Читать книгу Race Man - Julian Bond - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

Practicing Dissent

Jeanne Theoharis

“What do you think about the Greensboro sit-in?” a fellow More-house student Lonnie King inquired [to then-twenty-year-old Julian Bond].

“I think it’s great!”

“Don’t you think it ought to happen here?” he asked.

“Oh, I’m sure it will happen here,” I responded. “Surely someone here will do it.”

Then to me, as it came to others in those early days in 1960, a query, an invitation, a command:

“Why don’t we make it happen here?”

I heard Julian Bond, one of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s founding members, tell this story countless times. He probably told it hundreds of times over the course of his life. It was not merely autobiographical in detailing how, as a college student, Bond came into civil rights activism. In the way he told it, he provided a lesson about how hard it is to step into social justice work. Like most of us, Bond admired courageous action but assumed someone else would take it forward; and then he realized his own power—and imperative—to act. In this story, in his graceful way, he holds a mirror to our collective tendencies to admire courage but stand on the sidelines.

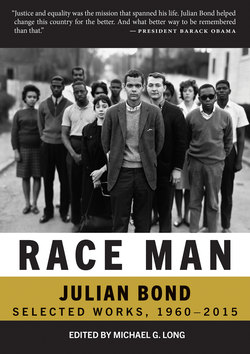

Julian Bond died in 2015 at the age of seventy-five. While a student at Morehouse College, he had been a founding member and then communications director of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. SNCC’s courageous direct action transformed the systems of racial inequality in voting, jobs, schools, and public services in the South—and the ways local people saw their own power. Elected to the Georgia state legislature in 1965, Bond was then denied his seat because of his opposition to the Vietnam War; he fought and won it back twice and served for twenty years, first in the Georgia state house and then in the state senate. Continuing his commitment to social justice, he served as the first president of the Southern Poverty Law Center and as chairman of the NAACP. And for nearly 25 years, he also taught at Williams College, Drexel University, the University of Pennsylvania, Harvard University, American University, and the University of Virginia. The speeches and writings gathered here encompass much of that history.

Embedded in this personal story about helping to spearhead the Atlanta sit-in and many others he told about the civil rights movement were larger lessons about social justice, about how hard it is to take a step forward and the factors that lead people to see their own power and responsibility to do so. In many of these speeches, as he details the civil rights struggle from Atlanta to Jackson to Boston, Bond vividly underlines how real people had to make extremely difficult decisions. Despite the ways the civil rights movement is celebrated today, there was nothing inevitable or obvious about it. America wasn’t naturally moving toward justice. People chose, amid searing conditions, amid threats to their person and their livelihood, to make it happen.

The point of his lectures was not just to tell stories—though, of course, people could listen to those stories for days—but to impart broader insights about how history changes, about the nature of injustice and the forces that protect it, and about our role in challenging it. As this collection demonstrates, one prominent theme was the role of young people in pushing farther than their elders: “The student movement came about because young people saw many of their elders refusing to cope with segregation adequately. They saw other youngsters younger than they in Little Rock and other cities face mobs who would have deterred many a seasoned fighter. . . . They saw, finally, that it does no earthly good to talk and fret about segregation and that only action will enable man to talk of segregation as a thing of the past.”11 Bond reminds us how youth action was treated with fear and trepidation a half century ago, paralleling the ways young activists are treated today. “People in the press were always suspicious of us—they thought we were either communists or crazy kids—and because their concern was with brutality, with the big sensationalism. They weren’t interested in writing about the day-to-day work that SNCC was undergoing from 1961 through ’64 and ’65.”12 In other words, SNCC’s young organizers were treated as reckless and dangerous and going too far too fast, while at the same time the groundwork they were building in local communities was ignored—a parallel to how many commentators, politicians, and news outlets treat Black Lives Matter today.

Bond served as SNCC’s communications director—a position that furthered his belief that what is told and how it is told is crucial both to present-day mobilization and to the histories that will be preserved. Time and again, Bond tried to set the record straight. About the power of Fannie Lou Hamer and the refusal of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to be kowtowed by their supposed allies: “When offered a dirty deal by high representatives of the Democratic Party in Atlantic City in 1964, she turned them down flat, saying ‘We didn’t come for no two seats, ’cause all of us is tired.’”13 About the transformation of the War on Poverty to a War Seeking to Uplift (and Chastise) the Poor: “But the worst damage was done when the victim was made to feel part of the crime, when the people wronged were told to set themselves right, when the federal government began a hasty and undignified withdrawal from its role as protector of the poor.”14 Bond was clear that one of the most effective weapons in maintaining injustice was to make people feel like they were the problem and to make others comfortable in asserting that these “cultural” behaviors and values (and not racism) were the problem.

Bond didn’t mince words, calling for “reparations to the tune of $15 a nigger” to be used for a land bank, publishing house, welfare rights and a host of other social initiatives. Describing black people’s “colonial” status, he noted, “It didn’t take a Kerner Report for black people to discover that white people were our problem, and not we theirs.”15

He maintained his sharp engagement in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, engaging with a variety of issues—criminal justice, gay rights, affirmative action, new US wars and military involvements, and gangsta rap—insisting that his position as chairman of the NAACP necessitated such engagement. He was scathing about Reagan’s wide-ranging attacks on the poor and civil rights. His ideas evolved—from placing women’s and gay rights as somewhat apart from black issues to becoming an adamant champion of gay rights and seeing their interlocking nature. At one point in 1977, he critiqued some of the behaviors of black young people, but that theme does not reappear again in his speeches, perhaps because he saw the dangerous ways such a critique could be misused. Bond read and reflected. He learned and learned some more, writing op-eds, joining picket lines, and standing with movements across the United States. He was still in the fight till the end, embodying Rosa Parks’s belief that “freedom fighters never retire.”

The last time I saw Julian Bond in a political context was at the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer in Jackson, Mississippi, in June 2014. He was on a panel with current activists from the immigrant rights DREAMer movement as well as the criminal justice oriented DREAM Defender movement. Unlike some of his generation who sought to instruct young people on the “right” way to do things, Bond relished that youthful energy and drive. Like SNCC’s mentor Ella Baker, he saw student militancy as essential, remembering how they too had made people scared and wary.

That spirit of identification and encouragement came through in his teaching and in the lectures he did at many colleges. Vann Newkirk recalled Bond’s visit to his class at Morehouse College in a piece in the Atlantic, “He told us that while the enemy—racism—was the same, the battlefield had changed. To carry on the movement, we would have to be modern warriors. We would have to adapt and innovate for the times. Maybe we would have to let go of some of the respectability, he said. . . . There’s one line I remember verbatim: ‘A nice suit is a nice suit. Get one,’ he told us. ‘But it won’t stop a bullet, son.’”16 From Bond, Newkirk saw the continuities and lineages between the black freedom struggle of the 1960s and Black Lives Matter today—and the ways public memory of the civil rights movement distorted it to make it seem at odds. To the end of his life, Bond sided with young people, trusting them to find their own way forward and standing with their vision and spirit.

Forty-four years before the election of Donald Trump, Bond observed, “If the election of November 7th illuminated any political movement at all, it was the movement of the comfortable, the callous, and the smug closing their ranks, and their hearts, against the claims and calls to conscience put forward by the forgotten and underrepresented elements in American society. . . . There is something wrong with an election that sees one candidate receiving nearly all of the black votes cast, and the other candidate receiving more than three-quarters of the white votes cast.”17

His words continue to be prescient today—reminding us that what we face today has been faced by others before us, and reminding us of the tools they used to challenge it. As does his example of refusing to stand on the sidelines in these dangerous days. “We must practice dissent now,” he insisted.18 Young people will lead the way.