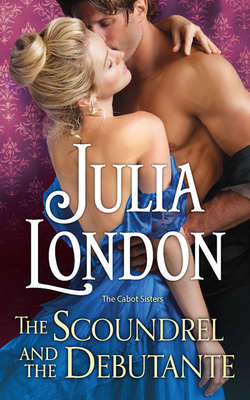

Читать книгу The Scoundrel and the Debutante - Julia London, Julia London - Страница 9

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

PRUDENCE’S CHIN BOUNCED off something very hard, and her hand sank into something soft. Her first groggy thought was that it was a lumpy pillow. But when her eyes flew open, she saw that her chin had connected with Mr. Matheson’s shoulder...and her hand with his lap.

He stared wryly at her as awareness dawned on her. She gasped; he very deliberately reached up to remove the tip of her bonnet’s feather that was poking him in the eye.

Prudence could feel the heat flood her cheeks and quickly sat up. She straightened her bonnet, which had somehow been pushed to one side. “What has happened?” she exclaimed, shuffling out from the wedge between Mrs. Scales and Mr. Matheson to the edge of the bench, desperate that no part of her was touching any part of that very virile man. But her hip was still pressed so tightly against his thigh that she could feel the slightest shift of muscle beneath his buckskins.

It was alarmingly provocative. Prudence didn’t move an inch for several seconds, allowing that feeling to imprint itself in her skin.

“I assume we’ve broken a wheel,” Mr. Matheson said. The coach dipped to the right and swayed unsteadily. The driver cursed again, loudly enough that the round cheeks of the two sisters turned florid.

Mr. Matheson reached for the door and launched himself from the interior like a phoenix, startling them all. Prudence leaned forward and looked through the open door. The coach was leaning precariously to that side. She looked back at her fellow travelers and had the thought that if the two ladies tried to exit the coach at the same time, it might topple over. She fairly leaped from the coach, too, landing awkwardly against a coachman who had just appeared to help them down.

“What has happened?” Prudence asked.

“The wheel has broken, miss.”

Mr. Matheson, she noticed, was among the men who had gathered around the offending wheel. He’d squatted to study it, and Prudence wondered if he was acquainted with wheels in general, or merely curious.

There ensued quite a lot of discussion among the men as Mr. Matheson dipped down and reached deep under the coach with one arm, bracing himself against the vehicle with his other hand. Was it natural to be a bit titillated by a man’s immodest address of a mechanical issue? Certainly she had never seen a gentleman involve himself in that way.

When Mr. Matheson rose again, he wiped his hand on his trousers, leaving a smear of axle grease. That did not repulse Prudence. She found it strangely alluring.

“The axle is fine,” he announced.

There was more discussion among the men, their voices louder this time. It seemed to Prudence that they were all disagreeing with each other. At last the driver instructed the women and the old gentleman away from the coach while the men attempted to repair the wheel. Mr. Matheson was included in the group that was shooed away.

The team was unhitched, and some of the men began to stack whatever they could find beneath the coach to keep it level when the wheel was removed.

“My valise!” Prudence cried, and darted into the men to retrieve it, pulling it away before it could be used as a prop.

Then Mrs. Tricklebank and Mrs. Scales made seats on some rocks beneath the boughs of a tree, taking the old man and the boy under their wings and fussing around them. There was no seat left for Prudence, so she sat on a trunk.

They watched the men prop the carriage up with rocks and luggage and some apparatus from the coach itself, then remove the wheel. Mr. Matheson had returned to the problem and was in the thick of it, lending his considerable strength to the work. Prudence wondered if he had some sort of occupation that required knowledge of wheels. She couldn’t see why else he might be involved. It wasn’t as if there weren’t enough men to do the work. The only other slightly plausible explanation was that he somehow enjoyed such things.

The elderly gentleman grunted a bit and moved around in an effort to find some comfort, forcing the sisters to the edges of the rocks.

“He may be an American and a bit crude, but one cannot argue that he cuts a fine figure of a man,” Mrs. Scales said wistfully.

Prudence blinked. She looked at Mrs. Scales and realized that both sisters were admiring Mr. Matheson’s figure.

“Mrs. Scales, how vulgar!” Mrs. Tricklebank protested. But she did not look away from Mr. Matheson’s strong back.

The ladies cocked their heads to one side and silently considered his muscular figure. Frankly, his size and bearing made the Englishmen around him look a bit underfed.

He’d removed his coat, and Prudence could see the ripple of his muscles across his back, the outline of his powerful legs and hips straining against his trousers as he dipped down. Prudence could feel a bit of sparkly warmth snaking up her spine and unbuttoned the top two buttons of her spencer. “It’s rather too warm this afternoon, isn’t it?” she asked no one in particular. No one in particular responded.

As they continued to privately admire Mr. Matheson, another heated discussion broke out among the men. This time, a coachman was dispatched under the coach, crawling in so far that only his boots were visible. The other men hovered about, making sure the coach stayed put on its temporary perch. The coachman at last wiggled out from beneath the coach and in a low voice delivered a piece of news that was apparently so calamitous that it caused the men to burst into even louder argument all over again.

The driver ended it all with a shout of “Enough!”

At that point, Mr. Matheson whirled away from the gathered men, his hands on his waist. He took a very deep breath.

“What do you suppose is his occupation?” Mrs. Scales mused, clearly unruffled by the shouting and arguing. “He seems so...strong.”

“Quite strong,” said Mrs. Tricklebank. “Perhaps a smithy?”

“His clothes are too fine for a blacksmith,” Prudence offered.

Mrs. Tricklebank produced a fan, and with a sharp flick of her wrist, she began to fan herself. “Yes, I think you’re right. I think he comes from means.”

Mr. Matheson suddenly whirled back to face the men and roughly loosened his neckcloth. He began to speak sternly, rolling up his sleeves as he did, revealing forearms as thick as fence posts. He reached for the wheel and picked it up.

The sisters gasped in unison with Prudence; such a display of brawn was unexpected and stirring. She very much would have liked to see what he meant to do with that wheel, but the driver, clearly unhappy with Mr. Matheson’s efforts, wrested the wheel from his grip. Mr. Matheson reluctantly let it go, grabbed up his coat and stalked away from the men as the driver carefully leaned the wheel against the coach.

He kept stalking, striding past the ladies, his expression dark.

“What has happened?” Mrs. Tricklebank cried.

“What has happened?” Mr. Matheson repeated sharply, and whirled around to face the ladies and the old man. “I’ll tell you what has happened. That fool driver,” he said, pointing in the direction of the men, “insists that we wait for another coach instead of repairing the wheel and being on our way.” He jerked his shirtsleeves down as he cast another glare over his shoulder for the driver. “One would think a man who drives a team and a coach for his living might carry a tool or two with him.” He shoved into his coat, then dragged his hand through his hair. He muttered something under his breath and turned away from the coach, taking several steps toward an overgrown meadow, and then standing with his back to them, his legs braced apart, his arms akimbo.

For a moment, Prudence thought he meant to stomp away. She could imagine him striding across the fields all the way to the seashore, his jaw clenched, boarding the first ship he found and sailing to America.

“Why should that make him so desperately unhappy?” Mrs. Scales asked loudly.

“Because the good Lord knows when another coach might happen along!” he shouted over his shoulder.

The women exchanged a look. They all knew that two stagecoaches traveled this route every day, as did the Royal Post. A conveyance of some sort would be along shortly. But no one dared say it to Mr. Matheson, as he seemed very perturbed as it was. He was so perturbed in fact, muttering something under his breath, that it struck Prudence as oddly amusing. Try as she might to keep the smile from her face, she could not.

Unfortunately, Mr. Matheson chose that moment to turn back to the group. His gaze landed on her and his brow creased into a frown at the sight of her smile. “What is it?” he demanded irritably. “Have I said something to amuse you?”

All heads swiveled toward Prudence, which only made her amusement more irrepressible. She had to dip her head, cover her mouth with her hand. Her shoulders were shaking with her effort to keep from laughing out loud.

“Splendid,” Mr. Matheson said, nodding as if he was neither surprised nor unsettled by her laugh.

“I beg your pardon,” Prudence said, and stood up, the smile still on her face. “I do sincerely beg your pardon. But you’re very...distraught.”

He looked her up and down as if she puzzled him, as if he couldn’t understand what she was saying. His study of her made Prudence suddenly aware of herself—of her arms and limbs, and her bosom, where his gaze seemed to linger a moment too long. “Of course I’m distraught,” he said, in a manner that had her curious if he merely disliked the word, or if he disliked that she was not equally distraught. “I have important business here and the delays I’ve already suffered could make this entire venture disastrous!”

Prudence paused. “Ah. The delay you brought on by going in the wrong direction, of course, and then this one on top of that.”

He glared at her.

“Oh. Pardon,” she said, and glanced at the others. “Was it a secret? But another coach will be along shortly,” she cheerfully added. “You may depend that there are at least two more coaches that travel this route each day.”

“That’s wonderful news, Miss Cabot,” he said, moving toward her. “And what are we to do while we wait? Nothing? Should we not try and solve our problem?” he asked, gesturing to the coach.

“Well, I certainly don’t intend to stand and wait,” Mrs. Scales announced grandly.

As no one seemed inclined to stand and wait, or solve their problem, the waiting commenced.

The men settled on the side of the road on upturned trunks, the ladies and the old man on their rocks. Mr. Matheson made several sounds of impatience as he wandered a tight little circle just beyond them. Occasionally, he would walk up to the road and squint in the direction they’d come, trying to see round the bend in the road and through the stand of oak trees that impeded the view of the road. And then he’d swirl back again, stalking past the men sitting around the broken wheel, and to the meadow, only to repeat his path a few moments later.

Mrs. Scales, Prudence realized, was studying her as Prudence studied Mr. Matheson. “Did you say there was no one who might have seen you safely to your friend, my dear?” she asked slyly.

The woman was impossible. But Prudence had grown up with three sisters—she was well versed in the tactics of busybodies and smiled sweetly. “I didn’t say that at all, Mrs. Scales. What do you think? Perhaps the time might pass more quickly if we think of something to do,” she suggested, hopping up from her seat.

“What might we possibly do?” Mrs. Scales scoffed.

“A contest,” Prudence said, her mind whirling.

“God help me,” Mr. Matheson muttered.

“Yes, a contest!” Prudence said, stubbornly standing behind her impetuous idea.

“Such as?” Mrs. Scales inquired. “We’ve no cards, no games.”

“I know! A footrace,” Mrs. Tricklebank suggested brightly, which earned her a look of bafflement from her sister and the old man.

“And who do you suggest engage in a footrace, Nina?”

“Perhaps something a bit less athletic,” Prudence intervened. “Something—”

“Marksmanship.”

This, the first word uttered by the elderly gentleman, was so surprising that they all paused a moment to look at him.

“I had in mind a word game or something a bit tamer, but very well,” Prudence said. “Marksmanship it is.”

“That’s absurd!” Mrs. Scales exclaimed. “Again, who shall participate?”

“Well, the gentlemen, certainly,” Prudence said. “I’ve yet to meet a proper gentleman who wasn’t eager for sport.”

“I’m not sure you want to put firearms in the hands of some of our fellow travelers,” Mr. Matheson said.

Prudence looked at the men lounging about. He had a point. But Mrs. Scales was watching her so intently that Prudence didn’t dare sit back down. “Then I’ll participate,” she said, turning about.

Her pronouncement was met with a lot of snorting.

But Mr. Matheson laughed...with great amusement. “That’s preposterous.”

Prudence’s mouth dropped open. “How can you say so?” she objected. “I’ve been taught to shoot!”

“Why ever for?” Mrs. Scales cried. “On my word, Mrs. Tricklebank, the state of society is exactly as I feared—ladies are not ladies at all!”

Now Prudence was doubly offended. “I beg your pardon, I was taught to shoot for sport, obviously!”

“I think there is nothing obvious about it,” Mrs. Scales said, and snapped open her fan and began to wave it in time with her sister’s.

“I like this idea,” Mr. Matheson said, nodding. He folded his arms and studied Prudence intently, a droll smile on his face that transformed him. His eyes were suddenly shining. “I like it very much, in fact. What do you say we limit the contest to just the two of us to begin,” he said, gesturing between them. “Anyone here may challenge the victor.”

Prudence looked back at the others. She expected some gentleman to stand up and express a desire to shoot. But no one did.

“Well, then, Miss Cabot?” Mr. Matheson said. “Wasn’t it your idea to pass the time?”

It was. And in hindsight, it appeared to be a very bad idea. It was very unlike her to speak so boldly and impetuously, and now Prudence knew why her sisters were accustomed to talking out of turn and saying outrageous things. How did they do it? How did they say impetuous things and then do impetuous things?

Mr. Matheson was watching her with far too much anticipation. As if he couldn’t wait to put a firearm in her hand. His smile had broadened. “Perhaps these good people might like to wager on our contest,” he said smoothly, gesturing grandly to the ladies.

“Wager,” said the old man, nodding.

“Ooh,” said Mrs. Scales. “I certainly have been known to enjoy a wager or two.” She tittered as she opened her reticule. Prudence gaped at the woman in surprise. Mrs. Scales glanced at her expectantly. “Well? As the gentleman said, it was your idea.”

“Yes, all right,” Prudence said crossly. What a fool she was! She had been taught to shoot. The earl, as they had always referred to her stepfather, had insisted his stepdaughters be properly instructed in riding, shooting, gaming and archery. He said that they should be prepared to meet their match in a man. Unfortunately, Prudence had not met her match in a man in such a long time that she was quite unpracticed at shooting now.

“We will need a target,” Matheson said with all the confidence of a man who knew he would win and win handily. That trait, Prudence discovered, was just as maddening whether a gentleman was British or American.

“I’ve one,” said the old man. He reached into his pocket and withdrew a flask. He tipped it up at his lips and drained what was left, then handed it to Mr. Matheson.

“A perfect target. Thank you, sir,” Matheson said. He was enjoying this now, winking slyly at Prudence as he passed her, carrying the flask.

That flask looked awfully small to Prudence. “I don’t have a firearm,” she quickly pointed out, hoping that would be the end of it.

“Then you may use mine,” Mr. Matheson said, and smiled as he reached deep into his coat and withdrew it. “I suggest you remove your gloves, Miss Cabot.”

The sisters fluttered and cooed at that, and then unabashedly admired Mr. Matheson as he strolled away to set the flask on another rock.

There was no escape. Prudence yanked her gloves from her hands, muttering under her breath about fools and angels.

Mr. Matheson walked back to where she stood and, with the heel of his boot, he scraped a line in the dirt. “Give me your hand,” he said.

“My hand?”

He impatiently took her hand, his palm warm and firm beneath hers. He pressed the gun into her palm and wrapped her fingers around the butt of it. He squeezed lightly and smiled down at her, his gold-brown eyes twinkling with what Prudence read as sheer delight. “Ladies first,” he said, and let go of her, stepping back.

Prudence looked down at the gun. It had a pearled handle and silver barrel, not unlike the pistol her stepbrother, Augustine, liked to show his friends. But Augustine kept his pistol in a case at Beckington House in London. He did not wear it on his person. Moreover, Mr. Matheson’s gun was smaller than the gun she’d been taught to fire.

“You know how to fire it, don’t you?” he asked as she studied the gun.

“Yes!” She lifted the gun to have a look. “That is, I assume that the trigger—”

“I suspected as much,” Mr. Matheson said. He stepped forward, took her by the wrist and swung her about so that her back was against his chest. “I would feel more comfortable,” he said, a bit breathlessly, “if you do not point it at me.”

“Oh, I beg your pardon.”

He leaned over her shoulder and extended her arm with the gun, helping her to sight the target. He showed her how to cock it. “Would you like a practice round?”

A practice round? No, she wanted this over as quickly as possible. “Not necessary,” she said pertly.

One corner of his mouth tipped up. Prudence had to force herself to look away from that mouth. Those lips, full and moist, made her a little unsteady and she needed all her wits about her.

“Let the contest begin,” Mr. Matheson said, and stepped back once more to take his place among the few gentlemen passengers who had wandered over to have a look.

As Prudence studied her target, there seemed to be a lot of chatter at her back as well as the sound of coins clinking when they were tossed into the hat the old man had taken off the young man’s head as people made their bets. There was laughter, too, and Prudence wondered if it was directed at her.

“Go on, Miss Cabot. We don’t want night to fall before you’ve had your chance,” Mr. Matheson said, and someone snickered.

Prudence glanced coolly at him over her shoulder. She lifted her arm. The pistol was heavy in her hand as she tried to sight the flask. Mr. Matheson had put it at what seemed like a great distance. Her arm began to quiver—she was mortified by that. She aimed as best she could, closed one eye...and then the other...and fired.

The sound of breaking glass startled her almost as much as the kick from the gun that sent her stumbling backward. She’d not expected to hit the target at all, much less head-on as she seemed to have done in a moment of sheer dumb luck. Prudence gasped with delight and relief and whirled about. “Did you see?” she demanded of all of them.

“Of course we saw!” Mrs. Scales said. “We’re sitting right here.”

Prudence squealed with jubilant triumph, as if she’d known all along she could do it. “Your turn, Mr. Matheson,” she said cheerfully as two men hurried by her to examine the flask. “But it appears we’ll need another target.” She curtsied low and held out the gun to him.

The slightest hint of a smile turned up the corner of his mouth. “It certainly does,” he said, and looked at her warily, as if he expected her of some sleight of hand. He took the gun Prudence very gingerly held out to him.

“I’ve a target!” Mrs. Scales called out. She held up a small handheld mirror.

“Ruth, Mr. Scales gave that to you!”

“Hush, now. He can give me another one, can’t he? Make your wager.”

A man took the mirror and walked across the meadow to prop it where the flask had been.

“Watch now, Miss Cabot, and I will demonstrate how to shoot a pistol,” he said. He stepped to the line he’d drawn in the dirt. He put one hand at his back, held the gun out and fired. He clearly hit something; the mirror toppled off the back of the rock. Two gentlemen moved forward to have a look; Prudence scampered to catch up with them and see for herself. One of them leaned over the rock, picked up the mirror and held it aloft. The mirror was, remarkably, intact for the most part, but a corner piece had either broken off or been shot off.

“I win!” Prudence cried with gleeful surprise. “You missed!”

“I most certainly did not miss,” Mr. Matheson said gruffly, gesturing to the broken mirror. “Do you not see that a piece is missing?”

“Must have grazed it,” one of the men offered. “You hit the rock, here, see? And the bullet—”

“Yes, yes, I see,” Mr. Matheson said, waving his hand over the rock. “Nevertheless, the object has been hit. We have a tie.”

“Then who is to receive the winnings?” Mrs. Scales complained as the sound of an approaching coach reached them.

Prudence didn’t hear the answer to that question—her heart skipped several beats when she saw the coach that appeared on the road. It was not the second stagecoach as they all expected—it was Dr. Linford. Prudence’s heart leaped with painful panic. One look at her and Dr. Linford would not only know that she’d lied, but he would also demand she come with him at once. He would tell her brother-in-law Lord Merryton, who would be quite undone by her lack of propriety. That was the one thing Merryton insisted upon, that their reputations and family honor be kept upmost in their minds at all times. As Merryton generously provided for Prudence and Mercy and her mother, and had indeed paid dearly to ensure that the patrons of the Lisson Grove School of Art overlooked Mercy’s family and placed her in that school, Prudence couldn’t even begin to fathom all the consequences of her being discovered like this. Moreover, she had no time to try—she looked wildly about for a place to hide as the Linford coach rolled to a halt. But the meadow was woefully bare, and there was nothing but Mr. Matheson’s large frame to shield her, so she darted behind him, grabbing onto his coat.

“What the devil?”

He tried to turn but she pushed against his shoulder. “Please,” she begged him. “Please, sir, not a word!”

“Are you hiding?” he asked incredulously.

“Yes, obviously!”

“Good God,” he muttered. His body tensed. “Miss Cabot,” he said softly, and she thought he’d say he would not help her, that she must step out from behind him. “Your feather is showing.”

“Please indulge me in this. I shall pay you—”

“Pay! Damn it, your feather is showing!”

The feather in her bonnet! Prudence gasped and quickly yanked the feather from her bonnet and dropped it. She stepped closer to his back, practically melding herself onto him. She could smell the scent of horseflesh, of leather and brawn, and she closed her eyes and pressed her cheek to the warmth of his back. The superfine felt soft against her skin, and she closed her eyes, feeling entirely safe in that sliver of a moment.

“What are you doing?” he demanded softly.

“Hiding,” she whispered. “I told you.”

“I understand you are hiding, but you’re touching me.”

“Yes, I am,” she said with exasperation. Was he unfamiliar with the concept of hiding? “I would crawl under your coat if I could. That’s what hiding is.”

“Good afternoon!” she heard Dr. Linford call out to all. “May we help?”

Prudence was doomed. She would be humiliated before Mr. Matheson and exposed to scandal—all of which seemed far worse than Mr. Matheson’s displeasure that she was touching him.

“Turn about,” Mr. Matheson said.

“No,” Prudence squeaked, her voice sounding desperately close to a whimper. “Please don’t—”

“Turn about and walk to the stand of trees just beyond the rocks. No one will see you there, and if they do, you’ll be at too great a distance for anyone to determine who, exactly, you are.”

“I can’t—”

“You can’t stand here hiding behind me, Miss Cabot. It’s entirely suspicious. Go, and I’ll walk behind you and block any view.”

Prudence lifted her cheek from the warmth and safety of his back. He was right, of course; she couldn’t hide like a dumb cow in the middle of a meadow. She glanced at the trees Mr. Matheson had suggested.

“Miss Cabot?”

“Yes,” she said quickly, earnestly.

“Let go of my coat and turn about.”

“Oh. Yes.” She reluctantly released his coat and tried to smooth out the wrinkle she’d put in the fabric with her grip.

Mr. Matheson hitched his shoulders as if she’d tugged him backward, and straightened his cuffs. “Have you turned about?”

“Ah...” She turned around. “Yes.”

“Then for God’s sake walk on before the passengers begin to wonder why I stand like a damn tree in this field.”

Prudence did as he instructed her, her hands clasping and unclasping, her step light and very quick, trying not to run. She didn’t dare look back for fear of Dr. Linford seeing her. When she reached the safety of the trees, she whirled about and collided with Mr. Matheson’s chest.

He caught her elbow, his grip firm, and dipped down to see her beneath the brim of her bonnet. His gaze was intent. Piercing. It felt almost as if he could see through her. “I’m going to ask you a question and I need you to be completely honest with me. Are you in trouble?”

“No!” she said, aghast. Not as yet, that was. “No, no, nothing like that.”

“Do you swear it?”

Good Lord, he acted as if he knew what she’d done. Prudence looked away, but he quickly put his hand on her cheek and forced her head around to look at him. She opened her mouth to respond, then thought the better of it and closed it. She nodded adamantly.

He unabashedly continued to study her face a moment, looking, Prudence presumed, for any sign of dishonesty, which made her feel oddly vulnerable. She looked down from his soft golden-brown eyes and dark lashes, from the shadow of his beard, and his lips. His lips. She was certain she’d never seen lips like that on a man and, even now, as terrified as she was of being discovered, they made her feel a little fluttery inside.

“Stay here,” he said. He strode away from her, toward the carriage.

When he reached the small crowd, there was a lively discussion, the center at which seemed to be Mrs. Scales. Mr. Matheson gestured toward Linford’s carriage. Mrs. Scales bent over and grabbed up her pail and a bag, and hurried toward the Linford coach. Her sister was quickly behind her, dropping her pail once and quickly retrieving it. But at the coach door, there was another discussion.

There was a shuffling around of the luggage, and then Mrs. Scales, Mrs. Tricklebank and the elderly gentleman all joined Dr. Linford and his wife in their coach. Dr. Linford climbed up to sit beside his driver. After what seemed an eternity, Dr. Linford’s coach drove on, sliding around the stagecoach, and then moving briskly down the road.

Prudence sagged with relief. A smile spread her face as she realized she had managed to dodge Dr. Linford completely. How clever she was! Prudence had never thought herself capable of subterfuge, but she appeared to be quite good at it. She felt oddly exhilarated. At last, something exciting was happening in her life! It was only a single day, but she was completely enlivened by the events thus far.

Now that the Linford coach had gone, Prudence noticed Mr. Matheson began striding toward her, his gait long and quick, his tails billowing out behind him.

She couldn’t see the harm in this, really. She’d had her lark with a handsome pair of eyes and stirring lips, and no one would be the wiser for it. She would arrive at Cassandra’s house as intended, and none would be the wiser of her flirt with adventure, would they?

Prudence might have strained her arm reaching about to give her back a hearty, triumphant pat, but she had a sudden thought—Mrs. Scales or Mrs. Tricklebank could very well say her name to Mrs. Linford, who would know instantly what she’d done, and worse, that she’d purposely eluded Dr. Linford in this meadow as if she had something very dire to hide.

Prudence went from near euphoria for having arranged an escapade she would long remember to terror at having done something quite awful. Now what was she to do?