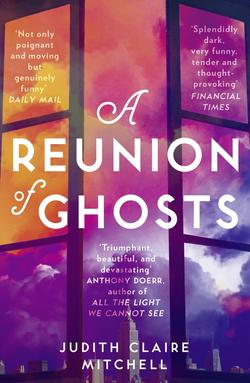

Читать книгу A Reunion of Ghosts - Judith Mitchell Claire - Страница 10

CHAPTER 1

ОглавлениеFrom a distance the tattoo wrapped around Delph’s calf looks like a serpentine chain, but stand closer and it’s actually sixty-seven tiny letters and symbols that form a sentence—a curse:

the sins of the fathers are visited upon the children to the 3rd & 4th generations

We are that fourth generation: Lady, Vee, and Delph Alter, three sisters who share the same Riverside Drive apartment in which they were raised; three women of a certain age, those ages being, on this first day of summer 1999, forty-nine, forty-six, and forty-two. We’re also seven fewer Jews than a minyan make, a trio of fierce believers in all sorts of mysterious forces that we don’t understand, and a triumvirate of feminists who nevertheless describe ourselves in relation to relationships: we’re a partnerless, childless, even petless sorority consisting of one divorcee (Lady), one perpetually grieving widow (Vee), and one spinster—that would be Delph.

When we were young women, with our big bosoms and butts, our black-rimmed glasses low on the bridges of our broad beaky noses, our dark hair corkscrew curly, we resembled a small flock of intellectual geese in fright wigs, and people struggled to tell us apart. These days it’s less difficult.

Lady is the oldest, and now that she’s one year shy of fifty, she’s begun to look it, soft at the jaw, bruised and creped beneath her eyes. She’s the one who wears nothing but black, not in a chic New York way, but in the way of someone who finds making an effort exhausting. Every day: sweatshirt, jeans, sneakers, all black. “I work in a bookstore,” she says, “and then I come home and stay home. Who do I have to dress up for?” She wears no bra, hasn’t since the 1960s, and these days her breasts sag to her belly, making her seem even rounder than she is. “Who cares?” she says. “It’s not like I’m trying to meet someone.” Her hair, which she wears in a long queue held with a leather and stick barrette, is freighted with gray.

Vee is the tallest (though we are all short), and the thinnest (though none of us is thin). Her face is unlined as if she’s never had any cares, which (she says with good reason) is a laugh. She doesn’t like black, prefers cobalts and purples and emeralds, royal colors that make her look alive even as she’s dying. “Isn’t that what fashion is?” she says. “A nonverbal means of lying about the sad, naked truth?” She wears no bra either, but in her case it’s because she has no breasts. She has no hair either. Chemo-induced alopecia, they call it. No hair, no eyebrows, no eyelashes. Her underarms, her legs—they’re little-girl smooth. As is the rest of her. Little-girl smooth.

Delph is still the baby. Even now, two years into her forties, she looks much younger than the other two. She’s the smallest, barely five foot one, and the chubbiest, and she still wears girlish clothes: white peasant blouses with embroidery and drawstrings; long floral skirts that sometimes skim the ground, the hems frayed from sidewalks. As for her hair, it’s always been the longest, the wildest, the curliest, those curls bouffanting into the air, rippling down her back, tendriling around her big hoop earrings, falling into her mouth, spiraling down into her eyes. She says there’s nothing to be done about it; it’s just the way her hair wants to be. “There’s plenty to be done about it,” Vee has said more than once. “Just get me a pair of hedge clippers, and I’ll show you.”

So: black-clad, gray-haired, saggy, baggy Lady. Pale-skinned, bald-headed, flat-chested Vee. And little Delph. Three easily distinguishable women. And yet people still mix us up. The aged super who has known us since we were children. Our neighbors, old and new. We don’t resent it. Even our mother used to get jumbled up and call us by the wrong names. Sometimes we do it ourselves.

“I’m Delph,” Delph will say to Lady, who has just called her Vee for the third time in an evening. Most of the time, though, we let it go.

And sometimes one of us, sleepy or tipsy, catches a glimpse of herself in a mirror, and for a moment even she mistakes herself for one of the others.

Also, sometimes we confuse things by wearing each other’s clothes.

Like many of the Alter women in the generations before ours, we were named for flowers—but Lady is how Lily pronounced her name as a toddler, and it stuck; Vee is as much of Veronica as anyone has ever bothered to utter; and Delph is short for Delphine, which our mother thought was the name of the vivid blue perennial, but actually means “like a dolphin.” We don’t mind the nicknames. You might even say we’ve cultivated them. The flower names our mother picked never thrilled us. The funereal lily. The purple veronica, known for its ability to withstand neglect. Delph’s name that isn’t quite what it was supposed to be. “Neither the gods of flora nor the gods of fauna knew who had jurisdiction over me,” Delph likes to declaim. “No wonder I fell through the cracks.”

The truth is, we all fell through the cracks, and that’s where we’ve stayed. Our father left when Lady was seven, Vee four, Delph swaddled. Our mother … well, that’s another sad story. But life between the cracks isn’t so bad when you’ve got sisters. It can be cozy and warm, when that’s what you want. It can be filled with in-jokes and conversational shorthand and foolishness, if that’s what’s needed. Or it can be silent and still, which we tend to appreciate these days, given that, in addition to everything else, we’ve grown ever more introverted, even a touch agoraphobic.

All of which makes us well suited to the project we embark upon tonight, namely writing this whatever-it-is—this memoir, this family history, this quasi-confessional.

Our subject is the last four generations of Alters, up through and including our own. We plan to record all the sorrows and stumbles as well as all the accomplishments and contributions. We’re sorry to say there’ve been many of the former, far fewer of the latter. This is especially true when it comes to our own generation. We’re the entirety of the fourth generation; we’re the last of the Alter line; we’re “that’s all there is, there ain’t no more”; and we’ve brought the family name no glory.

On the other hand, we’ve brought it no shame either, which is more than certain preceding generations can say. That first generation, for instance, which starred our infamous great-grandfather, Lorenz Otto Alter, World War I hero, World War I criminal. Genius and monster. He was the sinner who doomed us all.

Still, he accomplished things. Good things, bad things, Nobel Prize–winning things. Not so the three of us. We’ve accomplished nothing, contributed even less, and we fear for the poor sap who’ll someday be saddled with our eulogies. What will this hapless orator say? Delph Alter, the youngest sister, never left a filing cabinet less organized than she found it. Vee Alter, the benighted monkey in the middle, spent her entire adult life as a paralegal at a law firm where she drafted wills and settled estates—a deadly occupation. Lady Alter, the eldest, stood behind a cash register, ringing up purchases of paperbacks and magazines, saying little all day besides thank you and do you need a bag for that and romance is the third aisle on your left.

Clearly all three died of excruciating boredom.

Yit’kadal v’yit’kadash. Requiescat in pace. Th-th-that’s all, folks.

We’ve been thinking about our eulogies lately because this is not only our memoir, it’s also our suicide note. It’s true: we’ve set the date at last. Midnight, December 31, 1999. New Year’s Eve.

We’ve always known we’d die by our own hands sooner or later. Sooner has now come a-knocking.

“Six months to a year.” That’s what Vee’s doctor said.

We talked it over at dinner. We slept on it that night. The next morning we made a pact. All for one and one for all. If one of us goes, all of us go. Everybody out of the pool.

We have a joke. Well, not a joke. A riddle:

Q: How do three sisters write a single suicide note?

A: The same way a porcupine makes love: carefully.

Also, tenderly and slowly and by pressing on even when it hurts.

We also have a chart. A week or so after our mother died, Delph, who was then eighteen, drew it up. She made it pretty and tacked it onto the back of her bedroom door, where some girls hang pictures of teen idols. There it remains, our great-grandfather, the curse’s catalyst, near the top, and our mother, the hapless Dahlie, down at the bottom, bearing his weight and the weight of all the others who went before her.

We like the chart. We like the tidiness of the rows and columns. We like the repetitions and subtle variations. We’re fascinated by the emergent narrative.

It’s said that descendants of suicides view life as forever chaotic, but when we look at this chart, we see the opposite of chaos. We see order and routine. We see soothing predictability and reassuring inevitability.

Without the rows and columns, all you’d have is a crazy game of Clue. Great-Grandma Iris in the garden with a gun. Aunt Violet in the bedroom with a plastic bag. Mom in the river with rocks in her socks.

But with the rows and columns, you have our family tree. Every family’s got one. This one is ours.