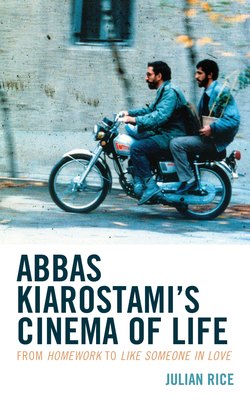

Читать книгу Abbas Kiarostami's Cinema of Life - Julian Rice - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Saving the World

ОглавлениеKiarostami’s work often reflects Sufic pantheism, but at times it evinces a dualism that has its roots in the pre-Islamic religion of Iran. Founded by the prophet Zarathustra in about 1500 BCE, Zoroastrianism was the official religion of Iran at the time of the Arab conquest in 651 CE. Unlike Christianity and Islam, it was not aggressively conversionary, and during the time it was the state religion, the Persian king Cyrus the Great (630–530 BCE) allowed the people in his subject territories to retain their own religions, most notably the Jews, whom he allowed to return to Israel after a half-century in Babylonian exile. Perhaps tolerance is an attribute of Zoroastrianism because, unlike Judaism, Christianity, or Islam, its primary deity is not omnipotent. Ahura Mazda represents the creative force of the universe, and he is assisted by thousands of spirits called fravashis against his destructive adversary, Angra Mainyu, also called Ahriman.

Good in general means protecting the physical world against Ahriman’s work of war, pestilence, and natural disaster, and each human being assisted by a fravashi as his or her guardian spirit is sent into the world as a kind of undercover agent to report vital information for the ongoing battle after he or she dies. In the Persian rather than the Islamic tradition, the good Kiarostami sought to further was more in line with asha, the Zoroastrian way of good thoughts, good words, and good deeds, rather than in absolute obedience to a salvific faith and its theocratic agents.[1] There is a Cain-and-Abel distinction in Where Is the Friend’s House? but there and in subsequent Kiarostami films (as well as those of Makhmalbaf and Panahi), obeying the laws of the state is usually the just-following-orders way of Ahriman. Ahmad’s grandfather is on a continuum with Nazis and terrorists, people whose problems are solved by not having to think, or as one Al Qaeda recruit put it, “Jihad is the cure for depression.”[2]

Hamid Dabashi writes that Iran’s “autonomous literary imagination” stemmed from Zoroastrian roots. After the seventh-century Arab conquest, “Arabic became the paternal language of the hegemonic theology, jurisprudence, philosophy, and science,” while Persian remained the language of “mothers’ lullabies and wandering singers, songwriters, storytellers, and poets, [constituting] the subversive literary imagination of a poetic conception of being.”[3] In the first two centuries after the conquest, the Arab rulers sensed this undercurrent as an existential threat, and the later proponents of the folk tradition who preferred this world to the next, like Omar Khayyam and the doctor in The Wind Will Carry Us, were considered “licentious, dissolute, profligate, wicked, shameless, and just plain morally corrupt.”[4]

The Islamic word for these perceived degenerates is Zanadiqa, a term derived from Zend, the language of the Avesta, the Zoroastrian holy book and its commentaries. Near the end of the eighth century, a chief inquisitor burned these books and crucified their unrepentant devotees.[5] But despite periodic suppression, holidays with Zoroastrian roots are still alive in Iran, the most notable being Nowruz, the Iranian national New Year celebrated on the first day of spring. The most significant Zoroastrian vestige, however, is an item of jewelry, the faravahar pendant. Perhaps because it is exclusively Iranian, predating the Muslim conquest, it is a symbol of national pride, the most-worn pendant in Iran. It depicts a bearded human figure in left profile rising from a central disc flanked by the spread wings, legs, and tail feathers of a powerful bird resembling that of a Native American thunderbird. The man’s right hand points upward, and his left hand holds a large ring.[6]

The faravahar is commonly thought to be the image of a winged fravashi. Although the Islamic revolution of 1979 removed some Persian symbols that the shah had elevated to strengthen Persian nationalism, the faravahar was not banned, even though it was not religiously rooted in Islam. In fact, Iranian Islam, for the most part, opposes any religious expression that threatens to substitute an angel or a Sufi saint for Allah. In the Avesta, Ahura Mazda states that he created the physical world in concert with “many hundreds, many thousands, many tens of thousands [of] mighty, victorious fravashis” and that without their help Ahriman would have possessed all of humanity.[7]

Since then, the fravashis continue to guard each human being, as in the doctor’s recitation from The Wind Will Carry Us: “If my guardian angel is the one I know, he will protect glass from stone.” The sentiment is potentially blasphemous in Islam because if a person dies believing that God is associated with or equal to some other entity, he or she will be permanently consigned to hell. While a Muslim (or a Christian or a Jew) seeks to obediently please a paternal God, a Zoroastrian has the cooperative role of a vital helper.

Sufism, too, was targeted by orthodox religious authorities for its presumed equalizing of human beings with God. In 922, the Sufi philosopher Mansur Al-Hallaj was executed in Baghdad for pantheistically saying, “I am the Creative Truth,” which was interpreted to mean “I am God.”[8] Other Sufis, in the orthodox view, presumptuously say they are close “friends” of God. In twenty-first-century Iran, Sufi devotion to the revelations of their saints and their emphasis on personal religious experience has been attacked as undermining the Islamic republic’s “governance of the jurist,” which strictly adheres to the Koranic laws as interpreted and sanctioned by state theologians. As a result, Sufis have been banned from government jobs, and some of their religious structures have been bulldozed. In 2006, a Sufi who publicly protested mistreatment by a government official was flogged seventy-four times.[9]

But while the Sufi sentiment that most offends the inquisitorial mind could be so harshly punished in a low-ranking, anonymous person, it had already been enshrined in the country’s culture by one of the nation’s most honored poets. In “The Creed of Love,” Rumi wrote of a seeker who was refused entrance at the “door of the Beloved” because he made a distinction between himself and the One he sought: “A voice asked, ‘Who is there?’ / He answered, ‘It is I.’ / The voice said, ‘There is no room for Me and Thee.’ / The door was shut. / After a year of solitude and deprivation he returned and / Knocked, / A voice from within asked, ‘Who is there?’ / The man said, ‘It is Thee.’ / The door was opened for him.”[10]

All Muslims hope for this closeness in Paradise, but Sufis strive to achieve it in their earthly lives through visions that include colors and sounds. In this sense Kiarostami’s cinema may be considered Sufic, but his philosophy of filmmaking expressed in the self-made documentary Ten on Ten stresses the equivalent of Zoroastrian partnership. Until the last chapter, the film places us in the passenger seat of a car Kiarostami is driving on the outskirts of Tehran over the same winding roads driven by Mr. Badii, his suicidal protagonist in Taste of Cherry. He explains that some viewers of Ten, shot entirely in a car passing through Tehran traffic, said they missed the landscape settings of his previous films, and so in sympathy with people stuck in the mental gridlock of their busy lives, he has brought them to a place he loves, especially because rapid urban development may soon make it impossible to return.

But he also says that the present journey is not about specific social problems but about a “relationship” that he does not specify. In the course of the film, this relationship proves to be a cooperative one between members of a group and their lack of subjection to a central authority. For Kiarostami, absolute directorial control creates unnatural cinema. He breaks the fourth wall in the coda to Taste of Cherry because he wants to show people acting naturally, and over the course of his career, he stopped using the clapper board and saying, “Sound, camera, action” (a routine satirized in Through the Olive Trees), because it would make his nonactors stiffen up and overact.

Experience taught him that a “master-servant relationship does not work in cinema,” and instead of using his DV camera “like a God” to dictate his actor’s every move, Kiarostami made them beings of independent will, a relationship he paraphrased after quoting the previously cited lines by Rumi: “He says, you are my polo ball, and you run before my mallet, and I run after you, although I made you up, [which] means that I pushed you forward, but now I need to follow you. Eventually I will take it to the end, but you’re the one who determines how to get there. I just determine the direction.”

Kiarostami further limits the director’s role by explaining that both of the French terms for auteur—metteur en scène and réalisateur (one who gives order to the scene and one who realizes something)—are too pretentious to describe what he does: “In the end credits, I list the names of those who worked on the film without mentioning their functions. I have never realized anything. Never been a réalisateur. Reality was constantly being played in front of me. I was merely there to record it.” At the same time, even “God-given” realities may be imaginatively altered: “If one pictures a green sky, you can see the sky in a new way.” This directorial style has metaphysical implications regarding the improvisatory roles of God and man, Ahura Mazda and human beings. Working together they can create something unpredictably beautiful, but human beings are likely to become destructive if they lack an overview of their connection and remain locked inside themselves.

Kiarostami explains that he uses the frequent device of placing his camera inside a car to reveal an intimacy that is more apparent than real:

A moving car creates a sense of security for me personally. I imagine my voice getting lost among the noise of other cars. And these iron cells give me a sense of security [that] facilitates my inner dialogue. I insist on hearing my own voice in this dialogue. A person sitting next to someone else might not even pay attention to the other’s presence. Each of them narrates his or her own inner world, . . . and this we owe to the confining cell that is the car.

The other confinement that Kiarostami hopes to break is the Hollywood formula for commercial success that preoccupies the brain so that spectators cannot think: These films try to “move them, reduce them to tears, laughter, and fear, [to] use every instrument at [their] disposal to captivate the audience. This is the secret behind the success of American cinema.”

Then, paraphrasing the advice of an unnamed friend, he ironically adds, “American cinema has not become successful without good reason, and neither has America. If you want to be a successful filmmaker, I suggest that you never forget the formula of American cinema.” At this point he stops the car and yanks the parking brake with a decisive sound, as if he were putting an abrupt end to abstract caution. It is time to escape the iron cells of urban distraction, addictive cinema, and the cult of the ego that confuses celebrity with creation.

After telling the viewers they can now stop looking at his “ugly yap,” Kiarostami turns his back to the camera and says, “Now, take a look at some scenery, while I turn on the camera on the other side.” Then he gets out and emphatically slams the door. In place of Kiarostami’s profile, the film’s predominant image, the view out the driver’s window from the passenger side shows only trees rippling in the breeze, and in place of his voice, we hear only the wind and sea. After a moment we hear him say, “I’d like to show you something which reminds me of a Japanese haiku.”

The camera now moves across the dashboard and out the open passenger door, as if the viewer were getting out. Then, below the passenger windows, it moves toward the back of the car, until it leaves the car altogether. The car’s shadow remains to the right of a frame showing a sunlit dirt road with a grass border on the bottom and a tree on a hillside at the top. Finally, as the sound of Kiarostami’s footsteps crunch on small stones, even the car’s shadow disappears, giving way to a tall pine on a hill with a vista of land and sea behind it. Then the camera shifts to the right, keeping the tree but showing a jutting hill with two small trees, each subtle but significant camera shift comprehending more beauty. The camera returns to the road as Kiarostami begins to speak for the last time in the film: “The cedar tree atop the hill / On whom does it pride itself.” The words suggest that the spirit of Creation makes no distinction between great and small.

Even in a world dominated by those confined to their iron cells, other human beings can foster a spirit of generous cooperation. The camera comes closer to the ground, where a small strip of dirt road lies just below the gray shadow of the car, which again covers most of the frame above. Kiarostami continues, “And something else: Light the fire, and I’ll show you something.” The camera moves down again, until an anthill appears in the center of the frame, just as Kiarostami says that the “something” that he will show will be “invisible if you don’t wish to see it” and unheard “if you don’t wish to listen to its breath.” Now the camera moves to a close-up of the anthill opening, where ants are seen moving all around. But then a corncob carried by a single large ant enters the frame from the left. When it is almost at the hole, another ant emerges from inside and tries to help, but the big ant backs into the hole and pulls the corncob after it. A third ant on the outside gives it a final push.[11]

That is the story Kiarostami wished to tell by a fire that only the attuned spectator can light. The screen goes black with the white lettered words “Abbas Kiarostami,” followed by cards (rather than rolling credits), each containing the name of a Ten on Ten crew member without naming their separate jobs. If we are to further the spirit of Creation in our collective life, everyone’s contribution must count, and no God, leader, or celebrity can do it for us. This is especially true of our responsibility for the earth’s environment, and the Zoroastrian legacy most evident in Kiarostami is the religion’s emphasis on the supreme value of the physical world.

For the two thousand years of its ascendancy, Zoroastrian Persia framed this vision in a walled garden, a practice that has survived the Arabization of Iran’s culture. A Persian proverb reads, “Whoever creates a garden becomes an ally of Light; no garden having ever emerged from the shadows.”[12] The garden represents the unity of Creation that Ahriman seeks to divide. Human beings were created as the last and seventh creation to maintain the purity of the first six: sky, water, earth, plant, animal, and fire.

The rigor of this responsibility, microcosmically expressed in making the garden, was no easy task in the desertlike conditions present in most of Iran’s interior. But it was worth the cooperative effort of many hands to instill the serene strength needed to resist the anxiety and anger Ahriman depends on. The garden’s wall corresponds to Kiarostami’s understanding that “we are not able to look at what we have in front of us unless it is inside a frame,” and paradoxically, we need a frame to experience a spiritual essence that cannot be contained by sight and sound. And so the garden was a way of creating an enclosure that transcended all enclosures, a fairly clear analogy to a Kiarostami film. Inside the garden’s “frame,” sunlight, shade, and water nurture all kinds of shrubs, flowers, and trees, especially such evergreens as cedar and cypress, because they affirm the continuity of creation, while the garden as a whole represents the purpose of all human effort.

The other Zoroastrian frame derived from and coequal with the garden is that of the bijar (tree of life) carpet, which violates the Islamic ban on the graven image and which Kiarostami lovingly explores in a six-minute film originally called Is There a Place to Approach but retitled Rug on the 2010 Shirin DVD. The original title approximates the words on the black-and-white title card: “Where is the place to reach / And spread a rug to settle?” by Sohrab Sepehri, whose poem “Address” had inspired Where Is the Friend’s House? Unlike that film, which depicts the Zoroastrian adversary through the grandfather and the window dealer, Rug is a vision of Sufi unity, but the primary image it uses to express its vision is rooted in a Zoroastrian reverence for nature. The film begins with the camera moving up over a green-and-gold rug with a tree in the center containing pale blue birds. Their chirping harmonizes with the voice of a woman reciting Sepehri’s words: “Open your eyes to see the lover’s beauty glowing everywhere. / Observing this vision makes you think / There is no other than He, the Creator.”

Then the camera begins to move right to left along the top border, which has a stylized row of upright cone-shaped canopies in gray, gold, and blue, alternating with small, triangular green trees shaped like candle flames with open centers above an upright candlestick. Fire and trees are especially sacred in the Zoroastrian tradition, and each small tree has an identical one above it, resembling, perhaps the fravashi guardianship of each human person. When the camera reaches the left edge, it moves down to the bottom border, then right, and up again, completing a counterclockwise circuit.

As the camera moves, we see elaborate images of imaginatively shaped and fantastically colored birds and trees, while a male and female voice alternately read a love poem, first to each other and finally to all of Creation. Romantic love becomes spiritual love as we move from the female voice recalling how she and her lover “sat by a stream in absolute silence” and the male voice recalling how they sang “love songs by heart” to all the human and nonhuman beings that surrounded them: “The tree blossomed and the nightingales delighted. / The world got young and fresh / and lovers gathered with joy.”

These lovers include the couple in the poem as well as the poet, the rug’s weaver, and the filmmaker who love the source of their inspiration and the means they have found to express it. The poem’s metaphysical theme comes through as the male voice describes a festival, where “The green grass was trampled / under joyous steps / when all Gnostics and illiterates started dancing together.” The choice of Gnostics stems from their theologically elaborate separation of matter as evil from spirit as good, a dualism adopted in the third century CE by the Persian prophet Mani. His doctrine, often blurred in modern English by the commonplace “Manichean” to mean any form of dualism, altered the Zoroastrian fight to preserve the physical world, which is considered an absolute good, to the primordial struggle of ethereal spirits to free themselves from physical bodies, which are considered primarily bad.[13]

In opposition to any religious tradition that strives for “upward” purification, Kiarostami concludes Rug by moving the camera down into a celebration of physical nature and then back up, not to transcend it, but to convey the mystery of its source. After completing his overview by circling its borders, the camera descends to a tall tree at the center of the rug. It focuses for a moment on a large blue-and-gold bird and then moves to a fanciful green one with an eight-pronged crest and large tail stylized into nine gold circles. The images suggest the presence of spirit in matter by being simultaneously strange and familiar. Then the camera slowly moves down the surface of the rug and then back up, relishing each abstract pattern of green and gold and each embodied image of a branch, flower, or bird. As it does, a solo violin signals the approaching end with a melody that is both lyrical and piercing, an effect softly intensified by a drum that sounds like a heartbeat.

During the upward movement, the male voice repeats the verse spoken at the beginning by the female voice, where the romantic expands to the spiritual: “How good was that day / under the willow tree?” The woman continues, “Next to a stream, I was sitting with my heart. / We were singing love songs by heart. / We were singing love songs by heart, / and we were sitting in absolute silence.” When the camera reaches the golden tree at the center, it pulls upward into space, exposing misty green branches outside the rug’s borders. Some of them begin to sway in the breeze, implying in typical Kiarostami fashion that translating nature into art exists to return us to nature with a renewed sense of appreciation and love.

The camera rises until the rug appears suspended in space, but the swaying trees remain around and behind it. They are not transcended, and they do not disappear. White swirls around them lend a magical effect, as if winter snow were swirling above green summer grass. While the camera holds on this image, the music is replaced by the woman’s voice: “Be happy and delightful, always.” The screen slowly fades to black, and as if to praise universal rather than specific creation, there are no closing credits.

Rug progressively illuminates Sepehri’s two lines on its title card—“Where is the place to reach / And spread a rug to settle?” By the end, the rug’s weaver and Kiarostami’s camera have shown that the place to settle is the natural world in the present life. Elena says that Sepehri’s poem “Address,” which ends with the line “Where is the house of the friend?” “subscribes [to] a tradition of mysticism, of remote Sufi inspiration.”[14] Rug and Roads of Kiarostami, another short film that Kiarostami made about the same time, are both strongly influenced by Sepehri, Sufism, Taoism, and Buddhism.

Referring to Puya, the young son of the director in And Life Goes On, as the film’s figure of wisdom, Kiarostami said, “In Eastern philosophy we believe that you need a guide before you set foot in unknown territory,” and he repeatedly identified Sepehri as one of his own guides by quoting him in interviews and in his films. He also spoke of the need to see the world with “borrowed eyes,” to take his viewers “outside the scene [they’re] looking at, to see what is there and also what is not there.”[15]

Using one of his prominent metaphors for getting “outside,” Kiarostami gets out of his car at the end of Ten on Ten to train his camera on an anthill, which he says reminds him of a “Japanese haiku.” What is “not there” in that scene is the authoritative voice. What is there is the merged movement of spirit in some of the earth’s smallest creatures. Sepehri, who was also a major Iranian painter, anticipated Kiarostami in striving to express a spiritual presence, and while his poetry derives much of this presence from Sufism, much of his painting looks further east. He translated Japanese poetry in the mid-1950s, and in his introduction to a collection of these poems, as described by Houman Sarshar, Sepehri praises the Eastern perspective for its “connection with the organic laws of the cosmos [that were] overtly cultivated by the values and nuances of their ancient myths and pervading philosophies.”[16]

In 1960 Sepehri learned woodblock printing in Tokyo from the renowned Unichi Hiratsuka (1895–1997), and for the next fifteen years, he produced a series of landscapes known in Iran as his Far Eastern phase. These paintings, in Sarshar’s view, express the “primal unity of the cosmos” by abstracting natural phenomena: “That which is not painted thus reflects the imperceptible, indiscernible mystery of a unified universe; that which is painted, reflects the boundaries of our perception.”[17] In one notable series, the “paintings depict clusters of tree trunks in tight closeups that leave branches and foliage out of the frame.”[18]

Sarshar’s summation applies as much to Kiarostami as it does to Sepehri: “In his vision of the world and of mankind’s place within it, Sepehri believed above all in the importance of people’s direct relationship with nature, [and he was] unwavering in his belief in a delicate yet essential unity between mankind, nature, and a greater cosmic order.”[19] From Taoism he learned

to believe in an essential oneness between mankind and nature, . . . to see nature as an undifferentiated consubstantial whole in which each constitutive part reflects the organic laws of the great cosmic order . . . [and] in Zen Buddhism he found the value of a constant and consistent meditative self-contemplation; of living in the here and now; of extracting simplicity from complex paradigms and expressing complex thoughts in the simplest, most economic fashion possible.[20]

These worldviews, in conjunction with Persian Sufism, which finds the “contemplation of subtle beauties of the natural world [to be an] ideal venue for arriving at a first-hand experience of the divine,” contributed to Sepehri’s mature belief “that while a higher unifying truth was innate in all of creation and the knowledge of it intuitively available to all mankind, a conclusive understanding of it was impossible in an individual’s lifetime and the search for it a lifelong journey for all.”[21]

The search in Roads of Kiarostami may not be spiritually conclusive, but undertaking it has become urgent in a way that Sepehri did not foresee. The film’s slow, peaceful ascent on mountain roads ends with a shock that could be the end of the road for everything the camera lovingly shows. In an interview, Kiarostami distinguished his cinema from his photographs, which were exclusively “focused on the environment and nature,” except for the previously described “walls and doors that show the effect and the impact of nature on human beings.” He also spoke indirectly of the Eastern relationship between artist and subject: “In my photography I have tried to remove myself as a barrier between the audience and the subject” and to instill an empathy that would help to preserve the natural world he loved. Although it was difficult to think about, he feared “what will happen to nature when I leave this life.” A friend tried to reassure him by reminding him of the coda to Taste of Cherry, which projects a “time [to] come when soldiers will have flowers in their hands as opposed to guns.”[22]

Although Eastern philosophy and Sufism seek to merge the individual with the all, Kiarostami realized that to be a guide for others whose cultures do not encourage such union, he would need to alter their reality because art exists to break up existing realities and create new ones.[23] Roads of Kiarostami was produced by a South Korean environmental group for the Green Film Festival in Seoul, and it expresses a wisdom accumulated from Persian and Japanese poetry to address the nuclear threat in a way similar to that of Pope Francis in Laudato Si, his 2015 encyclical on global warming. Kiarostami’s photographic and cinematic treatments of nature show that he shared the pope’s view of art’s purpose:

The relationship between a good aesthetic education and the maintenance of a healthy environment cannot be overlooked. By learning to see and appreciate beauty, we learn to reject self-interested pragmatism. If someone has not learned to stop and admire something beautiful, we should not be surprised if he or she treats everything as an object to be used and abused without scruple. If we want to bring about deep change, we need to realize that certain mindsets really do influence our behavior. Our efforts at education will be inadequate and ineffectual unless we strive to promote a new way of thinking about human beings, life, society and our relationship with nature. Otherwise, the paradigm of consumerism will continue to advance, with the help of the media and the highly effective workings of the market.[24]

The mind-set that Kiarostami most hoped to change is how cultures envision God. His God is an artist rather than a king or a judge. Nature is seen as God’s weaving in Rug and as God’s poetry in Roads. The film includes poetic passages by Kiarostami and Sepehri that correspond to visual and musical elements working together in a synesthesia that transcends any single voice. Kiarostami takes his viewers on a trip to the mountains, where (as in Ten on Ten) getting out of the car at the end signifies escaping the viewer’s cultural frame. The film moves from the aesthetic elaborations of Sepehri to a visual version of the haiku-like images that Kiarostami verbally employs in poetry.

At the lower levels, Kiarostami travels a well-paved road in the flat land, leaving people engaged in everyday work, a man with a herd of sheep and another with a bale of hay loaded on a donkey. The vistas are wide, and the andante movement of a classical horn concerto creates a contemplative mood, immersing the viewer in the scenery and the moment. After the first five minutes, he begins to speak, recalling how he initially turned to nature just to be peacefully alone, but “every so often I saw a view in exceptional light, and it was so beautiful that I couldn’t bear to watch it alone. With a simple camera I recorded some of those moments so as to share an image of nature, as a sort of souvenir with friends who had no opportunity to experience it.”

But as he recalls his past impulse to escape and the desire to help others do the same, the image changes from the stills of majestic fields and mountains in the distance to a brief video of a car winding up and down a dusty, zigzag road during the dry season, resembling the time and location of Taste of Cherry. In that film, the driver sees no escape but death, but here, the plural word Roads suggests a way out. In voiceover, Kiarostami speaks of the compelling power of the road to foster continual growth. He says that the “road has always been a favorite subject for poets and writers [and that it] appears frequently in classical Persian literature, contemporary poetry, and Japanese haiku. He says that for Sepehri, the road is “exile, wind, song, travel, and restlessness,” and when he quotes one of Sepehri’s poems, the image shifts back to a wide road heading toward the mountains. The poem yearns for origins, but its path begins without a destination: “I hesitate, standing at a fork in the road. / The only way I know is the way of return. / There is no one with me on this road.”[25]

At this point the visual road becomes wide and white as it ascends and descends through dark surroundings. The music is still orchestral, but the solo horn takes the lead, corresponding to each seeker’s solo search. Once again, we sense the need for departure when the image changes to an aerial shot of a summer landscape, where the details of trees and hills are too far below to be carefully observed. The immobility of the shot and the cessation of the music precede the narrator recalling a state of depression more explicit than that of Mr. Badii in Taste of Cherry: “From the first he had borne within him a great sorrow which made him flee the company of others and kept him shut away indoors. It had been so ever since a mourner had asked him, ‘Which beautiful face does not end up buried in dust?’”

The “mourner” resembles Omar Khayyam, lamenting human insignificance in the face of death, and Kiarostami’s narrator (perhaps personal, perhaps not) is left with a heart “cold at this world” that “neither books nor degrees” can comfort. Using words, the narrator searches for the right personal, road but all he initially finds are “crisscrossed lines on a page of dust like the lines of a child’s game drawn on paper.” These may be the prosaic markings of science and philosophy that cannot offer the emotional strength that varied forms of poetry might supply.

The video of the car ascending and descending the barren hills returns, but the horn concerto also softly begins as the narrator repeats Sepehri’s search for origins in a unique synthesis of pictures, words, and music:

And at last, when he beheld the path, he saw the tale of man: that man has one road in life, running from the end to the beginning, down which he is endlessly searching for meaning, and in this boundless existence, each has his own road, sometimes endless, winding, sometimes leading nowhere, sometimes a straight line, a path leading to a garden, the shade of a tree, a spring in rocky ground.

Kiarostami then verbally concludes the film’s writing metaphor: “And man’s road, however small, flows on the page of existence, sometimes without conclusion, sometimes victorious.” In this film, the visual road to enlightenment leads up the mountain, not to a “higher” place in the sense of transcending the material body but to a place where the Creator’s writing appears on a page of pure, white snow.

After the camera cuts from the video of the car traversing the dry, zigzag road to the film’s narrative present, the ascending black road is surrounded by heavy snow. At a point where the road has narrowed to twin tire tracks, Kiarostami stops the car next to a lone dog sitting just outside the car window. The music stops, and the camera stays on the dog as we hear Kiarostami yank the brake and prepare his camera. The dog sits still just long enough for the picture. Then, having established rapport with a nonhuman form of life that many Muslims do not respect, Kiarostami emerges from the “iron cell” of his car onto a blank page of unmarred snow.

In the previously cited interview on his photography, he spoke of the way new-fallen snow produces a “uniquely pristine environment where you see no interference by human beings.” Cinematic interference also ceases as the concerto yields to the sound of wind and the cawing of crows. But the camera is careful to include Kiarostami passing a narrow, barred gate just after he gets out of the car and starts to make his way uphill through the deep drifts.

He is dressed warmly, connoting the rigor of achieving this vision that begins with a large flock of crows cawing and circling before they land on the branching filaments of a small, black tree. For a moment they are indistinguishable from the tree, but as Kiarostami approaches, they leave in a cloud of motion only to immediately return as if they were a single being. The synchronized movement of the crows and their blending with the tree confers a Taoist sense of union, but successive shots of a lone crow standing on the snow and a very young colt moving away from the camera provide the metonymy of separate lives that characterizes haiku. Similar shots include a lone horse opposite a small, dense tree; a man on horseback leading another horse; and a small black-and-white dog sitting on the snow.

Just after the crow appears, a Japanese flute begins, providing a minimalist contrast to the concerto and the elaborate language of the preceding voiceover. Meaning is created by the shaping of distinctive forms on a unified ground, and when the marks are minimal, their absolute existence can be more clearly perceived as part of the ground rather than as isolated entities. In this penultimate scene, Kiarostami translates the verbal minimalism of poetry into visual lines of small trees on snow. The horizontal lines are like Persian or Western script, while the vertical lines resemble haiku or other forms of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean writing.

Some shots convey a spiritual presence by deliberately hiding part of the visible object, recalling Sepehri’s paintings of tree trunks that leave branches and trees out of the frame to simultaneously show, as Houman Sarshar puts it, the “mystery of a unified universe” and the “boundaries of our perception.”[26] Kiarostami achieves the effect with a shot of only the bottom of a small tree trunk centered in the frame and another shot of the stump of a huge tree jutting out of the ground, also centered in the frame. But the Ahriman that threatens this cosmic concert has developed an unprecedented power to destroy.

The final sequence begins with a shot of a lone dog on a ridge, with a row of gray trees at a distance behind him, followed by a closer shot of a different breed of dog trotting toward the left. Then a sudden close-up of one of the dogs freezes into a still photograph, abruptly changing the serene tone. The dog has an alert, possibly alarmed look, and he embodies all life on earth just before a sudden blast of color rocks the frame.

The nuclear explosion lasts for twenty seconds. The dog continues to look at us as an orange flame, moving from right to left, begins to consume the screen. A thin, white, vertical line flanked by orange stripes leads the encroaching darkness on the right while greenish smoke in what remains visible erases the last of the saplings growing in the snow. As the light on the left shrinks, a prayer appears on the expanding black screen at the right: “Dear Lord, / Give us the rain from tame, / Obedient clouds / And not from dense and fiery clouds / Which summon death.” The prayer is concluded with an “Amen” and attributed to the Nahjolbalagha, a collection of sermons, letters, and narratives by Imam Ali, the son-in-law of Muhammad, a figure highly respected in all of Islam and particularly revered by Shias as second only to the prophet (see chapter 1).

But here, God may lack the omnipotence that would prevent humans from destroying his precious work. The screen continues to burn, erasing the verse, until ashes fall from the narrow edge of the photograph, now reduced to a few specks of white light. The last vestige of the collective art of God and man is the sound of crinkling paper, which lasts through the credits, until the whole screen goes black.[27]