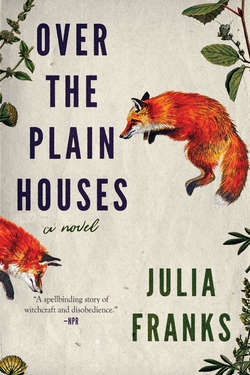

Читать книгу Over the Plain Houses - Julia Franks - Страница 10

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

THAT EVENING IRENIE SCRAPED THE LEAVINGS FROM the dishes and promised herself to do it. There was no good in waiting. She didn’t even have to mention Mrs. Furman.

Brodis was leaning against the back of his chair, a penny already gripped between his thumb and index finger, now tapping absently against the tabletop. For years, he’d been paying Matthew a cent for each passage, though she and he both knew it wasn’t the money that mattered. It was the ceremony the boy wanted, Brodis taking the coin from the glass jar, his hand holding Matthew’s while the other pressed the penny into the boy’s palm, Brodis peering all solemn into his son’s face.

Good job.

This evening her husband seemed relaxed. He was even humming, tapping and humming. Then out of nowhere his mind seemed to circle back to something he’d forgot to be curious about. But his question was loose. “What did you and that agent talk about yesterday?” From the sound of his voice, he hadn’t even turned around.

Irenie stopped scraping plates. Then, before she had time to make a plan, the answer slid right out of her. “Matthew.” As if she’d been telling fibs all her life. “We talked about Matthew.”

Her son yanked his head in her direction, waiting for more.

“She said you were one of the most intelligent boys she’d ever met.”

Did her son really and truly straighten or was it something she couldn’t help but imagine? Either way it was a great new pleasure, this ability to bequeath to him a stranger’s admiring words.

Brodis grunted. “We didn’t need a outsider come from another state to tell us that.”

The boy flushed from his collarbone straight up to his hairline.

Brodis didn’t seem to notice. “Besides. It only struck her that way because it wasn’t what she expected to find here.” It was only one sentence, but somehow it made everything she’d tried to do smaller.

“You think she’s judging us.”

“I do. She may know how to teach reading and toothbrushing, but it don’t mean she knows how to live better than other people.”

And she might have said it then, fertile ground or no. But it didn’t seem fair to bring it up in front of Matthew. There was never a time when he wasn’t paying attention.

Brodis wasn’t finished. “And she’s going to want the same as everybody else from a distance, same as the missionaries or the census takers or the regulators or anyone else from the government. Every single one of them wants you to change in some way.”

As if he already knew what Irenie was going to ask. As if he were closing the door before she even got to the threshold. But there was still time. Wait until they’d both undressed and slid under the quilts. She could bring it to him then, like a gift she hoped he would receive. And he might. He might.

Now Matthew folded his arms behind his back and lowered his head, his eyes watching his father from beneath his lashes. His hair was so fair that his brows blazed white against the pink of his skin. And already he was tall. Already the floorboards jumped when he walked across the kitchen to lift the lid of the stew pot and ask what was for dinner.

Brodis cued him. “All right.”

Irenie turned back to the sink and reached for the next plate on the stack.

“In my Father’s house are many mansions.” Her son’s voice was as slim as a girl’s, flinching when it stood before Brodis. Tonight it seemed especially thin. “If it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you.”

Her husband was still, a man who was never in a rush. He was preaching in three churches each month now, with tent revivals and camp meetings in the summer, and there were those who came specific to hear him. But a strange thing happened when a man reached the place he was trying to get. His thinking set, like a churn of milk gone to butter. It took the shape it was going to take, and there wasn’t a thing in the world that was going to change it short of melting or breaking into pieces either one. It was what it was. Only a man whose believing had hardened to certainty would turn in his wife’s cousin for making stump whiskey. Only a man who was sure of his place next to Jesus would have drawn a map and marked the location.

Matthew’s voice floated toward the ceiling boards above his father’s head. “And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again. And receive you unto myself.”

Brodis grunted the way a man did when the evidence in front of him confirmed everything he already thought. And when she’d said it was only a bit of liquor and that it was more hobby than business, he’d told her she’d do better to stay away from the issue on account of her moral judgment being clouded anymore.

That was years ago. It was the first time she’d noticed herself receding. Even then it was more like a recognition of something that’d been happening for a long time, a kind of drawback, the way a lake sank down in a dry spell, shrinking into itself bit by bit, and so slow that you didn’t notice it—until one day you looked up and there was your husband, the same beautiful and forthright man he’d always been, but so far away up the bank that his shape could be the shape of anyone. And him not noticing how wide the distance had become.

Instead she stayed alert among other women, hoping to hear that the shrinking wasn’t happening to her alone. But most of them talked about other people, not themselves. If they had a name for the hurt she felt, they weren’t telling it in public. Or maybe they didn’t have the energy to ask questions, whenever every bit of effort went to the feeding of mouths. And maybe one day they looked up to find their lives had fled them.

Matthew’s voice quavered and rushed. “I am the way, the truth, and the life.” But something was different, as if some other task urged him forward, as if he’d already seen the new-built school. As if he knew too that every boy there would have read Treasure Island as many times as he had, that they too had stashed the book under their pillows for months before returning it late to the library. “No man cometh unto the Father but by me.”

Irenie turned from the sink.

Brodis seemed to sense a difference too because he nodded and said something that sounded like, “Getting too easy for you now.”

And perhaps it was that break from routine that gave their son permission to say it, the boy taking the opening that his father had given him. “Daddy?”

“What.” The word that ought to have ended on an upswing finished flat as a command.

“I have a question.” Her son looked bright and quick, the same way he’d looked whenever he’d discovered the arrowheads, impatient to show her the thing he’d spied half buried in the earth. And for a moment, she felt it too.

For a moment. But she’d already pre-planned the conversation about the school. She didn’t want to wait another day. She gave her son a hard look, but the boy’s attention was on his father.

Brodis’s tone was bored, as if he’d already heard every question there was to ask. “What is it.”

Her son seemed to straighten. “When he says no man cometh unto the Father except by me, that means that you got to have Jesus in order to get into Heaven, right?”

“Unh huh.”

Matthew’s eyes skipped from his father to the table and back. “What I don’t get is the part in Luke where the lawyer—.”

“What part in Luke?” Brodis’s voice quickened. Irenie couldn’t see his face, but she could guess the walled expression there.

“Chapter ten, I think twenty-five or twenty-six, where the lawyer asks him how to get eternal life.” Matthew’s eyes swept the table now, and Irenie willed him to change his mind. The desks in the new school would be golden with linseed oil varnish, their surfaces uncarved and unblotted. Whatever the question was, it wasn’t worth it.

But Matthew didn’t check himself, and when he opened his mouth to speak again, she felt alarm, but also pride. “And Jesus answers that the way, the way to get to Heaven is to love God and your neighbor. He doesn’t talk about how you have to, you have to go through Him to get there.”

Brodis didn’t move.

Uncertainty flickered into Matthew’s eyes. “Through Jesus, I mean. How come He didn’t tell the lawyer that he had to go through Him?”

A moment passed and Irenie realized she was holding her breath. The kettle on the stove hissed, and she poured the water too fast into the dishpan. The steam rose up in a cloud.

Matthew pressed ahead. “Or likewise whenever Mark says, you know, that he, that he who believes in God and is baptized shall be, shall be saved, and he that believes not. . .”

The sound of Brodis’s sigh cut him off, then the thud of his boots hitting the floor, the creak of the chair as he came to his feet. Brodis reached into his pocket and withdrew an object Irenie couldn’t see but guessed to be his pocketknife. When he held it out to his son, she saw that she was right. He opened it with his thumb and turned it handle up. “Take this.”

Matthew took the knife, hope and confusion raising up his features.

“And go on out there to the edge of the yard and cut you a switch.”

For the first time, the boy looked at Irenie. Her response came unbidden before she thought to make it, an immediate and tiny shake of the head. Don’t say no.

Matthew’s features collapsed, and he didn’t look her way again.

But Brodis must have noticed, because he stood and looked around. Irenie turned back to the sink so that her husband wouldn’t spy the anger in her face. Nobody said anything.

Then the door opened, and the cold blasted into the room.

“Come back here,” Brodis barked.

The door widened and Matthew’s face appeared. “Sir?”

“Get your coat.”

Matthew did. The latch clicked shut behind him. Only then did Irenie seize the minutes. “Brodis. . .”

His stare made her tiny, his answer immediate and swift. “Foolishness is bound up in the heart of a child, Irenie.”

There’d been a time she’d tried to tell him about the receding, and the way the lake shrank into itself. But he’d looked at her so squarely that she’d stopped. “You’re keeping the bad,” he’d said. “You’re nursing it.” And it might be he was right. Maybe she was saving the wrong things, like the memory of the little girl buried in the tiny pine box. Either way, she couldn’t see confiding in him.

But now she made herself say it. “For asking a question?”

His eyes pinioned her to the drain board. “His heart ain’t right, Irenie.”

Irenie stared back. It wasn’t true. There wasn’t a thing in the world wrong with the heart of Matthew Lambey. But before she could say so, the door opened, and her son entered, a look of woe on his thin features. He laid the switch on the table.

Brodis sat down. In place of looking at the switch, he spread his knees and put his hands on them, bending his face toward the floor as if lost in contemplation. After a moment, he looked at his son. “Look here, Matthew. You’ve been grubbing potatoes ever since you was this big.” He held his hand parallel to the floor. “You know that whenever the furrow is cracked good and deep it’s something there. So you dig. And you might get a fair size potato or might be a medium one or sometimes you get only a small one. But you dug it up and now you got it. Can’t put it back in the ground. Can’t say, ‘I don’t like this potato because it’s too skinny or too round or too ugly and got too many black spots.’ No. You take that potato because that’s where your sustenance comes from. That’s your food. You take it and you’re thankful because without it you’d die. Only a stupid man throws the ugly potatoes away.”

Matthew was still standing, eyes sliding toward the wood stove. “Yesser.”

“And only a prideful man refuses the potato with the blackened eye.”

“Yesser.”

“But that’s what you’re doing with God.”

“Yesser. . .” Matthew didn’t sound convinced. His eyes skipped from the stove to Brodis to Irenie and back again to this father. “Sir?”

Brodis cut him off in a dead level voice. “No. You wanna take the parts of the gospel that are fat and smooth-skinned and pleasant and keep them for yourself. And you wanna throw the disagreeable parts away.”

“I don’t wanna throw them away. I just thought they were supposed to—”

“And you’re finding disagreeables because you’re looking for them. You’re grubbing in that potato patch expecting to find black ones. Looking to find something ugly. God’s word is like anything else. If you expect to find something you don’t like, that’s exactly the thing you’ll find.” Brodis scrutinized his son’s face.

“Yesser.”

“There is a way that seemeth right unto a man, but the ends thereof are the ways of death.”

“Yesser.” Matthew’s eyes flickered from his father’s face to the floor and back again.

“The Kingdom is set up in the heart of the people.”

“Yesser.”

“Not in their heads.”

“Yesser.” Eyes on the floor.

“I know that there are some like your Papaw believe you have to bend your faith in order to get along in the real world. He calls it compromise. But that don’t hold water with the Lord.” Brodis paused and reached for the switch. Then he waited for his son to look up. “You see this?”

“Yesser.”

Brodis flexed the switch. “Bends, don’t it?” He pulled the ends closer to one another.

Matthew looked worried.

“Bends pretty far, don’t it?”

“Yesser.”

“The more you bend it, the easier it is to bend a bit more.” The stick was almost doubled now. Brodis touched the two ends. “What was once straight now goes both ways. A direct contradiction.”

“Yesser.”

Brodis squeezed the two ends together. The stick made a cracking sound and began to splinter. “See that?”

“Yesser.”

And still Brodis flexed. “Just about broke in two but it still bends.” More cracking. The green fibers resisted until they couldn’t. The pith split. A thread of bark held the two pieces together. “Come here.”

“Yesser.” Matthew stared at the splintered stick, an expression of alarm on his face.

Brodis proffered the fractured limb and peered into his son’s face. “There’s all manner of people out there who’ll tell you how to believe.” He almost sounded as if he was pleading. “But you gotta understand. The thing you’re compromising is your own soul.”

The features in Matthew’s face had widened and spread. “Yesser.”

“Comes a point when a man can’t tell the difference between a bending and a breaking.”

“Yesser.”

“And you know and I know that the scriptures come from the Almighty. If He was to be mistook about Heaven, then He could be mistook on anything. And then why would we believe His gospel at all?” Brodis gripped Matthew by the shoulders. “If a man can’t hold true to his believing on the small stuff, how can he hold true on the stuff that really matters?” There was an undercurrent in his voice that Irenie couldn’t name, something that in another man she might have identified as fear.

Matthew didn’t answer.

“If you can’t accept the details on faith, what’s gonna happen whenever the Lord asks you to do something difficult? You’re gonna start asking Him about the particulars?”

Matthew said nothing. These were not questions for answering.

But Brodis seemed to want to hear the answers anyway. He set them out without apology. “You’ll never become a firm kind of man, that’s what. You’ll be one of those fellows who can never decide. And no one will ever trust you to make a hard choice.”

Irenie turned back to the sink, slid the scraped dishes into the dishpan without making a sound, poured the bucket of cold well water into the dishpan. The steam dissipated instantly.

The linseed-oiled desks seemed a long way away.