Читать книгу Travel Scholarships - Jules Verne - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

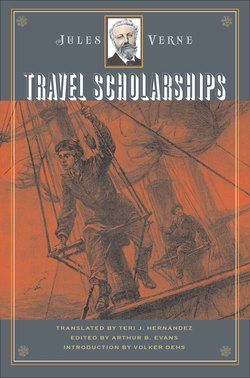

Who among us has read Travel Scholarships, one of the last novels by Jules Verne to be published in his lifetime and the last to be translated into English? Among French readers, and even among experts who study Verne, there are very few who could answer that question affirmatively. It is true that Verne’s oeuvre is vast and includes more than sixty titles—and that is counting only his novels and leaving aside all the short stories, popular science works, stage plays, poetry, and other products of his prolific pen. It is likely that the only people for whom Travel Scholarships would constitute an essential title of unquestionable value are book collectors seeking to complete their sets of handsome octavo Hetzel editions, since this novel is one of the rarest in that published format. Nonetheless, Jules Verne did not write for collectors of expensive editions, but for his readers. His Extraordinary Voyages, epic novels portraying the vast sweep of the universe, have never ceased to transport their readers to the discovery of “known and unknown worlds” (the original subtitle of this series).1 So it seems especially appropriate to embark on our own voyage of discovery within Verne’s oeuvre and explore this unknown opus in his great cycle of novels.

PORTRAIT OF THE AUTHOR IN 1899

While writing Travel Scholarships in 1899, Jules Verne (1828–1905) celebrated his seventy-second birthday. France was preparing to welcome a host of international visitors to Paris for the Exposition Universelle of 1900, a world’s fair that everyone expected would offer a synthesis of the industrial and cultural achievements of the past and present while giving a foretaste of what the future would bring. One might imagine that such an event would be of great interest to the author who earned much fame as the “father of science fiction.”2 But Verne did not even go to the Exposition himself, though his son Michel (1861–1925) was employed there as a member of one of the many preparatory committees. Further, Jules Verne’s name was not even mentioned in the section of the Exposition dedicated to the future or in the opulent Palace of Electricity. His name appeared only in a retrospective exhibit devoted to the history of the French capital, published in a gazette about the history of Paris across the centuries and featuring two brief excerpts from his Geography of France and Its Colonies (Géographie de la France et de ses colonies), which dated from many years before: 1868.3

As the date of the Exposition neared, the Dreyfus Affair increasingly tore France asunder. To calm the protests coming in from abroad and to assure the international success of the big event, the Jewish officer—innocent, but accused of treason and condemned to hard labor—was pardoned just before the opening of the Exposition. But it was not until 1906 that Dreyfus would be fully acquitted and cleared of all charges. The widespread social dissension created by this scandal triggered anti-Semitic excesses among some of Verne’s countrymen and inspired the foundation of the Human Rights League (Ligue des droits de l’homme). The Dreyfus Affair not only divided public opinion for more than a decade, it also tested the solidarity of many French families, including Verne’s own. The new century was beginning under very inharmonious auspices.

More or less everywhere in the so-called civilized world, the approach of the year 1900 had induced an acute anxiety about the future. Political conflicts, fueled by imperialist expansionism and excesses of nationalism, threatened the stability of the international scene. Dubious prophets earnestly proclaimed the impending end of the world by any number of causes: volcanic eruption, flood, earthquake, or collision with a meteor. Great catastrophes were in fashion, and the public was on edge. Nervosité (a highly nervous state) was the word of the day. Verne poked fun at this morbid fascination in his novel The Meteor Hunt (1908, La Chasse au météore), which would not be published until after his death. It mocked such end-of-the-world obsessions by substituting a satire of human greed (which seemed much more scary to Verne) for a cosmic apocalyptic event. In the end, Verne turned out to be right and the false prophets wrong. The real catastrophe would not be caused by a brutal Mother Nature in response to some number from the Gregorian calendar, but rather by humans themselves: it would begin in 1914 with the outbreak of the First World War, when Jules Verne was no longer of this world. By a curious coincidence, the publishing firm of Hetzel, lifelong publisher of Verne’s novels, closed its doors just one month before the declaration of war that abruptly ended the era known euphemistically as la Belle Époque.

In 1899, Verne’s literary career had already spanned thirty-six years. Every year since 1863, with a punctuality that no political or familial calamity had ever interrupted, Verne published two or three volumes in his Extraordinary Voyages series. Travel Scholarships was number 52 on its publication in 1903. What a career! A reader who might have read Five Weeks in a Balloon (1863, Cinq semaines en ballon) at age twenty and who obtained each subsequent book by his favorite author would be sixty when reading Travel Scholarships. This hypothetical reader would be seventy-six when the last official Extraordinary Voyage finally appeared in 1919, revised (or rather, entirely rewritten) by Verne’s son Michel.4

It is necessary to take into account the vast temporal scope of Verne’s career to understand and accept the fact that, in 1899, he was no longer at his peak. Other authors—French, English, American, German, and Italian—had appropriated the concept of his “scientific novel” and were developing its speculative possibilities much more radically than Verne had ever dared to do, in such works as Albert Robida’s The Twentieth Century (1883, Le Vingtième Siècle) or H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds (1898). Despite nearly four decades of tireless production, Verne’s greatest successes had been in the first fifteen years of his work as a novelist. The books that continue to fascinate readers even today nearly all date from this period: Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864, Voyage au centre de la Terre), the lunar novels From the Earth to the Moon (1865, De la Terre à la lune) and Around the Moon (1870, Autour de la lune), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas (1869/70, Vingt mille lieues sous les mers), The Mysterious Island (1874/75, L’Île mystérieuse), Michael Strogoff (1876, Michel Strogoff), and several others. Since those early years, Verne had worked conscientiously and faithfully to depict in his fiction every corner of the globe and to sketch out a portrait of the Earth, similar to how his compatriot writers Honoré de Balzac in The Human Comedy (La Comédie humaine) and Emile Zola in the Rougon-Macquart had sought to create a composite portrait of the societies of their time.

Certain regions, like North and South America, are notable for being featured multiple times in Verne’s oeuvre. Consider, for example, The Last Will of an Eccentric (Le Testament d’un excentrique), also published in 1899, which used the format of the “Game of the Goose” to introduce readers to the various states of the United States, substituting the main characters for the game’s playing pieces.5 On a literary level, this novel probably represents Verne’s boldest concept; but the author soon discovered that fleshing out its complicated plan was proving very difficult to accomplish (as he admitted to his publisher), and it shows in the final result, interesting though it may be.

It had already been nearly thirty years since Verne had moved from Paris to the provincial town of Amiens, located an hour and a half by express train outside the capital. In 1897, he went to Paris one final time to face a defamation suit brought against him by an inventor, which Verne won. Thereafter, Jules Verne—the great lover of travel—became sedentary. His last trip was to Rouen in September of 1900 for the marriage of his granddaughter Jane de La Rue de Francy to the lieutenant Émile Villalard (he served as a witness for the bride).6

The numerous journalists—mostly English-speaking—who made the trip to Amiens to interview Verne were (like the general public) not especially interested in his recent or current novels. They wanted to meet the “inventor of the submarine,” the father of Captain Nemo and Phileas Fogg, whose eighty-day tour of the globe had become a fashionable record to beat for a dozen years or so. The aging novelist would receive them all obligingly, and he would always recount the same stories to each one, since that was what seemed to interest them.7

Jules Verne was well aware of his failing strength; his health had been quite precarious for about ten years. The wound in his foot that he had received in the attempt made on his life by his nephew Gaston in 1886 had never fully healed. After an unsuccessful operation two decades earlier, Verne was forced to limp. Already half-deaf (he congratulated himself for no longer having to listen to all the stupid things being said around him),8 his vision was declining as well. Because he was afraid to have his cataracts operated on, that particular surgery would never take place. In addition to painful rheumatisms and a perpetual “writer’s cramp,” Verne also suffered from poor digestion and other ailments, all of which he wrote about extensively in his correspondence. Fearful of falling, he rarely left his home. Although doctors had diagnosed his wife Honorine with diabetes, they were unable to recognize this same malady in Verne who, to the end of his days, would be the victim of treatments that were unsuited to his needs and useless for alleviating his physical pain. “That does not prevent me from working, and a lot,” he wrote to his publisher, Louis-Jules Hetzel,9 on March 14, 1899. “What would I do without my work? What would I become?”10

Writing, as he never ceased to affirm, was his elixir of long life. At the same time, it was a very basic necessity, since the bankruptcies of his son Michel and the financial problems of his son-in-law Georges Lefebvre had cost him a good part of his fortune. Verne remained bitter about this for the rest of his life and, as early as 1890, he had definitively decided in his will that Michel would inherit his library and manuscripts, but no money. On top of everything else, Verne had to cover the tuition fees of his three grandsons, who were being educated in an expensive boarding school chosen by their father. Verne regularly lamented in his letters that Michel simply did not understand the value of money. The difficult living that Verne had eked out as a student, playwright, and stockbroker in Paris between 1848 and 1863 had left its mark on him, and he had a very real fear of falling back into poverty. He became extremely frugal, going so far as reusing the blank space on letters he received. This also explains why the Verne household decided in 1900 to leave the big house with the tower11 and move just 500 meters away, back to the house they had inhabited from 1874–1882, which was smaller and less costly to heat.

In 1898, Verne resigned from the prestigious Geography Society of Paris, whose newsletters had constituted one of the most important and reliable sources for his novels. The following year, he decided to no longer attend—or at least to do so much less frequently—the Amiens theater, whose performances he had enjoyed three or four times a week, not just as an enthusiast of the dramatic arts, but also as a director of the city’s cultural affairs. Verne was proud to have been a city councilman in his adopted town since 1888, and it was above all in this capacity that his fellow citizens knew their “monsieur Jules.” Most were more or less indifferent to his literary standing. The latter counted more for the notable conservatives of Amiens, whereas politicians on the left regarded Verne with a distrustful eye. Despite his involvement in the city’s cultural affairs, by 1899 Verne stood out most often by his absence at official meetings. His appearances became rare. The same was true for his attendance at street exhibitions or his participation in the organization of the charity office (of which his wife Honorine was vice president) or the town’s supplementary budget for that year.12

Nonetheless, far from inactive even when ill, Jules Verne took advantage of the opportunity to speed up the process of drafting his novels. Thus, on January 6, 1899, he started The Tales of Jean-Marie Cabidoulin (1901, Les Histoires de Jean-Marie Cabidoulin), the story of a whaling expedition in the Pacific and the Arctic that begins rather uneventfully but then ends entirely in the fantastic—and also in a fog, as would Travel Scholarships. After a month-long break, he began Travel Scholarships on May 1, which was written in two drafts in just four months (and that for a novel of two volumes!). Travel Scholarships was then followed in September of 1899 by The Golden Volcano (posthumous, 1987, Le Volcan d’or) whose two volumes kept Verne busy for an entire year. At the same time, the author corrected the proofs of his novel then being published, The Last Will of an Eccentric, and revised the text of the next one in 1900, Second Homeland (Seconde patrie), on which he had begun working in 1896–97.

This would already seem to be an active schedule, but that was not all. The passing of his one-time collaborator Adolphe d’Ennery, who died at the age of eighty-seven on January 25, 1899, reinvigorated Verne’s playwriting ambitions, one of the great passions in his life. Verne’s two-and-a-half-decades-old collaboration with d’Ennery had already produced elaborate theater adaptations of Around the World in Eighty Days (1874, Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours) and of Michel Strogoff (1880), both of which had been huge successes (and which, in France, would continue to be performed until 1941, filling the coffers of the novelist and his heirs). Two other plays, however, had seen only fleeting success. Between 1888 and 1890, Verne and d’Ennery had attempted to write another grand extravaganza, this time an adaptation of The Tribulations of a Chinese Man in China (1879, Les Tribulations d’un Chinois en Chine), one of the novelist’s more humorous masterpieces. D’Ennery, however, who had grown difficult in his old age, found the results unsatisfying. The pair ran afoul of each other and were unable to settle their differences and finish the play. Of the two manuscripts written by the novelist, the more recent remained unfinished in the desk of the deceased, who had done no further work on it. Far from Paris and restrained by illness, Jules Verne gave his son Michel—who became for this occasion his literary agent—the responsibility of recovering the manuscript and contacting the director of the Châtelet Theater, the biggest theater in Paris. The director seemed interested and arranged for a new collaboration to finish the play. This work occupied Verne throughout all of 1899, alongside the aforementioned novels. However, the effort was ultimately in vain, and the play would never be performed. The whereabouts of these manuscripts is still unknown today.

The seaside resort of Les Petites Dalles, circa 1899.

BIOGRAPHY OF THE NOVEL

Such were the circumstances in which Verne wrote Travel Scholarships. In his working documents, Verne himself carefully noted the dates of writing: “1st V[olume]. 1 May 99 (the 2 vol. drafts finished 18 June) manuscripts of the 2 13 August, finished 31 August.”13 It is worth noting that Verne would finish work on this novel during his last vacation, which he spent with Honorine and Michel’s family at the Petites Dalles beach resort on the Opal Coast from August 28 to September 3, 1899. Two rare photographs from this trip have survived, one showing the novelist, his family, and several friends seated on the beach with an imposing cliff behind as a backdrop.

Verne’s work ledgers and manuscripts provide evidence of his precise and regular work habits: how he always wrote a first version of his novels in pencil and then revised it directly in ink. The manuscript of Travel Scholarships14 reveals four successive stages of writing. First, after dividing the pages vertically into two equal parts, the author began by filling one section with select words or phrases in pencil, made up of key words, more or less complete sentences, or fragments of dialogue (stage 1). Next, or more likely in successive steps, he developed a first version of the text, still in pencil (stage 2, finished June 18). As the second rewriting in ink (stage 3, finished August 13) took only one half of the page, we can still read one of the two earlier versions on the opposing half, although it is rather difficult to decipher. The novel, once written, then underwent a careful revision wherein certain parts were deleted or elaborated (stage 4, finished August 31).

Jules Verne and family vacationing at Les Petites Dalles.

Reading the manuscripts for Travel Scholarships yields no sensational secrets. A search for “censored” passages or episodes, suppressed at the request of his publisher Hetzel as in some earlier novels, would be in vain. Rather, the document clearly shows the author’s desire to condense his text to its most essential elements, to do away with redundancies, to render the narration more elegant, to choose the most fitting expression, and to specify details (dates, distances, measures, etc.), as was his custom. This work also continued throughout the painstaking correction of proofs—which have not survived—between the customary publication of the three successive editions, to which I shall return.15

There are, however, three notable exceptions to this observation about the unremarkable nature of the manuscripts. One sequence in chapters 10 and 11 of the first part was deleted (probably because of its implausibility or cruelty) after appearing in the pre-original edition; the plays on words from the Latin phrase Rosam angelum letorum, a recurring joke in the second part of the novel, were only added in the proofs of 1903; and the denouement was also completely rewritten and expanded in the proofs. These deleted passages and the original version of the ending are reproduced in the Notes to the present edition.

In addition to these modifications, the manuscripts reveal several changes in the names of the protagonists: Kathleen Seymour, whose first name Verne definitively wrote as “Kethlen,” was named “Kathlen” in the manuscript. The names Will Corty and John Carpenter were used interchangeably at first, and that of the cook Wagah varied throughout the text between “Walah” and “Walha.” It was only when correcting the proofs that Verne adopted the final spelling. But these are variations of only secondary importance.

After having reviewed the first part of his novel, Verne presented it to his editor on September 28, 1902 (the eve of the death of his colleague Émile Zola):

I plan, unless otherwise directed, to send you the 1st volume of the new manuscript, Travel Scholarships, tomorrow. Its setting, as I mentioned to you, is the Lesser Antilles. We ought to take advantage of the fact that public attention is currently so keenly focused on that corner of our world. I will simply have to add a note to the chapter devoted to Martinique. Another reason influencing my selection of this novel is the current issue of whether Denmark will cede its islands in the Antilles to the United States. I have need for Danish Antilles, as my heroes are French, English, Dutch, Swedish, and Danish.

I believe that this book will interest our young readers at the same time as it will inform them.

As for the illustrations, it will be easy for you to obtain all you might need from the photographs of the Lesser Antilles. As for myself, should I have any documents, I will be sure to send them to you.16

This letter is the only document of any importance in the correspondence between author and publisher about Travel Scholarships. The concern about current events that the author expressed to Hetzel and that informed the decision to choose this novel for publication among other finished manuscripts that had accumulated in his desk was driven by the eruption of Mount Pelé on the island of Martinique on May 8, 1902, which took 30,000 lives. In response to this catastrophe, Hetzel had already devoted a large part of issue number 179 of his Magasin d’Education et de Récréation (December 1, 1902) to Martinique, including a piece by the illustrator Léon Benett, among others.

Léon Benett (1839–1916) was by profession a civil servant and had traveled extensively in that capacity between 1861 and 1874, visiting Algeria, Cochinchina, Martinique and New Caledonia, among other locations. The sketches he made during these trips prepared him to illustrate, beginning in 1873, a large number of Verne’s novels. He especially excelled at drawing theatrically arranged landscapes. This was certainly the case for Travel Scholarships.17 The photographs that Verne mentioned in his letter were indeed added to the text,18 and these, in addition to twelve large colorized plates, demonstrate an effort on behalf of the publisher to increase the attractiveness of his author’s books after 1899. These two approaches modernized Verne’s works while also accentuating their documentary and educational aspects.

The pre-original edition of the novel was published serially in Hetzel’s Magasin d’Education et de Récréation in two issues a month from January 1 to December 15, 1903. The edition called “in-18” (in two small-format volumes with a limited number of illustrations) came out on June 2919 and on November 9, 1903, in a print run of four editions (at 1,000 copies each). A fifth and final edition (500 copies) came out in 1904 for the first volume and not until 1913–14 for the second. Finally, the cloth-or leather-bound and illustrated edition called “grand in-octavo,” highly prized by collectors today, was published on November 19, 1903, in a single run of 9,600 copies of which 403 copies remained in stock when Hetzel sold his publishing house at Libraire Hachette at the end of June 1914. Some copies from this reserve remained for sale until 1924. These numbers show that Travel Scholarships was not really a commercial success, at least in comparison to the other Extraordinary Voyages that had come before it. Only the posthumous novels published between 1906 and 1919 shared such disappointing sales numbers. The following year, in 1904, translations of Travel Scholarships were published in Germany and Italy. At present, this little-known Verne title has been translated into at least fourteen languages.20 Critical reception has mirrored the general public disinterest, as very few critical studies of the novel have appeared to date. With good reason or not? The reader must decide. The following is what is important to know about the novel.

THE “EXTRAORDINARY” IN THE ANTILLES?

We have seen that the 1902 Martinique volcanic eruption was central to Verne’s decision to prepare Travel Scholarships for publication in 1903. For several centuries, the Lesser Antilles had been a plaything of the great European powers, and Verne recounts this unsettled history with ironic detachment. The colonial period was marked by often-bloody conflicts, first between Europeans and the indigenous peoples (who were nearly exterminated), then among the Europeans themselves, and finally between European settlers and the former slaves imported from Africa who had been increasingly enfranchised from 1804 onward. Does this region, which was so well suited to European colonial appetites, lend itself equally well as a setting for an adventure novel? It would certainly be an exaggeration to call Travel Scholarships an Extraordinary Voyage, at least as most readers understand the epithet “extraordinary.” But few of Verne’s novels published after 1880 were, in the real sense of the word. The author was more interested in completing his “criss-crossing of the globe” (an expression used by Daniel Compère),21 a goal that Verne had made his life’s work, even though he knew the task would never be truly finished. Since the regions described in this novel were already well known, the idea of a journey of exploration had to give way to a simple tourist trip. The latter naturally elicited far less interest than the former, unless it were complemented by satirical or humorous elements, as in The Thompson Travel Agency (1907, L’Agence Thompson and Co), a late novel published by Michel Verne under his father’s name.

The Antilles provide the backdrop for the novel’s action, and the islands are discussed geographically one after another both before and after the protagonists’ long trans-Atlantic voyage. But in terms of their function in the plot, the islands are more or less interchangeable. Their individual importance stands in proportion to the affection that the heroes of this historical and geographical novel have for them. Verne’s love for details—which so impressed the translator of this English-language edition of the novel22—was made possible only by the author’s research, since he had never visited the area himself. It is true that his brother Paul, who had just died two years earlier in 1897, had traveled to the Antilles between 1851 and 1853, during which time the brothers also lost two friends who were living or had lived on the French islands there.23 Before participating in the Crimean War as a naval officer from 1853 to 1856, Paul Verne had begun his military career on a trip to Haiti (which had been independent from France since 1804). There, the French army had hoped that its very presence would discourage the despotic leanings of President Faustin Soulouque, who would become Faustin I in 1852 and who would attempt to extend his rule across the entire island of Hispaniola. The expedition then stopped in Cuba and Martinique. But there is no indication that Paul’s reminiscences had any influence on the action of Travel Scholarships, which in any case takes place a quarter-century later.24

Verne owes most of the historical and geographical information about the six islands visited by his characters to the renowned French geographer Elisée Reclus (1830–1905). Although Verne did not share the anarchist views of his eminent contemporary, he nonetheless held him in high esteem as a geographer who had distinguished himself with his abundantly illustrated New Universal Geography (Nouvelle Géographie Universelle) in twenty volumes (1876–1894). During an interview, Verne acknowledged: “I have all Reclus’s works—I have a great admiration for Elisée Reclus—and the whole of Arago.”25 It was specifically in volume 17 (West Indies [Indes Occidentales], 1891, pp. 837–900), of Reclus’s Geography that Verne found the information he needed about the Lesser Antilles; he even adopted the order in which Reclus’s described the islands. It would be pointless in the context of this Introduction to embark on a word-for-word comparison of the two books, but the borrowings were frequently noted in the novel’s manuscript by the abbreviation “R” (for Reclus), followed by the relevant page number. Further, Reclus is cited in the text of the novel itself, and in such way as to show that Verne had full confidence in the reliability of his source:

The impression of the young passengers, once they found themselves in the middle of the port, was exactly like the one Elisée Reclus details in his well-documented Géographie. They thought they had arrived at one of England’s ports, Belfast or Liverpool. There was nothing of what they had observed in Saint Thomas’s Charlotte-Amalia, or in Guadeloupe’s Point-à-Pitre, or in Martinique’s Saint-Pierre. As the great French geographer once remarked, palm trees seemed quite foreign to this island. (Part II, chap. 6)

Another lesser-used source was marked in the manuscript by the letter “P”—most likely designating a book about the island of Martinique by Jean-Marie Pardon.26

As usual, Verne’s textual borrowings are numerous and sometimes nearly word-for-word. For him, this practice enhanced the verisimilitude of the narrative, which was of utmost importance to him. Nonetheless, this same practice would undoubtedly be considered plagiarism today. It is rather surprising that no successful legal complaint was ever lodged against Verne by the authors from whom he repeatedly borrowed throughout his lengthy career.27 Verne’s frequent “recycling” has been often noted, but not discussed in detail and not yet satisfactorily explained. It might be that the change in genre—from popular science to fiction—helped to protect Verne from lawsuits, whereas substantial borrowings from other purely fictional novels would have been much more risky. It is also worth noting that the authors of such works of popular science of the period—the aforementioned Reclus, but also Louis Figuier, Arthur Mangin, and many others—were in the habit of copying from each other as well and probably would have had difficulty in proving their own originality, especially in court.

Verne limited himself to geographic descriptions of the Antilles and took very little inspiration for his story from their historical and social specifics. His compatriot Victor Meignan (1846–?), who published a travel narrative about the region in 187828 (the year following that in which Travel Scholarships is set), had blamed his native France for the unresolved social issues of the region. According to Meignan, the “mixing of races” had led to a multitude of gradations between “whites” and “blacks,” creating hierarchical conflicts not just between social groups but also within families.29 Reclus had silently glossed over these social problems by simply lauding the beauty of the Antillean people—an esthetic approach which masks any underlying racism. It is worth noting that, following his example, Verne also abstains from any racist polemic, which was otherwise quite standard and accepted at the time.

Another social conflict emerged when, in order to ensure successful sugar and tobacco harvests, Europeans began to replace emancipated slaves—who, left to their own devices, no longer had any economic value—with imported workers from the Indies and China. Known as “coolies,” they were poorly paid and kept in a state of dependency that effectively reduced them to slavery. The growing problems among these three groups who formed the Antillean populace were far from being resolved in 1877–78 and they still would not be in 1903, but they are alluded to only a few times in the novel.

THE COMPOSITION OF THE CAST

The narrative elements of action and suspense that could not be derived from the geographic context had to come from another source. In Travel Scholarships Verne uses a relatively large cast of characters, which is unusual for most of his Extraordinary Voyages. There are, in fact, three groups of eleven people each, although the first of these groups is eliminated early on when the pirates murder the legitimate crew of the Alert in order to steal their ship. The third group then enters, consisting of nine high school students about to travel to the Antilles on the three-master, accompanied by their mentor, the Latinist Horatio Patterson, and later joined by the sailor Will Mitz for the return journey home. In order to lay their hands on a large sum of money that will be given to the students at the end of their excursion in Barbados, the pirates temporarily delay their deadly intentions and play the part of the murdered crew, paradoxically ensuring their passengers an exemplary voyage.

These elements of suspense, which drive and structure the story, concentrate on two questions. First, will the pirates manage to keep their real identity and sinister intentions secret, or will they be found out? Second, will the students, who suspect nothing and obviously have the reader’s sympathy, manage to escape the horrific fate planned for them? It is out of the question for a Jules Verne novel not to have a happy ending—the public could be assured of that. So the novelist’s art is to sustain readers’ doubts and feed their fears by creating situations that put the two groups’ interests in peril. That the characters’ goals are so diametrically opposed clearly constitutes a weakness of the story’s dramatic action.30

“I cannot give you a hero every year. It is impossible,”31 Verne had written to his publisher, Hetzel père, in reference to North Against South (1887, Nord contre Sud), his novel about the American Civil War then in development. This remark could apply just as well to Travel Scholarships. The two competing groups both feature individual characters who are more elaborately portrayed than the others, but none really fits the role of hero. Among the pirates, Captain Harry Markel, head of the gang, makes an impression with his sangfroid and his capacity to get his band of criminals out of risky situations. Because of his very criminality, however, he is exactly the opposite of a person who would attract the reader’s sympathy; he completely lacks the dark grandeur of a Robur or the fascinating ambiguity of a Captain Nemo.

Among the group of students, only the two French boys, Louis Clodion and Tony Renault, stand out somewhat from the ensemble; but Tony, the joker of the group, distinguishes himself more with clever words than by actions, which is insufficient for a real hero. What about Horatio Patterson, the students’ mentor? Although he is by far the best-described character—his introduction into the story is carefully prepared, he is regularly used for comical scenes, and he is responsible for the final “surprise ending” of the novel—he is nevertheless ridiculous, with his various tics and his obsession with tacking Latin quotations onto every situation, whether fitting or not. Evidently, Verne had tried to create a humorous character in the mold of his geographer Paganel in The Children of Captain Grant (1867–68, Les Enfants du capitaine Grant), but the result is not all that convincing.

The only character who could possibly lay claim to being the true hero of the story, Will Mitz, does not enter the narrative until relatively late in the novel, and he owes his heroism to several twists of fate that happen to play out in his favor. Perhaps significantly, he also stands out from the other characters because of his strong religious convictions. As in previous novels, the various threads of the story prepared since the beginning are destined to converge in the end, where Verne uses all of his narrative tools—suspense, horror, surprise, mystery, plot reversals, and finally humor—to provide his readers with a satisfying denouement.

INTERTEXTUAL AND AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL ASPECTS

In 1974, a European television miniseries was broadcast under the title of A Two Years’ Vacation (Deux ans de vacances).32 In fact, it drew its inspiration not only from the Verne novel of that title, published in 1888, but also from several other Verne novels, including A Captain at Fifteen (1878, Un Capitaine de quinze ans) and Travel Scholarships. The adaptation combined the characters Dick Sand and Captain Hull from A Captain at Fifteen, the “robinsonade” of the shipwrecked young boys on a remote island from A Two Years’ Vacation, and the pirate band that boards and seizes a ship from Travel Scholarships. What might seem at first glance to be an iconoclastic approach to Verne’s work actually shows to what extent many of the Extraordinary Voyages share common elements and lend themselves quite well to amalgamation, at least in a visual format. I would go further and claim that this practice, used in numerous cinematographic adaptations of Verne’s works, reflects the author’s own writing methods, as he filled his novels with intertextual allusions to his own fictional works.

Travel Scholarships is not exempt from this rule, and not only because of its many similarities to A Two Years’ Vacation. Travel Scholarships opens with the awarding of a prize, as did Paris in the Twentieth Century (Paris au XXe siècle) forty years earlier—although that novel remained unpublished until 1994—wherein the main character, the young man Michel Dufrénoy, receives an award for his Latin poetry. Latin is ubiquitous in Travel Scholarships through the students’ chaperone, Horatio Patterson, who fulfills his duties as accountant of the Antillean School with conscientious seriousness. Michel Dufrénoy tries his hand at this same profession, though he fails miserably at it. As for Patterson, he is a reincarnation of the Latin professor Naso Paraclet, who appears in the early short story The Marriage of a Marquis (Le Mariage de M. Anselme des Tilleuls, also unpublished in the author’s lifetime), for which Verne drew on his schoolboy memories.33 Other elements are typical of Verne’s later novels, such as the role of pirates (appearing in The Kip Brothers [1902, Les Frères Kip], with a very similar episode in a tavern at the beginning of the story, and in The Lighthouse at the Edge of the World [1905, Le Phare du bout du monde]) or of the presence of fog at the end (as in The Sphinx of the Ice [1897, Le Sphinx des glaces] and The Tales of Jean-Marie Cabidoulin).

In a more general way, by featuring an idealized school in its pages, Travel Scholarships alludes to the work of a fellow author and rival who was also associated with the Hetzel publishing house and who wrote under the pseudonym of André Laurie. Born Paschal Grousset (1844– 1909), he had played an important role in the Commune of Paris in 1871 and had been exiled, with ten thousand other Communards, to Nouméa in New Caledonia, from where he had managed to escape, taking refuge first in the United States and then in London. During his exile in England, which lasted from 1874 to 1881, he contacted Hetzel and sent him a number of manuscripts, including several scientific-adventure novels. With the twofold aim of helping an exile and avoiding giving Verne an undesirable competitor, Hetzel decided to have some of Grousset’s novels rewritten by Verne. From this collaboration came The Begum’s Millions (1879, Les Cinq Cents Millions de la Bégum) and The Southern Star (1884, L’Étoile du Sud), published under the name of Jules Verne alone, as well as The Wreck of the Cynthia (1885, L’Épave du Cynthia), signed by both authors even though Verne’s contribution was limited to shortening the text, revising the style, and other minor tinkering. This arrangement was only temporary, however, and could not prevent Laurie from striking out on his own and becoming a serious competitor to Verne with a series of scientific-adventure novels that were published in the Magasin d’Education et de Récréation. When the Magasin was featuring Travel Scholarships in 1903, for example, one of Laurie’s novels, The Giant of the Sky (Le Géant de l’Azur) about a magnificent flying machine, appeared alongside. Curiously, Verne reprised the same subject the following year in Master of the World (1904, Maître du monde).

Laurie showed more originality in a series of novels also published by Hetzel in which he presented his readers with different education systems from Europe and around the world.34 In writing A Two Years’ Vacation, Verne had already made use of the first of Laurie’s works, School Life in England (1881, La Vie de collège en Angleterre). Laurie’s attitude in his books is marked by a pronounced nationalism approaching jingoism that placed the “Celtic race” above all others, though he considers other education systems relatively objectively. Although Verne only touches on the question of education in Travel Scholarships, his fictional Antillean School is an internationalist utopia that serves as a kind of a retort to Laurie’s novels. Despite its modest character, this school merits a closer look, and I will return to it shortly.

Jules Verne was not only inspired by other literary texts; for Verne, everything lent itself to being put into words and becoming text: current-events items about politics or crime, the lives of others, as well as the events and concerns of his personal and familial life. Personal memories occupied an increasingly significant place in his novels, particularly those written after 1890. “Memory is far-sighted,” Verne wrote in The Story of My Boyhood.35 Numerous working documents, where he noted the dates of the deaths of those close to him or the names of people met throughout the course of his life, bear witness to this observation. It is clear that these personal elements in his texts had a different meaning for the author than for his readers, for whom they may often pass unnoticed. But the fact of their inclusion raises several questions about the inscription of autobiography in Verne’s narratives. For example, the Assomption, a real ship on which Verne forced his son Michel to embark as a punishment in 1878, appears in The Kip Brothers (Part I, chap. 5). The village of Chantenay, in the Nantes area, where the Verne family had a country house, is recalled in a central episode of The Mighty Orinoco. In The Tales of Jean-Marie Cabidoulin there appear, among others, “two vessels, the Chantenay of Nantes, the Forward of Liverpool, that were left in great disrepair by the desertion of a number of sailors” (chap. 6). The allusion tied to the name of the first ship is already evident; the second refers to a particular episode from The Voyages and Adventures of Captain Hatteras (1866, Les Voyages et aventures du capitaine Hatteras) and the beginnings of Verne’s literary career.

The timing of the action of Travel Scholarships is explicitly given as 1877 in the manuscript. Although this fact is somewhat camouflaged in the published versions, this dating is confirmed by the sale of the island of Saint Barthélemy, which ends the first part of the novel, on August 10 of that year. At that moment Jules Verne was renewing his connection to Nantes, the city of his birth, and lived there for a year until the summer of 1878. His son Michel, before being sent to the Indies, attended the same high school where his father had taken his Latin courses (which were no doubt deadly boring and taught by pretentious professors—recalling the previously cited satire of The Marriage of a Marquis and also Mr. Patterson in Travel Scholarships). It was during this stay in Nantes that Honorine Verne’s grandson, Tony Lefebvre, died in Amiens at just five years of age. Michel Verne had been especially fond of his young nephew. Is it too much to see the reflection of this lost grandchild in the person of the novel’s young rascal, Tony Renault?

The other French protagonist in the story is Louis Clodion, who is “twenty years old, part of a family of ship merchants who settled in Nantes many years ago” (Part I, chap. 2). He visits an uncle in the Antilles who is “a rich and influential grower in Guadeloupe. He lived in Pointe-à-Pitre and owned vast properties surrounding the city” (Part II, chap. 2). This brief biography matches that of a friend of Verne’s—the merchant and art critic Paul Eudel (1837–1911), whom Verne had met in 1861 in Chantenay at his sister Marie’s marriage to the ship-owner Léon Guillon. According to a brief biographical sketch of him published in 1899, “Upon finishing college, he had to abandon regretfully the literary career he [Eudel] had dreamed of, for his family no longer had the resources to send him to Paris to make his start. He then went into business and left for the island of Réunion in 1857 to join one of his uncles, a rich planter and businessman in Saint-Pierre.”36 Returning to Nantes two years afterwards, Eudel later published his autobiographical Souvenirs de voyage (1864). Despite the different French colonies in question (Réunion or Guadeloupe), the facts and the ages of the persons are similar.

A few pages earlier in Travel Scholarships, as if by a surprising coincidence, Verne mentions the family name of the brother-in-law who had introduced him to Eudel: “It was one of the principal merchants of the city [of Marigot on the island of Saint Martin], Mr. Anselme Guillon, who organized this reception” (Part I, chap. 15). The character named is a secondary one, but this name—which never appears anywhere else in the Extraordinary Voyages—nevertheless recalls once more the leading character of the short story The Marriage of a Marquis, Anselme des Tilleuls. Finally, there is the ship Fire Fly that appears near the end of Part I of the novel: its name is the same as that of a ship in a novel published in 1861 by the novelist René de Pont-Jest (1829–1904). Pont-Jest claimed to have taken part in French naval campaigns with Paul Verne in the 1850s. Later, he would unsuccessfully bring a plagiarism suit against Jules Verne—a lawsuit that was first filed in 1877, the year in which the action of Travel Scholarships takes place. It certainly seems that, toward the end of his life, writing was one way for Verne to bring the past back to life and to give his literary oeuvre a personal dimension without going so far as to make it an overt autobiography.

NATIONALISM AND INTERNATIONALISM

If this autobiographical side of the novel might have passed unnoticed by the majority of Verne’s readers, such would not have been the case for the subject that gave Travel Scholarships its topicality at the end of the nineteenth century: the tension between nationalism(s) and internationalism. It was the historian Jean Chesneaux, one of the pioneers of Vernian criticism, who noted in 1971 that

Verne’s demonstration of the artificial, ephemeral and unstable character of territorial sovereignty is carried to its extreme in the case of the Lesser Antilles (and all the more forcibly because here it is a question of colonial sovereignty and therefore doubly questionable). This novel, Travelling Scholarships, is normally regarded as one of Verne’s weaker works—at least by those who do not take the trouble to seek the key to his political thinking. In point of fact, the demonstration is both vigorous and unconventional.37

From the outset, the Antillean School extrapolated a united and peaceful Europe, which was still far from being realized, as two disastrous wars would soon testify in the following decades. This utopian vision, represented by an educational institution that ensures an ideal instruction—“a very practical as well as a very complete education in all matters literary, scientific, industrial, and commercial” (Part I, chap. 1)—is neatly summarized by the organizer of the journey to the Antilles, Mrs. Seymour, who declares to the laureates: “I don’t see here any English, French, Dutch, Swedes, or Danes, no! Only Antilleans, my compatriots!” (Part II, chap. 6). In reality, of course, such an “Antillean” community has never existed, as national interests have always gotten the better of diplomatic agreements. The noble aspirations of the director of the Antillean School “to strengthen and fuse the young men’s diverse temperaments and mixed personalities, which such different nationalities present” (Part I, chap. 1) developed into the ingenious idea of imposing different languages on the students in turn and in equal measure, regardless of the relative importance of their respective nations: “One week, English was spoken; the next, French was spoken; then Dutch, Spanish, Danish, and Swedish” (Part I, chap. 1). This impressive notion recalls the linguistic talents of Professor Otto Lidenbrock, about whom the narrator of Journey to the Center of the Earth declared that “he was reputed to be a genuine polyglot: not that he spoke fluently the 2,000 languages and 4,000 dialects employed on the surface of this globe, but he did know his fair share.”38

This plurilingual ideal strikes an obvious contrast with the author’s personal situation: throughout his whole life, Verne never spoke any language other than French. In 1903, in his old age, however, he agreed to become the honorary president of the Esperantists of Amiens and to propagate the idea of a universal language in a future novel. In order to understand this course of action, which went beyond the internationalism espoused in Travel Scholarships, it is essential to recognize the cultural standing that the French have always attributed to their mother tongue, the loss of which—even in part—was seen as a loss of identity. Since 1890, Verne himself had been a very active proponent of the Alliance Française, a patriot organization whose aim was to disseminate, with obvious political intentions, the French language and culture throughout the world in order to confront the expansion of English and German, especially in the colonies. In the summer of 1903, while Travel Scholarships was being published, Verne began his last novel, Study Trip (Voyage d’études), which was supposed to extol the advantages of Esperanto. In the text, he intentionally poked fun at “those good French, perhaps too patriotic, who consider their language to be superior to any other, able to suffice in all circumstances.”39 Study Trip, like his first novel, was intended to take the reader across the breadth of sub-Saharan Africa. But it remained unfinished: after five chapters of drafts, Verne abandoned the project.

Verne’s attitudes toward internationalism are quite complicated and require a more nuanced analysis. In Travel Scholarships, he contrasts the noble and altruistic internationalism of the boys from the Antillean School against the anarchy and selfishness of the pirates led by Harry Markel, ruthless outlaws who do not respect a single human value and who, as the narrator repeatedly suggests, live in a community of criminality without any national attachment. One remembers in this regard the crew of the Nautilus under Captain Nemo in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, whose members cut themselves completely off from their countries and even create their own artificial language, to bind them together and to separate them from the rest of humanity. Even if Captain Nemo justifies his actions in order to avenge and support oppressed peoples, his half-criminal character remains highly ambiguous throughout the novel. No such ambiguity exists in another Verne novel, For the Flag (1896, Face au drapeau), where pirates from many different nations live in the interior of “Back Cup,” a small island in the Bermudas, and force the French chemist Thomas Roch to attack his own country’s ships with a new, powerful weapon of his own invention. When the narrator of For the Flag insists that “patriotic sentiments … are the very essence of the citizen” (chap. 1), he denounces the absence of such feelings among the pirates, who come together only as a power-driven collective: “But, if these inhabitants of Back Cup are not bound by ties of race, they are certainly so tied by bonds of instinct and appetite” (chap. 9). Although the inventor Roch, driven mad, seems to share these purely egotistical instincts, he recoils at the last moment and refuses to destroy a warship flying the French flag in an international squadron of naval vessels. Even though this novel is easily one of the most patriotic of the Extraordinary Voyages, the moral of the story is still that the common good can only be assured by an alliance wrought between rival nations.

In Study Trip, it can be deduced from the narrator’s comments that Esperanto would not be a substitute for existing national languages. Rather, it would serve as a tool, an egalitarian link to enable better communication and, by extension, better understanding between people of different ethnicities. Even while promoting the utopian ideal of the Antillean School, the narrator of Travel Scholarships remains well aware of the factors limiting its plausibility, given that “Sometimes racial instincts, more powerful than good examples and good advice, won the day” (Part I, chap. 1). In line with nineteenth-century beliefs, Verne considered national character to be a natural trait, and he made use of such stereotypes when describing his characters in Travel Scholarships and in other Extraordinary Voyages: the French are imperturbably odd, the English are proud, the Danish cold and reserved, the Americans energetic but impatient, and the Dutch phlegmatic. In A Two Years’ Vacation, Verne was very explicit about wanting to present his readers with “a band of children from eight to thirteen years old, abandoned on an island, fighting for life amidst passions fueled by differences in nationality”40 (especially between French and English, with the American Gordon playing the part of mediator). These conflicts are much more attenuated in Travel Scholarships and, if they do arise from time to time, they are quickly resolved. Patriotism is considered a healthy and natural attitude so long as it respects other nationalities, but it risks becoming ridiculous or arrogant when it exceeds its limits (consider the exorbitant patriotism of the Frenchman Henry Barrand or the Englishman Roger Hinsdale, for example). Or as Doctor Clawbonny so superbly put it in another Verne novel: “You can’t swim 300 miles, even if you’re the best Briton on earth. Even patriotism has its limits.”41

On a more serious note, the numerous changes in nationality of the Lesser Antilles since the seventeenth century (which Verne dutifully details for each island) make the bloody battles fought over them by European powers appear quite absurd. The novelist juxtaposes the egotistical claims and shortsightedness of humans with the slow and unstoppable workings of nature that incessantly transform the physical organization of the Earth by volcanic forces. This evolution applies just as well to the Lesser Antilles, whose geological condition, for Verne, was nothing less than conclusive:

It is not impossible that the submarine floor, which is coralline in nature, might someday rise up to the surface of the sea through the persevering work of coral polyps or even as the result of a plutonic upthrust. In such conditions, Saint Martin and Anguilla would then form only one island. […] Could they imagine a future time, very distant no doubt, where these islands would be joined to each other, forming a sort of vast continent at the mouth of the Gulf of Mexico, and, who knows! even connecting with the American territories? Under such conditions, how could England, France, the Netherlands, and Denmark maintain their claims to have their national flags on these lands? (Part I, chap. 15)

In the Extraordinary Voyages, volcanic action is an ever-present geological force that mercilessly and indifferently reveals the limits of human power, even when supported by science and industry. Volcanism destroys as it creates and creates as it destroys, as demonstrated by the end of The Mysterious Island and the real catastrophe in Martinique in 1902.

In this global perspective, humanity must always, according to Verne, work out its differences and overcome the conflicts caused by national interests. It is no doubt just a fortuitous coincidence that Verne conserved among his working notes a long article excerpted from an unidentified journal, dedicated to “the Hague Conference.”42 Although this first international peace conference was not able to halt the ongoing growth of military armament among the Western powers, it did manage to set up an international judicial tribunal and establish rules for armed conflicts. The Hague Conference was held from May 18 to July 29, 1899—about the same time as Verne was writing Travel Scholarships.

TEXTUAL VARIANTS

This translation by Teri J. Hernández was based on the final edition (grand in-octavo) of Verne’s Bourses de voyage, although it is not clear that this version is necessarily the most thoroughly corrected one. Comparing the version from the Magasin to that of the in-octavo reveals a highly unequal number of variations: about 630 for the first part and 170 for the second, which might at first seem to be a huge disparity. But a large portion of these corrections are of secondary importance and are undetectable in translation since they mostly concern punctuation, choice of synonyms, and sentence structure. Nonetheless, it is surprising to note that, although the first part published in the Magasin is closer to the manuscript, such as might be expected, the second part of the edition grand in-octavo, by contrast, shows greater resemblance to the hand-written draft, at least for chapters 1–9. This inconsistency might be explained by the hypothesis that the typographers accidentally used an earlier proof for these ten chapters instead of the final one, or that Verne continued correcting the Magasin proofs, whereas the grand in-octavo version had already been given to the printer. However, as noted above, these variations have no significance in the translation itself. In both parts, the in-18 edition constitutes an intermediate state, mostly agreeing with the text of the in-octavo. When a variant might be of real interest to the reader—as is the case for several peculiarities mentioned above—it is listed in the Notes.

Volker Dehs

Trans. Matthew Brauer