Читать книгу Over the Plain Houses - Julia Franks - Страница 9

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

IRENIE PAUSED ON THE PORCH TO LISTEN. IT WAS PAST midnight. She pulled shut the door and held her breath against the likely of whining hinges. If he was to rouse, she could say that her bowels had run away with her and she was headed to the privy.

She eased the latch into place.

The night air was an ally: sharp, alive, alert. She stretched her hands into the army overcoat and pushed the eagled brass buttons through the holes.

Best to wait one, two, ten minutes, in case he had waked. Ice skinned the washing tub, and frost dusted the stacks of wood, the cut and the uncut, both of them outsized by the great frosted pile of coal. And the new school glowed up hot in Irenie’s mind. Though she’d kept it to herself all day, she hadn’t for a moment forgot it was waiting, like a live fire hiding under a heap of ash in the morning fireplace. You slid the shovel under the gray until you heard the grate of iron on stone. Then, when you flipped it, the coal kindled up orange in the dark.

She listened. But there was only the ghost of her own breath hanging in the stillness, and beyond that the persistent march of water from the springhouse to the branch, its hurry to the base of the mountain, to the place where it joined the river under the white arms of calicoed sycamores. Scram and Lacy and Stomper opened their eyes and watched, but it was the redbone Fortune who lifted her head and cocked her ears. Irenie considered the dog for a moment but motioned her to stay. On warmer nights, yes, but not now.

Winter didn’t need dogs. The earth was packaged yet, drum-tight. Its creatures still slept, the white-footed mice curled into the cracks of the barn, the voles buried beneath the beech leaves, the yellow-painted box turtles drawn up tight under winter-rotted logs, the snakes like hairballs in the roots of trees. Likewise the bears suckling their newborns high in the silver-lichened beeches—and her son sleeping his odd, fitful sleep, clutching and unclutching. The world was hers, at least for an hour or two. Brodis was safe accounted for in their bed, under the quilts she’d sewn, dreaming virtuous dreams.

It was strange. She’d married him in part because he’d seen the world, and she’d thought a life with him would open her up too. But somehow the opposite had happened. They’d set up housekeeping so close to home that the land was part of her great grandfather’s original parcel, and to this day she hadn’t figured out how the wide place that had been her growing up had shrunk so tight that she found herself lonely in it. She’d come to hate the root cellar. All winter she’d inventoried there, sitting in the dank with the fust and the mold nudging at the door. Cull the apples, unwrap the sweet potatoes, put the potatoes by, set the squash out for cooking before it was too late, all the while Brodis roaming the ridge to gather and salt the stock, or chasing game and checking rabbit boxes and taking the saddle horse into town for shoes. But she was the keeper of the house and the yard and the fields. She’d cooked and put up all manner of food. In the root cellar, in the weak air, the lamp guttered and the flame bowed and whickered. Only the bluest center stayed constant, low between the lamp’s brass thumbs, and on days when she overspent her time there, she found herself staring into its gentian eye.

She was tired of being inside.

The walks were the only part of her life that belonged to her alone, when she wasn’t obliged to chores nor mothering nor livestock. Matthew was old enough to take care of himself, and the black of night had become a time of possibility. If she didn’t spend it sleeping, well sir, that was hers to say.

Or maybe it was curiosity, a dare to herself to see could she get away with it.

And what would it mean if she did?

Now she stepped from the overhang of the porch into the paleness of the yard, where the full moon shrank into the branches of the blue-gray beech, its hair tattered with last year’s leaves. The outlines of its arms reached full across the chicken pen and into the yard to touch her broganned feet.

I’m here.

Behind her, the house squeezed itself shut like a fist.

Her feet found the path uphill without trying. Frost crystals grew up like mushrooms, and frozen puddles crunched beneath her feet, loud on account of the metal landscape. It was the same ice and water that had carved the mountains, the ancient seep and trickle of it under and into rock, its freezing and unfreezing, the cracking of granite, the insistent chiseling, water that found out the crevices and always moved downhill.

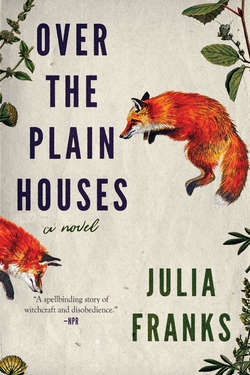

As soon as she cleared the level of the house she felt her lungs expand and relax and expand again. There in the blued clearing before her was the bowed outline of a fox, his back curled against the whitened earth, his nose intent and pointed at something in front of him.

I see you.

The animal arched up, hopped forward, and slapped his front paws against the frost-tight ground. Then he gave a vigorous shake of his head and was gone.

It’d been two years since she’d found the skeleton of that other fox, the bones bleached clean and so beautiful and sorrowful that she couldn’t bear to leave them. But when she’d brought them home for Matthew to reassemble on the porch, Brodis had stood apart and watched the two of them puzzling out the pieces, and not more than a minute had passed when he’d asked about the stew, and was supper on its way or not. And she’d heaved herself up from the floorboards and said it was true that she’d left off starting the cornbread too long.

The fox had been the first thing she’d taken for herself. But the way Brodis looked at it made it silly. That night she’d woke wide-eyed in the dark. It’d been easy to creep from the bed and pack up the fox and take it up the mountain. It’d been instinct that had taken her to the crevice in the side of the rock, the same overhang she and her cousins had played in as children. Except that this time she was alone, and grown, and it was dark. And there was no one looking to find her. There she’d set the lantern, and there she’d unwrapped the bones and puzzled them out, the skull an empty box, the ribcage a shell, the backbones precise and stacked like threaded bobbins. In the months that followed she’d brought other things too: river stones, and snail fossils, Matthew’s first teeth rattling around the bottom of a jelly jar, a Cherokee pot, programs from school plays and camp revivals, locks of hair and baby clothes, and whatever was unlikely and surprising that she could call her own. Other women she knew hosted weddings and infares or designed quilts and baskets and flowerbeds. Other women she knew planned. She didn’t. In place of planning, she preserved, with mason jars and jelly jars and the battery casing that kept her daughter’s baby blanket from the moths. And she held those glass moments close. That way you knew that whatever happened, you could always go back to that Christmas play program spread on your lap, that moment whenever they’d just darkened the theater and the audience had hushed of a sudden single accord, and your son stepped onto the stage. Whatever happened, you would always have that. You pulled those moments from the garbage and they were yours to own. They were proof you had lived. And they were enough, mostly.

Leastways for her. Where her son stashed his moments she hadn’t figured out.

On the mountain she knew her way without trying. There in front of her was the silhouette of the grandfather oak, its giant arms cradling the sky, there the rhododendron branch blocking the path, there the granite outcroppings where she’d hid as a child, there the grayback boulder spattered with lichen and festooned with laurel. She and Matthew had found arrowheads in its overhang. Now a movement caught her eye—the fox ribboning against the base of the boulder. Then he was gone. She stopped and smelled. Underneath the clean smell of ice was something hot and alive: the musky-coffee smell of pups, curled under the boulder maybe, blind in the dark, a secret sealed from the world.

She stored this information among her private collectings. Sometimes she kept these for herself, and sometimes, like the arrowheads, she gave them to Matthew as gifts.

Around her the pillars of the tulip trees vaulted up the sky, the moon throwing their columned shadows before them. The new-built classrooms seemed close, the dining hall and the dormitories all electrified, the books issued to each student for him alone.

There are scholarships. The lady agent had said it. She had a way of opening her eyes up wide when she meant to make a point.

It was certain Brodis wouldn’t like the idea coming from the outside. Not after the trains and the tobacco and the teams of city boys in shirtsleeves building national parks and kicking people out of their homes and damming up rivers. Not after the big game hunter who moved to Tennessee and imported magic Russian boar with tusks like elephants that could gore a man to death. Or the Baptist missionaries that poured in from Atlanta because the church in that city was affiliated and turns out there wasn’t any call for a mountain church to call itself Baptist unless they were affiliated too, and a whole group of them telling Brodis and Haver Brooks they couldn’t just call their church whatever they wanted unless they got it in with the national organization, and the national organization had its own preachers thank you very much, and when Haver and Brodis ignored them, here they came knocking on doors, their hands stacked with pamphlets.

And now this. It would need finagling. You had to take care for the timing. Tomorrow before bedtime might make.

On the ridge the hemlock crowded out the tulip trees. Old chestnuts twisted like the red carcasses of tortured ancient kings, their massive spiraled torsos lifeless and naked, their ghosts sifting among the castled evergreens. They had their secrets they weren’t telling either, and they remembered the ones that had left, the peregrines and the otters and the wolves and the beaver. And then the woods turned laurely, and the tree line dropped away, and the top of the mountain opened like a fairytale ballroom big as the horizon.

Across the clearing a pair of slanted yellow eyes stared at her, and even in that first moment she marked that they were narrow-set, intelligent eyes, bigger than a bobcat’s or a dog’s. But not a bear’s either. Then another pair and another. Rustling followed, but not the kind that signaled a charge. More like she’d invaded a jealous private party, and the participants now made ready to hide their illicit activities. She couldn’t see them, but she sensed that they studied her. There was a snort, and a single big-chested outline commenced to show itself: a wedge-shaped head with an absurd snout, small pointed ears and great tusks that curved toward the moon, tusks that spoke of jungles and exotic forests, of Mowgli and fairy-tale dragons that burned your house to the ground in a single breath. Behind the beast’s head bristled a silver-tipped collar, as if it was wearing a cape. Below that, its body and hindquarters dwindled to an absurd smallness.

It couldn’t be a pig. The legs were too long, the ears too pointed, the hooves too small. And yet there wasn’t any other thing in the world it could be.

It was them.

The beasts began a great shuffling, and within a second, the caped one turned and followed the crowd toward the west and the Tennessee ridge.

Irenie hadn’t known pigs could move that fast.

The bald was quiet then, but changed. Rooted-up turf lined the earth around her, and the air breathed sharp. Her foot landed in something soft. She lit the lantern to find a segmented mound of scat. It was still warm. But it didn’t smell like the shit of the hogs they put up before slaughter to harden the fat. It smelled like sulfur and decomposing flesh.

How had they come to be here?

The look of the yellow eyes in the night, the intention of them, meant something. They had judged her and found her meaningless, as if they’d been the ones to discover her instead of the other way round, as if whatever change they brought was already here, already bigger than her or Brodis.

She wrapped the pig dropping in a leaf and carried it that way between her thumb and finger. For now. Later she’d find a jar and store it in the cave with her other moments, the ones she’d saved for good. She didn’t tell Brodis about the pigs. It was only a matter of time before he’d know. Besides, it was her story to own, not his.