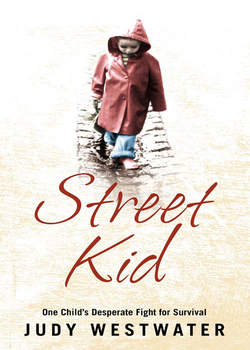

Читать книгу Street Kid: One Child’s Desperate Fight for Survival - Judy Westwater - Страница 6

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеFreda never gave me anything to eat or drink in the mornings. Whenever I got thirsty, I’d scoop water from the toilet; but there was nothing I could do to calm the gnawing hunger I felt every day.

It wasn’t long before I made my escape from the yard. One day I stood on tiptoe to reach the bolt on the back gate. I pulled on it with all my strength and when it slid back it cut my hand. But it didn’t matter to me that it was bleeding because I’d got out. The only worry I had was that now I’d opened the door, I couldn’t close it from the other side. But a second later I managed to slip the toe of my sandal underneath and closed it. I felt very proud of myself.

On the other side of the gate I was faced with a high stone wall with a path running along in front of it leading to a small green square with rows of houses backing onto it. As I stood there on the grass, a boy came up to me. He must have been about twelve.

‘You alright? Are you lost or something?’ I didn’t answer, didn’t run away either. I just stood there. Then he went away.

From time to time I noticed women coming out of their back doors carrying bags of rubbish over to the low, open-topped bins at each corner of the square. My tummy hurt from hunger and so, as soon as the women were gone, I went over to one of the bins, stood on a brick, and leaned in to hunt for scraps.

The smell was almost overpowering, but I delved down into the damp and greasy rubbish, rummaging through it looking for something edible. I found a promising looking newspaper parcel and unfolded it. Inside there was a handful of potato peelings and some chicken bones. I picked up a bone and sucked on it, tearing off a few tiny strands of meat with my teeth. It tasted good, but didn’t satisfy my hunger one bit, so I started on the peelings. They didn’t taste nice at all. After eating as many of them as I could stomach, I leaned further over the bin and dug down deeper, looking for other newspaper parcels. I spotted one, and pulled it loose. It contained an old crust of bread and some bacon rind, which I eagerly devoured.

That first time I ventured out of the yard, I didn’t go any further than the square behind our houses, but it wasn’t long before I was exploring the rest of the neighbourhood. I wandered down the gutters and cobbled alleyways that ran between the rows and rows of back-to-back brick houses. None of them had front gardens or yards and, without a flowerbed or patch of grass to bring colour to the streets, Patricroft was a monotonous place of grey stone and sooty brick. The only things that brought colour to the place were the barges which shipped their cargo along the old canal. I’d stand on the iron bridge and watch them for hours as they made their slow progress through the tar-coloured water, littered with bottles and other bits of rubbish. If anyone came towards me I’d run away and hide.

One day, about three months after we’d moved to Patricroft, and soon after I’d first escaped from the yard, I walked past a gate, through which I could see some grass. Thinking it must be the entrance to a park, I pushed open the gate and went in. I found myself in a large garden, with beds of beautiful flowers planted in patterns. I’d never seen anything so wonderful in my life, and wandered through the garden in the sunshine, hardly aware of time.

After a while, I thought I’d better go home – it must have been mid-afternoon at least, and I was always careful to get back to the yard in good time. But when I looked for the gate I couldn’t find it. I began to wander further and then started to panic. I skirted the big, grey stone wall of the building in the centre of the garden, thinking that if I went round it I might find my way back to where I started. Then, as I came round the corner, I was met by a curious sight.

Groups of children in grey uniforms were playing on the grass in little groups. Moving about amongst them was the strangest looking person I’d ever seen. She was wearing a long black dress that flapped as she floated along the grass, and her hair was completely covered with black cloth too. She was gliding along as if on motorized wheels. It was my first sight of a nun.

I watched for about ten minutes, and then a loud clanging noise almost had me jumping out of my skin. One minute it had been quiet and peaceful, the next a huge bell was ringing right above my head. I crouched by the big stone steps, frozen in terror and certain that it was telling everybody where I was. I thought I might have stood on something and set it off.

My fear grew even worse when the groups of children starting coming towards me. They came over to the steps and lined up in pairs. I was crouching down between a shrub and the side of the steps, watching the children as they went up, hand in hand. About ten pairs went by without seeing me, but then I must have made some little movement. My eyes met those of a little girl. It was clear she’d spotted me: she began to tug on the nun’s sleeve and said something to her while looking back at me. Then the nun turned and glided over, her big black dress flapping as she came.

‘What are you doing here? What is your name?’ I knew my name but I couldn’t say it. I couldn’t speak to her.

‘Come with me.’ I couldn’t move. When someone said ‘Come with me’ it always meant only one thing. I was certain the nun was going to beat me for being in her garden.

She took my hand and beckoned to the little girl who’d seen me. ‘Josephine, I’d like you to take her to the kitchen.’ Her tone of voice wasn’t particularly warm, but at least I wasn’t getting beaten yet.

The girl took my hand and we both went up the steps together. It felt like I was entering a huge mouth as we went through the great doorway. I’m going to get swallowed, I thought to myself. We walked through the hall, which smelled of polish, to an enormous kitchen with a long scrubbed wood table in the middle. The only things that brought brightness and colour to the stark room were the copper pans hanging on the walls. Everything else had a sober black and white formality, and even the older girls who were preparing food on tables around the sides of the room in their white dresses looked austere. I was told to sit down and one of the girls brought me a slice of bread and jam, which I devoured hastily, despite my apprehension.

The woman in black came in and began asking me questions again.

‘Where do you live? Just tell me your name.’

I looked at her, still unable to speak.

She was huffing and puffing, quite irritated now. She left the room but returned a few minutes later with a group of girls and boys.

‘Do any of you know this girl? Have you seen her before?’ No one answered.

The nun appeared even more exasperated and turned back to me.

‘Come on, we’d better go and see if we can find where you live.’

She took my hand and we went out of the kitchen, back through the hall and out into the sunshine again. We went through a different gate to the one I’d come in by. It was bigger and led onto the main road, with the canal opposite. I told the nun that I knew where we were and made to go; but, to my horror, she kept hold of my hand and began to march me up the street towards the door of the shop.

But I can’t go in the front! Don’t take me in that way! The panic was rising in a swift tide and washing over me. Don’t take me in that way! I’m supposed to be in the yard!

The bell tinkled as the nun pushed open the shop door. Freda was looking over from the counter at the back.

‘Is this your child?’

Freda said that I was and thanked her very sweetly for bringing me back. Then, as soon as the nun had left, she took me into the back room and closed the dividing door.

‘Don’t you ever dare go out again.’ she screamed. ‘Never, ever come in the front, and never ever leave the yard. Do you hear what I’m saying? I’m going to tell your father when he gets back.’

Then she began to lay into me, punching and kicking. She boxed my ears, which she’d done before, only this time the pain was more excruciating. It felt like sharp daggers in my head. I heard a pop and a horrible kind of rushing sound. Freda stopped hitting me and stood, breathing quickly, hands on hips, glaring down at me.

‘Get up to your room,’ she hissed. ‘I don’t know why I bother to look after you. You disgust me.’

It was only after I’d got upstairs and crawled under the blanket that I realized I was completely deaf in my right ear.

The next morning Freda recovered her energy and as soon as I’d crept downstairs, heading for my hiding place under the table, she grabbed me and began shouting at me again, calling me a little piece of vermin. She hadn’t told my father: I knew she wouldn’t, because she would only have got in trouble herself. If he was crossed, he could get extremely vicious; a cold brutality came over him which even Freda, who usually gave as good as she got, was scared of. My dad was always paranoid that someone would pry into his business. He’d come up against the welfare board before, and he didn’t want anyone poking their nose into his life now.

Freda grabbed me by the hair and threw me at the back door. She then opened the door and gave me a kick, which sent me tumbling down the steps. I gashed one of my knees against the step, and when I picked myself up at the bottom of the steps I couldn’t put any weight on it at first, it was so painful. Then I looked down and saw blood trickling down my leg. I gave a little whimper, but not because of the pain. My dress had got blood on it from the gash and I was suddenly sick to my stomach with terror, knowing that Freda would punish me for getting it dirty. I’d already been beaten by her for losing my bobble hat, and I knew that she’d seize any excuse to beat me.

I hobbled gingerly across the yard to the outside toilet, where I took a square of newspaper from the bundle that hung from a piece of string. Dipping it in the toilet pan, I tried desperately to scrub the blood off my dress with the sodden paper until my arm was shaking, but the blood wouldn’t come off.

When Freda let me in later, she looked at my tear-stained face and I knew it made her want to beat the hell out of me. When she saw the state of my dress, stained with blood and spotted with little bits of newspaper, she snatched up the cheese triangle that was sitting on the table and said, ‘Right, for that you won’t be having any tea, my girl.’ As I hadn’t been out of the yard that day, I hadn’t managed to scavenge anything from the bins, so I was sent to bed with hunger pains gnawing at my insides.

It was only two days later that I once again fell foul of Freda in a big way. It was a sunny day and I was playing in the yard, walking carefully on tiptoe from bar to bar of the iron grate that covered the cellar window. All of a sudden, I slipped and fell, saving myself with my arm. However, my foot had fallen between two of the bars and my leg was dangling in the gap between grate and window. When I tried to pull it out, my knee was in the way; so I tugged and tugged at it, trying to yank it free, becoming more and more panicked that Freda would find me wedged there later when she opened the door. But I couldn’t see how I was going to free myself. I was totally trapped and unable to work out why my knee wasn’t able to slip back through the way it had gone in. After several minutes of frenzied pulling, my knee got past the bars, but then I found out that my foot in its sandal couldn’t get through. I struggled with it until finally my foot came free, but by then my shoe had come off and fallen through the bars.

My leg was cut and bruised and very sore, but I was more worried about my sandal, which was lying below the iron grate, about three feet down. I knew I’d get into terrible trouble if I didn’t get it back, so I lay down on the grate and stretched my right arm through the bars. My fingertips didn’t even nearly touch it, but I wasn’t about to give up. Come on, you can reach it. Come on! I couldn’t bear to think about what Freda would do if she found I’d lost a shoe. So, again and again, I ground the side of my face down onto the bars in a frenzied attempt to reach my sandal.

When at last I stood up and looked down at my bare foot, I realized that my dress had got dirty from lying on the ground. There was nothing more I could do, so I went over and sat on the steps, where I remained for the next two hours, stiff with fear and awaiting my fate.

When I heard Freda unlock the door, I tried to creep in without catching her eye, but she saw the state of me at once.

‘What the hell have you been doing, and where’s your shoe?’

I just stared back at her, too terrified to say anything.

She grabbed my arm, pinching it viciously. ‘You answer me, damn it! Where’s your bloody shoe?’

She yanked my arm and pulled me outside and down the steps. I pointed at the iron grate.

‘You little swine. Didn’t I tell you not to move? What the hell were you doing throwing your shoe down there?’ She poked my forehead with a finger, jabbing it at me so hard my neck snapped back.

Then she went back inside and a minute later I heard her trying to open the cellar window. It was stuck. A moment later, she returned.

‘Right, Missie, you lie down and get it!’

I tried to tell her it was no use my trying, but she wasn’t listening.

She pushed me down and forced my arm between the bars, though she could see perfectly well that it wasn’t nearly long enough to reach the sandal. She put her foot down on my shoulder and pushed. The bars were crushing my chest, making it impossible to breathe.

After a while she dragged me back inside and looked around the room for something long enough to reach the shoe. Finally she stood on a chair, took down the curtain rod, and unhooked the curtain from it. ‘Don’t you dare move!’ she said, taking the rod outside.

A couple of minutes later she came back with the shoe in her left hand. In her right, she held the rod. She whacked me hard across the face with the shoe, making me reel back with the shock of it.

‘Get upstairs, damn you,’ she snarled. Her eyes were dark slits in her white face.

But as I turned to scramble up the stairs and out of her way, she went for me with the rod, savagely beating the back of my legs. I crumpled to the floor and continued up the stairs on my hands and knees. I felt her black snake-eyes on my back as I turned the corner to my room.