Читать книгу Race Man - Julian Bond - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

The Love Endures

Pam Horowitz

Michael Long’s book is aptly named. Julian himself wrote only one book—A Time to Speak, A Time to Act—published in 1972. In it, he wrote, “I must admit to a certain prejudice, a bias that is race. Most of my life has been colored by race, so much of my thinking focuses on race.”1

Julian was a “race man” in the mold of Thurgood Marshall, who “became what blacks of the 1930s admiringly called ‘a race man’: a black man whose major work was to advance the interests of his race.”2

That this would be Julian’s work is not surprising, given his family history. His paternal grandfather, James (whose name always gave Julian pleasure in the telling), was born a slave in Kentucky in 1863. Julian loved to recount that James hitched his tuition—a steer—to a rope and walked across Kentucky to Berea College, and the college took him in. When he graduated in 1892, it is believed “that he was one of only 2,000 blacks in America to have a college diploma, demonstrating his strong nature to overcome.”3 The original James Bond would go on to earn a doctor of divinity degree.

Julian’s father was the noted educator, Horace Mann Bond, who graduated from Lincoln University at the age of 19 and received his PhD from the University of Chicago. Lincoln University, known in its early years as “the black Princeton,” included among its notable alumni Langston Hughes and Thurgood Marshall, along with the first president of Nigeria, Nnamdi Azikiwe, and Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana. In 1945, when Julian was five years old, Lincoln would hire his father as its first black president.

Julian’s mother’s family was equally distinguished. Born Julia Washington, she graduated from Fisk University, as did both of her parents and her sisters. Her parents and one sister were educators. Another sister was a social worker, and her only brother was a doctor. After earning a degree in library science when she was 56, she published a book at the age of 89 and retired at 92!

With this pedigree, one can imagine his parents’ reaction when Julian quit Morehouse College one semester short of graduation to join the nascent civil rights movement. (He would receive his Morehouse degree ten years later—in 1972.)

Julian liked to quote one of his heroes, Frederick Douglass, who said: “He who would be free must strike the first blow. You know that liberty given is never so precious as liberty sought for and fought for. The man who is outraged is the man who must make the first outcry.”4

When Donald Trump was elected, I knew that Julian, in Douglass’s spirit, would tell us, “Don’t agonize, organize.” Throughout his life, Julian was among those who would “strike the first blow” with respect to the major issues of his time.

A gathering at Shaw University over Easter weekend 1960 would mark the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Julian would become SNCC’s communications director, putting him in the vanguard of the movement.

“Unlike mainstream civil rights groups,” Julian wrote, “which merely sought integration of blacks into the existing order, SNCC sought structural changes in American society itself.” Julian proudly added that President Carter said, “If you want to scare white people in southwest Georgia, Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference wouldn’t do it. You only had to say one word—SNCC.”5

True to its character, SNCC would issue a statement against the Vietnam War in January 1966—well before most others did so.

Julian was a candidate for the Georgia House of Representatives at the time. As SNCC’s communications director, Julian endorsed SNCC’s statement. That ultimately would lead to the refusal of the Georgia House to seat him when he won the election, sending Julian to the United States Supreme Court and national fame.

SNCC’s antiwar statement charged the United States with being “deceptive in claiming concern for the freedom of colored people in such other countries as the Dominican Republic, the Congo, South Africa and the United States itself.”6 In March 1966, seven SNCC workers, including Julian’s brother James, “were arrested at the South African Consulate in New York, preceding by twenty years the ‘Free South Africa Movement’ that later saw hundreds arrested at the South African embassy in Washington.”7

Julian himself would be one of those arrested at the South African embassy in Washington. His last arrest came in February 2013 when he and environmental leaders protested against the Keystone Pipeline at the White House.

In keeping with a lifetime of “making the first outcry,” Julian was an early and passionate supporter of the equal rights of LGBT Americans, insisting that “LGBT rights are human rights.”8 Eventually, in May 2012, his influence would help the NAACP adopt a resolution in favor of marriage equality.

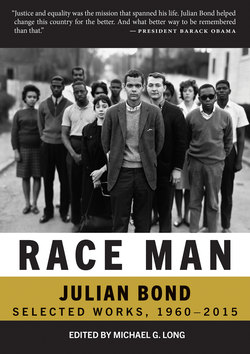

As President Obama said at the news of Julian’s death: “Julian Bond helped change this country for the better. And what better way to be remembered than that.”9

Julian wanted to be remembered with a bench, with “race man” on one side and “easily amused” on the other. To me, that captures Julian: he did the serious work of being a race man buoyed by having a sense of humor.

Julian also possessed an amazing intellect, sensitivity, grace, and elegance, not to mention incredible good looks. My marriage to him was the gift of a lifetime.

Julian and I went to the Supreme Court argument in Obergefell v. Hodges in April 2015, as guests of the Human Rights Campaign. We stood in line with Chad Griffin, our friend and HRC president, and Jim Obergefell, the plaintiff whose case we hoped would grant gays the right to marry. These hopes were realized on June 26, 2015, when the Court upheld marriage equality, saying: “No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. . . . In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. . . . Marriage embodies the love that endures even past death.”10

Julian would die less than two months later. The love endures.

August 2018