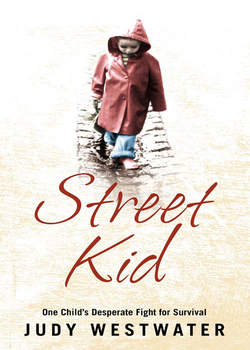

Читать книгу Street Kid: One Child’s Desperate Fight for Survival - Judy Westwater - Страница 10

Chapter Six

ОглавлениеThe next morning, Freda showed me what my duties were. She took a cold and savage pleasure in pointing out every little thing that needed to be done, jabbing her bony finger at a hospital corner on her bed-clothes, or a crevice in the iron range that needed to be cleaned just so. She had her other hand on her hip and spoke to me as if I was an idiot.

So began my new life as a seven-year-old slave in the town of Hulme.

The next morning, as soon as it was light, I got up, dressed and went downstairs. Freda and my father were still in bed and the house was chill in the grey light of early morning.

First, as instructed by Freda, I emptied the ash dust out of the grate in the kitchen fireplace, then cleaned the fire back and put aside the partially burned pieces of wood to use later. Next, I let myself out of the back door, loaded two buckets with coal from a heap in the yard, and chopped the large logs of wood into smaller pieces with an axe.

I struggled to remember what Freda had told me and kept getting it wrong or would forget something. She’d instructed me how to lay the fire and I knew she wanted the coal positioned in a certain pattern, but I couldn’t remember if the smaller pieces should be put on first or the bigger. I felt hot and panicky. If it wasn’t just so, I knew that Freda would hit me.

After laying the fire, I scrubbed the hearth, then cleaned the ashes off the mantelpiece. By now, I was exhausted but I still had to lay the kitchen table for breakfast and fill a kettle with water so I could wash up last night’s pots and pans.

A week later, black and blue from Freda’s beatings, I started at Duke Street School; and then things became even tougher for me, as all my chores had to be done before I left.

Freda had a part-time cleaning job in the flat behind the local newsagents. She wasn’t home when I got back from my first day at school. She’d given me a key to let myself in with which I wore around my neck on a string. I soon realized that she didn’t like to be there when I was doing all the afternoon chores; so if she wasn’t working, she’d be down at Lewis’s or Pauldines, Manchester’s big department stores, shopping with her friend Madge or having tea round at her house.

I let myself into the house and quickly got to work. I started by sweeping the floor, then washed the lino in the front room with a scrubbing brush and a cloth. Next I went upstairs. I was dreading going into Freda and Dad’s room as I felt at any moment that one of them might walk in. I quickly made the bed then hung up any clothes strewn about the room. Lastly, the worst job of all.

I bent down and slid the chamber pot out from under the bed. It was full of urine and, to my disgust, there was excrement there too, the smell of which made me gag. I carried the heavy pot across the room and down the stairs. A couple of times, on the way to the outdoor toilet, urine slopped over the sides so that, after scrubbing and drying the pot, I had to get a cloth and bucket and wash the stairs too.

My next job was scrubbing the kitchen floor. If Freda so much as noticed one little pool of water left between the uneven flags I’d get a beating. Everything had to be perfect. She’d slapped me across the face the previous week when I’d failed to do up the buttons on her blouse before hanging it up. I didn’t even know that was how it was meant to be done, but I knew excuses would be pointless.

Freda also delighted in inspecting every nook and cranny in the range, knowing that it was the hardest job to do well. If she’d been cooking something that had boiled over, like a rice pudding, I had to use wire wool to clean the brown, crispy gunge from the oven and it made my fingers bleed. Once a week, I had to black-lead the range – the previous day it had taken me an hour and a half.

I’d just finished my chores by the time Freda got home. The moment I heard her open the front door and put down her bags, my heart began to pound. I stood hiding behind my bedroom door, hardly daring to breathe and listening with every nerve-end to the sounds she made as she moved around the front room and kitchen inspecting my work.

Then came Freda’s steps on the stairs. I heard her walking round her bedroom checking everything. Then she came back out onto the landing outside my door.

Please go downstairs. Please let everything be perfect!

Freda opened my door. ‘Get out from behind there!’ Her voice was icy. ‘You’ve been lazy again, you idiot girl. Can’t you ever do anything right?’ Freda’s mouth was set in a hard line and her eyes were slits of fury. Snatching the library book I’d been reading, she lunged at me, whacking me across the head with it.

‘I’m confiscating this, and maybe then you’ll learn.’

Somehow, with an unerring instinct, Freda knew that this would be the worst punishment of all. In taking my book, she took away my one source of escape.

I lay on my bed dry eyed. I could almost feel myself pushing down the emotion I felt and locking it away in a cold, secret box in my chest. However beaten or bullied I was, however great the injustice done to me, I could never speak up to defend myself and I’d never learned to cry. I discovered from the moment I was born that tears would never bring comfort or caresses, only harsh words. And now here I was, seven years old and never daring to speak in case I got hit across the mouth for it.

I lay there in the dusk, watching the gas lamp’s greenish glow cast strange shadows on my wall and feeling the cold box in my chest weighing me down, a huge, hard lump that could never be eased by tears.

My father would get up after I’d left for school in the morning, have his breakfast and leave for work. He had a job as a fitter and turner at a company called Three Six Five. He was a vain man, obsessed with maintaining the new veneer of respectability he and Freda had created, and didn’t want to be seen coming home in his overalls like the other blue-collar workers. He hated the idea of our neighbours knowing he was a fitter, so he changed into his normal clothes at work before coming home.

One of the things my father obsessed about was having a perfectly polished doorstep. Freda had shown me how to use the donkey stone she’d got in exchange for rags from the rag-and-bone man. It was made of crushed stone, bleach, and cement and was used by all the housewives in our street to scour and colour their doorsteps. ‘Doing the step’ was another of my daily chores.

First, I’d bring out a bucket of warm water and a cloth and wipe down the doorstep. Then I’d wet the donkey stone, taking off a layer of the chalky stuff with my cloth. The paste was then spread on the step and left to dry. It left a smooth caramelly residue and, with a clean cloth and water, I’d wash around it carefully to make a perfect semicircle. My father always insisted on a half-moon shape. Everyone else in the street had their step coloured in a square, but he wanted to show he was better than them. It was very hard marking out the semicircle, but I knew Dad would beat me if I didn’t do it perfectly.

On my first Saturday in Hulme, I was lying on my bed when I heard the rag-and-bone man outside shouting, ‘Any old rags!’

‘Judy, get down here now!’ Freda’s voice made me jump.

I ran downstairs. Freda shoved an old white shirt of my father’s, and a few other bits of clothing and rags, into my arms and told me to get a donkey stone.

I went outside into the winter sunshine. A group of kids from the neighbouring houses had collected on the street with their armfuls of rags, twittering with excitement.

The rag-and-bone-man had longish, grizzled hair and was unshaven. His trousers were kept up with string, but his big shire horse didn’t look badly fed. He probably wasn’t that hard up as he was paid good money for a ton of rags across town at the paper factory.

One by one, the children gave the man their bags of old clothes and he held up a selection of toys they could choose from. One girl with an especially big bundle of rags was allowed to take a bat with a ball attached by a piece of elastic. I looked longingly at the bazooka, which I’d seen the other children blowing into and which made a really funny buzzy sound. ‘So what do you want, love?’ the rag-and-bone man asked me.

I knew what I had to say.

‘A donkey stone.’

‘Here you are then.’ He handed the chalky cream block to me. I went back indoors, not wanting to stick around watching the other kids playing with their new toys; but I could hear the buzzing from their bazookas and the loud clacks as they flicked their wooden clappers as I walked back over the cobblestones.

Another chore Freda gave me was humping our tin bath, full of dirty laundry, down to the wash house. Doing the washing, when no one in our street had hot water or a tub, was something that took the women most of the day. The wash house was only a short walk from our terrace, and a crowd of women would set out in the early morning, dressed in flowery overalls, hair tidied away in brightly coloured scarves tied in a knot at the top. In front of them, they’d be pushing old prams piled up with the week’s washing.

Freda used to do the laundry at the wash house, but it was my responsibility to get it there in the morning before school. I used to look longingly at the women’s prams as I staggered along the street carrying our huge tin bath. Freda didn’t bother to wonder how I’d be able to make it the three hundred yards to the washhouse; she’d just load up the bath and boot me out the door. I knew I would get into trouble if I dragged the bath, so I had to hold it out in front of me. It was back-breaking work, and every few steps I had to stop and put it down.

When I got to the wash house, I’d hand my shilling over and take the yellow ticket the lady behind the counter held out to me. Inside the building, on the ground floor, there were huge sinks with big copper taps along one wall. I’d put my tin bath down next to one of them, thus bagging it for Freda, who would be along later.

Doing the laundry would take Freda a good part of the day. First she’d use the plunger and scrubbing board to wash our clothes and sheets. After each load, she’d use the mangle to wring as much water as she could from them; then she’d dump them in one of the big steel spinners in the middle of the room. Along the side wall were wooden drying racks in heated compartments. Freda would pull one of them out, hang her clothes on it, and leave them drying there until the next load was ready. Lastly, she did some of the ironing, bringing the rest home for me to do.

Upstairs at the wash house were the public baths, and once a month I was allowed to go there. I’d run along our street with my towel, relishing the thought of a long soak. I paid my money and walked up the stairs to where there were several green-painted cubicles. The lady attendant was small and fat, with a big booming voice, and her curls tucked away in a hairnet.

Once in my cubicle, it was quite a task for me to get into the high bath; but, once in, I’d call to the lady attendant to put in the water.

Then came the fun bit: ‘More hot, please! … That’s enough! … More cold!’

When the bath was nice and full, and steaming hot, I’d lie back in the water. The tub was so big that I could swim in it. Once or twice I got into trouble for splashing the floor as I used to sit on the end of the bath and then slide down it in a whoosh of water.

I loved bathtime so much that I’d have liked to have stayed there all day, but our time was sharply monitored.

‘Time’s up, number three!’ bawled the small lady with the big voice. And then the fun was over for another month.