Читать книгу Security and Suspicion - Juliana Ochs - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Senses of Security: Rebuilding Café Hillel

At 7:30 on a September morning in 2003, a middle-aged man wearing red shorts and sport sandals stood across the street from the popular Café Hillel in the German Colony, an upscale Jewish neighborhood in West Jerusalem. His head turned downward, he was reading the cover article of the daily newspaper Maʾariv, which described the previous night’s suicide bombing of this very café by a Palestinian militant. The article’s large color photograph reflected the shattered storefront he now stood opposite. In the image and before him, the café’s sign had been swept off and a blown-out roof left only a dangling black awning. Beside the man, two middle-aged women each holding a dog on a leash stood quietly facing the shell of the café from across the narrow but busy city street as they scrutinized the remains. These women soon joined three others leaning against a stone wall. As they gazed in horror, concern, and curiosity, the bystanders’ very scrutiny of the scene became part of the spectacle of the bombing.

The five women debated the order of the previous night’s events, exchanging hearsay and speaking as secondhand witnesses. “I heard that the bomber tried to get into Pizza Meter next door,” said one, “but the security guard blocked his entry, so he moved on to Café Hillel.” A second added what she had learned: “The security guard at Café Hillel tried to prevent the bomber from entering the café but was killed in the explosion.” A third woman reminded the others that the street is called Emek Refaʾim, “Valley of Ghosts.” The street’s biblical name, she implied, had augured the calamity. A mother in the group focused on the seemingly mundane details that undergirded disaster: “It was a loud explosion, but it wasn’t very big. See, the bottles on the [café’s] bar are still standing! My kids did not even wake up. Did yours?” She saw her children’s unbroken slumber as an indication of the bombing’s relatively diminutive scale, her minimization of the explosion exemplifying what Stanley Cohen calls, in his study of indifference and denial, a “dulled routinization” (Cohen 2001: 82). Reacting as if nothing had changed, or unconsciously protecting her own emotions, she readily normalized the disaster. These women were able to place the ordinary things of life, such as dogs and children, alongside a newly disjointed reality without deflating daily life itself, maintaining seemingly “orderly surfaces that deny fragmentation” (Mertz 2002: 378 n. 26).

Figure 1. Onlookers across the street from Café Hillel the morning after the bombing.

Able to speak of the attack with facility and ease, the bystanders became, as Allen Feldman did when he studied the militarized Belfast of the 1980s, “ensnared by a dialogical nexus where acts of violence had an everyday coherence and banality” (2003: 59). With numerous Palestinian suicide bombings in recent years and with marked investments of state resources and emotional energy into vigilance for Palestinian violence, when a bombing did occur, people found themselves making sense even of a sudden and dire tragedy. In the logic of daily security, bombings seemed to corroborate suspicion and substantiate hyperalertness.

Only hours before this morning assembly, the café had been a scene of chaos. At 11:30 P.M. on September 9, 2003, a Palestinian militant linked to the East Jerusalem-based Hamas group exploded himself at the entrance to Café Hillel. The large Starbucks-like café, with bold, eyecatching menu boards, trendy baristas, and vegetarian sandwiches, had opened that summer, the third branch of a successful Jerusalem chain. The bombing struck to the core of Israeli fury and fear, not only because of the ten deaths and many injuries but also because it targeted a residential area away from the city center that people saw as impervious to bombings. The suicide bombing, attributed to Hamas, came during a crumbling of the peace process. Palestinian Prime Minister Mahmoud Abbas had resigned amid a power struggle with Yasser Arafat, creating an upsurge of Palestinian violence, and Israel’s hunt for Hamas leaders entailed numerous deaths, injuries, and intensified restrictions on Palestinian movement.

During the night, as soon as those killed and wounded in the bombing had been removed from the site, and even before the last ambulance siren faded, ultra-Orthodox volunteers from ZAKA, with heavy beards, large black yarmulkes, and orange fluorescent vests, searched for and removed remaining body parts strewn throughout the site. The male-only civilian organization ensured that Jewish death rites were observed by collecting and later identifying and matching every scattered piece of flesh and drop of blood.1 Working alongside this civic religious presence were the municipal cleaning crews, who swept the window shards, hauled off splintered tables, and mopped puddles of blood. By morning, the remaining shell of the café was emptied of the fragments of disaster. Only small shards from the large glass windows that had formed the walls of the building were scattered amid the intermingled groups of rescue workers, municipal police, injured individuals, and onlookers. By the time the sun rose, the floors were clean and the tables were stacked. A peculiar kind of calm seemed to settle over the space, like the “uncanny silence” that Thomas Blom Hansen observed amid the Bombay riots (2001: 12). Though in ruins, the bombed Café Hillel was sanitized, as if a quick cleaning could prevent the bombing from becoming permanently etched into the civilian psyche.

By late morning, Emek Refaʾim Street was lined with state and civilian personnel, each group “overcoming threats to disorder” in its own way (Mehta and Chatterji 2001: 234). Television vans with cameras and journalists with microphones had been stationed since daybreak. Bulldozers carried wreckage and police directed the mounting traffic. Three tall soldiers in gray uniforms and two city police officers leaned on a parked police car, looking silently upward toward the café. Nearby, twelve male and female magavnikim, or “Border Police,” the Israeli border gendarmerie, stood between two heavy military jeeps. They wore olive-green uniforms, rifles slung over their shoulders. The role of this military presence at the café that morning was unclear: they were neither clearing the area nor inspecting passersby, but their uniforms and conspicuous weaponry nonetheless invoked the power of state sovereignty. Although the nature of the state’s authority was indistinct, performances of law and order still reified state power. As Jean and John Comaroff write in their reflection on images and perceptions of lawlessness in postcolonial South Africa, “So it is with the spectacle of policing, the staging of which strives to make actual, both to its subjects and to itself, the authorized face, and force, of the state—of a state, that is, whose legitimacy is far from unequivocal” (2004: 805). Indeed, even the quiet presence of the Israeli authorities simultaneously displayed and normalized the bombing. With a relaxed posture and muted conversation, they conveyed with uncanny reassurance that this had happened many times before and that they knew what to do. Despite its seeming passivity, the military presence enacted what Don Handelman calls in a description of Israeli emergency response the “state-owned and state-sponsored ways of remaking order from chaos” (2004: 12).2

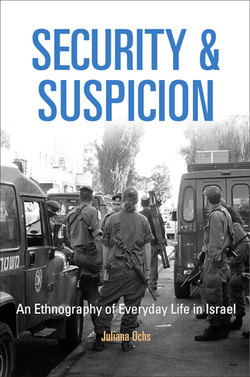

Figure 2. Near the café, Israeli Border Police cluster around their jeeps.

And yet, attempts to reclaim order at this bomb scene and even efforts to embody the state were hardly the sole task of the state. Intimate practices also permeated the site that morning. Standing next to me and staring into the bombed space was a young woman wearing a white bandana and smoking a cigarette. Next to her was a male newspaper photographer, seemingly distracted in quiet solemnity. I was tied to the site in my own way. I had been at Café Hillel the night before, sitting at a small table by the entrance and near the security guard as I waited for a fellow student from my Hebrew class to arrive. When she did, we moved inside to a seat near the back, which was her preference. After finishing our coffees, I returned home and as I crawled into bed, I heard one ambulance siren, then another, and a third. There is an intifada aphorism that one siren signals a pregnant lady, two signals a heart attack, and three a suicide bombing. A quick check online at the Haʾaretz Web site confirmed that there had been a suicide bombing—at Café Hillel. I immediately called the friend I had just met; even without family in the country, there is the impulse to call. We spoke briefly, our “what if’s felt redundant. My return to Café Hillel the next morning was as much cathartic as analytic.

The woman in the bandana, the photographer, and I stood for nearly an hour without speaking. The photographer snapped a picture every few minutes. I periodically made a note in my notebook. The woman continued to gaze and smoke. We were joined for a few moments by a middle-aged man who wore a yarmulke and carried a small prayer book, with which he prayed quietly to himself before joining us in our staring and then moving on. In this space of death, Jewish ritual was summoned and performed and Jewish objects, such as candles and prayer books, were mobilized. Two religious high school girls dressed in long denim skirts and sneakers approached next, each carrying a pocket prayer book and a cell phone, each object, presumably, a conduit for a different kind of communication. Mobile phones, in fact, dotted the landscape that day. Inside the café, an interior space even without walls, rotating groups of men spoke as much on their phones as with each other. Barking into the speaker, they negotiated with insurance companies and made plans for the rebuilding.3 Several passersby arrived at the scene only to call a friend or relative to tell them they were here, and then moved on. Some took photographs with their cell phones. Others cried into their phones; words were superfluous.

While we stared and as the neighborhood woke up and began to go to work and to school, the bombed site was first cordoned off and then enclosed. Heavy red plastic barriers replaced the red-and-white tape of the night’s temporary cordons. Behind the barrier sat male and female security guards wearing fluorescent yellow vests emblazoned with the name of their security company and the label “Security and Guarding.” By late morning, at least eight of these hired guards stood shaded by two large orange sun umbrellas advertising Straus, the ice-cream company. If the red barrier shielded daily life from a messy public space thrust into conflict, the guards, too, functioned as a kind of border. They buffered the bombed landscape with a human face that provided a security that was both commanding and compassionate.

Figure 3. A newspaper photographer and a high school girl with a prayer book and cell phone look into the shell of the café.

While a range of civilian spaces had been targets of Palestinian bombings during the second intifada, Israeli Jews tended to see cafés as the primary index of Palestinian violence. This was because Israeli aspirations toward cosmopolitanism and secularism were embodied in the country’s café culture, an ethos that selectively obscured the legacy of the Arab coffeehouse in favor of the European café (Stein 2002: 17). Bombed cafés thus stood as emblems of a precarious nation, symbols of the ways Palestinian violence transformed Israeli daily life, assaulted normative consumption, and threatened Jewish nationalism (Stein 2002). Thus when Israelis maintained that morning coffee and al fresco dining lay at the crux of conflict, they did so with little sarcasm. The normalization sought in cafés was as imperative as national order sought through pioneers’ shovels or soldiers’ guns. The idea of the normal has special resonance in Israel, a country where Jewish nationalism aimed to “normalize” the Jewish people and make them into a nation like other nations. During the second intifada, Israeli Jews in their twenties and thirties often conjured a different kind of normal, one that entailed veiling Zionism with a cosmopolitan busyness. The café culture somehow simultaneously signified this post-Zionist normal as well as the nationalist concept of Israel as a normal nation. It was not surprising, then, that the act of rebuilding and returning to a café after a bombing was, for many Israelis during the second intifada, a decisive act of normalization and perseverance.

Everything about the reconstruction of a building destroyed violently amid conflict is contested and fraught with meaning. Who does the rebuilding and where, whether it is rebuilt the same as before, whether there is an overt memorial plaque—all are open to question. Much of the literature on the rebuilding of structures ruined during war or conflict focuses on postconflict settings, contexts in which a victor has often been declared, large-scale relief work has begun, and national narratives have begun to coalesce. Nicholas Saunders’s study of the meaning contained in the landscape of the World War II Western Front, for example, shows that some landscapes of conflict are deliberately maintained in a state of destruction to serve as a testament to past aggression (2001: 42). In contrast, in the case of Israeli establishments destroyed by Palestinian bombings during the second intifada, rebuilding occurred while conflict persisted. This endowed the reconstruction efforts with significance—as modes of retaliation more than forms of memorialization, as symbols of perseverance rather than closure. Rebuilding itself became a form of participation in the conflict, tied up with discourses of violence, notions of nationhood, and strategies of security. The Israeli public expected and the state ensured the expedient renovation of bombed sites. Every café or restaurant destroyed in a suicide bombing during the second intifada was rebuilt, often in the same location. Not only the fact of rebuilding but also the process of rebuilding became routinized, with a protocol shaped by responses to prior bombings and by discourses of perseverance and swift returns to “normal.”

This chapter describes the rebuilding of Café Hillel and shows how discourses of security materialized in particular aesthetics. As the café was remade, its built forms were imbued with the politics of nationhood, and Israeli discourses of security generated their own explanations for the space’s safety and danger.4 Assertions of Israel’s strength and wellbeing sedimented themselves in the café’s walls and windows while its physical spaces and patrons’ movements through them embodied concepts of Israeli sophistication and normality. My focus on the interplay between discourse and fortified architecture follows scholars of material culture who examine translations between cultural knowledge and materiality or, as Victor Buchli explains, “the terms by which discursive empirical reality is materialized and produced” (2002: 16). In describing the rhetoric, actors, and imaginaries involved in Café Hillel’s rebuilding, this chapter introduces the ways security works in everyday life in Israel through personal rationalization, through symbols, and through cynicism, as much as through walls and certainty. Even when security takes the form of senses and signs, it generates Israeli identity and state authority.

The Public Space of a Bombing

Bombs attain a “shadowy, mysterious presence in the life of the city,” as Vyjayanthi Rao states in his ethnographic history of the 1993 bombings in Bombay and, in their immediate aftermath, constitute a particular kind of public sphere (2007: 570). Sites of suicide bombings in Israel also became instantly mythical spaces where the nation viewed itself as under threat but able to endure, spaces where conflict was simultaneously reified and normalized. After its September bombing, Café Hillel reentered the public domain as a national, state, and religious site, a process mediated by artifacts, practices, and discourses of security.5 The site was consecrated by religious practices, whether in the form of ZAKA’s work or individual prayer, and by performances of security. Security introduced feelings of nationalism not through force or formal pronouncement but through subtle inflections of ritual and sociality.

Hired by Café Hillel from a private security company and directed by the Jerusalem police, six security guards lined the inside of Café Hillel’s red barrier on the first morning of rebuilding. I asked one vested worker why there were so many guards. He explained, in a voice suggesting I should have already known, that bombed sites are immediately bolstered following an attack for fear that a second bombing will strike soon after. As I observed in the ensuing hours, however, the guards’ role was not just preemptive; their function was undoubtedly social. The security guards kept the pedestrian public at a safe distance from the site to enable the clean-up crews and insurance appraisers to do their work. More than keeping danger and intrusion from the barricaded area, they worked to prevent the terror and tragedy from seeping into a busy Israeli workday. The guards were attentive to their own comportment and monitored that of their coworkers. Amid a mid-morning mix-up regarding the placement of the barrier, one guard commanded another: “Don’t yell. Speak quietly,” suggesting their attention to calm. The guards were conscientious about their role in projecting to the many passersby that the situation was under control and that official bodies were efficiently restoring order to the street and to daily life.

In many ways, the post-bombing scene exemplified what Baruch Kimmerling has called an “interrupted system” to describe how Israeli society can fluidly mobilize military and civilian domains during times of intensified conflict without allowing war to transgress the boundaries of ordinary life. Kimmerling focused on the sinuous transitions Israeli society is able to make between a “time of interference” and “routine time,” although at the Café Hillel site, the emergency was so routinized that calamity could have easily been mistaken for routine (1985: 11). An hour after I arrived, workers surrounded the damaged café with a tall metal frame overlaid with light-blue wooden panels, which shielded the building from view. In the coming weeks, this wall, like the security guards, not only enclosed the café as it was rebuilt but enabled the bombed space to become fleetingly a nonplace, an ambivalent space temporarily removed from the realm of the familiar (Augé 1995: 78). As the café underwent restoration and reconstitution, it became a space out of time that pedestrians perceived only partially and in fractions, even as it was a public space fully entrenched in the ongoing political conflict.

The red barricades concealed but also drew attention to the disorder that morning. Bystanders congregated and security guards worked to move the mass of people across the street. By this point, the woman in the white bandana sat on the ground, her teary face in her hands. The photographer, worn out, leaned against a wall. I, emotionally exhausted, was in tears as well. The guard must have noticed the emotion of the three of us who had been there all morning, and when he cordoned off the site, he quietly let us remain behind the barricade. He seemed as attentive to our emotional needs as to the need for social order, or perhaps he recognized that those needs were inseparable. In this way, he acted like the Parisian Metro police that Patricia Paperman describes, who were experts in social emotion, discerning affect “in subtleties of social interaction” (2003: 399). The security that the private café guards provided when they calmly answered questions, when they erected barriers, and when they cordoned off people was a security more sensitive and considerably less tangible than one might expect from armed guards at the site of a Palestinian suicide bombing.

Figure 4. A woman from the neighborhood lights memorial candles.

Artifacts of memorialization immediately filled the site. In the hours after the bombing, almost as soon as bodies had been carried away, people began to fill the concrete railing adjacent to the café with traditional Jewish memorial (yahrtzeit) candles in blue tin holders. When candles blew out in the wind, new visitors rekindled their flames. Over the course of the next day, the entire wall overflowed with candles and discarded matches. Soon, the floor beneath the wall and, later, a table set up specially, was studded with more candles as well as with flowers, small notes, and prayer books left for others to use. The bombing space became not only highly charged but also sacralized. Soon, a large Israeli flag hoisted by neighborhood residents flew from the security guard stand. The blue-and-white flag fluttering in the wind seemed to avow that rebuilding was a national duty.

In the weeks of rebuilding, the assemblage of ad hoc memorial artifacts developed more permanence. The pale-blue wall concealing construction became a backdrop for traditional Jewish Israeli bereavement-announcements mounted by family members. Printed in stark black letters, they publicized the name of the deceased, provided information about the funeral and house of mourning, and sometimes contained an inscription or biblical verse. Large colored photographs and smaller black-and-white newspaper clippings were mounted on the wall. Soon, two small tables were set up to hold large floral wreaths, some with the names of national and international charitable and political organizations, and others with individuals’ names handwritten on ribbons. These stood for days, until they withered and were replaced by new wreaths. Care for these mounted objects was the impromptu duty of the security guards, who hung up photographs given to them by visitors, taped on personal blessings, and kept the candles near the wreaths lit. These guards, employees of a security company contracted by Café Hillel and paid by the hour, were the custodians not only of the café and the crowds but also of a community’s mourning. Their “security” was far reaching, sensitive to emotions, and visibly relational.

Figure 5. A security guard sits inside the red barricade, chatting with a passerby. On the temporary blue wall behind him hang memorial posters and floral wreaths.

The Aesthetics of Security

With workers on ladders still adding final touches, Café Hillel reopened exactly one month after the bombing, the timing linked significantly to the end of shloshim, the traditional thirty-day Jewish mourning period. At a quiet but well-attended memorial ceremony, participants lit candles and a Jerusalem rabbi mounted a mezuzah, an entryway amulet containing passages from scripture. In the café the next morning, a steady trickle of patrons entered, resuming their routine, this time in a distinctively politicized space. As one customer explained to me that day, “You want to show some solidarity. Because you identify yourself with the place, with the losses. Because you’re thinking about what happened there, about all the people that got killed and injured, about the people that you’ve read about in the papers.” For some, sitting in the café now had a valence of patriotic defiance, seen as unwillingness to give in to Palestinian violence and its efforts to disrupt daily life.

As I observed time and again, people who entered the reopened café lingered by the doorway to survey the new space before proceeding to the counter. They scanned the entirety of the space, seeming to look as much from curiosity as from concern. Was the café rebuilt as before? Was it safer now? Many patrons ordered their coffee to take out, something considerably more common after the bombing. People who sat down with their coffee tended to sit along the back wall, a common safety-minded practice of positioning oneself as far as possible from the potential entry-point of a suicide bomber. Israelis sometimes used the term omek estrategi, “strategic depth,” which in military terminology refers to the distance between the front lines and key inner population centers. In specifically Israeli military discourse, there is the idea that Israel must attack Palestinians first to ensure that military activities take place on enemy territory, something that Ariel Sharon long advocated. When the concept was transplanted to civilian urban space, the doorway to a downtown Jerusalem café becomes the buffer zone and the space outside that, enemy territory. There was always a combination of cynical humor and gravity when people used “strategic depth” to describe where they wanted to sit. They recognized the absurdity of their depiction of cafés as war zones, but they still really experienced public spaces as zones of lurking threat and everyday risk calculation. It was as Allen Feldman wrote about the polarity between the observer and the observed: “that relations of domination are spatially marked by the increase of perceptual (and thus social) distance from the body of the Other” (1994: 92).

Perhaps the gawking patrons noticed what I had observed: that the café appeared much the same as it had before the bombing. The newly rebuilt Café Hillel was fronted, as it had been before, with large plate-glass windows lined inside with a long wooden bar and a row of stools. Adjacent to the cashiers’ counter, a glass display case of cakes and sandwiches still greeted patrons upon entering and small round tables still stood in the large indoor space. But what had been a large outdoor seating area was now enclosed like a greenhouse with tall glass windows. The enclosure seemed to stand as a shield against future bombings, yet with its planked wooden floors and a black cloth awning overhead, it retained an outdoor feel and did not revise the atmosphere of the café as a whole. Why was the café rebuilt so similarly to its pre-bombing form? One would have thought that the café’s owners, not to mention its patrons, would want the café to feel more fortified, to be enclosed in brick, perhaps, instead of defenseless glass. But the politics of rebuilding during conflict combined with the psychology of security to create a unique set of aesthetic values.

During the height of the second intifada, in 2002 and 2003, it was generally only venues with security guards that could attract enough patrons to remain open, but only successful venues were able to afford guards in the first place. Cafés and restaurants around the country were responsible for hiring and paying for their own security guards. Similarly, as systematic and state-driven as post-bombing reconstruction appeared, the owners of bombed commercial venues were largely accountable for the completion, though not the entire cost, of rebuilding. Although the state, generally in the form of the local municipal police, gave case-specific guidelines for rebuilding with increased fortification, the implementation of those guidelines and the course of the place’s securitization was a collaborative process.