Читать книгу Five Weeks in a Balloon - Jules Verne - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеchapter 9

Rounding the Cape—the forecastle—a course on the cosmos taught by Professor Joe—on steering balloons—on searching for air currents—Ευρηκα.1

The Resolute headed swiftly toward the Cape of Good Hope; the sky stayed clear, although the sea was beginning to run high.

On March 30, twenty-seven days after leaving London, they saw Table Mountain outlined on the horizon; located at the foot of a natural amphitheater formed by the hills, Cape Town was visible through the ship’s spyglasses, and the Resolute soon dropped anchor in its harbor. But the commander made a layover only to take on coal; this was a day’s work; the next morning his ship stood into the south to round Africa’s lowermost point and enter the Mozambique Channel.

This wasn’t Joe’s first ocean voyage; he wasted no time in making himself at home on board. Everybody liked him for his spontaneity and high spirits. A good part of his master’s fame had rubbed off on him. Folks listened to him as if he were an oracle, and his forecasts weren’t much wider of the mark than anybody else’s.

Consequently, while the doctor was busy providing clarification in the officers’ quarters, Joe lorded it over the forecastle, where he laid out his own version of things—a procedure followed, incidentally, by leading historians from the dawn of time.

The balloon journey was naturally the topic that came up. Joe had trouble getting some of the diehards to buy into the undertaking; yet once the sailors did so, their imaginations, stimulated by Joe’s anecdotes, were ready to believe anything was possible.

Our dazzling storyteller convinced his audience that after the present journey, folks would go on plenty of others. This was just the beginning of a long series of superhuman undertakings.

“You see, my friends, once you’ve sampled this type of gadding about, you just can’t do without it; so for our next expedition, instead of heading sideways, we’ll go straight up and keep on going.”

“Wow! Right to the moon!” a listener said in amazement.

“Not the moon!” Joe fired back. “Criminy, that’s old news. Everybody heads that way in these things. Anyhow there’s no water on the moon, and you’d have to take along a gigantic supply—and even flasks of air if you plan on breathing.”

“Fine, but can you get a flask of gin up there?” said a sailor deeply enamored of that beverage.

“Not a drop, me hearty. Thumbs down on the moon! But we’ll take a stroll around those pretty stars and lovely planets my master’s often talked to me about. Consequently we’ll start by dropping in on Saturn—”

“The one with the ring?” the quartermaster asked.

“Right, a wedding ring. Except nobody knows what happened to his wife!”

“What! You’ll get as high as that?” a wide-eyed cabin boy asked. “He’s the very devil, your master.”

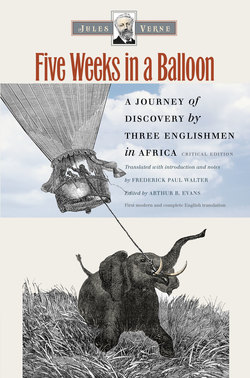

Joe chatting with the sailors

“The devil? Naw, he does too many good deeds.”

“And what happens after Saturn?” asked one of his more restless listeners.

“After Saturn? Well, we’ll pay a visit to Jupiter; an odd locality, mind you, where the days are only 91/2 hours long, which is just fine for slackers, and the years, by jingo, last twelve times longer than ours, which is beneficial for folks who have no more than six months to live. They get a little added bonus!”

“The years are twelve times longer?” the cabin boy went on.

“Yes, laddie; so in those parts your mama’d still be nursing you, and that geezer there, who’s coming up on fifty, would be a little tyke 4½ years old.”

“You’re pulling our legs!” the whole forecastle hooted in unison.

“Gospel truth,” Joe said confidently. “But what do you expect? When folks keep stagnating down here on earth, they don’t learn anything and stay as dumb as dolphins. So head up to Jupiter for a little while and see for yourself! But for pity’s sake be careful on the way, because those moons of his are a pain to bump into!”

And they laughed but half believed him; and he told them about Neptune where seamen get a hearty welcome, and Mars where soldiers hog the sidewalks to the point of tedium. As for Mercury, that’s a nasty world of bandits and merchants who are so similar, it’s hard to tell them apart.2 And lastly he drew them a truly seductive picture of Venus.

“And when we come back from this expedition,” said our genial storyteller, “they’ll award us that Southern Cross gleaming up there in the good Lord’s buttonhole.”

“And you’ll have earned it!” the sailors said.

So those long evenings in the forecastle went by, full of lighthearted chitchat. And meanwhile the doctor carried on with his educational talks.

One day the conversation got around to steering balloons, and they invited Fergusson to give his views on the matter.

“I don’t believe,” he said, “that we’ll manage to steer a balloon. I’m acquainted with all the methods attempted or proposed; not one of them has worked, not one of them is feasible. You can appreciate that I’ve had to spend time on this problem, that it was bound to be of great interest to me; but I couldn’t solve it with the means available from contemporary mechanics. We’d need to come up with a motor that’s both amazingly strong and unbelievably light! And if we did, we wouldn’t be able to withstand air currents of any significance! What’s more, until now we’ve been more concerned with steering the gondola than the balloon. That’s a mistake.”

“But there are major similarities,” somebody countered, “between a lighter-than-air vehicle and a ship you can steer at will.”

“No, there are few to none,” Dr. Fergusson replied. “The air has infinitely less density than the sea, in which a ship is only half submerged, while a lighter-than-air vehicle is fully immersed in the atmosphere and stays motionless in relation to the elastic fluid surrounding her.”

“So you think the science of air travel has nothing more to offer us?”

“Not at all! It just needs to look for different answers, so if you can’t steer your balloon, at least you can keep her in favorable air currents. The higher we go, the steadier they are in their speed and direction; they aren’t troubled anymore by the valleys and mountains that crisscross the earth’s surface, and these, as you know, are the main reason that the wind shifts and blows erratically. Now then, once these different zones have been identified, all the balloon will have to do is get situated in the currents that suit her needs.”

“But in order to reach them,” Captain Pennet went on, “you’d have to go up and down continually. That’s the real difficulty, my dear doctor.”

“And why, my dear commander?”

“Let’s be clear on this: it would create difficulties and obstacles for journeys of long duration, if not for little day trips.”

“And your reason, please?”

“Because you rise only if you drop ballast and you descend only if you let out gas, and in the process your supplies of ballast and gas would soon be used up.”

“My dear Pennet, that’s the heart of the matter. That’s the single difficulty science needs to go forth and conquer. This isn’t about steering a balloon; this is about moving her up and down without sacrificing the gas that’s her strength, blood, and soul as it were.”

“You’re right, my dear doctor, but the problem still hasn’t been solved, the way to do this still hasn’t been found.”

“Begging your pardon, it has been found.”

“Who found it?”

“I did.”

“You?”

“Otherwise, as you can appreciate, I wouldn’t have risked this balloon trip across Africa. I’d be out of gas by the end of the first day!”

“But you didn’t say anything about this in England!”

“No. I didn’t want to become embroiled in public controversy. It wouldn’t have served any useful purpose. I conducted my preparatory experiments in secret and to my satisfaction; so there was nothing more I needed to learn.”

“Well, my dear Fergusson, can you let us in on your secret?”

“Here it is, gentlemen—the way I do this is quite simple.”

Audience interest was at its highest pitch as the doctor serenely took the floor, then spoke as follows: