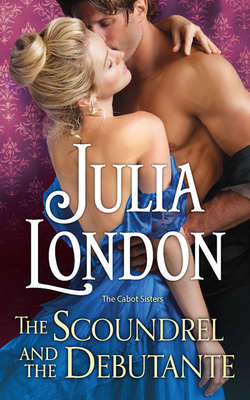

Читать книгу The Scoundrel and the Debutante - Julia London, Julia London - Страница 7

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

Blackwood Hall, 1816

IT WAS AN unspoken truth that when a woman reached her twenty-second year without a single gentleman even pondering the possibility of marriage to her, she was destined for spinsterhood. Spinsterhood, in turn, essentially sentenced her to the tedium of acting as companion to doddering dowagers as they dawdled about the countryside.

A woman without prospects in her twenty-second year was viewed suspiciously by the haut ton. There must be something quite off about her. It was impossible to think otherwise, for why would a woman, properly presented at court and to society, with means of dowry, with acceptably acknowledged connections, have failed to attract a suitor? There were only three possible explanations.

She was unforgivably plain.

She was horribly diseased.

Or, her older sisters’ scandalous antics four years past had ruined her. Utterly, completely, ruined her.

The third hypothesis was presented by Miss Prudence Cabot days after her twenty-second birthday. Her hypothesis was roundly rejected by her scandalous older sisters, Mrs. Honor Easton and Grace, Lady Merryton. In fact, when her older sisters were not rolling their eyes or refusing to engage at all, they argued quite vociferously against her theory, their duet of voices rising up so sharply that Mercy, the youngest of the four Cabot sisters, whistled at them as if they were the rowdy puppies that fought over Lord Merryton’s boot.

Her sisters’ protests to the contrary notwithstanding, Prudence was convinced she was right. Since her stepfather had died four years ago, her sisters had engaged in wretched behavior. Honor had publicly proposed marriage to a known rake and bastard son of a duke in a gaming hell. While Prudence adored George, it did not alter the scandal that had followed or the taint it had put on the Cabots.

Not to be outdone, Grace had endeavored to entrap a rich man into marriage in order to save them all from ruin, and somehow managed to trap the wrong man. It was the talk in London for months, and while Grace’s husband, Lord Merryton, was not as aloof as Prudence had always heard, his entry into the family had not improved Prudence’s prospects in the least.

Nor did it help in any way that her younger sister, Mercy, had a countenance so feisty and irreverent that serious thought had been given to packing her off to a young ladies’ school to tame the beast in her.

That left Prudence in the middle, sandwiched tightly between scandals and improper behavior. She was squarely in the tedious, underappreciated, put-upon, practically invisible middle where she’d lived all her life.

This, Prudence told herself, was what good manners had gotten her. She had endeavored to be the practical one in an impractical gaggle of sisters. The responsible one who had taken her music lessons just as faithfully as she’d taken care of her mother and stepfather while her sisters cavorted through society. She’d done all the things debutantes were to do, she’d caused not a whit of trouble, and her thanks for that was now to be considered the unweddable one!

Well, Mercy likely was unweddable, too, but Mercy didn’t seem to care very much.

“Unweddable is not even a proper word,” Mercy pointed out, adjusting her spectacles so that she might peer critically at Prudence.

“It’s also utter nonsense,” Grace said tetchily. “Why on earth would you say such a thing, Pru? Are you truly so unhappy here at Blackwood Hall? Did you not enjoy the festival we hosted for the tenants?”

A festival! As if her wretched state of being could be appeased with a festival! Prudence responded with a dramatic bang of the keys of the pianoforte that caused the three-legged dog Grace had rescued to jump with fright and topple onto his side. Prudence launched into a piece that she played very loudly and very skillfully, so that everything Grace or Mercy said was drowned out by the music.

There was nothing any of them could say to change her opinion.

Later that week, Prudence’s oldest sister, Honor, had come down from London to Blackwood Hall with her three children in tow as well as her dapper husband, George. When Honor heard of the contretemps between sisters, she’d tried to convince Prudence that a lack of a viable offer of marriage did not mean all was lost. Honor had insisted, with vigor and enthusiasm, that her sisters’ behavior had no influence on Prudence’s lack of an offer. Honor now reminded her that Mercy, against all odds, had been accepted into the prestigious Lisson Grove School of Art to study the masters.

“Well, naturally I was. I am quite talented,” Mercy unabashedly observed.

“Lord Merryton had to pay a pretty sum to sway them, didn’t he?” Prudence sniffed.

“Yes,” Grace agreed. “But if she were as plagued with scandal as you suggest, they would have refused her yet.”

“Refused Merryton’s purse?” Prudence laughed. “It’s not as if they had to marry her, for God’s sake.”

“I beg your pardon! What of my talent?” Mercy demanded.

“Hush,” Grace and Prudence said in unison. That spurred Mercy to push her spectacles up her nose and march from the room in her paint-stained smock.

Grace and Honor paid her no mind.

The debate continued on for days, much to Prudence’s dismay. “You must trust that an offer will come, dearest, and then you will be astonished that you put so much stock into such impossible feelings,” Honor said a bit condescendingly as the sisters dined at breakfast one morning.

“Honor?” Prudence said politely. “I kindly request—no, pardon—I implore you to cease talking.”

Honor gasped. And then she stood abruptly and flounced past Prudence with such haste that her hand connected a little roughly with Prudence’s shoulder.

“Ouch,” Prudence said.

“Honor means only to help, Pru,” Grace chastised her. “Honor means only to help.”

“I mean more than that,” Honor said sternly, charging back around again, as she really was not the sort to flee in tears when there was a good fight to be had. “I insist that you snap out of your doldrums, Pru! It’s unbecoming and bothersome!”

“I’m not in doldrums,” Prudence said.

“You are! You’re forever cross,” said Mercy.

“And moody,” Grace hastened to agree.

“I will tell you only what a loving sister will tell you truly, darling.” Honor leaned over the dining table so that she was eye level with Prudence. “You’re a bloody chore.” But she smiled when she said it and quickly straightened. “Mrs. Bulworth has written and asked you to come and see her new baby. Do go and see her. She will be beside herself with joy, and I think that the country air will do you good.”

Prudence snorted at that ridiculous notion. “How can I possibly be improved by country air when I am already in the country?”

“Northern country air is vastly different,” Honor amended. Grace and Mercy nodded adamantly that Honor was right.

Prudence would like nothing better than to explain to them all that calling on their friend Cassandra Bulworth, who had just been delivered of her first child, was the last thing she wanted to do. To see her friend so deliriously happy made Prudence feel that much more wretched about her own circumstance. “Send Mercy!”

“Me?” Mercy cried. “I couldn’t possibly! I’ve very little time to prepare for school. I must complete my still life painting, you know. Every student must have a complete portfolio and I haven’t finished my still life.”

“What about Mamma?” Prudence demanded, ignoring Mercy. They could not deny their mother’s madness necessitated constant supervision from them.

“We have her maid Hannah, and Mrs. Pettigrew from the village,” Grace said. “And we have Mercy, as well.”

“Me!” Mercy cried. “I just said—”

“Yes, yes, we are all intimately acquainted with all you must do for school, Mercy. On my word, one would think you were the only person to have ever been accepted into a school. But you aren’t leaving us for another month, so why should you not have the least responsibility?” Grace asked. Then she turned to Prudence and smiled sweetly. “Pru, we’re only thinking of you. You see that, don’t you?”

“I don’t believe you,” Prudence said. “But it so happens that I find you all quite tedious.”

Honor gasped with delight and clasped her hands to her breast. “Does that mean you’ll go?”

“Perhaps I shall,” Prudence sniffed. “I’ll be as mad as Mamma if I stay any longer at Blackwood Hall.”

“Oh, that’s wonderful news,” Grace said happily.

“Well, you needn’t rejoice in it,” Prudence said missishly.

“But we’re so happy!” Honor squealed. “I mean, happy for you,” she quickly corrected, and hurried around the table to hug Prudence tightly to her. “I think your mien will be vastly improved if you just step out into the world, dearest.”

Prudence scarcely thought so. Out into the world was where she lost all heart. Happy people, happy friends, all of them embarking on a life that Prudence had always hoped would be hers, made her terribly unhappy. Prudence was filled with envy, and she could not beat it down, no matter how much she would have liked, no matter how much she had tried. Even mortifyingly worse, Prudence’s envy of the happiness surrounding her was apparent. Lately, it felt as if even sunshine was a cruel reminder of her situation.

But as Mercy launched into her complaints that so much attention was being paid to Prudence when she needed it, Prudence decided she would go. Anything to be free of the happy chatter she was forced to endure day in and day out.

* * *

GRACE ARRANGED IT ALL, announcing grandly one afternoon that Prudence would accompany Dr. Linford and his wife north, as they would be traveling that way to visit Mr. Linford’s mother. The Linfords would deposit Prudence in the village of Himple where Mr. Bulworth would send his man to come and fetch her and bring her to their newly completed mansion. Cassandra, who had come out with Prudence and had received several offers of marriage in her debut Season compared to Prudence’s astounding lack of them, would be waiting with her baby.

“But the Linford coach is quite small,” Mercy said, frowning so that it caused her spectacles to slide down her nose. She was seated at her new easel, drawing a bowl of fruit for her painting. That’s what the masters did, she’d informed them earlier. They sketched first, then painted. “Prudence will be forced to carry on a conversation for hours,” she added absently as she studied her sketch.

“What’s wrong with conversation?” Honor demanded as she braided the hair of her daughter, Edith.

“Nothing at all if you care so much for the weather. Dr. Linford speaks of nothing else. It’s a fine day, and what not. Pru doesn’t care so much for weather, do you, Pru?”

Prudence shrugged. She didn’t care much for anything.

On the day of her departure, Prudence’s trunk and valise were carried downstairs to a waiting carriage that would ferry her to Ashton Down, where Prudence was to meet the Linfords at one o’clock. In her valise, she included her necessities—some ribbons for her hair, a silk chemise Honor had brought for her from the new London modiste she raved about, some lovely slippers, and a change of clothing. She said goodbye to her overly cheerful sisters and started off at a quarter to twelve.

The ever-efficient Blackwood Hall coach reached Ashton Down at ten past twelve.

“You needn’t wait with me, James,” Prudence said, already weary. “The Linfords will be along shortly.”

James, the driver, seemed uncertain. “Lord Merryton does not like the ladies to wait unattended, miss.”

For some reason, that rankled Prudence. “You may tell him that I insisted,” she said. “If you will deposit my things just there,” she said, waving absently at the sidewalk along High Street. She smiled at James, adjusted her bonnet, and took herself up the street to the dry goods and sundries shop, where she purchased some sweetmeats for the journey. When she made her purchase, she walked outside. She saw her things on the sidewalk as she’d asked, and the Blackwood Hall carriage was gone. Finally.

Prudence lifted her face to the late-summer sun. It was a warm, glorious day, and she decided to wait on the village green just across from her luggage. She arranged herself on a bench, folded her gloved hands over her package of sweetmeats and idly examined some flowers in a planter beside her. The blooms were fading...just like her.

Prudence sighed loudly.

The sound of an approaching coach brought her to her feet. She stood up, dusted off her lap, tucked her package in the crook of her arm and looked up the road, expecting to see the Linford coach roll down the street.

But it wasn’t the Linford coach—it was one of two private stagecoaches that came through Ashton Down every day, one midday, one later in the afternoon.

Prudence sat down heavily on the bench once more.

The coach pulled to a halt on the road before her. Two men jumped off the back runner; one of them opened the door. A young couple stepped out, the woman carrying an infant. Behind them emerged a man so broad in the shoulder he had to turn to fit through the opening. He fairly leaped out of the coach, landing sure-footedly, and adjusted the hat on his head. He looked as if he’d just returned from an architectural dig, dressed in buckskins, a lawn shirt and a dark coat that reached his knees. His hat looked as if it was quality, although it showed signs of wear. And his boots looked as if they’d not been shined in an age. He had a dusty shadow of a beard on his square jaw.

The man turned a slow circle in the middle of the street, oblivious to the young men who rushed to change the horses and deposit luggage onto the curb. Whatever the passenger saw caused him to suddenly stride to the front of the coach and begin to argue vociferously with the driver.

Prudence blinked with surprise. How interesting. She straightened her back and looked around, wondering what the gentleman had seen to anger him so. But observing nothing out of the ordinary on the village green or on the high street, she stood up, and as casually and inconspicuously as she might, she moved closer, pretending to examine some rose blooms so that she might hear his complaint.

“As I said, sir, Wesleigh is just up the road there. A half-hour walk, no more.”

“But you don’t seem to understand my point, my good man,” the gentleman said in an accent that was quite flat. “Wesleigh is a house. Not a settlement. I understood I’d be delivered to an estate. An estate! A very large house with outbuildings and various people roaming about to do God knows what it is you do in England,” he exclaimed, his hands busily sketching the estate in the air.

The driver shrugged. “I drive where I’m paid to drive, and I ain’t paid to drive to Wesleigh. Ain’t a grand house there by no means.”

“This is preposterous!” the man bellowed. “I’ve paid good money to be delivered to the proper place!”

The driver ignored him.

The gentleman swept his hat off a head full of thick brown hair and threw it with great force to the ground. It scudded along and landed very close to Prudence. He looked about for his hat and, spotting Prudence at the edge of the green, he suddenly strode forward, the paper held out before him.

Prudence panicked. She looked about for a place to escape, but he guessed her intention. “No, no, stay right there, I beg you,” he said sternly. “I must have someone speak to that man and explain to him that I am to be delivered to Wesleigh!”

“Wesleigh?” Prudence asked. “Or Weslay?”

That drew the man up, midstride. He stared at her with eyes the rich color of golden topaz, which slowly began to narrow on her, as if he thought she meant to trick him. He hesitantly moved forward, the paper still held out before him. “If you would be so kind?” he asked through clenched teeth, practically shoving the paper at her.

Prudence took it between forefinger and thumb and gingerly extracted it from his grip. Someone had written—scrawled, really, in long bold strokes—“West Lee, Penfors.”

“Hmm,” she said, squinting at the scrawl. “I suppose you mean Viscount Penfors.” She peeked up at the stranger, who was staring darkly at her. She could feel the potency of his gaze trickling into her veins. “Lord Penfors resides at Howston Hall, just outside of Weslay.”

“Yes, exactly as I wrote,” he said, pointing to the paper.

“But this says ‘West Lee.’”

“Just as you said.”

“No, sir, I said ‘Weslay.’ I’ve never heard of West Lee,” she said, trying to enunciate the subtle difference in the sound of the names. “And unfortunately, it appears you’ve mistakenly arrived in Wesleigh.”

The stranger’s face darkened, and Prudence had an image of him exploding, little bits of him raining down on the street. “I beg your pardon, miss, but you are not making any sense,” he said tightly. He reached for the edge of the paper with his forefinger and thumb as she’d done and yanked it free. “You have said West Lee three times now, and I don’t know if you mean to tease me or if there is something else at work here.”

“I am not teasing you,” she objected, horrified by the suggestion.

“Then it must be something else!”

“Something else?” What could he possibly mean? Prudence couldn’t help but smile. “I assure you, I am not privy to any scheme or conspiracy to keep you from Weslay, sir.”

His frown deepened. “I am happy to amuse you, miss. But if you would kindly point me in the direction of at least one of these West Lees, and preferably the one where I may find this Penfors fellow, I would be most grateful.”

“Oh.” She winced lightly.

“Oh?” he repeated, leaning forward. “What does ‘oh’ mean? Why are you looking at me as if you’ve lost my dog?”

“You’ve gone the wrong direction.”

“So I gathered,” he drawled.

“Wesleigh is just down the road here, a small village with perhaps five cottages. Weslay is north.” She pointed in the direction the stage had just come.

He looked in the direction she pointed. His face began to mottle. “How far?” he managed, his voice dangerously low.

“I can’t be entirely certain, but I’d say...two days?”

The gentleman stranger clenched his jaw. He was big and powerful, and Prudence imagined his fury shaking the ground beneath his feet. “But that is indeed where you will find this Penfors fellow,” she hastened to add, and once again tried not to smile. It was absurd to refer to a viscount as a fellow!

“North?” he bellowed, throwing his arms wide.

Prudence took one cautious step backward and nodded.

The man put his hands on his waist, staring at her. And then he turned slowly from her. She thought he meant to walk away, but he kept turning, until he’d gone full circle, and when he faced her again, his jaw was clenched even more tightly. “If I may,” he asked, his voice strained, “have you a suggestion for how I might reach this West Lee that is two days away?”

“It’s not West—” She shook her head. “You might take the northbound stagecoach. It comes through Ashton Down twice a day. The first one should be along at any moment.”

“I see,” he said, but it was quite apparent he didn’t see at all.

“You might also buy passage on the Royal Post coach, but it’s a bit more costly than the passenger stages. And it comes through only once a day.”

He eyed her distrustfully. “Two days either way?”

She nodded. She smiled sympathetically. She would not like to be sausaged into a stagecoach for two days. “I fear it is so.”

He shoved his fingers roughly through his dark brown hair and muttered something under his breath that she couldn’t quite make out but sounded as if she ought not to hear.

“Where might I purchase passage?” he asked briskly.

She looked around him—that is, she leaned to her right to see around his broad chest—to the stagecoach inn. “I’ll show you if you like.”

“That,” he said firmly, “would be most helpful.” He bent down, scooped up his hat, dusted it off by knocking it against his knee, then put it back on his head. His gaze traversed the length of her before he stepped back and swept his arm before him, indicating she should lead him.

Prudence walked across the street, pausing as the gentleman instructed the coachman to leave his trunk and bag on the sidewalk with the other luggage pieces to be loaded on the northbound coach. He stared wistfully at the coach as it pulled away, headed south, before turning back to Prudence and following her into the inn’s courtyard. She walked through a pair of doors that went past the public room and into a small office. It was close, and she had to dip her head to step inside. The ceiling was uncomfortably low, and the smell of horse manure permeated the air, as the office was situated between the stables and the public rooms.

The gentleman passenger was well over six feet and had to stoop to enter. Once inside, his head brushed the rafters. He batted at a cobweb and grunted his displeasure.

“Aye, sir?” said a clerk, appearing behind the low counter.

The gentleman stepped forward. “I should like to buy passage to West Lee,” he said.

“Weslay,” Prudence murmured.

The gentleman sighed loudly. “What she said.”

“Three quid,” the clerk said.

The gentleman removed his purse from his pocket and opened it. He fussed through the coins there, examining each one as he withdrew them. Prudence stepped forward, leaned around him, and pointed at three of the coins.

“Ah,” he said, and handed them to the clerk, who in turn handed the gentleman a ticket.

“The driver requires a crown, and the guard a half,” the clerk said.

“What?” the gentleman said. “But I just gave you three pounds.”

The clerk tucked the coins into a pocket on his apron. “That’s for the passage. The driver and the guard, they get their pay from the passengers.”

“Seems like a dodge.”

The clerk shrugged. “If you want passage to Weslay—”

“All right, all right,” the gentleman said. He peered at his ticket and sighed again. He gestured for Prudence to go out ahead of him, then fit himself through the door into the inn’s main hall and followed her into the courtyard.

They paused there. He smiled for the first time since Prudence had seen him, and she felt a little twinkle of desire when he did. He looked remarkably less perturbed, and in all honestly, he looked astoundingly pleasing to the eye when he smiled. It was a rugged, well-earned smiled. There was nothing thin about it. It was an honest, glowing sort of smile—

“I am grateful for your assistance, Miss...?”

“Cabot,” she said. “Miss Prudence Cabot.”

“Miss Cabot,” he said, and bowed his head slightly. “Mr. Roan Matheson,” he added, and stuck his hand out.

Prudence glanced uncertainly at his hand.

So did he. “What is it? Is my glove soiled? So it is. I beg your pardon, but I’ve come a very long way without benefit of anyone to do the washing.”

“No, it’s not that,” she said with a shake of her head, although her thoughts were spinning with the how and why and from where he’d come such a long way.

“Oh. I see.” He removed his glove and extended his hand once more. She noticed how big it was, how strong. How long and thick his fingers were and the slight nicks on his knuckles. A hand that was not afraid of work. “My hand is clean,” he said impatiently.

“Pardon? Oh! No, it’s just that it’s rather unusual.”

“My hand?” he asked curiously, holding it up to have a look.

“No, no.” She was being rude. She looked up at his startling topaz eyes. And at his hair, too, dark brown with streaks of lighter brown, and longer than the current fashion, which he had carelessly brushed back behind his ears. It was charmingly foreign. He was charmingly foreign and...virile. Yes, that was it. He looked as if he could move mountains about for his amusement if he liked. Her pulse, Prudence realized, was doing a tiny bit of fluttering. “It’s unusual that you are offering your hand to be—” she paused uncertainly “—shaken?”

“Of course I offered it to be shaken,” he said, as if it were ridiculous she would ask. “Why else would one offer a hand, Miss Cabot? To shake. To acknowledge a kindness or a greeting—”

She abruptly put her hand in his, noting how small it seemed in his palm.

He cocked his head. “Are you afraid of me?”

“What? No!” she said, flustered. Maybe she was a tiny bit afraid of him. Or rather, the little shocks of light that seemed to flash through her when he looked at her like that. She curled her fingers around his. He curled tighter. “Oh,” she said.

“Too firm?” he asked.

“No, not at all,” she said quickly. She liked the feel of his grip on her hand and had the fleeting thought of his grip somewhere else on her altogether. “I beg your pardon, but I am unaccustomed to this. Here, men offer their hands to other men. Not to ladies.”

“Oh.” He hesitantly withdrew his hand. But he looked at her with confusion. “Then...what am I to do when I meet a woman?”

“You bow,” she said, demonstrating for him. “And a lady curtsies.” She curtsied, as well.

He groaned as he pulled his glove back on. “May I be brutally honest, Miss Cabot?”

“Please,” she said.

“I have come to England from America on a matter of some urgency—I must fetch my sister who is enjoying the fine hospitality and see her home. But I find this country confounding. I sincerely—” He suddenly turned his head, distracted by the sound of a coach rumbling into town. It was the northbound stage, and it pulled to a halt on the street just outside the courtyard. Two men sitting atop the coach jumped down; two young men climbed down from the outboard. Another man was waiting on the sidewalk to catch the bags that one of the coachmen began to toss to him.

The coach looked rather full, and Prudence felt a moment of pity for Mr. Matheson. She couldn’t possibly imagine how he would maneuver his large body into that crowded interior.

“Well, then, there we are,” he said, and began to stride toward the coach. He paused after a few steps and glanced over his shoulder at Prudence. “Aren’t you coming?”

Prudence was momentarily startled. She suddenly realized he believed she was waiting for the coach, too. She opened her mouth to correct him, to inform him she’d be traveling by private coach, but before the words could fall from her tongue, something warm and shivery sluiced through her. Something silky and dark and dangerous and exciting and compelling...so very compelling.

She wouldn’t.

But why wouldn’t she? She thought of riding in a coach with the Linfords, and the talk of weather. She thought of riding on a stagecoach—something she had never done—and riding with Mr. Matheson. There was something about that idea that thrilled her in a way nothing had in a very long time. He was so masculine, and her pulse fluttered at the idea of passing a few hours with him. “Ah...” She glanced back at the inn, debating. She’d be mad to do such a thing, to put herself on that stagecoach with him! But wasn’t this far more interesting than traveling with the Linfords? She had money, she had her things. She knew how to reach Cassandra Bulworth. What was stopping her? Propriety, for heaven’s sake? The same propriety that had been her constant companion all these years and had doomed her to spinsterhood?

She glanced again at Mr. Matheson. Oh yes, he was very appealing in a wild, American sort of way. She’d never met an actual American, either, but she imagined them all precisely like this, always rebelling, strong enough to forge ahead without regard for society’s rules. This man was so different, so fresh, so incurably handsome and so blessedly lost! She might even convince herself she was doing him a proper kindness by seeing him on his way.

Mr. Matheson misunderstood her look, however, because he flushed a bit and said, “I beg your pardon. I didn’t mean to rush you.”

Prudence smiled broadly—he thought she wanted the privy.

Her smile seemed to fluster him more. He cleared his throat and looked to the coach. “I’ll...I’ll see you on the coach.”

“Yes,” she said, with far more confidence than she had a right to. “Yes, you will!”

He looked at her strangely, but then gave her a curt nod and began striding for the coach, pausing to dip down and pick up one of the bags with one hand, then toss it up to a boy who was lashing the luggage on the boot.

There was no time to debate it; Prudence whirled about and hurried back to the office, her heart pounding with excitement and fear. A little bell tingled as she walked in.

The clerk turned round and squinted at her. “Miss?”

“A ticket to Himple, please,” she said, and opened her reticule.

“To Himple?” he repeated dubiously, and peered curiously at her.

“Please. And if you have some paper? I must dash off a note.”

“Two quid,” he said, and rummaged around until he found a bit of vellum she might use.

He handed her a pencil, and Prudence dashed off a hasty note to Dr. Linford that she would ask the coach boys to deliver to him. She jotted down the usual salutations, her wishes that the Linfords were well and his mother on the mend. And then she wrote an explanation for her change of plans.

I beg your pardon for any inconvenience, but as it happens, I have taken a seat in a friend’s coach. She is likewise bound for Himple and it was no trouble for her to include me in her party. Do please forgive the short notice, but the opportunity has only just come about. Thank you kindly for your offer to see me safely to my friends’, but I assure you I am in good hands.

She shivered at the sudden image of the gentleman’s hands.

My best wishes for your journey and your mother’s health. P.C.

She folded the note, smiled at the scowling clerk, and picked up her ticket. “Thank you,” she said, and fairly skipped out of the office.

Her heart was racing—she couldn’t believe she was doing something so daring and bold! So fraught with risk! So very unlike her! But for the first time in months, perhaps even years, Prudence felt as if something astonishing was about to happen to her. Good or bad, it didn’t matter—the only thing that mattered was that something different this way came, and she was giddy with excitement.