Читать книгу Five Weeks in a Balloon - Jules Verne - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Verne Takes Off

It’s a balloonist’s nightmare—a nutcase on board …

“The higher we go, the more glorious our death will be!”

All of her ballast tossed out, the balloon carried us to unreachable heights! The vehicle trembled in the air; the tiniest noises became explosions under the arching skies; our planet was the only object that caught my eye in that vastness, and it seemed ready for annihilation, while high above us the sky vanished into deep shadows!

I watched the fellow stand up in front of me.

“The time has come!” he told me. “We must die! All men reject us! They hold us in contempt! Let’s crush them!”

“No more!” I said.

“Let’s cut the ropes! This gondola will run loose in space! The force of gravity will change direction, and we’ll head for the sun!”

My despair galvanized me! I pounced on the maniac, and we grappled hand to hand, struggling fearfully! But he knocked me down, pinned me with his knee, and cut the ropes holding the gondola….1

Verne was in his early twenties when he published the French originals of these lines. They come from a short story entitled “A Journey by Balloon” and they initially appeared in the August 1851 issue of the magazine Musée des familles (Family Gallery). It was only his second story to reach print; the first saw daylight the month before, same periodical, different genre—a Mexican adventure yarn.

Even so, “A Journey by Balloon” is an unsettling performance, among the darkest, fiercest things Verne ever penned. For one thing, it showcases two primordial fears—fear of heights and fear of falling. For another, it marks the debut of a crucial Vernian character—the renegade scientist. The plot is simple but riveting. The narrator, a French balloonist, stages a solo flight in a hydrogen balloon, only to have another Frenchman vault on board right at liftoff. The narrative instantly turns nasty. As the balloon rises into the air, the intruder assaults the balloonist, keeps throwing ballast overboard, and sends the vehicle over three miles up. The nameless skyjacker is dark, menacing, suicidal, apparently psychotic, thoroughly scary. The mix of high-impact fiction and news-making nonfiction seems immediately typical of this author.2

Balloon Beginnings

Human flight was still a new development—it had sprung up nearly full blown less than seventy years earlier and had barely changed in the decades since. The time was late in 1783. “Only rarely,” historian Richard Hallion writes, “do revolutionary systems and technologies appear within the same year, but such is true of the balloon: the practical balloon constituted the dual invention of the papermaking brothers Joseph and Étienne Montgolfier and scientist Jacques Alexandre César Charles” (47).

The first launched the hot-air balloon, the second the gas balloon.

On October 15, 1783, the Montgolfiers sent their first man up in a hot-air balloon, a tethered flight—i.e., the balloon was literally on a leash. On December 1, 1783, Professor Charles went up himself in the first hydrogen balloon—an untethered journey that covered some twenty-five miles and ultimately climbed to 9,000 feet. Charles had recognized “that one could fly by creating a balloon filled with a lifting gas … namely the 17-year-old discovery hydrogen” (Hallion, 49). Isolated in 1766 by British chemist Henry Cavendish, hydrogen went by the nickname “flammable air,” ranked as the lightest of gases, and offered the greatest lifting potential.

Furthermore, Charles’s balloon was a surprisingly advanced vehicle: “a pattern of fishnet-like netting surrounded the upper hemisphere of the balloon … to form an attachment point for support ropes holding the ornate crew gondola” (Hallion, 56). As for the balloon’s envelope, Henry Dale writes that Charles had “constructed a balloon of silk [which was] made impermeable to gas by varnishing it with dissolved rubber. They filled the envelope through lead pipes by adding sulphuric acid to iron filings which, in the process of oxidizing the iron, produced great quantities of hydrogen gas” (12).

Immediately these became the standard procedures, the same measures staying in force for many decades. As chapter 11 of this book reveals, not much had changed by Verne’s day: the lifting gas in his fiction is invariably hydrogen. In fact, as George Denniston sums it up, “Hydrogen-filled balloons … became the balloons of choice throughout the world for almost two centuries” (16).

But if the procedures remained the same, so did the shortcomings. “The two big problems of lighter-than-air flight were propulsion and steering,” as Dale notes (22). “Until they were resolved, the balloon for the most part remained a hobby for the rich and a fairground attraction for the masses rather than a practical vehicle for carrying passengers or freight.”

Fledgling Flier

That’s where things stood when Verne took on the topic of flight as a would-be author. High adventure and exotic locales had intrigued him from his boyhood—he grew up in the French industrial town of Nantes on the Loire River, a quick hop upstream from a busy Atlantic seaport. By then the machine age was well under way, steam-powered locomotives and ocean liners were practical parts of the culture, and flights by gas balloon were a major curiosity.

Samples of Verne’s boyhood writing survive from his teens, including an unfinished novel from his eighteenth year (Herbert Lottman, 17). By the time of “A Journey by Balloon,” he was twenty-three and had just broken into public print. Over the 1850s the Musée des familles published three short stories and two novellas by him, pieces in multiple genres: two tales of dark science, two Latin American adventure sagas, and a manhunt in the polar regions.

He was busier as a scriptwriter, although still not earning much. Over that same general period Verne penned some twenty plays and librettos, notably slapstick farces plus books and lyrics for musical comedies. His first professionally staged work, The Broken Straws, had a Paris run of about a dozen performances in 1850.

More than a decade would go by before Verne earned both fame and decent sales, so he was still a fledgling when “A Journey by Balloon” ap peared. As indicated, it’s a disturbing performance. Threats to life and limb throb under every paragraph, giving the tale unusual tension and ferocity. Verne’s grip is so firm, the reader stays with him even through long stretches of expository material—in fact these educational digressions are almost a respite from the multiplying dangers, from our visceral fears. So as the intruder grows more crazed and the vehicle keeps climbing, we learn about early ballooning … its value in wartime … and its bloodcurdling failures, falls, and death tolls.

A dozen years later, several elements in this early story would be recycled in Five Weeks in a Balloon:

• The vehicle is a hydrogen balloon.3

• The skyjacker claims he has a way to steer balloons.

• Sophie Blanchard’s death is described in detail.

• Likewise the flight of Garnerin’s balloon to Rome.

• At the climax the gondola is cut loose.

• The narrator clings to the netting and reaches safety.

As for the educational matter on the history of ballooning, this is echoed in similar expository passages in Five Weeks in a Balloon—and of course, in much of Verne’s fiction throughout his career.

In other ways too this powerful little story foreshadows Verne’s later writing. Rejected by the scientific community, the maniacal skyjacker is the first of Verne’s “dangerous scientists … the scientist who presents a serious danger to Nature, to society, and to humanity” (Arthur B. Evans, 1988, 83). He’s the precursor of Verne’s darker protagonists, his villain-heroes—Captain Nemo, the aeronaut Robur, the warmongering Schultze. And the story veers toward science fiction when it daydreams of balloons that are sky palaces, prefiguring futuristic vehicles such as Nemo’s Nautilus or Robur’s schooner-shaped helicopter.

Fans will recognize another old standby when the narrator plays word games with one of Newton’s laws: “Their courage was in inverse ratio to the square of their speed of retreat.” Verne rang further changes on Newton down through the years, sometimes seriously, as in From the Earth to the Moon (1865) … sometimes ironically, as in Captain Grant’s Children (1867) where John hopes a flood rain will have a “duration in inverse ratio to its violence” … and sometimes comically, as in The Earth Turned Upside Down (1889) where a lovelorn widow “feels drawn to scientists in proportion to their mass and in inverse ratio to the square of their distance. And J. T. Maston was so plump, she just couldn’t keep her distance.”

However, it should also be noted that the educational matter in “A Journey by Balloon” tallies with accounts by today’s scientists and historians, which means that Verne did a fair amount of homework. This raises the question: how did he become interested in this topic? Some scholars suggest he was inspired by Edgar Allan Poe’s ballooning tales. Others point to his friendship with aeronaut and promoter Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, professionally known as Nadar. And still others deny he had any interest at all, asserting that “Verne did not like balloons” (William Butcher, 149). Yet this tightly detailed, solidly researched story from 1851 casts doubt on all of these theories.

First of all, Poe couldn’t have been a factor. Jean Jules-Verne (30) reports that his grandfather read the American storyteller “in the years following 1848,” yet young Verne had no English, and Poe’s two ballooning yarns, “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall” (1835) and “A Balloon Hoax” (1844), weren’t available in French until after he had published “A Journey by Balloon.” Translated by Alphonse Borghers, the first Gallic version of “Hans Pfaall” came out in 1853 (Arthur Hobson Quinn, 519); as for “Balloon Hoax,” it appeared in 1856 as part of Charles Baudelaire’s first Poe collection, Histoires extraordinaires (Lottman, 84). Furthermore, Nadar’s influence figures even farther down the road: Butcher (145–46) has him entering Verne’s life in 1861.

A number of Verne’s interests seem to date from quite early on, certainly earlier than some have suspected. Take his fascination with polar exploration: when Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym (1837) first appeared in French translation in 1858, the young author was captivated. But he had already published his own tale of polar exploration, “Wintering in the Ice” (1855), which means that the interest was already there. And so it went with ballooning: he wasn’t drawn to this activity because of Poe’s or Nadar’s influence—he was drawn to them because of a preexisting interest.

But again, where did it come from? Marcel Voisin suggests (135) that another literary figure may have been the catalyst: Paris journalist and poet Théophile Gautier had enthusiasms Verne was to share (Stendhal, Wagner, Poe) and dabbled repeatedly in fiction and drama, stirring in such ingredients as well-made plots, submarines, and the Sepoy Rebellion. Young Verne may have hoped to emulate his career, and it seems significant that Gautier “published in Le Journal of September 25, 1848, an article entitled ‘Concerning Balloons,’ and another in La Presse of December 3, 1850, under the title ‘Balloons’” (Voisin, 136).

One more thing: Voisin adds that Gautier frequently contributed to the Musée des familles “over the years 1840 to 1850.”

Trial Balloon

Beneath all these influences and enthusiasms simmered Verne’s “love of geography and exploration” (Butcher, 148), and he tried his hand a little later at straight nonfiction, a book-length travelogue based on his own wanderings over the British Isles. He finished the narrative in 1860, but it too came to nothing and wouldn’t reach print for another 130 years—it appeared in English as Backwards to Britain (1993). Yet for a writer in love with geography, that era offered his mill plenty of grist. The world was full of unknown realms: both polar regions, South America, Canada, Mongolia, Siberia, Australia, the ocean depths, to say nothing of the moon and outer space. Right then the giant continent of Africa was making news: Burton and Speke had returned from it quarreling about the Nile’s source, and in 1860 Speke had gone back “to prove that he was right.” (Hazel Mary Martell, 30)

It was at this time too that African exploration was shifting into shameless colonialism, all Europe getting into the act. The continent’s own people “were no match for the modern weaponry of the Europeans,” as William Habeeb notes (30). “The French focused on North and West Africa, the British on southern and eastern Africa and Egypt, and the Portuguese on the southwestern and southeastern coasts.” Not to mention the Belgians in the Congo, the Dutch in South Africa, and the Germans in East Africa. Ultimately it all led to the infamous 1884 Berlin Conference, where these factions parceled out the whole landmass for themselves. Not a single African was invited, the conference “gave no consideration to [their] needs and desires,” and European rule persisted through much of the twentieth century (Habeeb, 30–31).

But as for Verne’s career, it was going nowhere. Whether penning play scripts, short fiction, or full-length nonfiction, nothing worked until at last the tumblers clicked into place and he found his own winning combination: science … exploration … showmanship.

In 1862 he wrote a novel about a high-tech balloon trip across Africa.

It was finally his moment. As Evans describes it, Barth, Burton, Speke, Grant, and others were “creating widespread public interest in their continuing exploits. There is no doubt that Verne, conscientious as he was about staying abreast of such developments, saw in these explorations not only the ideal ingredients for his first [scientific novel], but also the strong likelihood of its immediate commercial success” (1988, 20).

This time around he had read Poe beforehand. Peter Costello writes that Verne’s edition of Poe is dated 1862 and that he was critical of the American’s two ballooning stories (70). He elaborated on his concerns in an analysis published a few years later: in Edgar Allan Poe and His Works (1864), he faults these tales for “brazenly transgressing the most elementary laws of physics and mechanics.” As we’ll see, Verne was determined to offer something more believable.

In the summer of 1862 he pitched his new manuscript to Pierre-Jules Hetzel, called by the author’s grandson “one of the greatest publishers France has ever known” (Jules-Verne, 54). Hetzel’s author list included the big names of nineteenth-century French literature: Honoré de Balzac, Victor Hugo, Émile Zola, George Sand, Baudelaire, Alexandre Dumas father and son. But the circumstances of his first meeting with Verne are hazy: it isn’t clear how the young writer got his foot in the door or what took place after he did. Both of Verne’s modern biographers bewail the lack of hard evidence, Lottman complaining that “there’s precious little documentation” (83), Butcher suspecting that the details in earlier biographies might be fabricated: “Since no document has ever emerged, it remains perfectly possible that the biographers invented the whole story” (147).

The exact shape of Verne’s new novel is also uncertain. Butcher even wonders if it was a novel (146–47), speculating that Verne offered the publisher a medley of nonfiction pieces about Africa and ballooning, Fergusson’s adventure being simply a fanciful change of pace. But Hetzel called for revisions, and the author turned them around within two weeks (Jules-Verne, 56), so they hardly could have entailed a sweeping structural overhaul. Besides, there weren’t any such medleys in Verne’s earlier output, just short fiction, a couple dozen play scripts, and a book-length travelogue based on his own traveling. He had never been to Africa, and only later did he undertake a multipart geographical overview—and that was in an emergency and at Hetzel’s behest.

More likely his text closely resembled what we know today as Five Weeks in a Balloon.4 The revisions were in the details, edits, and refinements that could be decently managed in a fortnight. But this too remains uncertain: aside from some scraps of chapters 30 and 36, the manuscript is lost (Volker Dehs, 20–27).

Storytelling Strategies

Even so, the novel is distinctive in its structure. Five Weeks uses two separate strategies that Verne would resort to in many later narratives, although not necessarily together as he does here.

He takes exactly the first quarter of the book (chapters 1–11) to set up his journey. Initially he catches our attention simply by acting mysterious: the opening situation is fuzzy and unclear—we’re curious to find out what in blazes is going on. In fact the yarn has an oddly disjointed, piecemeal exposition: chapter 1 hints at a daring expedition by the scientist Fergusson but gives few details—we know little more than what we can glean from the book’s title page, namely that ballooning and Africa are involved. Then chapter 2 adds that Fergusson will fly east to west across the continent’s midriff … after this, chapter 3 raises the notorious problem of how to steer a balloon … chapter 4 reveals that the trip aims to bridge two recent expeditions … and that’s the rhythm. Later chapters keep adding dribs and drabs, culminating in chapter 10’s by-the-numbers description of its innovative answer to the steering question. Verne has, in short, taken ten chapters to fit all the pieces into the puzzle, and we’re finally ready for liftoff in chapter 11. To repeat: the engine that has pulled us along is our itch to find out

“What’s Going On?”

The remaining three-quarters of the novel have a different drive mechanism—they set measurable goals for the balloonists, goals that tease us with a new question: “Will They Make It?” Fergusson’s first hope is to travel all the way to Senegal on Africa’s west coast … his second is to link up the two earlier expeditions—Heinrich Barth’s to the west in the vicinity of Timbuktu, Burton and Speke’s to the east in the vicinity of the Nile’s undiscovered source.

In those days England held a near monopoly on African exploration, and modern readers may not realize that the German Barth was in the pay of the British: “Barth was a Prussian, but he traveled under the British flag, wrote English for preference, and called himself Henry rather than Heinrich” (Felipe Fernández-Armesto, 344). This isn’t as outlandish as it sounds, since Queen Victoria’s mother and husband were both German-born; Anglo-Teuton relations could hardly have been closer. But the point is: Verne’s hero Fergusson is working to connect the discoveries of two English teams.

A tangent to this objective is a third one that Fergusson tackles fairly early on: solving the age-old riddle of the Nile’s source. As chapters 5 and 11 imply, the fictional Fergusson is in a race with an actual explorer, John Henning Speke. In 1860 the latter had gone back to Africa to settle this issue, which automatically means there are other true-life individuals in the race: Verne and Hetzel are hustling to write and publish the novel before it turns into old news. As Verne scholar Andrew Martin insists, “The main reason for speed in the preparation and execution of the expedition is that it is in danger of being overtaken by events” (36).

The danger didn’t materialize, but in any case both of these storytelling strategies turn up in Verne’s later fiction. If we’re more familiar with the second (Will They Make It?), it’s because his top sellers tend to advertise their objectives right in the title: Around the World in Eighty Days (1872), Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), From the Earth to the Moon. In others the goals soon become clear in the text: The Adventures of Captain Hatteras (1866) is a quest for the North Pole … The Mighty Orinoco (1898) is a missing-person search … The Wonderful Adventures of Mr. Antifer (1894) is a treasure hunt.

As for the first strategy (What’s Going On?), it rarely has to carry the whole narrative. The Underground City (1877) and Robur the Conqueror (1886) start with mysterious phenomena that the novels soon set about explaining. The Castle in Transylvania (1892) takes longer, holding off explanations until the end like your standard-issue whodunit. Even less orthodox is Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas (1870), which nails down the reader’s interest by keeping Nemo, his crew, and their motives shadowy all the way through, prompting me to suggest elsewhere that “these mysteries are the book’s undertow” (Walter, 320).

Five Weeks in a Balloon leaves no loose ends and closes firmly enough, but the novel is also notable for the variety of action and description in its final three-quarters, in the many episodes of the balloon’s actual journey. Verne’s book is episodic, built from individual stories, offering many chances for us to wonder if they’ll make it. Some of these minidramas are one-chapter adventures—the outpost of Kazeh, the towing elephant, the battling cannibals, the ravaging locusts. Lengthier conflicts unfold later on—rescuing a missionary (three chapters), getting trapped in the desert (four chapters), Joe’s disappearance (six chapters), the final sprint to the Senegal River (three chapters). But above them all is that overarching objective of reaching the African west coast.

Other key elements are Verne’s plotting skills and gift of invention, especially his knack for conjuring up tight spots, cliff-hangers, and ingenious escapes—e.g., Joe’s certain doom at the close of chapter 35 … the surprise rescue described in chapter 37 … the “setup” in chapter 34 that makes it all possible. This type of adroitness is often classed as “well-made plotting,” and the term is apt here in the same sense that it applies to the play structures of Victorien Sardou and Henrik Ibsen or the detective novels of Agatha Christie and John Dickson Carr: developments and outcomes are cunningly prepared in advance and, even where surprising or shocking, come off as the logical effects of known causes.

Not unexpectedly, Five Weeks ends with a choice display of exactly this kind of virtuosity. Over chapters 38–43 the balloon Victoria keeps losing altitude and seems certain to crash to the earth. Yet each time we think the end is near, Verne finds another way out, reveals another card up his sleeve: they start by dropping all ballast … emptying water tanks … trying this, trying that … on and on through surprise after surprise. It’s one of Verne’s most entertaining traits, here and in the twists, turns, and trick endings of Circling the Moon (1869), Eighty Days, Michael Strogoff (1876), or The Meteor Hunt (1908).

Obviously Five Weeks was ideal for serializing. Its single-chapter adventures would give readers instant gratification, its cliff-hangers would keep them on pins and needles until the next installment. In fact, according to Daniel Compère, “Hetzel had first thought to issue Five Weeks in a Balloon in a periodical specializing in serializations that he’d published since 1860” (37). Ultimately Hetzel released it in an unillustrated softcover edition, but the following year he launched a new periodical in which Verne serializations would be the centerpiece for decades to come. One of history’s first family magazines, it was a twice-monthly publication named the Magasin d’éducation et de récréation. As the title makes clear, it offered a mix of instruction and entertainment, and it grew into one of “the century’s publishing phenomena” (Lottman, 95–6). Verne deserves much of the credit: he furnished Hetzel with a long series of adventure novels that were spiced with humor, hard science, dramatic derring-do, and visionary speculation. Following their serialization, they were republished in illustrated clothbound editions, and over the decades some sixty books appeared in this deluxe format, Hetzel marketing the franchise under the title Voyages extraordinaires … Extraordinary Voyages in literal translation … Amazing Journeys in snappier English.

Standard Ingredients

It may have been due to the saucy scriptwriting that intervened, but Verne’s first novel is thoroughly different in tone from the dark terrors of his early short story “A Journey by Balloon.”

For one thing, his characters are comedy material. Here, as in much of his fiction, they fall into three broad categories: the brain, the antagonist, and the stand-up comic. And these three—juggled, reworked, recombined, often divvied up—will soon became standard ingredients in Verne’s storytelling.

The resident brain is usually a scientist or pedagogue: Dr. Fergusson is a generalist who knows his medicine, history, biological and physical sciences—a walking encyclopedia with countless facts, names, and dates at his fingertips, as he reveals at staggering length in chapters 30 and 38.

The role of antagonist is played by an old pal of Fergusson’s, the rabid big-game hunter Dick Kennedy. In his case it isn’t a full-time job—he opposes Fergusson’s plans only in the first quarter of the book, is outmaneuvered, and after that turns into a well-meaning comrade.

Finally the stand-up comic provides chuckles, chapter taglines, and man-on-the-street perspectives. As is the case here, he’s often a servant: Fergusson’s valet is a pint-sized acrobat named Joe, who talks sense about giant redwoods (“If you live 4,000 years, isn’t it perfectly natural to be on the tall side?”), adds a little social commentary (“If savages had the same tastes as aristocrats, how could we tell ’em apart?”), and even waxes philosophical (“A hunter doesn’t know what hunting really is till he’s the one being hunted!”)

Shrewdly shuffled around, these roles were revived in other novels soon to follow. For instance Journey to the Center of the Earth has its own threesome, except in this case the scientist is the comic figure, his nephew is the skeptical opposition, and the servant is essentially a mute role. Among further variants, two very different scientists supply the brainpower in Twenty Thousand Leagues, while The Mysterious Island (1874) spreads the three roles over a sizable cast complete with understudies (e.g., Pencroff hands off to Joop). In short, there are endless combinations and permutations, and Verne’s stories seem alert to them all. As for the oddity of Kennedy’s short-lived antagonism in Five Weeks, it too reappears: Captain Nicholl badmouths the scheme to go From the Earth to the Moon, then happily signs on in time for blastoff.

Yet, despite its normally lighthearted tone, Verne’s first novel does darken on occasion, although rarely in the vein of “A Journey by Balloon.” Significantly, the most intense of these moments frame the book’s halfway point: Chapter 20 unfolds a stomach-turning combat between two cannibal tribes; then come the events in chapters 21–23, less bloodcurdling but exceptionally somber for Verne as his heroes try to rescue a young missionary. In fact Verne repeatedly grieves the loss of European lives in Africa: Fergusson’s blunt description (chapter 13) of a typical “surface journey” is troubling to read, and even Joe (chapter 35) finds the exploring efforts of Europeans “senseless and even sad.” Still later, when his employer details the blood-spattered history of African exploration (chapter 38), the doctor’s tagline takes the form of a despairing elegy: “This country … has witnessed the noblest kinds of dedication, for which, all too often, death has been the reward.”

At times Fergusson seems to function as Verne’s spokesperson, certainly he’s our handy source for the information and insights that punctuate the action. Such educational nuggets are also standard ingredients in Verne, including full-scale lectures as in the just-mentioned chapter 38. Fergusson is no less diligent with the hard sciences, devoting all of chapters 7 and 10 to his balloon’s inventive design. Finally, as a change of pace, Verne even has Joe deliver a mock lecture—in chapter 9 the servant delivers a bogus description of the cosmos, discoursing “about Neptune where seamen get a hearty welcome, and Mars where soldiers hog the sidewalks.”

And finally Five Weeks contains pinches of the Vernian ingredient known to most: futuristic speculation. In chapter 16 Fergusson envisions a pattern of mass migrations with Africa emerging as “the center of the civilized world.” We’re not there yet, but another piece of speculation came to pass pretty quickly: in chapter 18 Fergusson and Co. pinpoint the Nile’s source, and it’s much as Henry Stanley confirmed it during the next decade. Prophetic also are the novel’s new ballooning technologies: as Verne’s grandson wrote a century later, “No satisfactory solution had yet been found for steering a balloon” (Jules-Verne, 57). His grandfather’s scheme entails a hydrogen balloon, a double envelope, and a pioneering version of today’s burner. Fergusson’s vehicle rises and descends in order to find air currents heading in the desired direction. In the past this was accomplished only by dropping ballast or expelling gas—but after a while the balloon would run out of both and the journey inevitably grind to a halt. Fergusson’s contribution is a heating system whereby the balloon “would rise to the appropriate altitude when the pilot heated water” (Lottman, xi). Warming up, the hydrogen expands and the balloon will climb; cooling off, the hydrogen contracts and the balloon will descend.

Critics Corner

It sounds simple and it is. Furthermore, Verne has been applauded by some commentators for coming up with an authentic innovation. The mechanism just described seems “to have been an invention of Verne himself,” Costello writes (75), and Walter James Miller agrees that the Frenchman had “invented a new and plausible kind of balloon control” (xv). Even three decades later, Verne scholar Jean-Marc Deschamps concurs: “No balloon in Jules Verne’s time had been equipped with such an ingenious arrangement” (15).

Yet Verne’s contraption makes Deschamps jittery: he labels it “a flying bomb,” marveling that it “never exploded despite the dangers lurking on every page” (15). Butcher likewise calls it a “frightening combination” (147), and naturally enough Verne’s device sounds dubious today: hydrogen has long had a shady reputation, ever since taking the fall for the 1937 Hindenburg tragedy. But Verne’s explanations were probably convincing in his own era when hydrogen was king—certainly Nadar was persuaded (Jules-Verne, 56). These days helium and propane often replace it, although it may be coming back in vogue: some space scientists now blame the Hindenburg fire on other causes, “as hydrogen produces none of the spectacular flames that consumed the airship” (David Owen, 63). In any case Verne’s concept still operates in the burners used by today’s hot-air balloonists: the purpose is still to climb and descend in search of favorable currents.

Other criticisms haven’t always been well founded. Costello worries that Verne “does not seem to have considered how dangerous it would be if any oxygen leaked into the system” (75). And yet Verne repeatedly emphasizes (chapters 10, 12, 19, and 42) that the balloon’s throat is hermetically sealed; further, when Fergusson finally resorts to oxygen for lift (chapter 43), the text explicitly tells us that “he took care beforehand to expel any remaining hydrogen through the valve.”

Jacques Noiray has different doubts: he wonders if Verne’s device is truly original, finding it “oddly similar” (45–46) to a so-called secret method used in an 1857 balloon flight to Algiers by the artist Paul Gavarni. I can find no official confirmation that the trip genuinely took place, but in any case it couldn’t have had much in common with Verne’s novel: Gavarni’s vehicle boasted a propeller, two side-by-side balloons, and the usual release of gas in order to descend. The undisclosed method is alleged to have replaced the lost hydrogen—which makes it an entirely different animal from Verne’s heating system.

As indicated, Verne’s candidate for the Nile’s source has sometimes been called prophetic: he opted for a stream flowing north from Lake Victoria (rather than Lake Tanganyika, as Burton argued). It was a prophecy “fulfilled in a matter of months when John Henning Speke returned from Africa to announce he had discovered the source of the Nile. But Verne’s hero … had already made exactly the same discovery” (Miller, xv). The hard facts leave no wiggle room: Five Weeks in a Balloon rolled off the presses on January 31, 1863; Speke’s famous telegram (“The Nile is settled.”) reached London on May 6, 1863, appearing in the Times on the following day (Benjamin Disraeli, 275).

Given this chronology, it seems bizarre of Martin to disparage Five Weeks by claiming that Speke had found the Nile’s source in 1858, long before the novel and that it was “something which has already been discovered” (35–36). Few agreed back then and few would agree now: as Fernández-Armesto reminds us, Speke “had seen only the southern shore of the lake and had not established how big it was or even whether it was a single body of water” (352). In fact Speke’s later claim in 1863 (after he actually reached the northern end) also met with widespread resistance; it was only in the mid-1870s that an expedition under Henry Stanley “settled the question” and at last confirmed that Speke’s hypothesis was correct (Fernández-Armesto, 355).

Generally, then, Vernians have high regard for Five Weeks in a Balloon. Butcher speaks for many when he notes its “innovative theme,” calls it “a highly readable story,” praises its “variety and pace,” and labels it “quintessential Verne” (147–48). Not surprisingly, the book enjoyed strong sales, effectively launching Verne on a lifetime career. His grandson judged it “an immediate bestseller” (Jules-Verne, 57), while Lottman and Butcher both agree it was Verne’s most successful title after Around the World in Eighty Days: the former (xiii) estimates that it was his second biggest seller in its original edition, while the latter (150) goes even farther: “Over Verne’s lifetime … Five Weeks … [sold] second best among all his books, with an estimated one third of a million copies in French alone.”

Aftermath and Influence

Verne stayed interested in aeronautics. Later in 1863 he joined Nadar in founding “a Society for Aerial Locomotion” (Jules-Verne, 57–58), then helped promote his friend’s manufacture of a colossal balloon nearly as tall as Notre Dame cathedral. Christened the Giant, the vehicle was, in Miller’s words, “one of the greatest publicity stunts of all time” (xiv), since it raised money for Nadar’s aviation schemes while simultaneously boosting sales for Verne’s new novel.

The author waited another decade before he went flying himself: “his first and only balloon flight … lasted only twenty-four minutes” (Lottman, 91). His pilot was the famous aeronaut Eugène Godard, and Verne wrote up the experience in a newspaper article, “24 Minutes in a Balloon” (1873), for the Journal d’Amiens. His verdict on ballooning was positive: “It’s even more than a journey, it’s something like a dream, but a dream that’s all too short!”

This brief account was one of several further pieces by him on the topic. Earlier, Verne had penned two articles for the Musée des familles, one on Nadar’s colossal project entitled “Concerning the Giant” (1863), the other the aforementioned Edgar Allan Poe and His Works, in which he critiques Poe’s ballooning stories. Following his twenty-four minutes with Godard, balloons would again play key roles in his novels (The Mysterious Island, Hector Servadac [1877], Robur the Conqueror), not to mention related gadgetry such as giant helicopters (Robur again), long-range missiles (The Begum’s Millions [1879]), seaplanes on wheels (Master of the World [1904]), even manned kites (A Two-Year Vacation [1888]).

Beyond the aeronautics in Five Weeks, its events, settings, technology, and ethical content were additional influences on Verne’s later fiction. Its side issue of determining the Nile’s headwaters becomes a major objective in another novel about a big river, The Mighty Orinoco. Similarly, the lighthearted bets placed in chapter 2 are warm-ups for many a later wager, sometimes incidental (The Meteor Hunt), sometimes pivotal (Around the World in Eighty Days). In fact the latter dusts off several plotlines from Five Weeks: the rescue of the missionary from homicidal natives is echoed in the rescue of Lady Aouda from Brahman fanatics … the servant Joe gets separated from his master and two story lines advance concurrently, ditto with Passepartout in Eighty Days … and the last-minute dismantling of the balloon Victoria prefigures the climactic burning of the merchant steamer Henrietta.

As for settings, one geographic feature in Five Weeks became a leitmotif in these novels. The Victoria flies over a raging volcano in chapter 22, and this Vernian vision is amplified in most of his books over the next decade—Journey to the Center of the Earth, Captain Hatteras, Captain Grant’s Children, Circling the Moon, Twenty Thousand Leagues, The Mysterious Island … and onward to the volcanoes in late-career titles such as Propeller Island (1895) and Master of the World.

Moving on to technology, the Victoria’s slow death in the desert (chapters 24–27) is the first instance of Verne devising an impressive vehicle, then evenhandedly exposing its Achilles heel (the balloon isn’t self-propelled). A few years later he stages a similar exposé in Twenty Thousand Leagues when the submarine’s single weakness (she can’t manufacture oxygen) creates a life-threatening problem under the polar ice. And comparable things go wrong in Circling the Moon, The Earth Turned Upside Down, and Propeller Island. Verne may have faith in science, but it isn’t blind faith.

Of course the close descriptions of Fergusson’s mechanism are the forerunners of other famous hardware passages in these novels: the development-by-committee of the space capsule in From the Earth to the Moon … the specs on Nemo’s diving gear in Twenty Thousand Leagues … the disquisitions on aerodynamics in Robur the Conqueror. But Five Weeks also offers another shrewd insight: men bond with machinery. As Alain Froidefond observes, Verne “eliminates or renders inaccessible female heroes as often as possible, instead giving a primal role to the machine” (24). Sure enough, the balloon Victoria is literally the love interest: “I’ve gotten attached to her,” Joe admits in chapter 41. “It’ll be hard to part with her!” Then at the close when she sinks into the Senegal River, he moans “Poor Victoria!” while even the doctor “couldn’t keep back a tear.” And this moist moment won’t be the last in these novels. In The Sphinx of the Ice Realm (1897), when the stoic first officer sees his ship go down, Verne writes: “He was a man of the sternest fiber, and yes, he wept.” Or in The Steam House (1880), when the robot elephant meets its explosive doom: “Poor creature!” the inventor says, and then follows up with “a huge sigh.”

Five Weeks also introduces a number of ethical issues that are often debated in later books. One, Verne’s pacifism, is only hinted at in chapter 20, where, as usual, Fergusson seems to be the author’s mouthpiece: “If our supreme commanders could look down on their fields of operation as we’re doing now, maybe they’d ultimately lose their stomach for blood and conquest.” But two other issues get more extended coverage in Verne’s first novel.

Greed and gold are the first. Kennedy leads off: early on he kills an elephant, damages one of its tusks, and bemoans the loss of thirty-five guineas. But the most biting passages are in chapter 23 and involve the valet Joe squabbling over gold deposits with Dr. Fergusson, who reveals an unsuspected gift for deadpan comedy. In essence Joe has great difficulty deciding between keeping his gold and dying of thirst, and this form of insanity is a thread Verne will follow repeatedly—mid-career in Hector Servadac and The Earth Turned Upside Down, near the end in The Meteor Hunt and The Golden Volcano (1906).

But ecological concerns seem to arouse Verne’s deepest anxieties, and there are several caustic passages in Five Weeks. Dick Kennedy figures in most of them, a hunter so obsessed with his firearms (chapter 42) that he would rather finish the trip on foot than give them up. Elsewhere (chapters 28 and 31) he can’t remember his kills and lives only for the next one—as an old adage on addiction puts it, “A thousand aren’t enough.” Finally in chapter 31 Fergusson reprimands him: “what’s the point of shooting animals you can’t make use of?” he asks the Scot. “To slay an antelope or gazelle for no good reason other than to satisfy your everyday hunting urges—that really isn’t justified.”

Verne takes up this environmental cudgel again in Twenty Thousand Leagues, accurately predicting the near extinction of many marine mammals. Here Kennedy’s stand-in is Ned Land, a Canadian harpooner; when Land wants to attack a pod of inoffensive baleen whales, Captain Nemo’s refusal expands on Fergusson’s reprimand: “It would be killing just for the sake of killing…. When your colleagues, Mr. Land, destroy decent, harmless creatures like the southern right whale or the bowhead whale, they’re guilty of criminal behavior … and they’ll ultimately wipe out a whole class of beneficial animals.”

Translating for Today

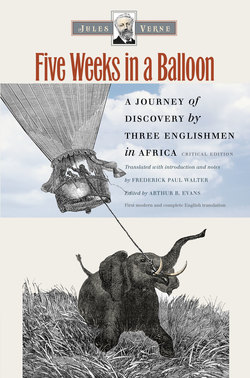

Even in the twenty-first century, then, Five Weeks in a Balloon is a novel with a good deal going for it:

• It’s Verne’s first novel, his breakthrough book.

• It was his second biggest seller, after Around the World in Eighty Days.

• It launched his famed series of Voyages extraordinaires.

• It’s the classic ballooning novel.

• It’s the first steampunk story.

• It’s a triple-threat mix of adventure, comedy, and hard science fiction.

• It wrestles with ecological and economic issues that are still unresolved.

The present Wesleyan edition is the first complete English translation of this seminal work. It’s not, however, the earliest translation in our language: the immediate popularity of Five Weeks led to the rapid publication of several English versions—nearly all in Verne’s lifetime, during the high noon of his fame. As Evans reports in “The English Editions of Five Weeks in a Balloon” at the website Verniana, there have been six prior translations of this novel: three identify their translators (William Lackland, Frederick Amadeus Malleson, and Arthur Chambers), the other three keep them anonymous (the publishers are Chapman and Hall, Routledge, and Goubaud).

A seventh, much later version appeared in the 1960s under I. O. Evans’s byline, but it proved to be an abridged spin-off of the Malleson rendering. Nor, alas, are any of the other editions responsibly complete. The Chapman and Hall text eliminates a good quarter of the book and goes to the rear of the class; Malleson, Routledge, and Goubaud condense almost every chapter, while Chambers’s 1920s rendering often slurs details, seemingly out of carelessness. Lackland’s is the fullest text, yet it has its problems too: the author’s many footnotes are omitted, and there are a variety of small mishaps—dropped lines, missing details, technical errors, fleeting mistranslations, unnecessary glosses, etc.

Beyond these questions of omitting and condensing, there are language and style issues—severe ones. True, these are texts from another time and place, so reading them will naturally grow more difficult as the years go by. But they also present an uglier language barrier: in dealing with Africa and its peoples, these old British editions—Lackland’s included—resort to racial epithets and pejorative slang, allowed in their day, despised in ours. Yet Verne’s French is neutral and restrained, so as Evans concludes elsewhere (2005), the fault lies with the translators themselves: had they “chosen to be more faithful to what Verne had originally written, such terms would never have found their way into the English versions of [this novel] in the first place” (96).

So a complete, accurate, reader-friendly translation of Verne’s early masterpiece is long overdue. This book has a twofold audience: first, the countless general readers who think Verne is fun to read, a population ranging from school kids to scientists to oldsters with fond memories. This new translation is particularly meant for them and works to balance the two methodologies Kieran O’Driscoll describes in his recent study of Verne in English: in brief, my text began life as a “highly accurate, source-oriented, imitative” rendering, which I then polished using “informal, idiomatic language” (251–52). As for other audience members, they include the growing battalions of scholars and specialists who, although they know their Verne from the original French, are still appreciative of textual detective work and stimulating critical materials. I encourage them to consult the endnotes, which address the policies, priorities, textual puzzles, and interpretive decisions affecting the translation. In short, to borrow another of O’Driscoll’s phrases, this new, complete rendering of Five Weeks in a Balloon is “aimed at both a general and a scholarly readership” (190).

Frederick Paul Walter Albuquerque, New Mexico

REFERENCES

Butcher, William. Jules Verne: The Definitive Biography. New York: Thunder’s Mouth, 2006.

Compère, Daniel. Jules Verne: Écrivain. Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1991.

Costello, Peter. Jules Verne: Inventor of Science Fiction. New York: Scribner’s, 1978.

Dale, Henry. Early Flying Machines. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Dehs, Volker. “Les Manuscrits de Cinq semaines en ballon.” Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne, no. 183 (August 2013): 20–27.

Denniston, George. The Joy of Ballooning. Philadephia: Courage Books, 1999.

Deschamps, Jean-Marc. Jules Verne: 140 ans d’inventions extraordinaires. Paris: Du May, 2005.

Disraeli, Benjamin. Letters: 1860–1864. Edited by M. G. Wiebe, Mary S. Millar, Ann P. Robson, and Ellen L. Hawman. Toronto: University of Toronto, 2009.

Evans, Arthur B. “The English Editions of Five Weeks in a Balloon.” Verniana 6 (2013–14): 141–70.

———. Jules Verne Rediscovered: Didacticism and the Scientific Novel. New York: Greenwood, 1988.

———. “Jules Verne’s English Translations.” Science Fiction Studies 32, no. 1 (March 2005): 80–104.

Fernández-Armesto, Felipe. Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. New York: Norton, 2006.

Froidefond, Alain. “Jules Verne fabuleux.” In Jules Verne, no. 8: Humour, ironie, fantasie. Edited by Christian Chelebourg. Paris: Lettres Modernes Minard, 2003.

Habeeb, William Mark. Africa: Facts and Figures. Philadelphia: Mason Crest, 2005.

Hallion, Richard P. Taking Flight: Inventing the Aerial Age from Antiquity through the First World War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Jules-Verne, Jean. Jules Verne: A Biography. Translated and adapted by Roger Greaves. New York: Taplinger, 1976.

Lottman, Herbert R. Jules Verne: An Exploratory Biography. New York: St. Martins Press, 1996.

Martell, Hazel Mary. Exploring Africa. New York: Peter Bedrick, 1997.

Martin, Andrew. The Mask of the Prophet: The Extraordinary Fictions of Jules Verne. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990.

Miller, Walter James. The Annotated Jules Verne: From the Earth to the Moon. 1978. 2nd ed. New York: Gramercy Books, 1995.

Noiray, Jacques. Le Romancier et la machine: L’image de la machine dans le roman français, 1850–1900, vol. 2. Paris: Corti, 1992.

O’Driscoll, Kieran. Retranslation through the Centuries: Jules Verne in English. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2011.

Owen, David. Lighter than Air: An Illustrated History of the Development of Hot-air Balloons and Airships. Edison, NJ: Chartwell, 1999.

Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1941. Pbk. ed., 1998.

Voisin, Marcel. “Théophile Gautier: Précurseur de Jules Verne?” In Colloque d’Amiens (1977), vol. 2: Jules Verne: Filiations.Rencontres.Influences. Paris: Lettres Moderne Minard, 1980.

Walter, Frederick Paul. Amazing Journeys: Five Visionary Classics by Jules Verne. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2010.