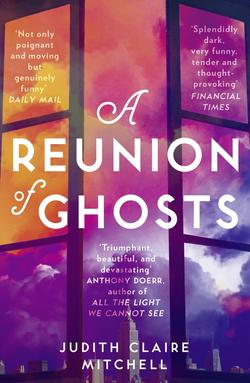

Читать книгу A Reunion of Ghosts - Judith Mitchell Claire - Страница 17

1879–1881

ОглавлениеFrom the essay “A Word about Our Jews” by Heinrich von Treitschke, professor, historian, deputy to the Reichstag, and archconservative:

Year after year, out of the inexhaustible Polish cradle there streams over our eastern border a host of hustling, pants peddling youths, whose children and children’s children will someday command Germany’s stock exchanges and newspapers … What we have to demand of our Israelite fellow citizens is simple: they should become Germans. They should feel themselves, modestly and properly, German.

From the pamphlet “Another Word about Our Jews” by Theodor Mommsen, professor, classical scholar, Nobel laureate, and ultraliberal:

Remaining outside the boundaries of Christendom and at the same time belonging to the German nation is possible, but difficult and risky … He whose conscience does not permit him to renounce his Judaism and accept Christianity will act accordingly, but he should be prepared to bear the consequences … The admission to a large nation has its price. It is the Jews’ duty to do away with their particularities … They must make up their minds and tear down all barriers between themselves and their German compatriots.

From the mind of Lenz Alter, age twelve: Where’s the problem? Everyone’s taking sides, von Treitschke versus Mommsen, but it seems to Lenz the two men are in agreement. Yes, it’s true that von Treitschke hates the Jews, while Mommsen only suspects them, but they both advocate the same solution: hatred and/or suspicion will vanish if the Jews become truly, completely German. What’s there to debate, then? Where’s the disagreement? Where’s the conflict?

And given that both of these men, respected and learned men, German patriots, agree that what the Jew must do to become truly German is simply give up Judaism—well, Lenz doesn’t understand why it hasn’t already been done. En masse, as a celebration, a festival. Has a less onerous task ever been asked of a people? It’s not as if he or his father or his uncles or any of the Jews he knows use their Judaism for anything.

Heinrich and Lenz sit at the polished walnut table in the dining room, draperies drawn, observing their usual prandial silence. The new housekeeper sashays in, seventeen if a day, her soup tureen held low by her hip as if she’s a milkmaid coming in from the cow barn. Heinrich observes the excessively long and somewhat perilous arc of her ladle as it carries the hot broth from tureen to bowl. He’s wondering if he should correct her form when Lenz unexpectedly speaks.

“I have a question of philosophy and conduct,” he says.

“Do you?” says Heinrich.

“Oh, my,” says the housekeeper.

“I’ve been wondering, given the general consensus that two of my three fathers cannot happily coexist, which of those two should I please: Chancellor Bismarck or God?”

“I thought Bismarck was God,” the housekeeper says. Heinrich, who likes his housekeepers quiet and reverent especially vis-à-vis Bismarck, decides he will fire this one later that evening. As it turns out, though, after dinner he’ll become distracted rereading his Mommsen and will forget all about her. Then one thing will lead to another, and within a year he and the housekeeper will be married, and Lenz will have a stepmother a mere five years older than himself, which will require extensive revision to the fantasies he’d been enjoying since she arrived.

“It’s not a matter of either/or,” Heinrich says. “In this house we stick to our own flag. You’re a Prussian Jew who does what I say. And thus do your fathers coexist.”

It’s not until the next evening that Heinrich suddenly puts down his knife and fork and says, as if no time has passed since Lenz brought it up, “I’ll say only this and I’ll say it only once. Convert, and you no longer have this father.” He picks up the utensils again, attacks his dinner, the only violence life allows him.

The man who practices nothing of his faith clings to it nonetheless. It makes no sense to Lenz; it never will. For now, though, he backs down. “I didn’t say I was going to convert,” he mutters. What he wants to say, but can’t, not yet, is that if he converts, yes, he may lose Heinrich. And of course this Yahweh he’s heard so much about but has never really been introduced to—he would also go by the boards. But Lenz wouldn’t be completely orphaned. He’d still have the best of the lot.

Sometimes we picture it carved into the bark of a tree:

Otto von B. + Lenz A. = true luv 4-ever.