoulders, uncombed. A smell as of dried sweat and talcum powder wafting from her soft loose fleshy body inside her clothing.

Now a look of apprehension came into her face. And cunning.

Ethel shook her head emphatically no—“I don’t know anything that my son does.”

“Could I see his room, please?”

“His room? You want to see his—room? In this house?”

“Yes. Please.”

“But—why?”

Zeno had no idea why. The impulse had come to him, desperately; he could not retreat without attempting something.

Ethel was looking confused now. She was a woman in her mid-fifties whom life had used negligently—her skin was sallow, her eyelashes and eyebrows so scanty as to be near-invisible, her mouth was a sullen smudge. She took another step back into the dimly lighted hall of the house as if the glare in Zeno Mayfield’s face was such, she shrank from it. Stammering she said he couldn’t come inside, that wasn’t a good idea, and she had to say good-bye to him now, she had to close the door now, she could not speak to him any longer.

“Ethel—wait! Just let me see Brett’s room. Maybe—there will be something there, that will help me . . .”

“No. That isn’t a good idea. I’m going to close the door now.”

“Ethel, please. I’m sure there is some explanation for this, but—at the moment—Arlette and I are terribly worried. And we’ve been told that Brett was seen with her, last night. It can’t be a coincidence, your son and my daughter . . .”

“If you don’t have a warrant, Mr. Mayfield, I don’t have to let you in.”

“A warrant? I’m not a police officer, Ethel. Don’t be ridiculous. I’m not even a city official any longer. I just want to see Brett’s room, just for a minute. How can you possibly object to that?”

“No. I can’t. Brett wouldn’t want that—he hates all of you.”

Ethel Kincaid was about to shut the door in Zeno’s face but he pressed the palm of his hand against it, holding it open. A pulse beat wildly in his forehead. He could not believe what Ethel Kincaid had so heedlessly uttered but he would never forget it.

Hates all of you. You.

“If your son has hurt my daughter—my daughter Cressida—if anything has happened to Cressida—I will kill him.”

Ethel Kincaid threw her weight against the door, to shut it. And Zeno released the door.

He was stunned. He could not think clearly. He knew, he had better return to the Land Rover and drive home before he did something irrevocable like pounding violently on the God-damned door that had been shut rudely in his face.

Like breaking into the Kincaid house.

The spiteful woman would call 911, he knew. Give her the slightest pretext, she would fuck up Zeno Mayfield and his family all she could.

He returned to the Land Rover, that had been parked crookedly at the curb. He saw that a seat belt trailed out from the driver’s seat, like something broken, discarded. A swift vision came to him of the pile of debris in the Episcopal churchyard. Driving away from the Kincaid house without a backward glance he thought Maybe she didn’t hear me. Maybe she won’t remember.

IN THE DRIVEWAY Arlette stood waiting for Zeno to return.

Waiting to see if he was bringing their daughter home with him.

And so in her face, as Zeno climbed out of the Land Rover, he saw the disappointment.

“She wasn’t there?”

“No.”

“Did you talk to—Ethel? Was Brett there?”

“Ethel was no help. Brett wasn’t there.”

Arlette hurried to keep up with Zeno, who was headed into the house.

Suddenly it had become 8:20 A.M. So swiftly, the night had passed into dawn and now into a sunny and shimmering-hot morning.

The privacy of the night. The exposure of the morning.

Arlette asked, in a shaky voice, “Do you think that Cressida and Brett might have gone away together?—or, he took her somewhere? To hurt her? To embarrass us? Zeno?”

“Cressida is nineteen. She’s an adult. If she chooses to stay away overnight, that’s her prerogative.”

Zeno spoke harshly, ironically. He had not the slightest faith in what he was saying but he believed these words must be reiterated.

Arlette clutched at his arm. Arlette’s fingers dug into his arm.

“But—if she didn’t choose? If someone has hurt her? Taken her? We have to help our daughter, Zeno. She has no one but us.”

Unspoken between them was the thought She isn’t really an adult. She is a child. For all her pose of maturity, a child.

There was no choice now, no postponing the call, even as Zeno stood in the driveway staring with eyes that felt seared, ravaged with such futile staring in the direction of Cumberland Avenue as into an abyss out of which at any moment—(feasibly! Not illogically and not impossibly!—for as a young aggressive attorney Zeno Mayfield had often conjured the attractive possibilities of alternate universes in which alternate narratives revealed his [guilty] clients to be “innocent” of the charges that had been brought against them)—his daughter Cressida might appear; no choice, he knew, except to contact law enforcement; calling the Beechum County Sheriff’s Department and asking to speak to Hal Pitney who was a lieutenant on the force, not a close friend of Zeno Mayfield’s but an old friend from Zeno’s political days and, he wanted to think, a reliable friend. With forced calmness he told Hal that he knew, it might seem premature to be reporting his daughter missing, since Cressida was nineteen, and not a child, but the circumstances seemed to warrant it: she’d been gone overnight, she was definitely not a person to behave irresponsibly; they had learned that she’d been seen at the Roebuck Inn the previous night, alone; then, later, in the company of several men of whom one was Brett Kincaid. (Pitney surely knew of Corporal Brett Kincaid, from stories in the local media.) Zeno said they’d called Cressida’s cell phone repeatedly and they’d called virtually everyone in Carthage who knew her, or might know of her—she seemed to have vanished.

Zeno said he’d gone to Kincaid’s house. And Kincaid was missing, too.

Zeno spoke rapidly and, he hoped, persuasively. He was not prepared for Hal Pitney telling him that, though they knew nothing about his daughter, it had happened that Brett Kincaid had been brought into headquarters that morning, less than an hour before. He’d been reported by hikers seemingly incapacitated in his Jeep Wrangler, that appeared to have skidded partway off the Sandhill Road, just inside the Nautauga Preserve. There’d been no one with him but there’d been “bloody scratch or bite marks” on his face and bloodstains in the front seat of his vehicle; he’d been “agitated” and “belligerent” and tried to fight the deputy who restrained him, cuffed him and brought him into headquarters.

“He isn’t cooperating. He’s pretty much out of it. Hungover, and sick to his stomach, and scared. He didn’t seem to know where he was, or why, or if anyone, like a girl, had been with him. We’ve sent two deputies back to investigate the scene, and his Jeep. We’re questioning him now. You’d better come to headquarters, Zeno. You and your wife. And bring photographs of your daughter—the more recent, the better.”

This news was so utterly unexpected, Zeno had to stagger into the house to fumble for a chair, a kitchen chair, and sit down, heavily; he felt as if he’d been kicked in the gut, the air slammed out of him. So weak, so frightened, he was scarcely able to hear Arlette pleading with him—“Zeno, what is it? Have they found her? Is she—alive? Zeno?”

Time moved now in zigzag leaps.

Once Zeno made this call. Once what had been a private concern became irreversibly public.

Once their daughter was publicly designated missing.

Once they’d brought photographs of the missing daughter to law enforcement officers, to be shared with the media, broadcast over TV and on the Internet and printed in newspapers.

Once they’d described her. Once they’d described her in all ways they believed to be crucial to finding her.

Then, time passed with dazzling swiftness even as, perversely, time passed with excruciating slowness.

Swift because too much was crammed into too small a space. Swift like a nightmare film run at a high speed for a cruel-comic effect.

Slow because for all that was happening very little that was crucial seemed to be happening.

Slow because despite the many calls they were to receive in the course of a day, two days, several days, a week, the call they awaited, that Cressida had been found, did not come.

Alive and well. We have found your daughter—alive and well.

This call, so desperately wished-for, did not come.

(AND THEY KNEW, each hour that their daughter was missing there was more likelihood that she’d been injured, or worse.)

(Each hour that Brett Kincaid refused to cooperate, or was unable to cooperate, there was more likelihood that she’d been injured, or worse, and less likelihood that she would be found.)

PROVIDING LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS with photographs of Cressida.

Spreading a half-dozen photos across a table.

Startling to see their daughter gazing up at them.

Wariness in Cressida’s eyes, thin-lashed dark eyes gleaming with irony and the faintest tincture of resentment as if she’d known that strangers would be staring at her, memorizing her face, without her permission.

In none of the photos was Cressida smiling. Not since childhood had Cressida been recorded smiling.

Arlette had wanted to explain—Our daughter was not an unhappy person. But she refused to smile when she was photographed. Not even in her high school yearbook is she pictured smiling. And this is because . . .

But Arlette could not utter these words. Her throat closed, she could not.

. . . she’d said, you know that one of the pictures will be for the obituary. So you can’t ever smile. You’d be a fool to smile at your own funeral.

IN THE LATE MORNING of Sunday, July 10, 2005, the search for the missing girl in the Nautauga Preserve began and continued until searchers were obliged to leave the park, at dusk; it was continued the next morning, until dusk; and the next morning, until dusk.

The search differed considerably from more routine searches in the vast Preserve for lost hikers, campers, mountain climbers, numbering quite a few in the course of an average summer: for it was believed that this missing girl might have been assaulted—raped, killed?—by a man.

The search was complicated by the possibility that the missing girl had been dumped into the Nautauga River, and her body carried far downstream.

Yet, morale was high. Especially among those volunteer searchers who knew Cressida Mayfield and the (younger, female) park rangers who were determined to find the girl, missing in their own territory.

It had been eleven years since anyone had been lost in the Preserve and had not been found alive; in that case, involving a young boy believed to have run away from home, in the winter, the boy’s body wasn’t found until the following spring.

In the course of the search a miscellany of castaway items was found—rotted and desiccated articles of clothing including underwear (both men’s and women’s); single gloves, mittens; single shoes, hiking boots, and belts; mangled hats; plastic bottles, cans, and Styrofoam; maps of the Preserve, hiking books, bird books, children’s toys, a single headless doll terrifying to the volunteer searcher who discovered it believing it to be, for a moment, a headless human infant.

Also, scattered bones determined to be the bones of animals or birds.

Here and there, a dead, rotting animal carcass like the partially devoured doe discovered by Zeno Mayfield, that seemed to have caused the father of the missing girl to collapse in a paroxysm of exhaustion and despair.

God if I could trade my life for hers. If that were possible . . .

SO MANY VEHICLES parked in the Mayfields’ driveway, and along Cumberland Avenue, if the missing girl had arrived home she’d have thought it was a festive occasion.

Muttering out of the side of her mouth, a droll remark her mother could almost hear—What’s the big deal? Juliet’s getting engaged—again?

Bright TV camera lights in the living room as Arlette and Zeno Mayfield of Cumberland Avenue, Carthage, parents of the missing girl, were being interviewed by local TV personality Evvie Estes for WCTG-TV 6 P.M. news.

Arlette hadn’t been able to speak. Zeno had done all the talking.

Of course, Zeno Mayfield was very good at talking.

His voice had quavered only slightly. His eyes pouched in tiredness were damp and seemed to have no clear focus.

But he’d showered, and shaved, and put on clean pressed clothes, and his thick-tufted hair had been brushed properly. He knew to speak to the TV audience by way of the TV interviewer and he knew not to be nettled or discomfited by certain of the woman’s questions.

Arlette gripped in her right fist a wadded tissue. Her tongue had gone numb. Her eyes were fixed to the rapacious eyes of the heavily made-up Evvie Estes. Her terror was, her nose would begin to run, her eyes would leak tears, unsparingly illuminated in the bright TV lights.

Our daughter. Our Cressida. If anyone has any information leading to . . .

Then, there came the surprise of the ten-thousand-dollar reward.

Not one of the law enforcement officers who’d been interviewing the Mayfields had known this was coming. Judging by her confusion on camera, Arlette had not known this was coming. Zeno spoke in an impassioned voice of a ten-thousand-dollar reward for information leading to the recovery of—the return of—our daughter Cressida.

SURPRISING NEWS—A REWARD.

Not a great idea.

Many more calls will come in.

Many more calls will come in.

FOR INSTANCE, from “witnesses” who’d sighted the missing girl, they were sure: in and near and not-so-near the Nautauga Preserve.

As far north as Massena, New York. As far south as Binghamton.

In a 7-Eleven. Hitchhiking. In the passenger seat of a van headed south on I-80.

Wearing a baseball cap pulled low on her forehead.

Wearing sunglasses.

Coming out of the Onondaga CineMax on Route 33, with a bearded man—the movie was The War of the Worlds with Tom Cruise.

As far north as Massena, New York. As far south as Binghamton.

Dozens of calls. In time, hundreds.

Most valuable were calls from “witnesses” claiming to have been at the Roebuck Inn on the night of Saturday, July 9.

Guys who knew Corporal Kincaid by sight. Women who’d seen a girl they suspected to be, or believed to be, or knew to be Cressida Mayfield, at the inn: in the crowded taproom, on the deck overlooking the lake, in the women’s room “sick to her stomach”—“splashing water on her face.”

One of the bartenders, who knew Kincaid and his friends Halifax, Weisbeck, Stumpf—“The girl came in from somewhere. Like she was alone, and kind of scared-looking. In jeans, a black T-shirt, and some kind of top, or sweater. Not the kind of girl who turns up at the Roebuck on Saturday night. Maybe she was with Kincaid, or just ran into him. I think they left together. Or—all of them left together. It was a pretty loud scene, with the band on the deck. But definitely, it wasn’t any bikers she was with—this girl ‘Cressida.’ Hey—if other people call about Kincaid, and it turns out it’s him, like if the girl is hurt—do we split the ten thousand dollars? What’s the deal?”

And there was an ex-girlfriend of Rod Halifax, named Natalie Cantor, claiming to have been a “friend” of Juliet Mayfield’s in high school, who called Zeno Mayfield’s office phone to tell him in an incensed, just perceptibly slurred voice that whatever happened to his daughter, Rod and his buddies would know—“Once, the bastard got me drunk, slipped some drug into a drink, he’d been wanting to break up with me and was acting really nasty trying to pimp me to his disgusting buddies—Jimmy Weisbeck, that asshole Stumpf—out in his pickup. Right out in the parking lot, the son of a bitch. They’re all mean drunks. I don’t know Kincaid, but I know Juliet. I know your daughter, she’s an angel. I’m not joking, she’s an angel. Juliet Mayfield is an angel. I don’t know the other one—‘Cress’da.’ I never saw ‘Cress’da.’ Anything you want to know about that poor girl, Rod Halifax will know. I wasn’t the first girl he got tired of, and treated like shit. It was not ‘consensual’—it was God-damn fucking rape. And I was sick afterward, I mean—infected. So, ask him. Arrest him, and ask him. Anything that’s happened to that poor girl, like if they raped her, and strangled her, and dumped her body in the lake—you can be sure Rod Halifax was responsible.”

ZIGZAG TIME ENTERED her head: hours moved slow as sludge while days flew past on drunken-careening wings.

Until she could think A week. This Sunday is a week. And she hasn’t been found and it would have the ring of tentative good news: She hasn’t been found in some terrible place.

He would never forgive himself, she knew.

Though it could not be his fault. Yet.

Arlette had long gotten over being jealous—at any rate, showing her jealousy—of her daughters. Particularly Zeno adored Juliet but he’d also been weak-minded about Cressida, the “difficult” daughter—the one whom it was a challenge to love.

At the very start, the little girls had adored their mother. As babies, their young mother was all to them. Which is only natural of course.

But quickly then, Daddy had stolen their hearts. Big burly bright-faced Daddy who was so funny, and so unpredictable—Daddy who loved to subvert Mommy’s dictums and upset, as he liked to joke, Mommy’s apple cart.

As if an orderly household—eating at mealtimes, and properly at a table, with others—walking and not running/rushing on the stairs—keeping your bedroom reasonably clean, and not messing up a bathroom for others—were a silly-Mommy’s apple cart to be overturned for laughs.

But Mommy knew to laugh, when she was laughed-at.

Mommy knew it was love. A kind of love.

Except it hurt sometimes—the father siding with the daughter, in mockery of her.

(Not Juliet of course: Juliet never mocked anyone.)

(Mockery came too easily to Cressida. As if she feared a softer emotion would make her vulnerable.)

Arlette knew: if something terrible had happened to Cressida, Zeno would blame himself. Though there could be no reason, no logical reason, he would blame himself.

Already he was saying to whoever would listen I wasn’t even there, when she left. God!

In a voice of wonder, self-reproach Maybe she’d have told me—something. Maybe she’d have wanted to talk.

COUNTLESS TIMES they’d gone over Saturday evening: when Cressida had left the house, on her way to the Meyers’ for dinner.

Casually, you might say indifferently calling out to her mother and her sister in the kitchen—Bye! See you later.

Or even, though this was less likely given that Cressida wouldn’t have stayed very late at Marcy’s—Don’t wake up for me.

(Had Cressida said that? Don’t wake up for me?—intentionally or otherwise? Wake up not wait up. That was Cressida’s sort of quirky humor. Suddenly, Arlette wondered if it might mean something.)

(Snatching at straws, this was. Pathetic!)

Certainly it was ridiculous for Zeno to reproach himself with not having been home at that time. As if somehow—(but how?)—he might have foreseen that Cressida wouldn’t be returning when she’d planned, and when they’d expected her?

Ridiculous but how like the father.

Particularly, the father of daughters.

EACH TIME the phone rang!

Several phones in the Mayfield household: the family line, Zeno’s cell, Arlette’s cell, Juliet’s cell.

Always a kick of the heart, fumbling to answer a call.

Deliberately Arlette avoided seeing the caller ID in the hope that the caller would be Cressida.

Or, that the caller would be a stranger, a law enforcement officer, possibly a woman, in Arlette’s fantasizing it was a woman, with the good news Mrs. Mayfield!—we’ve found your daughter and she wants to talk to you.

Beyond this, though Arlette listened eagerly, there was—nothing.

As if, in the strain of awaiting the call, and hearing Cressida’s voice, she’d forgotten what that voice was.

DRIVING TO THE BANK, fumbling with the radio dial, in a panic to hear the “top of the hour” news—almost colliding with a sanitation truck.

Recovering, and, in the next block, almost colliding with an SUV whose driver tapped his horn irritably at her.

And, in the bank, bright-faced and smiling in the (desperate, transparent) hope of deflecting looks of pity, waiting in line at a teller’s window exactly as she’d have waited if her daughter was not missing.

This fact confounded her. This fact seemed to mock her.

Wanting to hide. Hide her face. But of course, no.

“Arlette? You are Arlette Mayfield—aren’t you? I’m so sorry—really really sorry—about your daughter . . . We’ve told our kids, one is a junior in high school, the other is just in seventh grade, if they hear anything—anything at all—to tell us right away. Kids know so much more than their parents these days. Out at the lake, and in the Preserve, there’s all kinds of things going on—under-age drinking is the least of it. All kinds of drugs including ‘crystal meth’—kids don’t know what they’re taking, they’re too young to realize how dangerous it is . . . I don’t mean that your daughter was with any kind of a drug-crowd, I don’t mean that at all—but the Roebuck Inn, that’s a place they hang out—there’s these Hells Angels bikers who are known drug-dealers—but parents have their heads in the sand, just don’t want to acknowledge there’s a serious—tragic—problem in Carthage . . .”

And not in the bank parking lot, can’t let herself cry. Not with bank customers trailing in and out. And anyone who knew Arlette Mayfield, including now individuals not-known to her who’d seen her on WCTG-TV with her husband Zeno pleading for the return of their daughter, could stare through her car windshield and observe and carry away the tale to all who would listen with thrilled widened eyes That poor woman! Arlette Mayfield! You know, the mother of the missing girl . . .

CALLS CONTINUED TO COME to police headquarters.

Though peaking on the second day, Monday, July 11: a record number of calls following the front-page article, with photos, in the Carthage Post-Journal. And the notice of the ten-thousand-dollar reward.

Myriad “witnesses” claiming to have sighted Cressida Mayfield—somewhere. Or to have knowledge of what might have happened to her and where she was now.

In some cases, making veiled accusations against people—(neighbors, relatives, ex-husbands)—who might have “kidnapped” or “done something to” Cressida Mayfield.

Zeno had wanted these calls routed through him. It was his fear that a valuable call would be overlooked by someone in the sheriff’s office.

Detectives explained to Zeno that, where reward money is involved, a flood of calls can be expected, virtually all of them worthless.

Yet, though likely to be worthless, the calls have to be considered—the “leads” have to be investigated.

The Beechum County Sheriff’s Department was understaffed. The Carthage PD was helping in the investigation though this department was even smaller.

If kidnapping were suspected, the FBI might be contacted. The New York State Police.

Was offering a reward so publicly a mistake? Zeno didn’t want to think so.

“Maybe the mistake is not offering enough. Let’s double it—twenty thousand dollars.”

“Oh, Zeno—are you sure?”

“Of course I’m sure. We have to do something.”

“Maybe you should speak with Bud McManus? Or maybe—”

“She’s our daughter, not his. Twenty thousand will attract more attention. We have to do something.”

Arlette thought But if there is nothing? If we can do nothing?

There was Zeno on the phone. Defiant Zeno on two phones at once: the family phone, and his cell phone.

“Hello? This is Zeno Mayfield. We’ve decided to double the reward money to twenty thousand dollars. Yes—right. Twenty thousand dollars for information leading to the recovery and return of our daughter Cressida Mayfield. Callers will be granted anonymity if they wish.”

IN CRESSIDA’S ROOM. Drifting upstairs in the large empty-echoing house as if drawn to that room.

Where, if she’d been home, and in the room, Cressida would have been surprised to see her parents and possibly not pleased.

Hey, Dad. Mom. What brings you here?

Not snooping—are you?

“Her bed wasn’t slept-in. That was the first thing I saw.”

Arlette spoke in a hoarse whisper. They might have been crouched in a mausoleum, the room was so dimly lighted, so stark and still.

In the center of the room Zeno stood, staring. It was quite possible, Arlette thought, that he hadn’t entered their daughter’s room in years.

Detectives had asked Arlette if anything was “missing” from the room. Arlette didn’t think so, but how could Arlette know: their daughter’s life was a very private life, only partially and, it sometimes seemed, grudgingly shared with her mother.

Detectives had searched the room, as Arlette and Zeno stood anxiously by. As soon as the detectives were finished with any part of the room—the closet, the old cherrywood chest of drawers Cressida had had since she was six years old—Arlette hurried to reclaim it, and re-establish order.

With latex-gloved hands they’d placed certain articles of clothing in plastic bags. They’d taken a not-very-clean hairbrush, a toothbrush, other intimate items for DNA purposes presumably.

Cressida’s laptop. They’d asked permission to open it, to examine it, and the Mayfields had said yes, of course.

Though reluctant even to open the laptop themselves. To peer into their daughter’s private life, how intrusive this was! How Cressida would resent it.

The detectives had taken it away with them, and left a receipt.

Almost Arlette thought I hope they return it before Cressida comes back.

Almost Arlette thought, unforgivably, I hope Cressida doesn’t come back before they return it.

Zeno said, falsely hearty: “It’s good that you woke up, Lettie. That something woke you. Thank God you came in here when you did.”

“Yes. Something woke me . . .”

That sensation of a part of the house missing. A part of her body missing. Phantom limb.

Arlette’s thought was, seeing the room through Zeno’s eyes, that it didn’t have the features of a girl’s room, as a man might imagine them.

Cressida’s clothes were all put away and out of sight—neatly folded in drawers, on shelves, hanging in closets. And her small stubby-looking shoes, neatly paired, on the floor of the closet.

One of the detectives, meaning to be kind, had remarked that his teenaged daughter’s room looked nothing like this one.

Zeno had tried to explain, their daughter had never been a teenager.

Years ago Cressida had cast away the soft bright colors and fuzzy fabrics of girlhood and replaced them with the stark black-and-white geometrical designs and slick surfaces of M. C. Escher, that so strangely entranced her. She had so little interest in colors—(her jeans were mostly black, her shirts, T-shirts, sweaters)—Arlette could wonder if she saw colors at all; or, seeing, thought them sentimental, softhearted.

Zeno was peering at the labyrinthine Descending and Ascending as if he’d never seen it before. As if it might provide a clue to his daughter’s disappearance.

Did he recognize himself in the drawing?—Arlette wondered. Or were the miniature humanoid-figures too distorted, caricatured?

Zeno’s eye was for the large, blatant, blinding. Zeno had not a shrewd eye for the miniature.

Arlette slid her arm through her husband’s. Since Sunday, she was always touching him, holding him. Very still Zeno would stand at such times, not exactly responding but not stiffening either. For he dared not give in to the rawest emotion, she knew. Not quite yet.

“Whatever happened, with Cressida’s math teacher, Zeno? Remember? When she was in tenth grade? She never told me . . .”

“ ‘Rickard.’ He was her geometry teacher.”

Arlette recalled days, it might have been weeks, of veiled exchanges between Zeno and Cressida, about something that had happened, or hadn’t happened in the right way, at school. It might have been that Cressida had brought a portfolio of drawings to school—beyond that, Arlette hadn’t known.

When she’d asked Cressida what was troubling her, Cressida had told her it was none of her business; when she’d asked Zeno, he’d told her, apologetically, that it was up to Cressida—“If she wants to tell you, she will.”

Their alliance was to each other, Arlette thought.

She’d hated them, then. In just that moment.

She’d asked Juliet, out of desperation. But Juliet who wasn’t living at home at the time—who was a freshman at the State University at Oneida—had soared so far beyond her tenth-grade sister, she’d had little interest in the sister’s emotional crises—“Some teacher who didn’t appreciate her enough, I think. You know Cressida!”

Arlette didn’t, though. That was the problem.

Zeno said hesitantly, as if even now he were reluctant to violate any confidence of their daughter’s, that when Cressida had first become so interested in M. C. Escher she’d created a portfolio of pen-and-ink drawings using numerals and geometrical figures, in imitation of Escher’s lithographs.

“This one—Metamorphoses”—Zeno indicated one of the pen-and-ink drawings displayed on Cressida’s wall—“was the first one I’d seen, I think. I didn’t know what the hell to make of it, initially.” Arlette examined the drawing: it was smaller than Descending and Ascending and seemingly less ambitious: moving from left to right, human figures morphed into mannequins, then geometrical figures; then numerals, then abstract molecular designs; then back to human figures again. As the figures passed through the metamorphoses from left to right their “whiteness” shaded into “darkness”—like negatives; then, as negatives, as they passed through reverse stages of metamorphoses, they became “white” again. And some of the scenes were set on Carthage bridges, with reflections in the water that underwent metamorphoses, too.

“It’s based upon an Escher drawing of course. But how skillfully it’s executed! I remember looking at it, Metamorphoses, following with my eyes the changes in the figures, back and forth . . . It was the first time I realized, I think, that our daughter was so special. You can’t imagine Juliet doing anything like this.”

“Juliet wouldn’t want to do anything quite like this.”

“Of course. That’s my point.”

“Cressida’s drawings are like riddles. I’ve always thought it was too bad, her art is so ‘difficult.’ Remember when she was a little girl, not four years old, she drew such wonderful animals and birds with crayons. Everyone adored them. I’d always thought I might work with her, I’d thought we could create children’s books together. But . . .”

“Lettie, come on! Cressida isn’t interested in ‘children’s books’—not now, and not then. Her talent is for something more demanding.”

“But she seems to have quit doing art. There’s nothing new on the wall here, that I can see.”

“She didn’t take art courses at St. Lawrence. She said she didn’t respect the teachers. She didn’t think she could learn anything from them.”

How like Cressida! Yet she didn’t seem to have made her way otherwise.

Arlette asked what had happened with Mr. Rickard?

From time to time Arlette encountered the rabbity moustached Vance Rickard on the street in Carthage, or at the mall. Though Arlette smiled at him, and would have greeted him warmly, the high school math teacher invariably turned away without seeming to see her, frowning.

“That bastard! He’d seen some of Cressida’s drawings in her notebook, and praised her; he said he was an admirer of Escher, too. So Cressida put together a portfolio of her new work and brought it to school to show him, and the son of a bitch wounded her by saying, ‘Not bad. Pretty good, in fact. But you must be original. Escher did this first, so why copy him?’ Cressida was devastated.”

Arlette could well understand, their sensitive daughter would be devastated by such a heartless remark.

Yet, she’d wanted to ask Cressida something like this herself.

“He might have meant well. It was just—thoughtless . . . I’m sorry that Cressida was so upset.”

“That was why she did so poorly in geometry that semester. She stayed away from class, she was so ashamed. She’d ended with a barely passing grade.”

Arlette remembered: that turbulent season in their daughter’s life.

“Cressida came to me and told me what he’d said. She was utterly demolished. She said, ‘I can’t go back. I hate him. Get him fired, Daddy.’ I was furious, too. I made an appointment to speak with Rickard who professed to be totally unaware of what he’d said, or even if he’d said it; he told me that if he’d made such a remark to Cressida it must have been meant playfully. He said he’d been impressed with her drawings and with her work in his class though he worried that she was ‘inconsistent’—‘too easily discouraged.’ ”

Arlette thought yes, that is so. But Zeno was still indignant.

“I wouldn’t have tried to get the bastard fired, of course. Even if—maybe—I could have. The man was just crude, and thoughtless. Cressida changed her mind, too: ‘Maybe we should just forget about it, Daddy. I wish we would. I don’t deserve any higher grade than the one I got, really.’ But that was ridiculous, she’d certainly have earned an A, if the damned Escher misunderstanding hadn’t happened.”

Zeno didn’t need to add: Cressida’s grade-point average would have been considerably higher without a D+ in sophomore math.

For often it happened that Cressida did well in her high school courses through a semester and then, unaccountably, as if to spite her own pretensions of excellence, she failed to complete the course, or failed to study for the final exam, or even to take the final exam. She was often ill—respiratory ailments, nausea, migraine headaches. Her high school record was a zigzag fever chart that culminated in her senior year when, instead of graduating as class valedictorian, as the teachers who admired her observed to her parents, she graduated thirtieth in a class of one hundred sixteen—a dismal record for such a bright girl. Instead of being accepted at Cornell, as she’d hoped, she was fortunate to have been accepted at St. Lawrence University.

Her first year away from home, in the small college town of Canton, Cressida had been homesick, lonely; a girl who’d scorned conventional “clichéd” behavior, yet she’d found herself missing her home, the routine and safety of her home. Still, she hadn’t emailed or called her parents often and when Arlette tried to contact her, Cressida was elusive; if Arlette managed to get her to answer her cell phone, Cressida was remote, taciturn.

“Honey, is something wrong? Can you tell me? Please?” Arlette had pleaded, and Cressida had made a sound that was the verbal equivalent of a shrug. “You aren’t having trouble with your courses, are you?” Arlette asked, and Cressida said coldly, no. “Then what is it? Can’t you tell me?” Arlette asked, and Cressida said, mimicking her, “ ‘What is’—what?” Arlette had been reading about suicidally depressed undergraduates, and Cressida’s reaction worried her. (When she mentioned the subject to Zeno he’d laughed at her. “Lettie! You never fail to catastrophize.” When she’d seen a TV documentary on suicide among adolescents, in which the word epidemic was used, she dared not mention it to Zeno.)