Читать книгу Travel Scholarships - Jules Verne - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

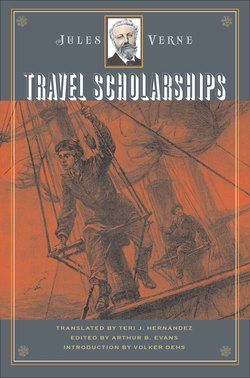

This first English edition of Jules Verne’s Travel Scholarships constitutes an important milestone both in Verne studies and in Wesleyan University Press’s “Early Classics of Science Fiction” book series. It is the last Verne novel for which there has existed no English translation; Anglophone aficionados of Verne will finally to be able to read this long-neglected work. When the Early Classics of Science Fiction series was established in 2000, it had three main goals: to provide high-quality critical editions of important early works of science fiction (SF) from around the world, to publish critical works that focus primarily on early SF, and to make available new and updated English translations of the works of Jules Verne. At that time, there were still four novels of Verne’s Extraordinary Voyages (Voyages extraordinaires) that had never been translated into English. In early 2001, the ECSF series debuted with the first of them, Verne’s 1905 Invasion of the Sea (Invasion de la mer); the following year, we published the second, his 1898 The Mighty Orinoco (Le Superbe Orénoque); five years later, the third appeared, his 1902 The Kip Brothers (Les Frères Kip); and now we present the final one, his 1903 Travel Scholarships (Bourses de voyage).

It might seem perplexing that these Verne novels remained untranslated for so long, especially since Verne is ranked (with Shakespeare) among the top three most translated authors of all time, according to UNESCO’S Index Translationum. The exact historical reasons are difficult to discern in retrospect, but they no doubt involved issues of profit, ideology, and genre.

Toward the end of Verne’s illustrious writing career (1863–1905), he had many rivals who, emulating his success, flooded the marketplace with similar scientific-adventure novels. Not least among these popular new authors was the young British writer H. G. Wells, whose The Time Machine (1895), The War of the Worlds (1898), and The First Men in the Moon (1901), among other speculative works, were suddenly all the rage. Since the 1890s, Verne’s own popularity had been waning, and sales of his Extraordinary Voyages were beginning to lag. It is therefore not surprising that Anglo-American publishing houses saw little profit potential in bringing these final Verne novels to market.

As pointed out by Brian Taves in The Jules Verne Encyclopedia (1996), another reason why many of Verne’s later works were not immediately translated into English had to do with their ideological content:

The tenor of his new works were less agreeable to English-speaking audiences, or at least their publishers, who were not prepared to faithfully present Verne’s views. The censorship grew beyond simply changing or removing controversial passages until eventually entire books were suppressed by simply not translating them into English. (16)

It is true that most of Verne’s later works differ greatly from his earlier, best-selling novels that were published under the guiding (and sometimes autocratic) hand of his publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel. After Hetzel’s death in 1886, one can observe a gradual but palpable shift in Verne’s worldview. He more frequently champions issues of environmentalism, anticapitalism, and social responsibility, often questioning the benefits that science and technology can bring to an imperfect world.

The third most likely reason why these late novels by Jules Verne were not published in English had to do with the literary genre that Verne (rightly or wrongly) was seen to represent among the Anglo-American reading public. Since the early years of the twentieth century, Verne was widely celebrated as the “Father of Science Fiction.” His name became synonymous with prescient technological predictions; he was known to have inspired many future scientists and explorers; and his works were recognized around the world as prototypes for what would later be called the “sci-fi” genre. In contrast, many of his late novels such as Travel Scholarships simply did not fit the mold. Their plots, lacking any futuristic technology or scientific extrapolation of any sort, seemed so un-Vernian. Marketing such atypical texts to the Anglo-American public was probably viewed as a risky proposition, so publishers simply chose not to translate them at all.

It is important to note that the availability of good English translations and serious English-language critical studies of Jules Verne and his Extraordinary Voyages has improved dramatically since the 1960s.1 During the centenary of Verne’s death celebrated in 2005, for example, more than fifty new titles appeared. Much credit should be given to Oxford University Press, the University of Nebraska Press, and especially Wesleyan University Press for their pioneering work in providing accurate modern translations of Verne’s texts in affordable, scholarly editions. Coupled with the ongoing efforts of organizations such as the North American Jules Verne Society and its new Palik Series,2 these new editions are helping to restore Verne’s reputation in the Anglophone world and are largely responsible for a recent and remarkably vibrant “Verne renaissance” in contemporary literary studies.

Arthur B. Evans

DePauw University